Specialization, Productivity, and the Division of Knowledge

Simple trades of the kind found on eBay create value, but the true power of trade is discovered only when people take the next step, specialization. In a world without trade, no one can afford to specialize. People will specialize in the production of a single good only when they are confident that they will be able to trade that good for the many other goods that they want and need. Thus, as trade develops, so does specialization, and specialization turns out to vastly increase productivity.

How long could you survive if you had to grow your own food? Probably not very long. Yet most of us can earn enough money in a single day spent doing something other than farming to buy more food than we could grow in a year. Why can we get so much more food through trade than through personal production? The reason is that specialization greatly increases productivity. Farmers, for example, have two immense advantages in producing food compared to economics professors or students: Because they specialize, they know more about farming than other people, and because they sell large quantities, they can afford to buy large-scale farming machines. What is true for farming is true for just about every field of production—specialization increases productivity. Without specialization and trade, we would each have to produce our own food as well as other goods, and the result would be mass starvation and the collapse of civilization.

The human brain is limited and there is much to know. Thus, it makes sense to divide knowledge across many brains and then trade. In a primitive agricultural economy in which each person or household farms for themselves, each person has about the same knowledge as the person next door. In this case, the combined knowledge of a society of 1 million people barely exceeds that of a single person.1 A society run with the knowledge of one brain is a poor and miserable society.

In a modern economy, many millions of times more knowledge is used than could exist in a single brain. In the United States, for example, we don’t just have doctors—we have neurologists, cardiologists, gastroenterologists, gynecologists, and urologists, to name just a few of the many specializations in medicine. Knowledge increases productivity so specialization increases total output. All of this knowledge is possible, however, only because each person can specialize in the production of one good and then trade for all other desired goods. Without trade, specialization is impossible.

The extent of specialization in a modern economy explains why no one knows the full details of how even the simplest product is produced. A Valentine’s Day rose may have been grown in Kenya, flown to Amsterdam on a refrigerated airplane, and trucked to Topeka by drivers staying awake with Colombian coffee. Each person in this process knows only a small part of the whole, but with trade and market coordination, they each do their part and the rose is delivered without anyone needing to understand the whole process.

The extent of specialization in modern society is remarkable. We have already mentioned the many specializations in medicine. We also have dog walkers, closet organizers, and manicurists. It’s common to dismiss the latter jobs as frivolous, but trade connects all markets. It’s the dog walkers, closet organizers, and manicurists who give the otolaryngologists—specialists in the nose, ear, and throat—the time they need to perfect their skills.

The division of knowledge increases with specialization and trade. Economic growth in the modern era is primarily due to the creation of new knowledge. Thus, one of the most momentous turning points in the division of knowledge happens when trade is extensive enough to support large numbers of scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs, all of whom specialize in producing new knowledge.

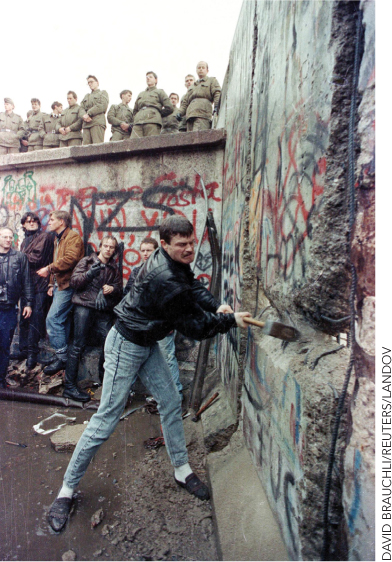

Every increase in world trade is an opportunity to increase the division of knowledge and extend the power of the human mind. During the Communist era, for example, China was like an island cut off from the world economy: 1 billion people who neither traded many goods nor many ideas with the rest of the world. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the opening to the world economy of China, Russia, Eastern Europe, and other nations greatly adds to the productive stock of scientists and engineers and is one of the most promising signs for the future of the world. Billions of minds have been added to the division of knowledge and cooperation around the world has been extended further than ever before.

Consider the many ideas and innovations that make life better, from antibiotics, to high-yield, disease-resistant wheat, to the semiconductor. Insofar as those goods have originated in one place and then been spread around the world, improving the lives of millions or billions, it is because of trade.