Speculation

Speculation is the attempt to profit from future price changes.

Suppose that you expect that a war in the Middle East is likely next year and that, if it should occur, the supply of oil will decrease, thereby pushing up the price of oil. How could you profit from your expectation? The way to make money is to buy low and sell high, so you should buy oil today when the price is low, hold the oil in storage, and then sell it next year after war breaks out, when the price is higher. Figure 7.2 shows this process, which is called speculation. We have used vertical supply curves, meaning that the amount of oil is fixed, to simplify the diagram.

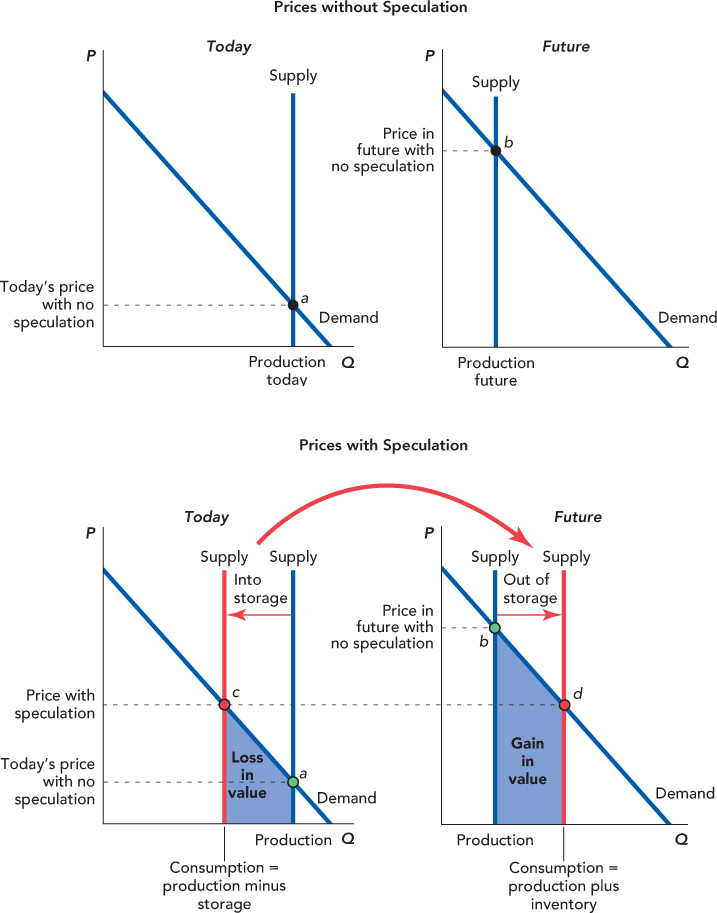

FIGURE 7.2

The bottom panel shows what happens with speculation. In the left panel, oil speculators buy oil and put it into storage, pushing up the price of oil and reducing consumption today—thus, the equilibrium shifts from point a to point c. In the future when the price of oil is high (at point b), speculators sell their oil from storage. The oil flowing out of storage pushes the price down and allows people to consume more oil even though production is low.

The value of oil to consumers (in blue) falls today when oil is put into storage, but rises by an even larger amount in the future when oil is in short supply and speculators move their stocks out of storage.

The top panel shows what happens without speculation. Production today is high and today’s price is low (point a). Future production, however, will be disrupted by the war, pushing up the future price (point b). Notice that without speculation, the war disrupts the oil market and prices jump from point a to point b.

The bottom panel shows what happens with speculation. Speculators buy oil today and they put it into storage—this reduces the quantity available for consumption today and pushes up today’s price (point c). Next year, however, when the war occurs, production is low but consumption is higher than it would have been without speculation and prices are lower because the speculators sell oil from their inventories (point d). Notice that with speculation, preparations are made for any disruption in oil production and oil prices are smoothed.

Speculators raise prices today but lower prices in the future. As a result, speculators have an image problem because the media often report when speculators raise prices but rarely do they report when speculators lower prices. Overall, however, society is better off from speculation because speculators move oil from when it has low value (today) and move it to when it has high value (the future). When producers put oil in storage, society doesn’t get to consume that oil so some wants become unsatisfied—the loss in value from these unsatisfied wants is measured by the blue area in the (bottom) left panel of Figure 7.2 (once again, the value of the good in its various uses is measured by the height of the demand curve). But when the speculators sell that oil in the future, consumption increases—more wants are satisfied—and the value of this increase in consumption is measured by the much larger blue area in the right panel. Thus, when speculators are right, they move oil from today, where it has low value, to the future, where the value of oil is much higher—in the process making society better off.

Speculators, of course, don’t always guess correctly. But speculators put their money where their mouth is. They have strong incentives to be as accurate as possible because when they are wrong, they lose money—a lot of money. Bad speculators soon find themselves out of a job. Anyone who is able to be a speculator for a long time is either very, very lucky or just very good. So, on net, speculators tend to make prices more informative, even though in particular instances many speculators are wrong.

A careful observer of Middle East politics might have very good information about the probability of war in the Middle East but have no easy way to store oil. Fortunately, the market provides a way to speculate in oil without building oil tanks in your backyard.

Futures are standardized contracts to buy or sell specified quantities of a commodity or financial instrument at a specified price with delivery set at a specified time in the future.

A speculator can buy oil futures. Oil futures are contracts to buy or sell a given quantity of oil at a specified price with delivery set at a specified time and place in the future. On the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX), you can buy futures for light, sweet crude oil to be delivered in Cushing, Oklahoma, at 30, 36, 48, 72, or 84 months in the future at a price agreed on today. What makes futures contracts important is that despite specifying delivery and acceptance in Cushing, almost all futures contracts actually settle in cash.

Let’s see how this works. Suppose Tyler believes that the price of oil will be higher in the future than what other people are expecting. Tyler buys an oil contract that gives him the right to 1,000 barrels of oil to be delivered (in Cushing) 30 months in the future. Tyler agrees that on delivery he will pay the seller, Alex, $50 per barrel or $50,000. Similarly, Alex has agreed to deliver 1,000 barrels of oil in Cushing in 30 months. Thirty months from now, Tyler’s expectation is proven correct—the actual or “spot” price of oil is $82. If Tyler went to Cushing, he could physically accept the oil from Alex, give him $50,000 and then turn around and sell the oil to someone else for $82 per barrel for a profit of $32 per barrel or $32,000. Instead of doing that, however, Tyler and Alex could agree to cash settlement. Alex has agreed to give Tyler 1,000 barrels of oil, which are currently worth $82,000, for a price of $50,000. Instead of giving Tyler the oil, suppose that Alex gives Tyler the cash difference, $32,000, and they call it even. The advantage of cash settlement is that Tyler and Alex can both speculate on the price of oil without ever accepting or delivering oil. Moreover, neither Tyler nor Alex ever have to go to Cushing, which is sadly lacking in good ethnic restaurants.*

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 7.7

Speculation occurs in stocks as well as commodities. In 2008, Lehman Brothers, a Wall Street investment banking firm, complained that speculators were driving the price of its stock lower and lower. During this time, Lehman continued to give rosy forecasts. Later in 2008, Lehman Brothers went bankrupt. Why was the forecast of the speculators more informative on net than the statements being issued from Lehman?

Speculation occurs in stocks as well as commodities. In 2008, Lehman Brothers, a Wall Street investment banking firm, complained that speculators were driving the price of its stock lower and lower. During this time, Lehman continued to give rosy forecasts. Later in 2008, Lehman Brothers went bankrupt. Why was the forecast of the speculators more informative on net than the statements being issued from Lehman?

Futures markets are used not only for speculation but also for reducing risk. An airline that wants to know in advance what its fuel costs are going to be next year can lock in the price by buying oil on the futures market. Instead of buying futures, farmers can sell futures. A soybean farmer plants the crop today but does not harvest it until next year when the soybean price could be quite different from today’s spot price. To avoid the price risk, the farmer can sell futures, that is, agree to sell so many soybeans at harvest time at a price agreed on today. Futures markets are also common in currencies. Suppose that Ford expects to sell 1,000 cars in Germany for 25,000 euros each. At the end of the year, how many dollars will Ford make? Ford doesn’t know because the euro/dollar exchange rate can fluctuate. By selling euro futures, Ford can lock in the exchange rate.