Rent Controls (Optional Section)

A rent control is a price ceiling on rental housing.

A rent control is a price ceiling on rental housing, such as apartments, so everything we have learned about price ceilings also applies to rent controls. Rent controls create shortages, reduce quality, create wasteful lines and increase the costs of search, cause a loss of gains from trade, and misallocate resources.

Shortages

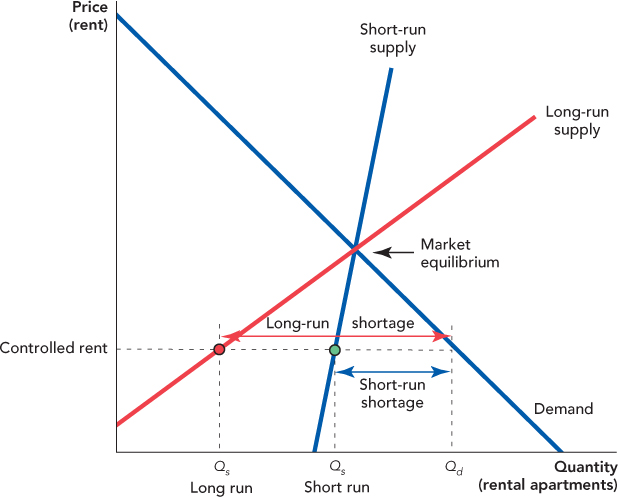

Rent controls usually begin with a “rent freeze,” which prohibits landlords from raising rents. Since rent controls are often put into place when rents are rising, the situation quickly comes to look like Figure 8.8, with the controlled rent below the market equilibrium rent.

FIGURE 8.8

Apartments are long-lasting goods that cannot be moved, so when rent controls are first imposed, owners of apartment buildings have few alternatives but to absorb the lower price. In other words, the short-run supply curve for apartments is inelastic. Thus, Figure 8.8 shows that even though the rent freeze may result in rents well below the market equilibrium level, there is only a small reduction in the quantity supplied in the short run.

In the long run, however, fewer new apartment units are built and older units are turned into condominiums or torn down to make way for parking garages or other higher-paying ventures. Thus, the long-run supply curve is much more elastic than the short-run supply curve, and the shortage grows over time from the short-run shortage to the long-run shortage.

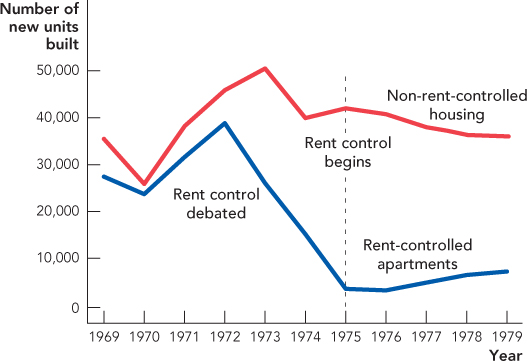

Although old apartment buildings can’t disappear overnight, future apartment buildings can. Developers look for profits over a 30-year or longer time frame, so even a modest rent control can sharply reduce the value of new apartment construction. Developers who fear that rent controls are likely will immediately end their plans to build. In the early 1970s, for example, rent control was debated in Ontario, Canada, and put into place in 1975. In the five years before controls were put into place, developers built an average of 27,999 new apartments per year. In the five years after controls were put into place, developers built only 5,512 apartments per year. Figure 8.9 graphs the number of new apartment starts and the number of new house starts per year from 1969 to 1979. The sharp drop in new apartment construction in the years when rent controls first started to be debated is obvious. But perhaps the drop was due to other factors like the state of the economy. To test for this possibility, we also graph the number of new houses that were built annually during this time. The demand for houses and the demand for apartments respond similarly to the economy, but price controls on houses were never debated or imposed. We can see from Figure 8.9 that prior to 1972 the number of new apartment starts was similar to the number of new house starts. But when rent control became a possibility, apartment construction fell but the construction of houses did not. Thus, it’s likely that rent control and not the general state of the economy (which would also have affected house starts) was responsible for the sharp drop in the number of new apartments built.

FIGURE 8.9

Reductions in Product Quality

Rent controls also reduce housing quality, especially the quality of low-end apartments. When the price of apartments is forced down, owners attempt to stave off losses by cutting their costs. With rent controls, for example, owners mow the lawns less often, replace lightbulbs more slowly, and don’t fix the ele vators so quickly. When the controls are strong, cheap but serviceable apartment buildings turn into slums and then slums turn into abandoned and hollowed-out apartment blocks. In Manhattan, for example, 18% of the rent-controlled housing is “dilapidated or deteriorating,” a much higher percentage than in the uncontrolled sector.10 Rent controls in European countries have tended to be more restrictive than in the United States, leading the economist Assar Lindbeck to remark, “Rent control is the most effective method we know for destroying a city, except for bombing it.”11 Lindbeck, however, was wrong, at least according to Vietnam’s foreign minister who in 1989 said, “The Americans couldn’t destroy Hanoi, but we have destroyed our city by very low rents.”12

Wasteful Lines, Search Costs, and Lost Gains from Trade

Lines for apartments are not as obvious as for gasoline, but finding an apartment in a city with extensive rent controls usually involves a costly search. New Yorkers have developed a number of tricks to help them, as Billy Crystal explained in the movie When Harry Met Sally:

What you do is, you read the obituary column. Yeah, you find out who died, and go to the building and then you tip the doorman. What they can do to make it easier is to combine the obituaries with the real estate section. Say, then you’d have “Mr. Klein died today leaving a wife, two children, and a spacious three-bedroom apartment with a wood-burning fireplace.”

Search can be especially costly for people who landlords think are not “ideal renters.” At the controlled price, landlords have more customers than they have apartments, so they can pick and choose among prospective renters. Landlords prefer to rent to people who are seen as being more likely to pay the rent on time and not cause trouble for other tenants, for example, older, richer couples without children or dogs. Landlords might also discriminate on racial or other grounds. Indeed, a landlord who doesn’t like your looks can turn you down and immediately rent to the next person in line. Landlords can discriminate even if there are no rent controls, but without rent controls, the vacancy rate will be higher because the quantity of apartments will be larger and turnover will be more common, so landlords who turn down prospective renters will lose money as they wait for their ideal renter. Rent controls reduce the price of discrimination, so remember the law of demand: When the price of discrimination falls, the quantity of discrimination demanded will increase.

Bribing the landlord or apartment manager to get a rent-controlled apartment is also common. Bribes are illegal but they can be disguised. An apartment might rent for $500 a month but come with $5,000 worth of “furniture.” Renters refer to these kinds of tie-in sales as paying “key money,” as in the rent is $500 a month but the key costs extra. Nora Ephron, the screenwriter for When Harry Met Sally, lived for many years in a five-bedroom luxury apartment that thanks to rent control cost her just $1,500 a month. She did, however, have to pay $24,000 in key money to get the previous renter to move out!

The analysis of lost gains from trade from rent controls is exactly the same as we showed in Figure 8.3 for price controls on gasoline. At the quantity supplied under rent control, demanders are willing to pay more for an apartment than sellers would require to rent the apartment. If buyers and sellers were free to trade, they could both be better off, but under rent control, these mutually profitable trades are illegal and the benefits do not occur.

Misallocation of Resources

As with gasoline, apartments under rent control are allocated haphazardly—some people with a high willingness to pay can’t buy as much housing as they want, even as others with a low willingness to pay consume more housing than they would purchase at the market rate. The classic example is the older couple who stay in their large rent-controlled apartment even after their children have moved out. It’s a great deal for the older couple, but not so good for the young couple with children who as a result are stuck in a cramped apartment with nowhere to go.

Economists can estimate the amount of misallocation by comparing the types of apartments that renters choose in cities like New York, which has had rent controls since they were imposed as a “temporary” measure in World War II, with the types of apartments that people choose in cities like Chicago, which has a free market in rental housing. In one recent study of this kind, Edward Glaeser and Erzo Luttmer found that as many as 21% of the renters in New York City live in an apartment that has more or fewer rooms than they would choose if they lived in a city without rent controls.13 This misallocation of resources creates significant waste and hardship.

Rent Regulation

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 8.3

If landlords under rent control have an incentive to do only the minimum upkeep, what inevitably must accompany rent control? Think of a tenant with a dripping faucet: How does it get fixed?

If landlords under rent control have an incentive to do only the minimum upkeep, what inevitably must accompany rent control? Think of a tenant with a dripping faucet: How does it get fixed?

Question 8.4

New York City has had rent control for decades. Assume you are appointed to the mayor’s housing commission and convince your commission members that rent control has been a bad thing for New York. How would you get rid of rent control, considering the vested interests?

New York City has had rent control for decades. Assume you are appointed to the mayor’s housing commission and convince your commission members that rent control has been a bad thing for New York. How would you get rid of rent control, considering the vested interests?

In the 1990s, many American cities with rent control changed policy and began to eliminate or ease rent controls. Some economists refer to these new policies not as rent control but as “rent regulation.” A typical rent regulation limits price increases without limiting prices. Price increases, for example, might be limited to, say, 10% per year. Thus, rent regulations can protect tenants from sharp increases in rent, while still allowing prices to rise or fall over several years in response to market forces. Rent regulation laws usually also allow landlords to pass along cost increases so the incentive to cut back on maintenance is reduced. Economists are almost universally opposed to rent controls but some economists think that moderate rent regulation could have some benefits.14