THE RELATIVITY THEORIES

12-11 Einstein revolutionized our understanding of space, time, and gravity

It seems reasonable that if I watch you traveling at, say, 100 km/h (about 60 mi/h), my measurements of your mass, the rate at which your watch runs, and the length of your car would be the same as the measurements you make of these things. In fact, none of these measurements would be the same. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Einstein began a revolution in science by disregarding his common sense, making a few physical assumptions about nature, and using mathematics to explore their consequences. The resulting equations revealed profound, albeit highly counterintuitive, insights into how nature works. Armed with the equations that Einstein derived, scientists have been exploring and using the consequences of his theories to develop new technology and a deeper understanding of how matter, energy, space, and time interact.

Special relativity changes our conception of space and timeIn 1905, Albert Einstein derived his theory of special relativity, a description of how motion affects our measurements of distance, time, energy, and mass. He was guided by two assumptions. Although the implications of the theory proved revolutionary, the first notion seems simple:

Your description of physical reality is the same regardless of the (constant) velocity at which you move.

In other words, as long as you are moving in a straight line at a constant speed, you experience the same laws of physics as anyone else moving at any other constant speed in a straight line and in any other direction. To illustrate this first idea, suppose you were inside a closed boxcar moving smoothly in a straight line at 100 km/hr (62 mi/hr) and you dropped a pen from a height of 2 m (6.6 ft). You time how long it takes the pen to reach the floor (about 0.64 second). Then the train is stopped and you repeat the same experiment in the station. The time it would take the pen to fall would be identical.

The second idea seems more bizarre:

Regardless of your speed or direction, you always measure the speed of light to be the same.

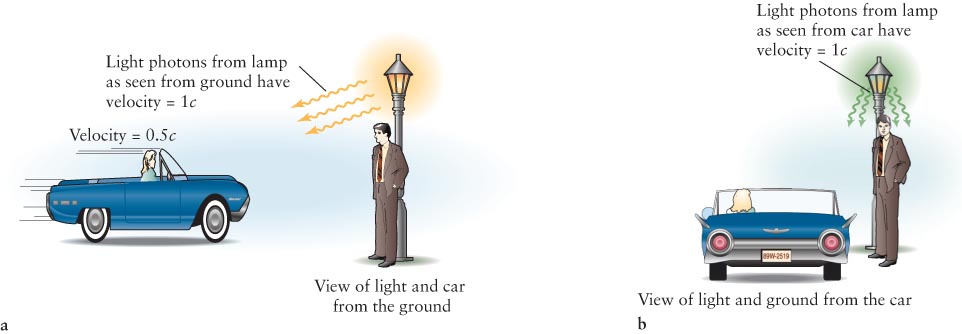

Suppose that you are in a (very powerful) car moving toward a distant street lamp at 150,000 km/s (93,000 mi/s). In simpler terms, this is 50% of the speed of light, denoted 0.5c (Figure 12-28a). A friend of yours leaning on the lamppost sees you coming and also sees light from the lamp heading toward you at c. How fast do you see the photons of light coming at you? It would seem reasonable that you clock them at c + 0.5c, which is the speed of the photons toward you plus your speed toward them, but this is incorrect. You will, in fact, see the photons coming toward you with the same speed, c, that your friend sees them leaving the lamp (Figure 12-

Einstein’s theory of special relativity expresses these two assumptions mathematically, and the results of these assumptions have been confirmed in innumerable experiments. Perhaps the most well-

Three other fundamental results of special relativity also defy our everyday experience:

Focus Question 12-13

How much mass, m, would have to be destroyed to create an amount of energy, E?

370

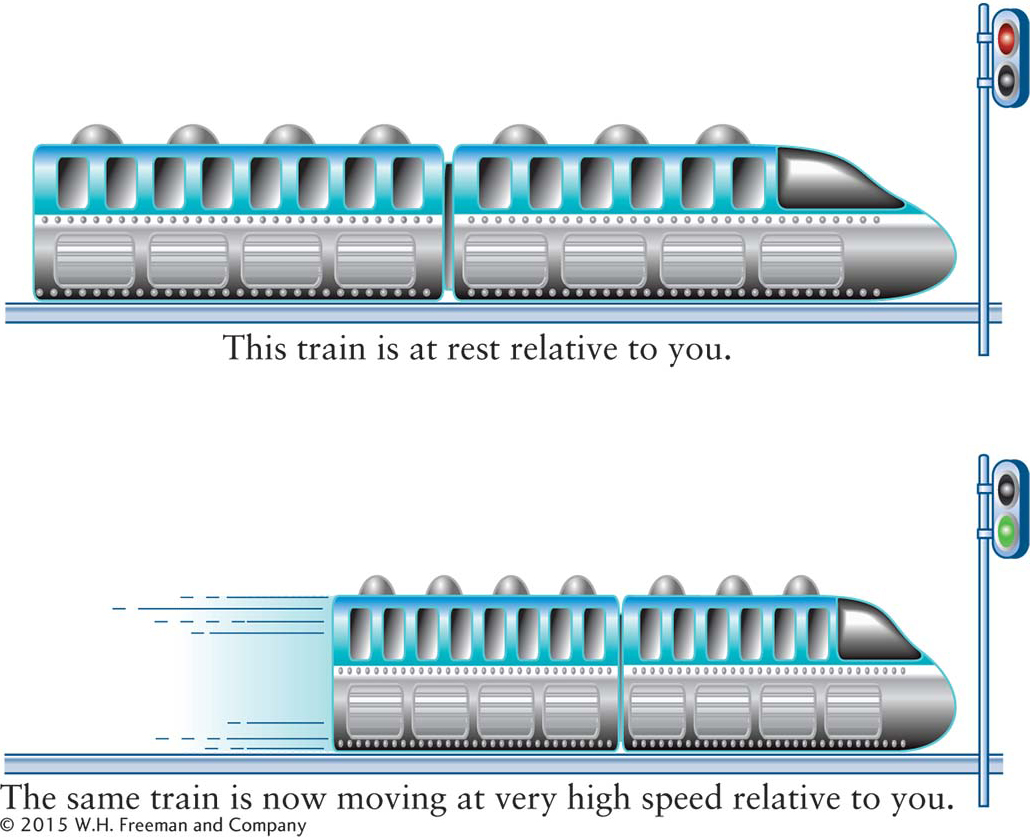

The length of an object decreases as its speed increases. In other words, if a train moves toward or away from you, you would measure its length to be shorter than you would measure its length to be when it is stopped at the station (Figure 12-29). (This result also explains why the car in Figure 12-

28a appears too short.) This result is called length contraction. However, if you measure the length of the moving train while you are moving with it, your measurement of its length will be the same as you measured on the ground when it was at rest. The word relativity emphasizes the importance of the relative speed between the observer and the measured object.  Figure 12-29 Movement and Space According to the theory of special relativity, the faster an object moves, the shorter it becomes in its direction of motion as observed by someone not moving with the object. It becomes infinitesimally short as its speed approaches the speed of light. The dimensions perpendicular to the object’s motion are unchanged.

Figure 12-29 Movement and Space According to the theory of special relativity, the faster an object moves, the shorter it becomes in its direction of motion as observed by someone not moving with the object. It becomes infinitesimally short as its speed approaches the speed of light. The dimensions perpendicular to the object’s motion are unchanged.Clocks that you see as moving run more slowly than do clocks you see at rest. This result is called time dilation. Indeed, the faster a clock moves relative to you, the slower it appears to tick from your perspective. For example, air travelers actually age more slowly than they would if they did not fly (although because of the relatively low speeds of aircraft travel compared to the speed of light, this difference is imperceptibly small). People flying in aircraft do not feel time passing more slowly, however, because their biological activities slow down at the same rate as the clocks around them. Only an observer moving relative to an airplane sees that the clock and the activities of the high-

speed travelers aboard the plane have slowed. These connections between motion and clocks mean that space and time cannot be considered as two separate concepts. Relativity requires us to combine them in a single entity, thus creating the concept of spacetime. 371

The mass of an object increases as it moves faster. The concept of mass is discussed in Sections 2-

5 and 2- 7. The equations of special relativity reveal that an object moving at the speed of light would have an infinite amount of mass. It is impossible for any object with mass to reach this speed, much less go faster than the speed of light, because an infinite amount of mass is more than the total mass that exists in the universe. Furthermore, the equation F = ma (F is the force exerted on an object, m is its mass, and a is the acceleration it undergoes; see Section 2- 7 ) reveals that if an object’s mass is infinite, the force necessary to accelerate this object must also be infinite. Because the total force available to move matter in the universe is finite, no massive object can be sped up to the speed of light: The speed of light is the universal speed limit.

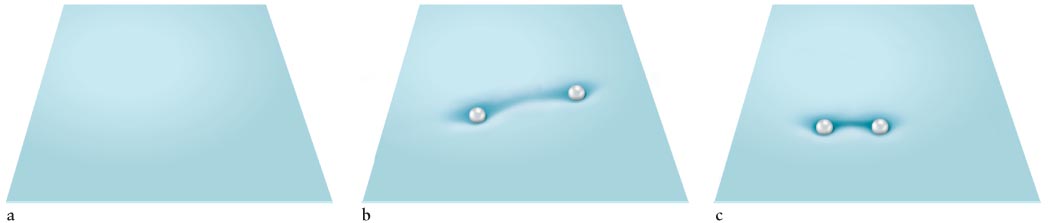

General relativity explains how matter warps spacetime, creating gravitational attractionWhile special relativity tells us how the mass of an object is related to its (constant) speed, this theory is special (in the sense of limited) because it does not account for the effects of acceleration and gravitation. These effects were incorporated by Einstein in 1915 into a more general theory, called the theory of general relativity (or, more simply, general relativity). It describes how spacetime changes shape in the presence of matter (Figure 12-30): the greater the mass, the more the distortion or curvature. Furthermore, the curvature of spacetime creates attraction between all pieces of matter in the universe (Figure 12-

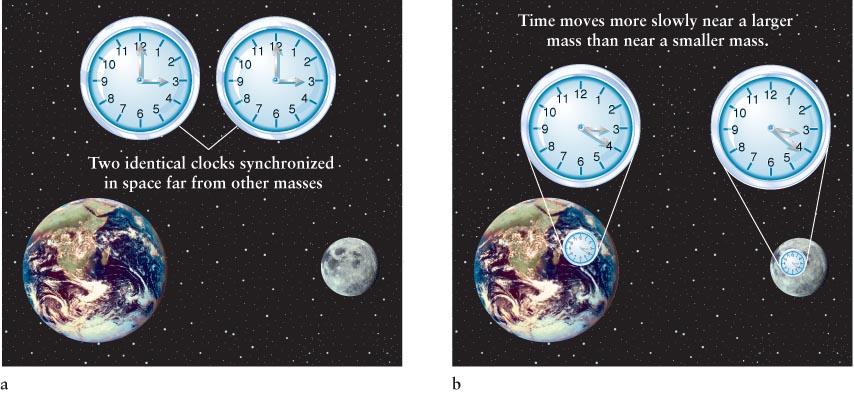

Another result of general relativity is that time slows down in the presence of matter. The greater the concentration of matter, the slower clocks tick (Figure 12-31). For example, time passes more slowly for us here on Earth’s surface than it would for astronauts on the Moon, which has less mass than Earth. Our technology has become so sophisticated that the slowing of time due to both relative speed, as discussed earlier in this chapter, and slowing due to the presence of nearby matter, as shown in Figure 12-

General relativity predicts more accurately the motion and other behaviors of matter than do Newton’s laws of motion and his law of gravitation. Newton’s laws are accurate only for objects with relatively small masses, slow velocities compared to the speed of light, and low densities (such as those for objects found on Earth). Newton’s laws are also limited to motion sufficiently far from large masses (such as the Sun) or high-

Focus Question 12-14

What property of matter does general relativity address that is not included in special relativity?

372

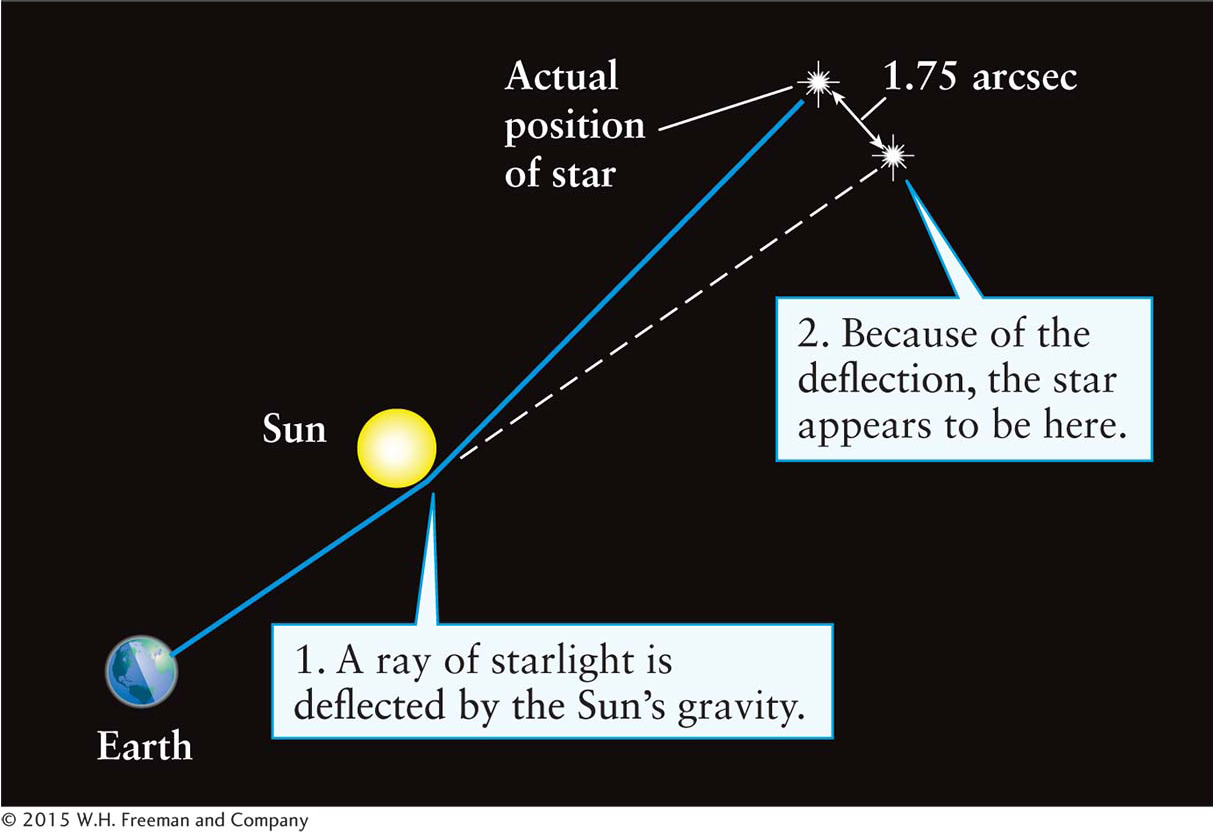

Spacetime affects the behavior of lightBesides affecting the behavior of objects, the curvature of spacetime changes the path and wavelength of light that passes near any matter. (These behaviors are not predicted by Newton’s laws.) Light travels along trajectories in space called geodesics. You can get an idea of how geodesics work by imagining that you are flying on the shortest possible route from one city to another. Your path would be analogous to a geodesic for a photon, and like that particle in the presence of matter in space, you would actually be following the curve of Earth’s surface, rather than going in a “straight line.” The first experimental verification of general relativity, made in 1919 during a solar eclipse, was its prediction that geodesics are sufficiently curved by the mass of the Sun to cause light from stars passing nearby to arc around it (Figure 12-32).

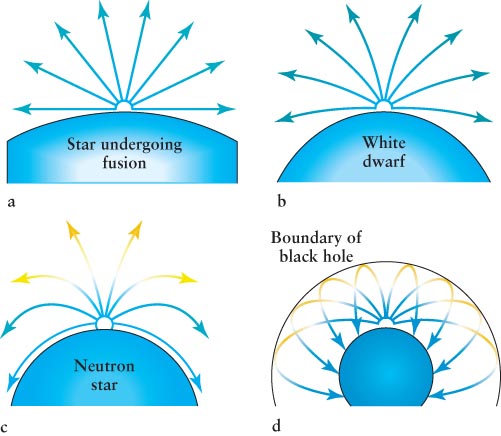

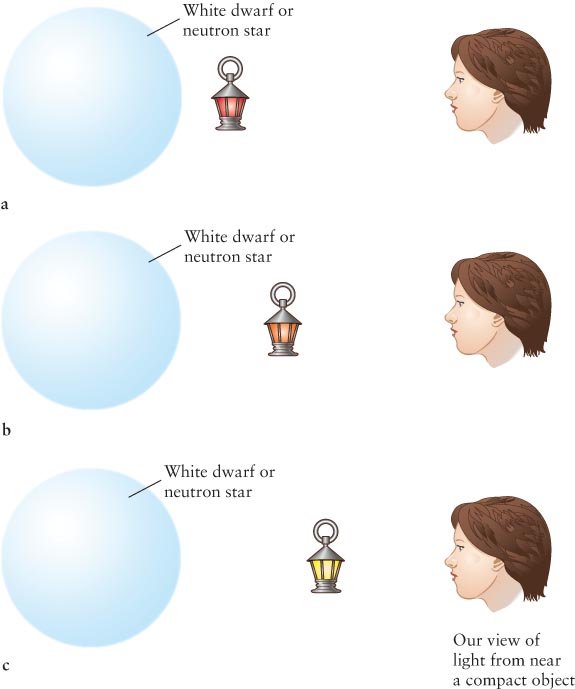

Photons that leave the vicinity of a star also lose energy in climbing out of the star’s gravitational field. They do not slow down like a bullet fired upward. Rather, they shift to longer wavelengths (Figure 12-33), an effect we see in the spectra of some white dwarfs, whose light appears redder than it would if this effect did not occur. This shift of wavelengths leaving the vicinity of a massive object is called gravitational redshift.

373

General relativity has been confirmed again and again, as seen in these observations:

Light is measurably deflected by the gravitational curving of space due to the presence of matter like stars (see Figure 12-

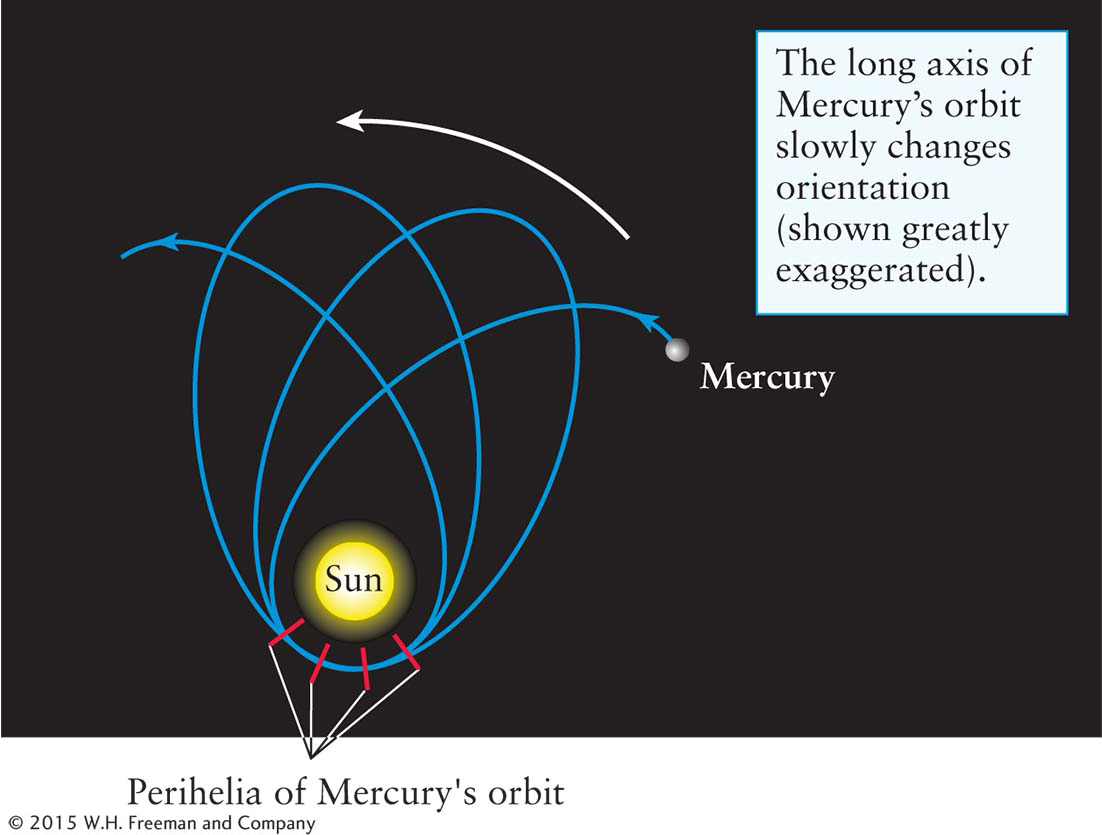

32 ) or entire galaxies containing billions of stars.The perihelion position of Mercury as seen from the Sun shifts, or precesses, by 43 arcsec per year more than is predicted by Newtonian gravitational theory (Figure 12-34). Its actual precession is exactly the amount predicted by general relativity.

The orbits of stars in binary systems follow the paths predicted by general relativity rather than those predicted by Newtonian gravitation.

The spectra of stars are observed to have the gravitational redshifts predicted by general relativity (see Figure 12-

33 ).

General relativity predicts the fate of massive star cores—

Focus Question 12-15

Does light change direction as it goes past Earth? Why or why not?

374

We can use the equations of general relativity to understand the fate of collapsing neutron stars. We just saw that all matter warps the space around itself (see Figures 12-

Focus Question 12-16

Why do neutron stars of more than about 3 M⊙ collapse to form black holes?

If light, the fastest moving of all known things, cannot escape from the vicinity of such dense matter, then nothing can! These regions out of which no matter or any form of electromagnetic radiation can leave are called black holes. Plummeting in on itself, a collapsing neutron star becomes so dense that it ceases to consist of neutrons. General relativity predicts that in creating a black hole, matter compresses to infinite density (and zero volume), a state called a singularity. However, we know that general relativity and our other theories of physics are invalid in such a situation. A more comprehensive theory of nature must be developed to explain the state of matter in a black hole’s singularity. Efforts are under way to develop such a theory. The best-

If light, the fastest moving of all known things, cannot escape from the vicinity of such dense matter, then nothing can! These regions out of which no matter or any form of electromagnetic radiation can leave are called black holes. Plummeting in on itself, a collapsing neutron star becomes so dense that it ceases to consist of neutrons. General relativity predicts that in creating a black hole, matter compresses to infinite density (and zero volume), a state called a singularity. However, we know that general relativity and our other theories of physics are invalid in such a situation. A more comprehensive theory of nature must be developed to explain the state of matter in a black hole’s singularity. Efforts are under way to develop such a theory. The best-