5-2 Astronomers have at least seven different ways of detecting planets outside our solar system

Planets were first observed orbiting other stars in 1992. Astronomers use a variety of different methods to detect these planets. Each method provides different, and sometimes complimentary, information about the planets and the stars they orbit.

Planets were first observed orbiting other stars in 1992. Astronomers use a variety of different methods to detect these planets. Each method provides different, and sometimes complimentary, information about the planets and the stars they orbit.

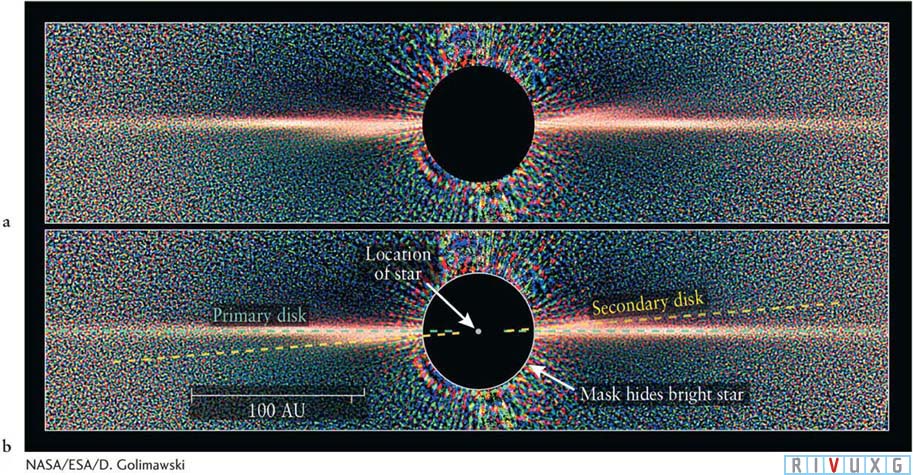

Distorted protoplanetary disksIndirect observational evidence for the existence of planets outside the solar system, called exoplanets or extrasolar planets, first came from the observed distortions of protoplanetary disks. If one or more planets orbit in a protoplanetary disk around a young star, their gravitational pull will affect the disk of gas and dust around the star, causing the disk to clump or warp or become off-

115

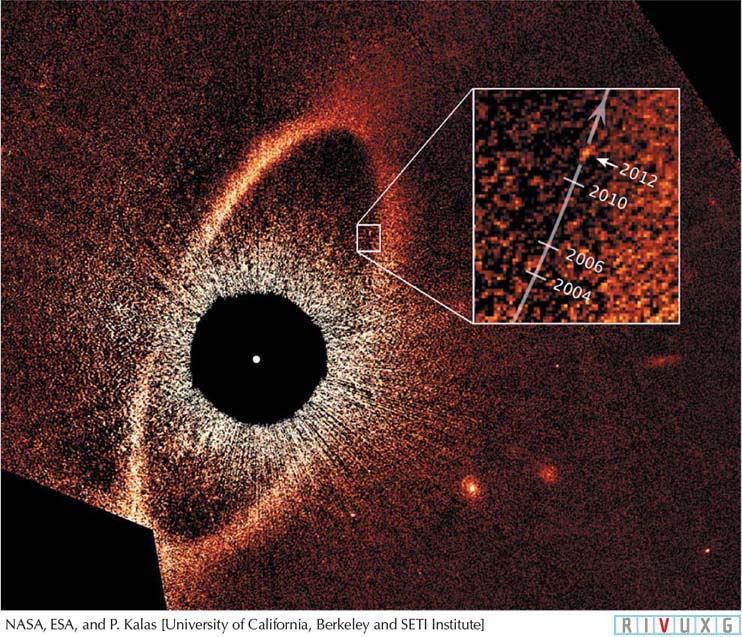

This interaction between planets and disks is seen in other systems. The nearby star Fomalhaut has an off-

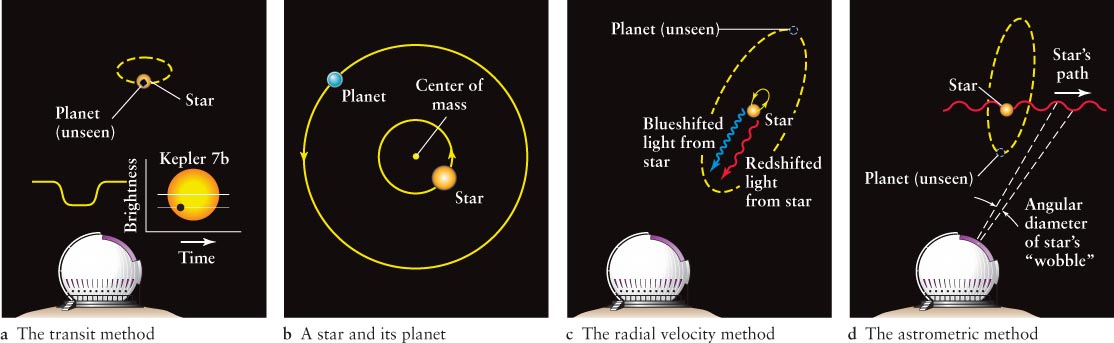

Transit photometry methodWhereas observing distorted protoplanetary disks was one of the first methods of discovering exoplanets, the most successful method has been to look for exoplanets in older systems that block some of their star’s light as the planet transits between its star and Earth. In these systems, the disks have already dissipated. Because most planets are not located between us and the stars they orbit for very long, using this technique requires watching a fixed set of stars continuously over a period of years for brightness variations caused by transits. NASA’s Kepler space telescope, which operated between 2009 and 2013, is to date the most successful collector of transit photometry; it stared continuously at over 100,000 stars, continually recording their brightnesses. When planets passed between one of these stars and us, the star’s brightness dipped, as shown in Figure 5-2a.

By the time it failed, Kepler had identified 3846 candidate planets by the light curves of their stars. Some of these variations in intensity were due to pairs of orbiting stars eclipsing each other (rather than the passage of a planet), high-

Radial velocity methodThe second most common method of detecting exoplanets uses the fact that the expression “planets orbit stars” is only an approximation to the actual activity of star–

116

When a massive exoplanet is orbiting close to its star, their center of mass is not near the star’s center. As a result, if the planet has any motion toward and then away from us in its orbit, then so, too, does its star. We can detect this motion through the Doppler shift of the star’s spectrum (as presented in Section 3-

Astrometric methodThe radial velocity method used the fact that many planets can make their stars periodically move toward and then away from us. Many planets can also make their stars appear to wobble on the celestial sphere. Many planets orbit their stars with a component of their motion perpendicular to our line of sight—

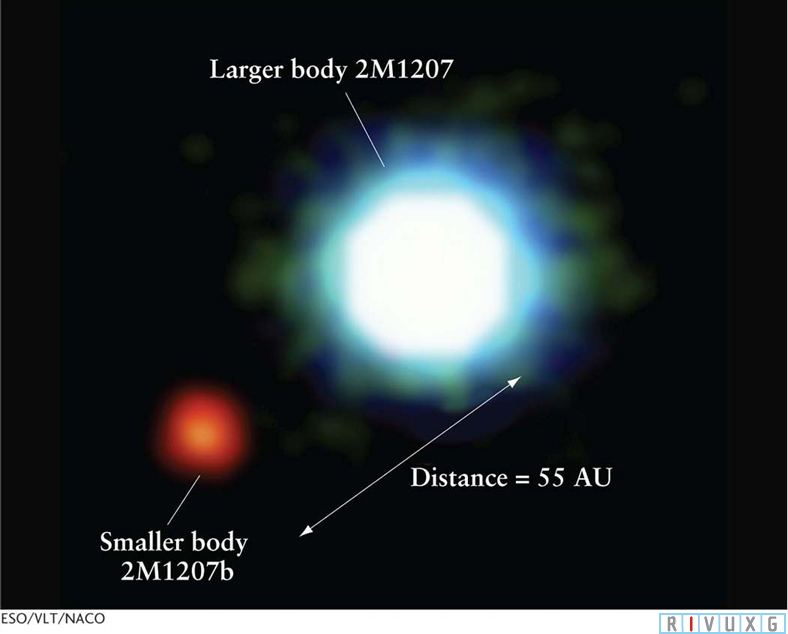

Direct imaging methodWe cannot yet resolve most of the planets we have detected. Direct imaging is extremely challenging because even planets like Jupiter, which scatter most of the light that strikes them, are very dim compared to the stars they orbit. As mentioned in Chapter 4, in order to be classified as a star, an object has to have sufficient mass to compress its insides enough to force fusion to occur in its core. The lowest mass for which this can happen is about 0.08 M⊙ (solar masses), which is equal to about 75 MJupiter. Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that the first planetlike body orbiting another object outside the solar system, directly imaged in 2004, was one in which the second object, called a brown dwarf labeled 2M1207, is not quite a star; it has only 0.025 M⊙, so no fusion occurs in it. A brown dwarf is much dimmer than a star so that it does not overwhelm the light from the planetlike body (Figure 5-3).

The smaller companion to 2M1207, denoted 2M1207b, has a mass between 5 and 8 times the mass of Jupiter. Because the larger body does not shine brightly, the dimmer, planetlike body is easily visible. However, because the larger body is not a star, the smaller one is not considered a planet.

Combining observations of disks of gas and dust around young stars and direct imaging, the planet Fomalhaut b was first observed in 2004 (Figure 5-4). This exoplanet has an extremely eccentric orbit (much more so than any planet in our solar system). Its orbit ranges from 5 to 29 times further from its star than Saturn is from the Sun. The pull of the planet (and possibly others) is so great that the center of Fomalhaut’s disk is displaced 15 AU from the star (1 AU is the average distance from Earth to the Sun). Furthermore, it appears Fomalhaut b will enter the disk in 2032, causing great havoc as it pulls some of the orbiting debris onto itself and flinging other debris out of orbit.

117

Besides Fomalhaut b, 16 other planets have been resolved. These are all large planets that are bright in the light scattered from their stars (Figure 5-5).

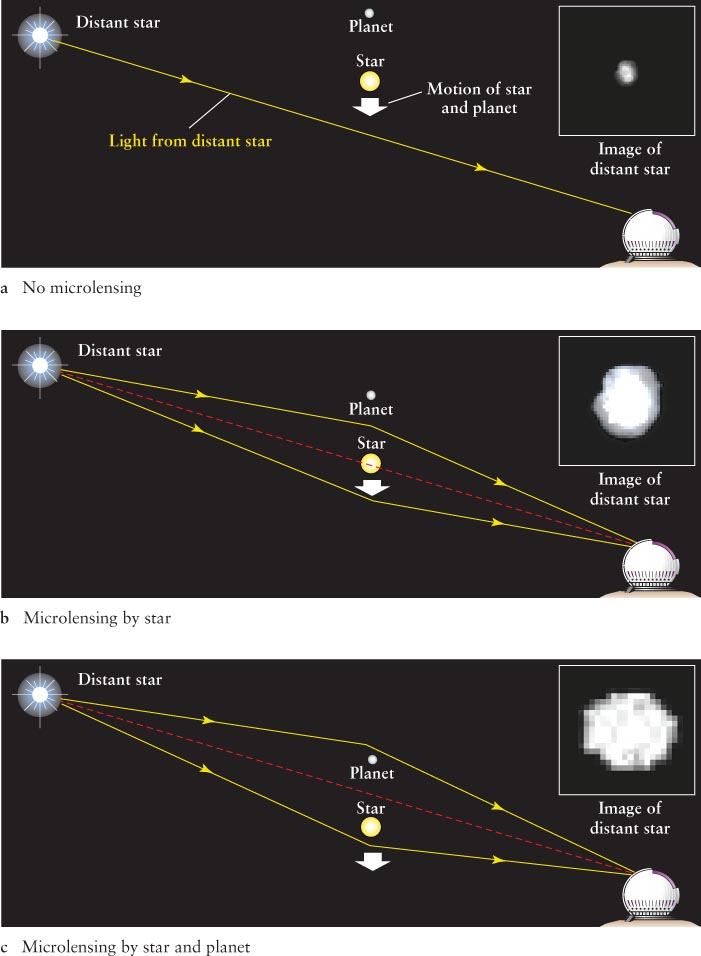

Microlensing methodIn 2004, astronomers began finding exoplanets by using a property of space that Albert Einstein discovered. His theory of general relativity, which we explore in detail in Chapter 12, shows that matter warps its surrounding space, causing, among other effects, passing light to change direction. This phenomenon is quite analogous to how light passing through a lens changes direction and is focused—

Pulsar timing methodOne of the rarest methods for detecting planets is their influence on the remnants of stars. All stars evolve, meaning that their chemistry, size, temperature, and other properties all change with time.

118

Eventually they stop fusing and either explode or simply die out. Stars with between 8 and 25 M⊙ explode as powerful supernovae that leave cores of between 1.4 and 3 M⊙ composed nearly entirely of neutrons. Many of these neutron stars are rotating hundreds or thousands of times a second and, like the Sun, they have magnetic fields that whip around with the rotation of the neutron star. These whirling magnetic fields generate pulses of radio waves, visible light, and other radiation; hence, they are called pulsars. If we are in the line of sight of the pulses, then we see them. Pulsars emit among the most regular pulses that we have ever detected, far more precisely than, for example, the most accurate wristwatch.

If a pulsar has planets orbiting it, then the motion of the pulsar around the center of mass of the planet(s)–pulsar system can be detected in the changes in the timing of its pulses. Despite the fact that pulsars are extremely rare compared to stars that are still shining by fusion, the first exoplanets ever discovered were found because of their effects on pulsar timing. Two planets were detected orbiting the pulsar PSR B1257+12 in 1992 and a third was detected in its orbit in 1994. It is worth noting that other methods of detecting exoplanets are being developed.

A Circumstellar Disk of Matter (a) Hubble view of Beta Pictoris, an edg

A Circumstellar Disk of Matter (a) Hubble view of Beta Pictoris, an edg Image of an Almost Extrasolar Planet This infrared image, taken at the European Southern Observatory, shows the two bodies 2M1207 and 2M1207b. Neither is quite large enough nor massive enough to be a star, and evidence suggests that 2M1207b did not form from a disk of gas and dust surrounding the larger body; hence, it is not a planet. This system is about 170 ly from our solar system in the constellation Hydra.

Image of an Almost Extrasolar Planet This infrared image, taken at the European Southern Observatory, shows the two bodies 2M1207 and 2M1207b. Neither is quite large enough nor massive enough to be a star, and evidence suggests that 2M1207b did not form from a disk of gas and dust surrounding the larger body; hence, it is not a planet. This system is about 170 ly from our solar system in the constellation Hydra.