Language Development in Infancy

Slide 1 of 15: Introduction

Author

S. Stavros Valenti, Hofstra University

Synopsis

In this activity, you will observe the typical course of language development in infancy from early coos and babbling to first words and simple sentences. Video clips will illustrate the early milestones of language development.

References

Lightfoot, C., Cole, M. & Cole, S. R. (2009). The Development of Children, Sixth Edition. New York: Worth Publishers.

Pinker, S. (1994). The language instinct: How the mind creates language. New York: Harper Collins.

Slide 2 of 15: Born to Talk!

It is difficult to imagine a more uniquely human attribute than language. Around the world, most babies are speaking their first words near their first birthdays. By age two, many infants are speaking with simple two‐word phrases. By age three, most toddlers are language pros as they are speaking in full grammatical sentences most of the time. How do infants learn language so quickly?

Language can be best understood as almost an instinct, a pattern of activity that is typical and comes naturally for humans. However, language differs from instincts in that it depends critically on social interaction with caregivers and other people.

In this activity, you will observe infants as their skills in speaking and listening emerge over the first two years. As you follow the path of their development, you will examine how babies “play” with language just for the fun of it and how they grow to use language to help meet their needs and wants.

Slide 3 of 15: Can We Communicate Shortly After Birth?

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

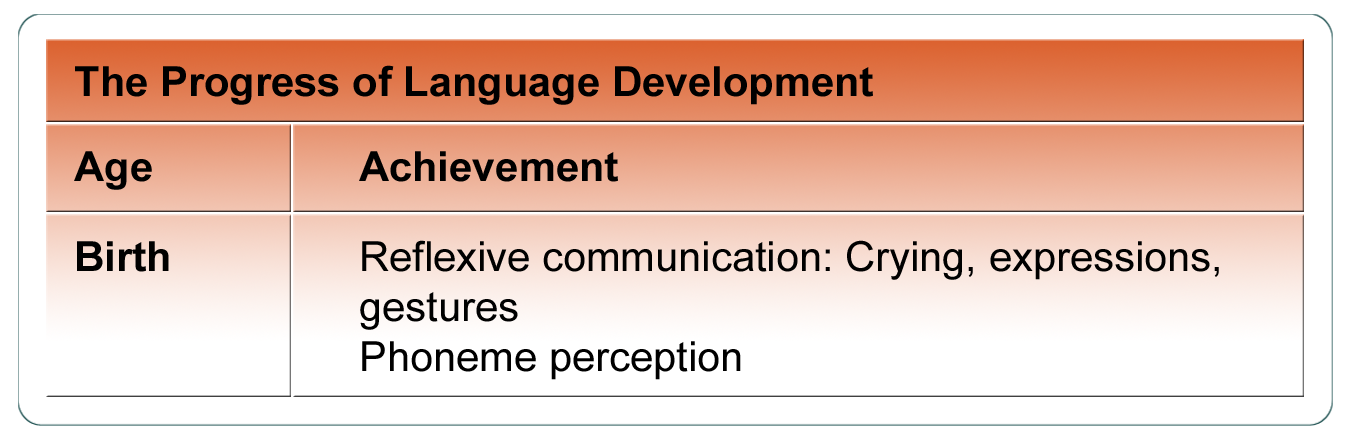

Infants are equipped to learn language even before birth. During prenatal development, the fetus’s brain is being prewired for learning language. Auditory experiences in the few months before birth also contribute to infant language learning. In the first few days of life, human infants prefer human speech to other sounds, and even further, if given a choice, they prefer the sound of their mother’s voice to that of an unfamiliar woman. Although newborns cannot produce the actual sounds of language, they already demonstrate phoneme discrimination, which is the ability to hear the important distinctions among the basic sounds of language.

This video presents a typical newborn “communicating.” At this age, reflexive crying is an automatic signal telling caregivers, “I need something now!”

Slide 4 of 15: What's New at Two Months?

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

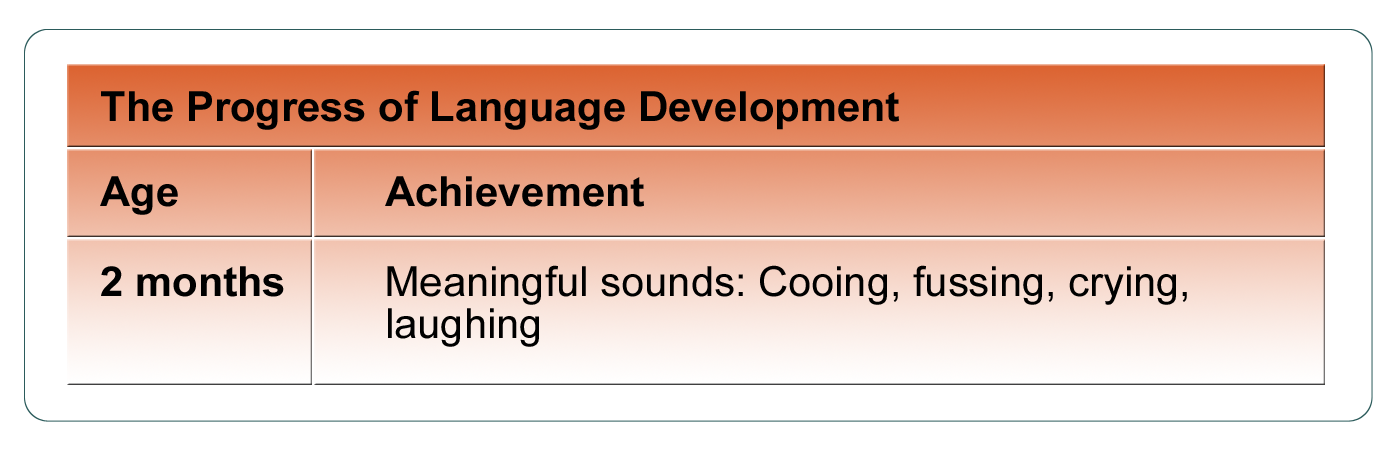

At two months, an infant will generally be making lots of sounds, some of which she will never use in speech later on. You can think of the infant at this age as having just discovered a new toy, her own speech apparatus! She needs to fiddle around with her tongue, lips, vocal cords, and breathing to learn how to coordinate them all effectively for the words and sentences that she will begin speaking later on in her first year.

Slide 5 of 15: Growling and Voweling at Three Months

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

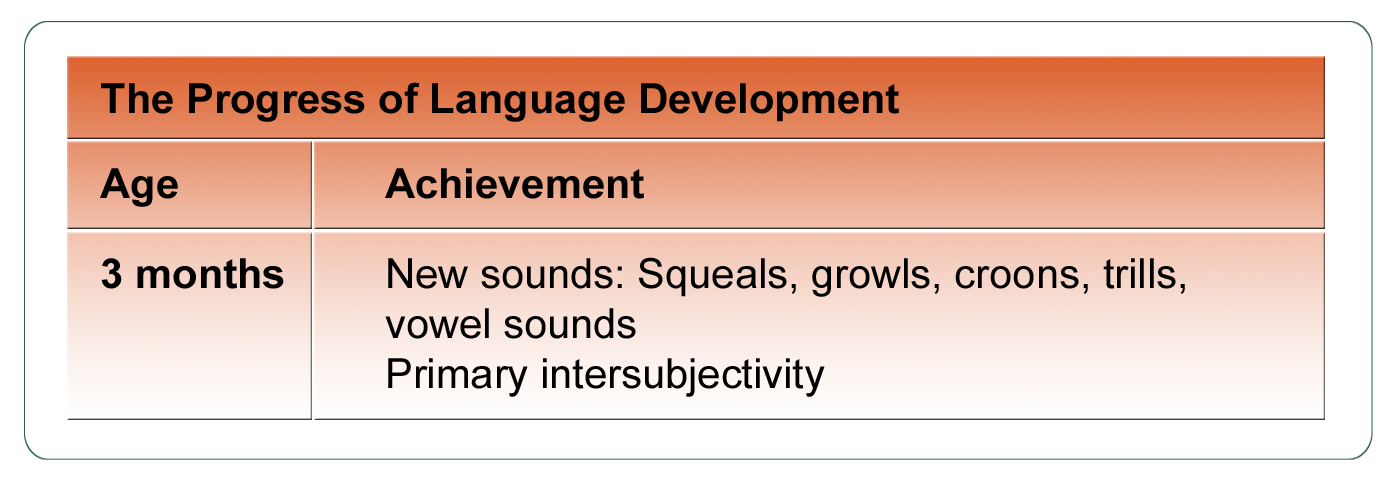

At three months, the infant’s desire to play with sounds is as strong as ever. In addition to the cooing, crying, and fussing of the earlier months, you can hear an array of new sounds from the infant, such as growls, croons, trills, and a variety of vowel sounds.

By three months of age, the quality of the bond between the caregiver and the infant has strengthened. Because the infant’s visual acuity has improved, she has developed an increased ability to detect and respond to the facial expressions of people in her world. The caregiver now finds it much easier to elicit squeals of delight during playful face‐to‐face interaction. This interaction in which each participant focuses on the emotional expressions of the other is known as primary intersubjectivity.

Slide 6 of 15: Babbling at Six Months

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

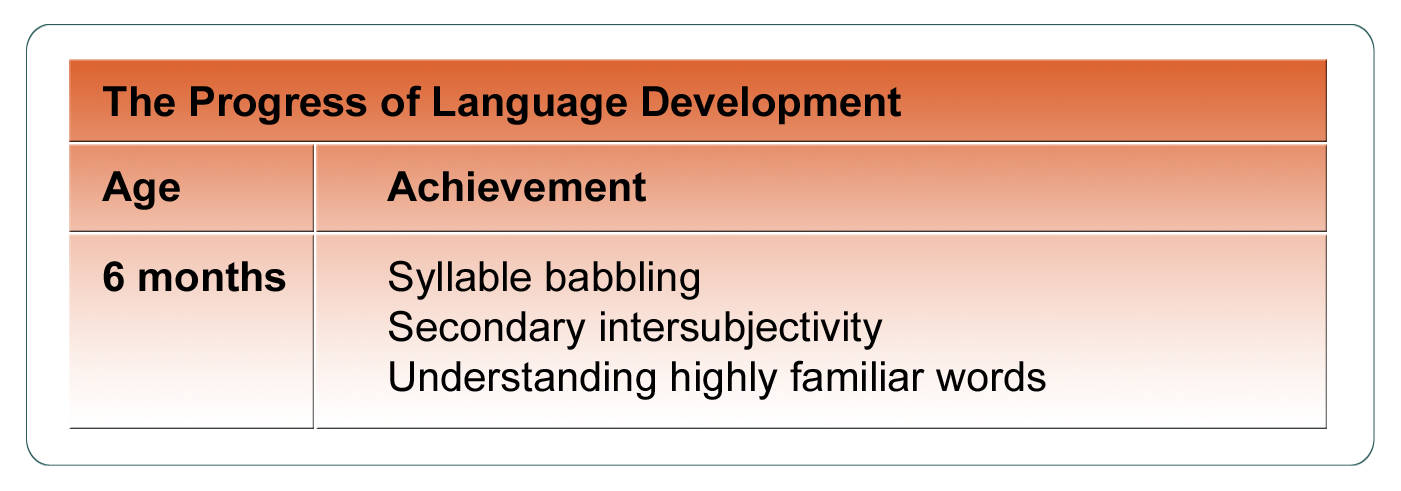

Around the time that the infant is able to sit without support, she becomes more interested in objects in her environment. You are likely to see infants at this age gesture to and make sounds at objects that have captured their attention. Some of these sounds take the form of syllable babbling, which is a repetition of syllables, such as “ba‐ba‐ba‐ba,” “da‐da‐da‐da,” “dee‐dee‐dee,” or “ma‐ma‐ma.”

At this age, the infant may respond appropriately to highly familiar words. She may look at a cup when a caregiver says, “More juice?” or look at Dad when a caregiver says, “Where is Daddy?”

When the infant and the caregiver begin to share an awareness of objects in their environment such that they both look at and gesture to and make sounds at objects, developmental psychologists refer to this behavior as secondary intersubjectivity.

Slide 7 of 15: More Babbling at Nine Months

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

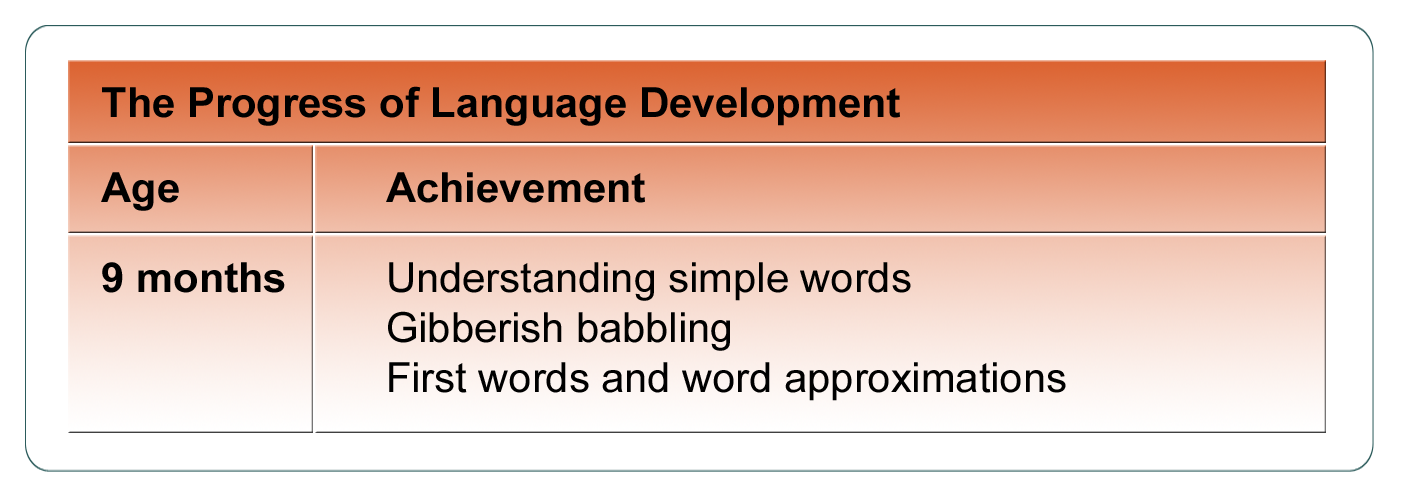

At nine months, infants are much more active in the exploration of their worlds. As they move about, caregivers will say the names of objects and people that the child encounters. Hearing these labels helps infants to understand a few words before they can actually speak them.

At this age, infants engage in gibberish babbling, a repetition of syllables with variations. For example, you may hear them say “da‐dee” or “neh‐nee.”

Slide 8 of 15: Speaking Real Words at 12 Months

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

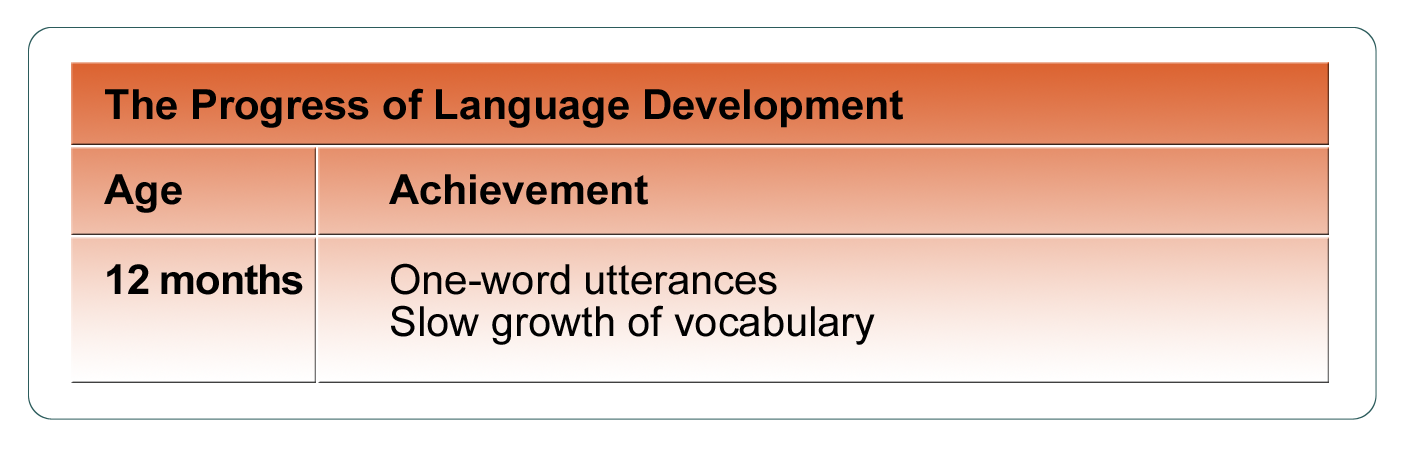

Between 9 and 12 months, infants begin to understand words, and around the time of their first birthday, they begin to speak them. A large proportion of these early words are names for objects, such as foods (“juice,” “milk”), body parts (“nose,” “eye”), clothing (“diaper,” “shirt”), toys (“block,” “teddy”), animals (“cat,” “dog”), and people (“dada,” “mama”). Other words are for actions (“open,” “shut”), motions (“up,” “down”), routines (“bye‐bye,” “done”), and modifiers (“hot,” “yuckie”). In general, a child will begin to understand a word in a preliminary way before she can say it.

Here is a way to remember when infants typically begin to use words: “Talking comes on the heels of walking.” Walking, of course, usually starts around the first birthday.

Slide 9 of 15: Zooming Through Vocabulary at 18 Months

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

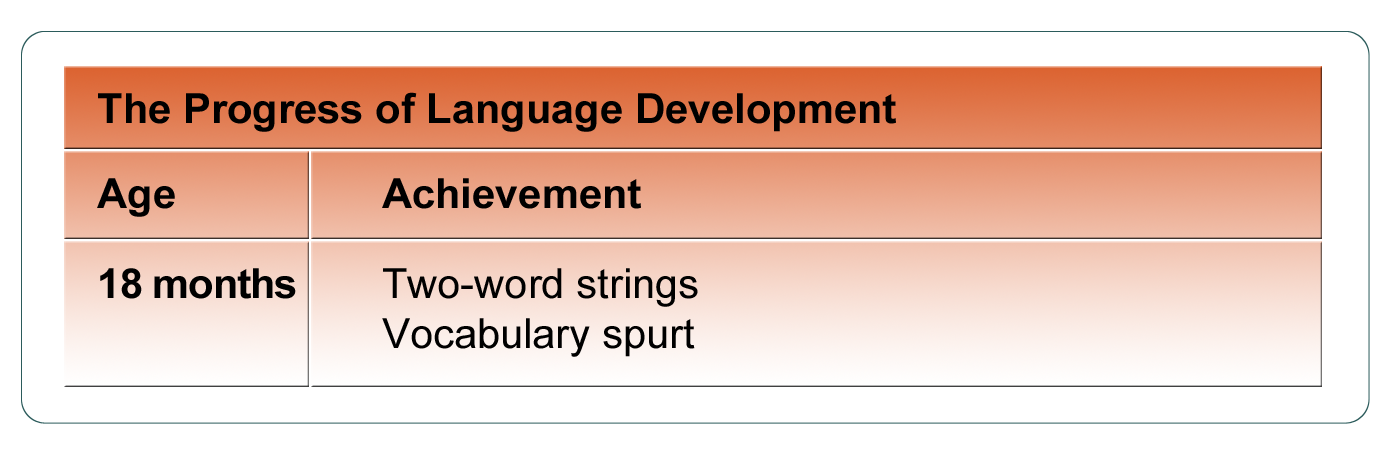

Children learn their first 50 words rather slowly over the first 18 months. Around the middle of the second year, an infant begins to acquire new words at a much faster rate of about one word every two waking hours, and that is a minimum rate! This is also the approximate time that some infants will begin to make two‐word utterances, such as “more milk” or “bye‐bye dada.”

The rate of language development is not the same for all children, and differences among children become more pronounced as they get older. One child may produce single words for about two months and then start to utter two‐word strings. Another child may speak only single words for 12 months before beginning to produce two‐word strings.

Slide 10 of 15: Simple Sentences at 24 Months

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

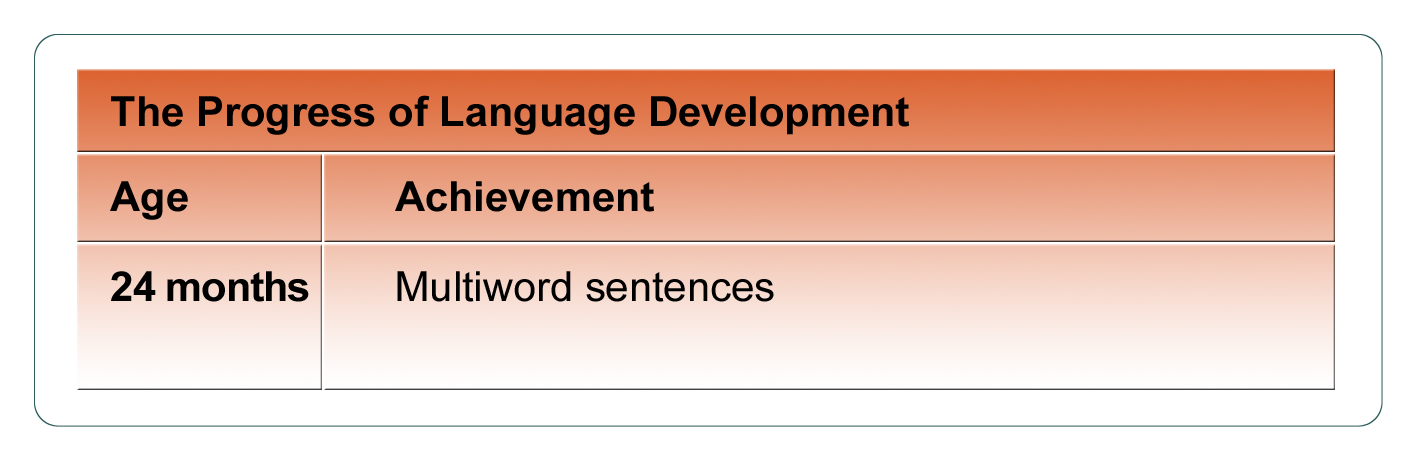

It is hard to believe that these children spoke their first words about a year ago! Toddlers at about 2 years typically speak in simple sentences that contain only the most important words, such as “Why you go?” This manner of speech is called telegraphic speech because, like a telegraph, it contains only the most important words for getting a message across but does not contain the little but important grammatical bits, known as grammatical morphemes.

Slide 11 of 15: Summary of Language Development in Infancy

Let us review the main features of early language learning in infancy.

- From birth to 6 months, infants’ communicative sounds increase and move beyond cries to include cooing, laughing, squeals, trills, vowel sounds, and babbling. They hear differences among speech sounds and begin exploring and practicing their own vocal skills.

- Between 6 and 12 months, infants begin to make more complex “gibberish” sounds and gradually produce their first words.

- From 12 to 18 months, vocabulary grows slowly, but infants understand more words than they can say.

- Between 18 and 24 months, most infants will show a rapid boost in vocabulary and will attempt their first simple phrases and sentences.

Children all over the world learn to communicate with language in more or less the same progression. Developing language does require an infant to be part of social routines but does not require explicit teaching. In that sense, language is a uniquely human aptitude.

Slide 12 of 15: Assessment: Check Your Understanding

Slide 13 of 15: Assessment: Check Your Understanding

Slide 14 of 15: Assessment: Check Your Understanding

Slide 15 of 15: Assessment: Check Your Understanding

Congratulations! You have completed this activity.Total Score: x out of x points (x%) You have received a provisional score for your essay answers, which have been submitted to your instructor.