Theory of Mind

Slide 1 of 12: Synopsis

Author

Lisa Huffman, Ball State University

S. Stavros Valenti, Hofstra University

Synopsis

In this activity, you will consider the childhood development of a theory of mind, the basic understanding of one’s own and others’ mental processes. You will review some of the research on the components of children’s theory of mind and the age range at which children develop this capacity. You will then see videos of children of various ages performing false-belief tasks.

References

Gopnik, A., & Astington, J. W. (1988). Children’s understanding of representational change and its relation to the understanding of false-belief and the appearance reality distinction. Child Development, 59, 26–37.

Jenkins, J. M., & Astington, J. W. (1996). Cognitive factors and family structure associated with theory of mind development in young children. Developmental Psychology, 32, 70–78.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition, 13, 103–128.

Slide 2 of 12: What is a “Theory of Mind”?

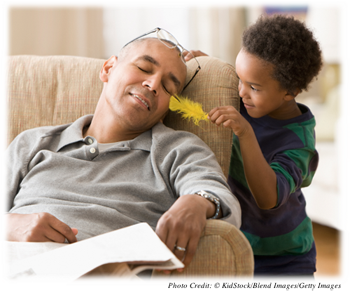

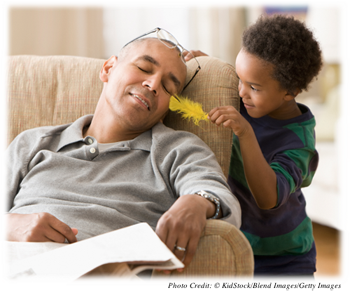

As children grow, their understanding of mental processes becomes more sophisticated. Children under three years of age have a difficult time understanding that individuals can have different viewpoints, intentions, and beliefs. However, older children are often able to make predictions about what others might be thinking and can even use their knowledge of other people’s minds to play a trick!

Developmentalists use a task called the false-belief problem to help determine whether children have acquired a theory of mind, which is a basic understanding of how the mind works and how it influences behavior.

Slide 3 of 12: Components of a Theory of Mind

Research indicates that all around the world, a major shift in children’s representational ability occurs at about age three or four when they become able to make an inference about another person’s viewpoint. This representational shift is also reflected in children’s language. By the age of two and a half, most children use words such as “think,” “know,” and “pretend.” At about age three, children understand that mental processes occur inside of your head and are different from things that exist outside of your body. For example, when asked if they can touch a dream, a three year old will likely say “no” because dreams are in your “mind.”

Siblings also seem to affect the development of a theory of mind. Children from larger families perform better on false-belief tasks, and this result suggests that older brothers and sisters may help younger siblings understand the concept of the “mind” by talking about their feelings, thoughts, and beliefs.

Slide 4 of 12: Younger Children and a False-Belief Task

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

In this video, you will see a reenactment of the classic false-belief task. In this experiment, a researcher shows a child a crayon box and asks what the child thinks is inside the box. When the researcher opens the box, the child sees that it actually contains chocolate candies. When the child is asked what someone who is not in the room (i.e. her mother) and has never seen this crayon box would think was in the box, younger children say “candies” as if everyone would know whatever they know!

Slide 5 of 12: Younger Children and a False-Belief Task (continued)

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

Slide 6 of 12: A Four-Year-Old and a False-Belief Task

There is a clear shift in reasoning ability on this task between the ages of three and five. Older children are better able to understand that someone seeing the box for the first time will think that the box contains crayons. In other words, these older children understand that everyone has their own individual thoughts.

Observe this three-year-old in the false-belief task.

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

Slide 7 of 12: Deceiving Others

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

Before children develop a clear theory of mind, they are unable to deceive those around them. To play a trick on someone, a child must comprehend that he/she can manipulate another person’s reality. For example, a child with a theory of mind understands that he/she can know where an object is hidden and that another person does not automatically know where that object is. With a theory of mind, a child realizes that his/her perception of reality is distinct from another person’s perception.

As you observed in the videos on the previous screens, children before the age of three or four act as if what they know is the reality or truth that is known by everyone. Therefore, before a child develops a theory of mind, he/she is unable to play a hiding or deception game.

Play the video to watch these two- to six-year-old children attempt a simple hiding game.

Slide 8 of 12: What Can We Conclude?

As you observed in the video clips, there is a clear shift in reasoning ability between the ages of three and five. Older children are able to understand how a trick or a hiding game works and are even able to participate in a deception.

This newly developed ability in the art of misleading someone demonstrates that the older children are able to actually comprehend what another might be seeing or understanding about a particular situation and how that perception may differ from the truth.

The development of theory of mind will continue throughout childhood and be reflected in advances of children’s representational abilities.

Slide 9 of 12: Assessment: Check Your Understanding

Slide 10 of 12: Assessment: Check Your Understanding

Slide 11 of 12: Assessment: Check Your Understanding

Slide 12 of 12: Assessment: Check Your Understanding

Congratulations! You have completed this activity.Total Score: x out of x points (x%) You have received a provisional score for your essay answers, which have been submitted to your instructor.