INTRODUCTION:

What Is Psychology?

KEY THEME

Today, psychology is defined as the science of behavior and mental processes, a definition that reflects psychology’s origins and history.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the goals and scope of contemporary psychology?

What roles did Wundt and James play in establishing psychology?

What were the early schools of thought and approaches in psychology, and how did their views differ?

Psychology is formally defined as the scientific study of behavior and mental processes. But this definition is deceptively simple. As you’ll see in this chapter, the scope of contemporary psychology is very broad—

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that the field of psychology focuses primarily on treating people with psychological problems and disorders?

Many people think that psychologists are primarily—

The four basic goals of psychology are to describe, predict, explain, and control or influence behavior and mental processes. To illustrate how these goals guide psychological research, think about our classroom discussion. Most people, like Jenna in the Prologue, have an intuitive understanding of what the word stress refers to. Psychologists, however, seek to go beyond intuitive or “common sense” understandings of human experience.

Here’s how psychology’s goals might help guide research on stress:

Describe: Trying to objectively describe the experience of stress, Dr. Garcia studies the sequence of emotional responses that occur during stressful experiences.

Predict: Dr. Kiecolt investigates responses to different kinds of challenging events, hoping to be able to predict the kinds of events that are most likely to evoke a stress response.

Explain: Seeking to explain why some people are more vulnerable to the effects of stress than others, Dr. Lazarus studies the different ways in which people respond to natural disasters.

Control or Influence: After studying the effectiveness of different coping strategies, Dr. Folkman helps people use those coping strategies to better control their reactions to stressful events.

How did psychology evolve into today’s diverse and rich science? We begin this introductory chapter by stepping backward in time to describe the early origins of psychology and its historical development. As you become familiar with how psychology began and developed, you’ll have a better appreciation for how it has come to encompass such diverse subjects. Indeed, the early history of psychology is the history of a field struggling to define itself as a separate and unique scientific discipline. The early psychologists debated such fundamental issues as:

What is the proper subject matter of psychology?

What methods should be used to investigate psychological issues?

Should psychological findings be used to change or enhance human behavior?

These debates helped set the tone of the new science, define its scope, and set its limits. Over the past century, the shifting focus of these debates has influenced the topics studied and the research methods used.

Psychology’s Origins

THE INFLUENCE OF PHILOSOPHY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The earliest origins of psychology can be traced back several centuries to the writings of the great philosophers. More than 2,000 years ago, the Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote extensively about topics such as sleep, dreams, the senses, and memory. Many of Aristotle’s ideas remained influential until the beginnings of modern science in the seventeenth century (Kheriaty, 2007).

At that time, the French philosopher René Descartes (1596–

Philosophers also laid the groundwork for another issue that would become central to psychology, the nature–

Such philosophical discussions influenced the topics that would be considered in psychology. But the early philosophers could advance the understanding of human behavior only to a certain point. Their methods were limited to intuition, observation, and logic.

The eventual emergence of psychology as a science hinged on advances in other sciences, particularly physiology. Physiology is a branch of biology that studies the functions and parts of living organisms, including humans. In the 1600s, physiologists were becoming interested in the human brain and its relation to behavior. By the early 1700s, it was discovered that damage to one side of the brain produced a loss of function in the opposite side of the body. By the early 1800s, the idea that different brain areas were related to different behavioral functions was being vigorously debated. Collectively, the early scientific discoveries made by physiologists were establishing the foundation for an idea that was to prove critical to the emergence of psychology—

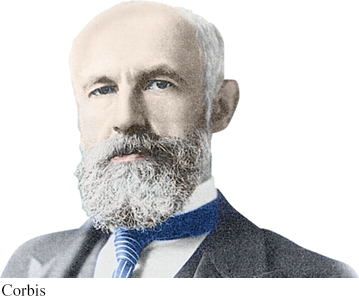

Wilhelm Wundt

THE FOUNDER OF PSYCHOLOGY

By the second half of the 1800s, the stage had been set for the emergence of psychology as a distinct scientific discipline. The leading proponent of this idea was a German physiologist named Wilhelm Wundt (Gentile & Miller, 2009). Wundt used scientific methods to study fundamental psychological processes, such as mental reaction times in response to visual or auditory stimuli. For example, Wundt tried to measure precisely how long it took a person to consciously detect the sight and sound of a bell being struck.

A major turning point in psychology occurred in 1874, when Wundt outlined the connections between physiology and psychology in his landmark text, Principles of Physiological Psychology (Diamond, 2001). He also promoted his belief that psychology should be established as a separate scientific discipline that would use experimental methods to study mental processes. In 1879, Wundt realized that goal when he opened the first psychology research laboratory at the University of Leipzig. Many mark this event as the formal beginning of psychology as an experimental science (Kohls & Benedikter, 2010).

Wundt defined psychology as the study of consciousness and emphasized the use of experimental methods to study and measure it. Until he died in 1920, Wundt exerted a strong influence on the development of psychology as a science (Wong, 2009). Two hundred students from around the world traveled to Leipzig to earn doctorates in experimental psychology under Wundt’s direction. Over the years, some 17,000 students attended Wundt’s afternoon lectures on general psychology, which often included demonstrations of devices he had developed to measure mental processes (Blumenthal, 1998).

Edward B. Titchener

STRUCTURALISM

One of Wundt’s most devoted students was a young Englishman named Edward B. Titchener. After earning his doctorate in Wundt’s laboratory, Titchener began teaching at Cornell University in New York. There he established a psychology laboratory that ultimately spanned 26 rooms.

Titchener shared many of Wundt’s ideas about the nature of psychology. Eventually, however, Titchener developed his own approach, which he called structuralism. Structuralism became the first major school of thought in psychology. Structuralism held that even our most complex conscious experiences could be broken down into elemental structures, or component parts, of sensations and feelings. To identify these structures of conscious thought, Titchener trained subjects in a procedure called introspection. The subjects would view a simple stimulus, such as a book, and then try to reconstruct their sensations and feelings immediately after viewing it. (In psychology, a stimulus is anything perceptible to the senses, such as a sight, sound, smell, touch, or taste.) They might first report on the colors they saw, then the smells, and so on, in the attempt to create a total description of their conscious experience (Titchener, 1896).

In addition to being distinguished as the first school of thought in early psychology, Titchener’s structuralism holds the dubious distinction of being the first school to disappear. Titchener’s death in 1927 essentially marked the end of structuralism as an influential school of thought in psychology. But even before Titchener’s death, structuralism was often criticized for relying too heavily on the method of introspection.

As noted by Wundt and other scientists, introspection had significant limitations. First, introspection was an unreliable method of investigation. Different subjects often provided very different introspective reports about the same stimulus. Even subjects well trained in introspection varied in their responses to the same stimulus from trial to trial.

Second, introspection could not be used to study children or animals. Third, complex topics, such as learning, development, mental disorders, and personality, could not be investigated using introspection. Ultimately, the methods and goals of structuralism were simply too limited to accommodate the rapidly expanding interests of the field of psychology.

William James

FUNCTIONALISM

By the time Titchener arrived at Cornell University, psychology was already well established in the United States. The main proponent of American psychology was one of Harvard’s most outstanding teachers—

Like many other scientists and philosophers of his generation, James was fascinated by the idea that different species had evolved over time (Menand, 2001). Many nineteenth-

In the 1850s, British philosopher Herbert Spencer had published several works arguing that modern species, including humans, were the result of gradual evolutionary change. In 1859, Charles Darwin’s groundbreaking work, On the Origin of Species, was published. James and his fellow thinkers actively debated the notion of evolution, which came to have a profound influence on James’s ideas (Richardson, 2006). Like Darwin, James stressed the importance of adaptation to environmental challenges.

In the early 1870s, James began teaching a physiology and anatomy class at Harvard University. An intense, enthusiastic teacher, James was prone to changing the subject matter of his classes as his own interests changed (B. Ross, 1991). By the late 1870s, James was teaching classes devoted exclusively to the topic of psychology.

At about the same time, James began writing a comprehensive textbook of psychology, a task that would take him more than a decade. James’s Principles of Psychology was finally published in 1890. Despite its length of more than 1,400 pages, Principles of Psychology quickly became the leading psychology textbook. In it, James discussed such diverse topics as brain function, habit, memory, sensation, perception, and emotion.

James’s ideas became the basis for a new school of psychology, called functionalism. Functionalism stressed the importance of how behavior functions to allow people and animals to adapt to their environments. Unlike structuralists, functionalists did not limit their methods to introspection. They expanded the scope of psychological research to include direct observation of living creatures in natural settings. They also examined how psychology could be applied to areas like education, child rearing, and the work environment.

Both the structuralists and the functionalists thought that psychology should focus on the study of conscious experiences. But the functionalists had very different ideas about the nature of consciousness and how it should be studied. Rather than trying to identify the essential structures of consciousness at a given moment, James saw consciousness as an ongoing stream of mental activity that shifts and changes.

Like structuralism, functionalism no longer exists as a distinct school of thought in contemporary psychology. Nevertheless, functionalism’s twin themes of the importance of the adaptive role of behavior and the application of psychology to enhance human behavior are still important in modern psychology.

WILLIAM JAMES AND HIS STUDENTS

Like Wundt, James profoundly influenced psychology through his students, many of whom became prominent American psychologists. Two of James’s most notable students were G. Stanley Hall and Mary Whiton Calkins.

In 1878, G. Stanley Hall received the first Ph.D. in psychology awarded in the United States. Hall founded the first psychology research laboratory in the United States at Johns Hopkins University in 1883. He also began publishing the American Journal of Psychology, the first U.S. journal devoted to psychology. Most important, in 1892, Hall founded the American Psychological Association and was elected its first president (Anderson, 2012). Today, the American Psychological Association (APA) is the world’s largest professional organization of psychologists, with approximately 150,000 members. (The Association for Psychological Science, founded in 1988, has about 26,000 members.)

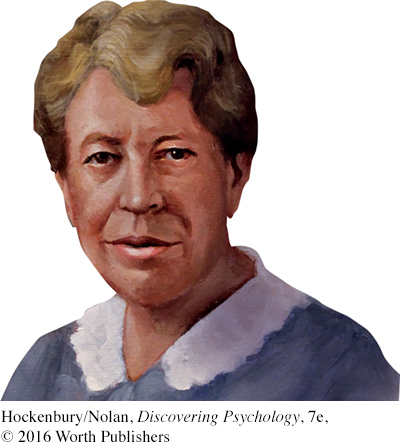

In 1890, Mary Whiton Calkins was assigned the task of teaching experimental psychology at a new women’s college—

Although never awarded the degree she had earned, Calkins made several notable contributions to psychology. She conducted research in dreams, memory, and personality. In 1891, she established a psychology laboratory at Wellesley College. At the turn of the twentieth century, she wrote a well-

For the record, the first American woman to earn an official Ph.D. in psychology was Margaret Floy Washburn, Edward Titchener’s first doctoral student at Cornell University. Washburn strongly advocated the scientific study of the mental processes of different animal species. In 1908, she published an influential text, titled The Animal Mind. Her book summarized research on sensation, perception, learning, and other “inner experiences” of different animal species. In 1921, Washburn became the second woman elected president of the American Psychological Association (Viney & Burlingame-

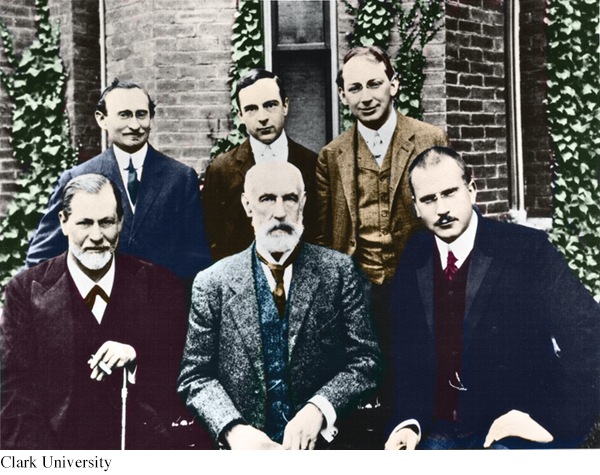

Finally, one of G. Stanley Hall’s notable students was Francis C. Sumner. Sumner was the first African American to receive a Ph.D. in psychology, awarded by Clark University in 1920. After teaching at several southern universities, Sumner moved to Howard University in Washington, D.C. While at Howard, he published papers on a wide variety of topics and chaired a psychology department that produced more African American psychologists than all other American colleges and universities combined (Guthrie, 2000, 2004). One of Sumner’s most famous students was Kenneth Bancroft Clark. Clark’s research on the negative effects of discrimination was instrumental in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision to end segregation in schools (Jackson, 2006). In 1970, Clark became the first African American president of the American Psychological Association (Belgrave & Allison, 2010).

Sigmund Freud

PSYCHOANALYSIS

Wundt, James, and other early psychologists emphasized the study of conscious experiences. But at the turn of the twentieth century, new approaches challenged the principles of both structuralism and functionalism.

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that Sigmund Freud was the first psychologist?

In Vienna, Austria, a physician named Sigmund Freud was developing an intriguing theory of personality based on uncovering causes of behavior that were unconscious, or hidden from the person’s conscious awareness. Freud’s school of thought, called psychoanalysis, emphasized the role of unconscious conflicts in determining behavior and personality. Freud himself was a neurologist, not a psychologist. Nevertheless, psychoanalysis had a strong influence on psychological thinking in the early part of the century.

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of personality and behavior was based largely on his work with his patients and on insights derived from self-

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory of personality also provided the basis for a distinct form of psychotherapy. Many of the fundamental ideas of psychoanalysis, such as the importance of unconscious influences and early childhood experiences, continue to influence psychologists and other professionals in the mental health field. We’ll explore Freud’s theory in more depth in Chapter 10 on personality and Chapter 14 on therapies.

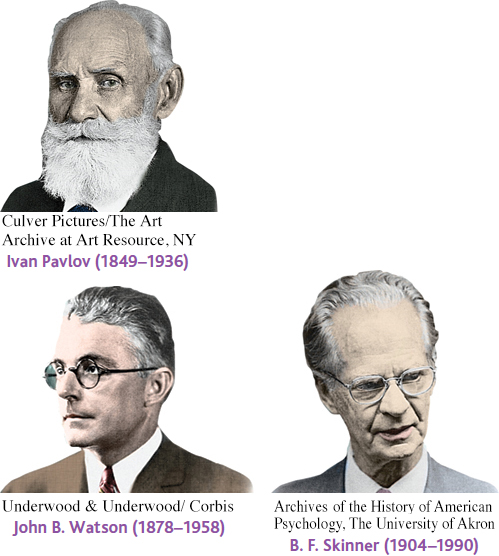

John B. Watson

BEHAVIORISM

The course of psychology changed dramatically in the early 1900s when another approach, called behaviorism, emerged as a dominating force. Behaviorism rejected the emphasis on consciousness promoted by structuralism and functionalism. It also flatly rejected Freudian notions about unconscious influences, claiming that such ideas were unscientific and impossible to test. Instead, behaviorism contended that psychology should focus its scientific investigations strictly on overt behavior—observable behaviors that could be objectively measured and verified.

Behaviorism is another example of the influence of physiology on psychology. Behaviorism grew out of the pioneering work of a Russian physiologist named Ivan Pavlov. Pavlov demonstrated that dogs could learn to associate a neutral stimulus, such as the sound of a bell, with an automatic behavior, such as reflexively salivating to food. Once an association between the sound of the bell and the food was formed, the sound of the bell alone would trigger the salivation reflex in the dog. Pavlov enthusiastically believed he had discovered the mechanism by which all behaviors were learned.

In the United States, a young, dynamic psychologist named John B. Watson shared Pavlov’s enthusiasm. Watson (1913) championed behaviorism as a new school of psychology. Structuralism was still an influential perspective, but Watson strongly objected to both its method of introspection and its focus on conscious mental processes. As Watson (1924) wrote in his classic book, Behaviorism:

Behaviorism, on the contrary, holds that the subject matter of human psychology is the behavior of the human being. Behaviorism claims that consciousness is neither a definite nor a usable concept. The behaviorist, who has been trained always as an experimentalist, holds, further, that belief in the existence of consciousness goes back to the ancient days of superstition and magic.

Behaviorism’s influence on American psychology was enormous. The goal of the behaviorists was to discover the fundamental principles of learning—how behavior is acquired and modified in response to environmental influences. For the most part, the behaviorists studied animal behavior under carefully controlled laboratory conditions.

Although Watson left academic psychology in the early 1920s, behaviorism was later championed by an equally forceful proponent—

Between Watson and Skinner, behaviorism dominated American psychology for almost half a century. During that time, the study of conscious experiences was largely ignored as a topic in psychology (Baars, 2005). In Chapter 5 on learning, we’ll look at the lives and contributions of Pavlov, Watson, and Skinner in greater detail.

Carl Rogers

HUMANISTIC PSYCHOLOGY

For several decades, behaviorism and psychoanalysis were the perspectives that most influenced the thinking of American psychologists. In the 1950s, a new school of thought emerged, called humanistic psychology. Because humanistic psychology was distinctly different from both psychoanalysis and behaviorism, it was sometimes referred to as the “third force” in American psychology (Waterman, 2013; Watson & others, 2011).

Humanistic psychology was largely founded by American psychologist Carl Rogers (Elliott & Farber, 2010). Like Freud, Rogers was influenced by his experiences with his psychotherapy clients. However, rather than emphasizing unconscious conflicts, Rogers emphasized the conscious experiences of his clients, including each person’s unique potential for psychological growth and self-

Abraham Maslow was another advocate of humanistic psychology. Maslow developed a theory of motivation that emphasized psychological growth, which we’ll discuss in Chapter 8. Like psychoanalysis, humanistic psychology included not only influential theories of personality but also a form of psychotherapy, which we’ll discuss in later chapters.

By briefly stepping backward in time, you’ve seen how the debates among the key thinkers in psychology’s history shaped the development of psychology as a whole. Each of the schools that we’ve described had an impact on the topics and methods of psychological research. As you’ll see throughout this textbook, that impact has been a lasting one. In the next sections, we’ll touch on some of the more recent developments in psychology’s evolution. We’ll also explore the diversity that characterizes contemporary psychology.

Test your understanding of The Origins of Psychology with  .

.