The Effects of Experience on Perceptual Interpretations

Our educational, cultural, and life experiences shape what we perceive. As a simple example, consider a climbing wall in a gym. If your knowledge of climbing is limited, the posts, ropes, arrows, and lines look like a meaningless jumble of equipment. But if you are an expert climber, you see handgrips and footgrips, belays, overhangs, and routes of varying difficulty. Our different perceptions of a climbing wall are shaped by our prior learning experiences.

Learning experiences can vary not just from person to person but also from culture to culture. The Culture and Human Behavior box on page 126, “Culture and the Müller-

Perception can also be influenced by an individual’s expectations, motives, and interests. The term perceptual set refers to the tendency to perceive objects or situations from a particular frame of reference. Perceptual sets usually lead us to reasonably accurate conclusions. If they didn’t, we would develop new perceptual sets that were more accurate. But sometimes a perceptual set can lead us astray. For example, someone with an avid interest in UFOs might readily interpret unusual cloud formations as a fleet of alien spacecraft. Sightings of Bigfoot, mermaids, and the Loch Ness monster that turn out to be brown bears, manatees, or floating logs are all examples of perceptual sets.

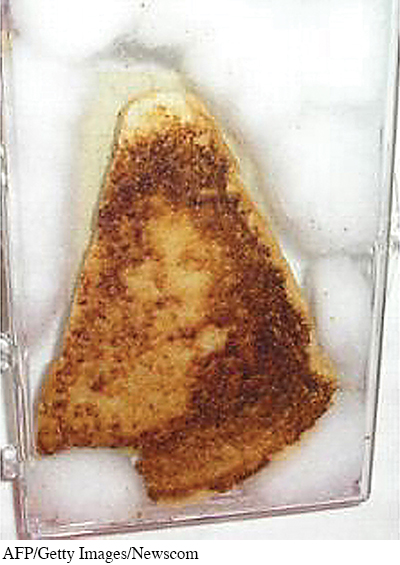

People are especially prone to seeing faces in ambiguous stimuli, as in the photos shown on previous page. Why? One reason is that the brain is wired to be uniquely responsive to faces or face-

But this extraordinary neural sensitivity also makes us more liable to false positives, seeing faces that aren’t there. Vague or ambiguous images with face-

Test your understanding of Perception and Perceptual Illusions with  .

.

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

Culture and the Müller-

Since the early 1900s, it has been known that people in industrialized societies are far more susceptible to the Müller-

Cross-

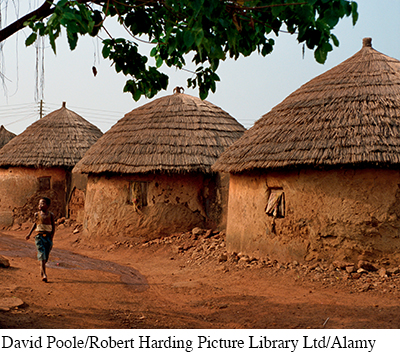

In contrast, people who live in noncarpentered cultures more frequently encounter natural objects. In these cultures, perceptual experiences with straight lines and right angles are relatively rare. Segall predicted that people from these cultures would be less susceptible to the Müller-

To test this idea, Segall and his colleagues (1963, 1966) compared the responses of people living in carpentered societies, such as Evanston, Illinois, with those of people living in noncarpentered societies, such as remote areas of Africa. The results confirmed their hypothesis. The Müller-

These findings provided some of the first evidence for the idea that culture could shape perception. As Segall (1994) later concluded, “Every perception is the result of an interaction between a stimulus and a perceiver shaped by prior experience.” Thus, people who grow up in very different cultures might well perceive aspects of their physical environment differently.