Sleep Disorders

KEY THEME

Sleep disorders are surprisingly common, take many different forms, and interfere with a person’s daytime functioning.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the two broad categories of sleep disorders?

What are insomnia, sleep apnea, and narcolepsy?

What kinds of behavior are displayed in the different parasomnias?

Data from the National Sleep Foundation’s annual polls indicate that about 7 out of 10 people experience regular sleep disruptions. Such disruptions become a sleep disorder when: (1) abnormal sleep patterns consistently occur, (2) they cause subjective distress, and (3) they interfere with a person’s daytime functioning (Thorpy, 2005; Thorpy & Plazzi, 2010).

Sleep disorders fall into two broad categories. Dyssomnias are sleep disorders involving disruptions in the amount, quality, or timing of sleep. Obstructive sleep apnea and narcolepsy are examples of dyssomnias. The parasomnias are sleep disorders involving undesirable physical arousal, behaviors, or events during sleep or sleep transitions.

Insomnia

Insomnia is not defined solely based on how long a person sleeps. Why? Put simply, because people vary in how much sleep they need to feel refreshed. Rather, insomnia is diagnosed when people repeatedly: (1) are dissatisfied with the quality or duration of their sleep; (2) experience onset insomnia, meaning that they have difficulty falling asleep, or maintenance insomnia, meaning they have difficulty staying asleep; or (3) wake before it is time to get up. Regularly taking 30 minutes or longer to fall asleep is considered to be a symptom of insomnia. These disruptions must also produce daytime sleepiness, fatigue, impaired social or occupational performance, or mood disturbances (Bootzin & Epstein, 2011).

Insomnia is the most common sleep complaint among adults. Although many people occasionally have trouble falling asleep, about 10% of adults experience chronic insomnia for a month or longer (Mahowald & Schenck, 2005).

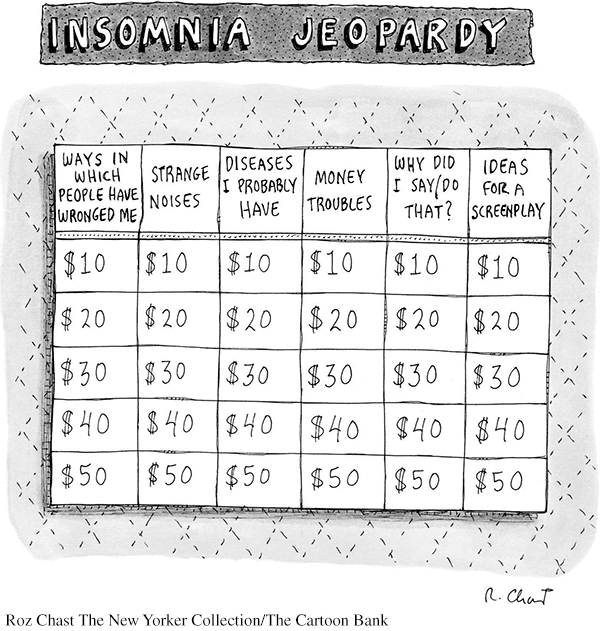

One common cause of insomnia is hyperarousal (Salas & others, 2014). Excitement about an upcoming event or the use of stimulants, like nicotine and caffeine, can make it hard to fall asleep. Most commonly, insomnia can be traced to anxiety over stressful life events, such as job, school, or relationship difficulties. Sometimes, worry about inadequate sleep can itself cause insomnia. Creating a vicious circle, concerns about the inability to sleep make disrupted sleep even more likely, further intensifying anxiety and worry over personal difficulties, producing more sleep difficulties, and so on (Perlis & others, 2005).

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that sleeping pills are an effective way to treat chronic insomnia?

Although the occasional use of prescription “sleeping pills” can be helpful to treat transient insomnia, frequent use, or use for chronic insomnia, is problematic. Along with having harmful side effects, they do not offer a long-

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

BLOCKED BREATHING DURING SLEEP

Excessive daytime sleepiness is a key symptom of the second most common sleep disorder. In obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the sleeper’s airway becomes narrowed or blocked, causing very shallow breathing or repeated pauses in breathing. Each time breathing stops, oxygen blood levels decrease and carbon dioxide blood levels increase, triggering a momentary awakening. Over the course of a night, 300 or more sleep apnea episodes can occur (Schwab & others, 2005).

Obstructive sleep apnea disrupts the quality and quantity of a person’s sleep, causing daytime grogginess, poor concentration, memory and learning problems, and irritability (Weaver & George, 2005). Sleep apnea can also cause physical health problems, including weight gain, high blood pressure, and diabetes. Although OSA can occur in any age group, including small children, it becomes more common as people age. It is also more common in men than women.

Sleep apnea can often be treated with lifestyle changes, such as avoiding alcohol or losing weight (Hoffstein, 2005; Powell & others, 2005). Moderate to severe cases of sleep apnea are usually treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), using a device that increases air pressure in the throat so that the airway remains open (Grunstein, 2005).

Narcolepsy

BLURRING THE BOUNDARIES BETWEEN SLEEP AND WAKEFULNESS

Even with adequate nighttime sleep, people with narcolepsy experience overwhelming bouts of excessive daytime sleepiness and brief, uncontrollable episodes of sleep. These involuntary sleep episodes, called sleep attacks or microsleeps, typically last from a few seconds to several minutes.

Most people with narcolepsy—

The Parasomnias

UNDESIRED AROUSAL OR ACTIONS DURING SLEEP

We tend to think of sleep as an “either/or” phenomenon—

The parasomnias are a collection of sleep disorders that are characterized by undesirable physical arousal, behaviors, or events during sleep or sleep transitions (Mahowald & Schenk, 2005; Schenck, 2007). A key characteristic of all of the parasomnias is first, the lack of awareness while performing the actions and second, total amnesia for the behaviors or events upon awakening.

Parasomnias occur during NREM stages 3 and 4 slow-

The parasomnias were once thought to be extremely rare, especially in adults. However, sleep researchers have discovered that some parasomnias—

SLEEP TERRORS

Also called night terrors, sleep terrors begin with a sharp increase in physiological arousal—

SLEEPWALKING AND OTHER COMPLEX BEHAVIORS DURING SLEEP

The Prologue story about Scott described several key features of another parasomnia—

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that it can be dangerous to wake a sleepwalker?

It’s difficult to rouse sleepwalkers from deep sleep. Occasionally, sleepwalkers can respond aggressively if touched or interrupted (Pressman, 2007). Scott reacted violently to being interrupted while sleepwalking at least once while he was growing up, and his attack on his wife may have been caused by her trying to wake him up and guide him back to the house (Cartwright, 2004, 2007). In most cases, though, sleepwalkers respond to verbal suggestions and can be gently led back to bed without incident.

Sleepwalking is also involved in sleep-

Also called sexsomnia, sleepsex involves abnormal sexual behaviors and experiences during sleep. Without realizing what they are doing, sleepers initiate some kind of sexual behavior, such as masturbation, groping or fondling their bed partner’s genitals, or even sexual intercourse (Trajanovic & Shapiro, 2010). Although sometimes described as loving or playful, more often sleepsex behavior is characterized as “robotic,” aggressive, and impersonal. Whether affectionate or forceful, sleepsex behavior is usually depicted as being out of character with the individual’s sexual behavior when awake (Schenck & others, 2007). As is the case in other parasomnias, the person typically has no memory of his actions the next day (Schenck, 2007).

For more information about sleep disorders, visit the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s Web site, www.SleepEducation.com, or the National Sleep Foundation’s Web site, www.SleepFoundation.org.

Finally, no discussion of the parasomnias would be complete without at least a mention of the colorfully titled exploding head syndrome. As its name implies, the unfortunate sufferer reports the sensation of loud noises that sound like gunshots or a bomb exploding inside his head while falling asleep or waking up (Sharpless, 2015a). Although painless, episodes are usually accompanied by extreme arousal and fear. Exploding head syndrome was once thought to be extremely rare, but a recent survey found that about one in five college students had experienced one or more episodes. The cause is unknown, but psychologist and exploding head syndrome researcher Brian Sharpless (2015b) likens it to a “brain hiccup.” He speculates that the sensation occurs when auditory neurons fire rather than shut down as the brain transitions between sleep and wakefulness.

Test your understanding of Sleep Disorders with  .

.