Psychoactive Drugs

KEY THEME

Psychoactive drugs alter consciousness by changing arousal, mood, thinking, sensations, and perceptions.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are four broad categories of psychoactive drugs?

What are some common properties of psychoactive drugs?

What factors influence the effects, use, and abuse of drugs?

Psychoactive drugs are chemical substances that can alter arousal, mood, thinking, sensation, and perception. In this section, we will look at the characteristics of four broad categories of psychoactive drugs:

Depressants—drugs that depress, or inhibit, brain activity.

Opioids—drugs that are chemically similar to morphine and that relieve pain and produce euphoria.

Stimulants—drugs that stimulate, or excite, brain activity.

Psychedelic drugs—drugs that distort sensory perceptions.

Common Effects of Psychoactive Drugs

Addiction is a broad term that refers to a condition in which a person feels psychologically and physically compelled to take a specific drug. People experience physical dependence when their body and brain chemistry have physically adapted to a drug.

Many physically addictive drugs gradually produce drug tolerance, which means that increasing amounts of the drug are needed to gain the original, desired effect.

When a person becomes physically dependent on a drug, abstaining from the drug produces withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms are unpleasant physical reactions to the lack of the drug, plus an intense craving for it. Withdrawal symptoms are alleviated by taking the drug again. Often, the withdrawal symptoms are opposite to the drug’s action, a phenomenon called the drug rebound effect. For example, withdrawing from stimulating drugs, like the caffeine in coffee, may produce depression and fatigue. Withdrawal from depressant drugs, such as alcohol, may produce excitability.

Each psychoactive drug has a distinct biological effect. Psychoactive drugs may influence many different bodily systems, but their consciousness-

The biological effects of a drug can vary considerably from person to person. An individual’s race, gender, age, and weight may influence the intensity of a particular drug’s effects. For example, many Asians and Asian Americans have a specific genetic variation that makes them much more responsive to alcohol’s effects. In turn, this heightened sensitivity to alcohol is associated with significantly lower rates of alcohol dependence seen among people of Asian heritage as compared to other races (Cook & others, 2005; Kufahl & others, 2008).

Psychological and environmental factors can also influence a drug’s effects. An individual’s response to a drug can be greatly affected by his or her personality characteristics, mood, expectations, and experience with the drug, as well as the setting in which the drug is taken (Kufahl & others, 2008).

In contrast, drug abuse, more formally termed substance use disorder, refers to recurrent drug use that involves difficulty controlling the use of the substance, the disruption of normal social, occupational, and interpersonal functioning, and the development of craving, tolerance, and withdrawal symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In the United States, alcohol is, by far, the most widely abused substance (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009).

The effects of psychoactive drugs are especially unpredictable when combined. At one time, most fatal drug overdoses were caused by illegal narcotics. Today, however, most of the 38,000 drug overdose deaths that occur in the United States each year are caused by prescription drugs, including painkillers, antianxiety medications, and antidepressant medications (Jones & others, 2013).

The Depressants

ALCOHOL, BARBITURATES, INHALANTS, AND TRANQUILIZERS

KEY THEME

Depressants inhibit central nervous system activity, while opioids are addictive drugs that relieve pain and produce euphoria.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the physical and psychological effects of alcohol?

How do barbiturates, inhalants, and tranquilizers affect the body?

What are the effects of opioids and how do they affect the brain?

The depressants are a class of drugs that depress or inhibit central nervous system activity. In general, depressants produce drowsiness, sedation, or sleep. Depressants also relieve anxiety and lower inhibitions. All depressant drugs are potentially physically addictive. Further, the effects of depressant drugs are additive, meaning that the sedative effects are increased when depressants are combined.

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

The Addicted Brain: Diminishing Rewards

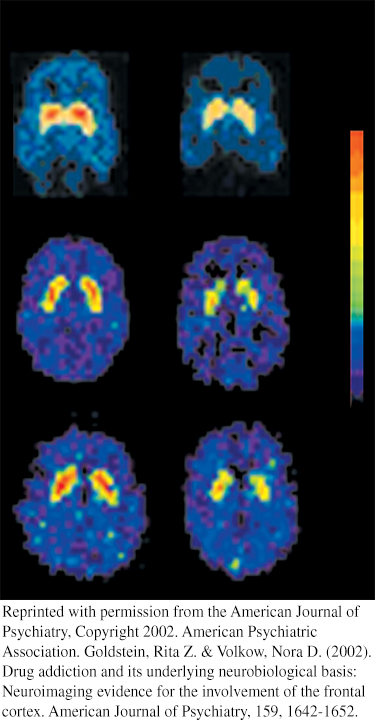

Addictive drugs include alcohol, cocaine, heroin, nicotine, and the amphetamines. Although their effects are diverse, these addictive drugs share one thing in common: They all activate dopamine-

The brain’s reward system evolved to reinforce behaviors that promote survival, such as eating and sexuality. Many pleasurable activities, including exercising, listening to music, and even looking at an attractive person, can cause a temporary increase in dopamine.

In contrast to naturally rewarding activities and substances, addictive drugs hijack the brain’s reward system. Initially, the drug produces the intense dopamine-

As the brain’s reward circuits down-

While lying in a PET scanner and viewing images of laughing children or other pleasurable scenes, the cocaine addict’s brain shows little or no dopamine response. But when shown images associated with cocaine use—

Because the neurons in the brain’s reward system have physically changed, they can remain hypersensitive to such cues associated with the abused substance for months and even years after drug use has ended. Simply being exposed to drug-

ALCOHOL

Weddings, parties, and other social gatherings often include alcohol, a tribute to its relaxing and social lubricating properties. Used in small amounts, alcohol reduces tension and anxiety. But even though it is legal for adults and readily available, alcohol also has a high potential for abuse. Partly because of its ready availability, many drug experts consider alcohol to have the highest social cost of all the addictions (Hawkey & others, 2011; Nutt & others, 2010). Consider these points:

Excessive alcohol consumption accounts for an estimated 90,000 deaths annually in the United States (Stahre & others, 2014). And, it is a factor in the deaths of over 1,400 U.S. college students each year (Chavez & others, 2011; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008).

Alcohol is involved in more than half of all assaults, homicides, and motor vehicle accidents (Advokat, Comaty, & Julien, 2014). Intoxicated drivers are the cause of more than 17,000 traffic deaths each year.

Alcohol intoxication is often a factor in domestic and partner violence, child abuse, and public violent behavior (Easton & others, 2007; Shepherd, 2007).

Drinking during pregnancy is a leading cause of birth defects. It is the most common cause of intellectual disability—

and the only preventable one (Niccols, 2007).

An estimated 17 million Americans are either dependent upon alcohol or have serious alcohol problems. They drink heavily on a regular basis and suffer social, occupational, and health problems as a result (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009).

However, the numerous adverse health and social consequences associated with excessive drinking—

What Are Alcohol’s Psychological Effects? People are often surprised that alcohol is classified as a depressant. Initially, alcohol produces a mild euphoria, talkativeness, and feelings of good humor and friendliness, leading many people to think of alcohol as a stimulant. But these subjective experiences occur because alcohol lessens inhibitions by depressing the brain centers responsible for judgment and self-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that alcohol is a stimulant?

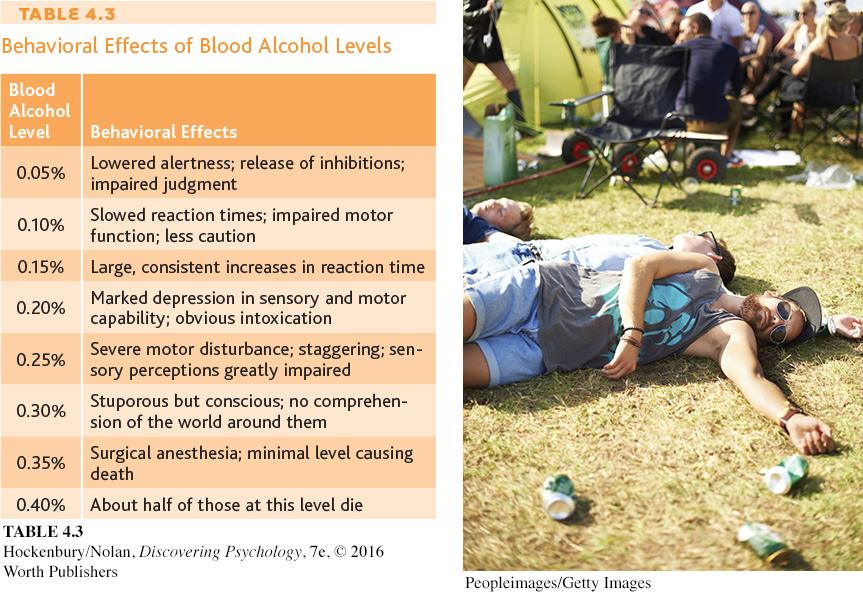

How Does Alcohol Affect the Body? As a general rule, it takes about one hour to metabolize the alcohol in one drink, which is defined as 1 ounce of 80-

Factors such as body weight, gender, food consumption, and the rate of alcohol consumption also affect blood alcohol levels. A slender person who quickly consumes three drinks on an empty stomach will become more than twice as intoxicated as a heavier person who consumes three drinks with food. Women metabolize alcohol more slowly than do men. If a man and a woman of equal weight consume the same number of drinks, the woman will become more intoxicated. Table 4.3 on the next page shows the behavioral effects and impairments associated with different blood alcohol levels.

Binge drinking is a particularly risky practice. Binge drinking is defined as five or more drinks in a row for men, or four or more drinks in a row for women (Cooke & others, 2010). Every year, several college students die of alcohol poisoning after ingesting large amounts of liquor in a short amount of time. Less well publicized are the other negative effects associated with binge drinking, including aggression, sexual assaults, accidents, and property damage (Mitka, 2009; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008).

In a person who is addicted to alcohol, withdrawal causes rebound hyperexcitability in the brain. The severity of the withdrawal symptoms depends on the level of physical dependence. With a low level of dependence, withdrawal may involve disrupted sleep, anxiety, and mild tremors (“the shakes”). At higher levels of physical dependence on alcohol, withdrawal may involve confusion, hallucinations, and severe tremors or seizures. Collectively, these severe symptoms are called delirium tremens, or the DTs. In cases of extreme physical dependence, alcohol withdrawal, in the absence of medical supervision, can cause seizures, convulsions, and even death.

INHALANTS

Inhalants are chemical substances that are inhaled to produce an alteration in consciousness. Paint solvents, spray paint, gasoline, and aerosol sprays are just a few of the substances that are abused in this way. Inhalant abuse is most prevalent among adolescent and young adult males.

Although psychoactive inhalants do not have a common chemical structure, they generally act as central nervous system depressants. At low doses, they may cause relaxation, giddiness, and reduced inhibition. At higher doses, inhalants can lead to hallucinations and a loss of consciousness.

Inhalants are very dangerous. Suffocation is one hazard, but many inhaled substances are also toxic to the liver and other organs. Chronic abuse also leads to neurological and brain damage. One study compared cognitive functioning in cocaine and inhalant abusers. Both groups scored well below the normal population, but inhalant users scored even below the cocaine abusers on problem-

BARBITURATES AND TRANQUILIZERS

Barbiturates are powerful depressant drugs that reduce anxiety and promote sleep, which is why they are sometimes called “downers.” Barbiturates depress activity in the brain centers that control arousal, wakefulness, and alertness. They also depress the brain’s respiratory centers.

Like alcohol, barbiturates at low doses cause relaxation, mild euphoria, and reduced inhibitions. Larger doses produce a loss of coordination, impaired mental functioning, and depression. High doses can produce unconsciousness, coma, and death. Because of the additive effect of depressants, barbiturates combined with alcohol are particularly dangerous. Common barbiturates include the prescription sedatives Seconal and Nembutal. The illegal drug methaqualone (street name quaalude) is almost identical chemically to barbiturates and has similar effects.

Barbiturates produce both physical and psychological dependence. Withdrawal from low doses of barbiturates produces irritability and REM rebound nightmares. Withdrawal from high doses of barbiturates can produce hallucinations, disorientation, restlessness, and life-

Tranquilizers are depressants that relieve anxiety. Commonly prescribed tranquilizers include Xanax, Valium, Librium, and Ativan. Chemically different from barbiturates, tranquilizers produce similar, although less powerful, effects. We will discuss these drugs in more detail in Chapter 14 on therapies.

The Opioids

FROM POPPIES TO DEMEROL

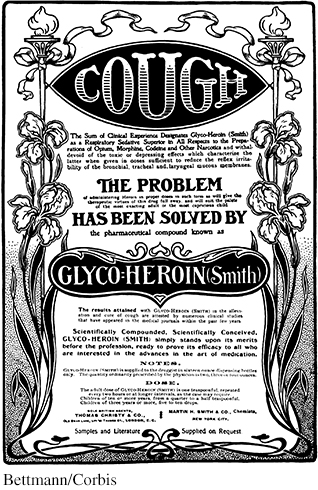

Also called narcotics or opiates, the opioids are a group of addictive drugs that are chemically similar to morphine and that relieve pain and produce feelings of euphoria. Natural opioids include opium, which is derived from the opium poppy; morphine, the active ingredient in opium; and codeine, which can be derived from either opium or morphine. Synthetic and semisynthetic opioids include heroin, methadone, oxycodone, and the prescription painkillers OxyContin, Vicodin, Percodan, Demerol, and Fentanyl.

Opioids produce their powerful effects by mimicking the brain’s own natural painkillers, called endorphins. Opioids occupy endorphin receptor sites in the brain. When used medically, opioids alter an individual’s reaction to pain not by acting at the pain site but by reducing the brain’s perception of pain. It was once believed that people who took medically prescribed opioids rarely developed drug tolerance or addiction. Today, physicians and researchers are more aware of the addictive potential of these drugs. Most patients do not abuse prescription pain pills or develop physical dependence or addiction (Noble & others, 2008; Volkow & others, 2011a).

Among the most dangerous opioids is heroin. When injected into a vein, heroin reaches the brain in seconds, creating an intense rush of euphoria that is followed by feelings of contentment, peacefulness, and warmth. Withdrawal is not life-

Heroin is not the most commonly abused opioid. That distinction belongs to the prescription pain pills, especially OxyContin, which combines the synthetic opioid oxycodone with a time-

The synthetic opioids are now the most commonly prescribed class of medications in the United States (Volkow & others, 2011a, 2011b). Abuse of OxyContin and similar prescription pain pills such as hydrocodone and oxycodone has skyrocketed in recent years. In fact, in terms of frequency of illicit use, prescription pain pills are second only to marijuana (Savage, 2005). Prescription pain pills are especially dangerous when mixed with other drugs, such as alcohol or barbiturates. Deaths from accidental overdose of opioids quadrupled between 1999 and 2010, and prescription opioids accounted for most of this increase (Volkow & others, 2014).

As access to prescription opioids has become more strictly controlled, heroin use and overdose deaths have climbed (Hedegaard & others, 2015; Kolodny & others, 2015). Much of the increase is due to people turning to heroin—

The Stimulants

CAFFEINE, NICOTINE, AMPHETAMINES, AND COCAINE

KEY THEME

Stimulant drugs increase brain activity, while the psychedelic drugs create perceptual distortions, alter mood, and affect thinking.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the general effects of stimulants and the specific effects of caffeine, nicotine, amphetamines, and cocaine?

What are the effects of mescaline, LSD, and marijuana?

What are the “club drugs,” and what are their effects?

Stimulants vary in legal status, the strength of their effects, and the manner in which they are taken. All stimulant drugs, however, are at least mildly addicting, and all tend to increase brain activity.

CAFFEINE AND NICOTINE

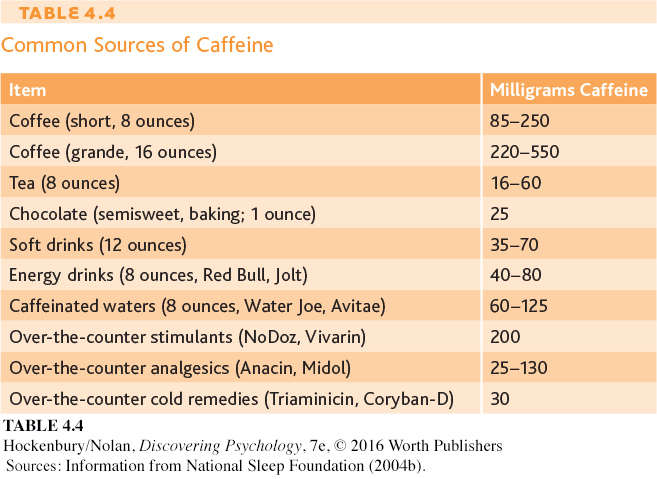

Caffeine is the most widely used psychoactive drug in the world and is found in such common sources as coffee, tea, cola drinks, chocolate, and certain over-

Caffeine also produces its mentally stimulating effects by blocking adenosine receptors in the brain. Adenosine is a naturally occurring compound in your body that influences the release of several neurotransmitters in the central nervous system. As noted earlier, adenosine levels gradually increase the longer a person is awake. When adenosine levels reach a certain level in your body, the urge to sleep greatly intensifies. Caffeine staves off the urge and promotes alertness by blocking adenosine’s sleep-

Yes, coffee drinkers, there is ample scientific evidence that caffeine is physically addictive. However, because the brain-

Taken to excess, caffeine can produce anxiety, restlessness, and increased heart rate, and can disrupt normal sleep patterns. Excessive caffeine use can also contribute to the incidence of sleep disorders, including the NREM parasomnias, like sleepwalking (Cartwright, 2004). Recall that Scott, whose story we told in the Prologue, had been taking caffeine pills for several weeks before his sleepwalking episode. Because Scott never drank coffee or other caffeinated beverages, his caffeine tolerance would have been low. Especially when combined with sleep deprivation, irregular sleep schedules, and high levels of stress—

For some people, a cup of coffee and a cigarette go hand in hand. Cigarettes contain nicotine, another potent and addictive stimulant. Nicotine is found in all tobacco products.

Like caffeine, nicotine increases mental alertness and reduces fatigue or drowsiness. Brain-

When cigarette smoke is inhaled, nicotine reaches the brain in seconds. But over the next hour or two, nicotine’s desired effects diminish. For the addicted person, smoking becomes a finely tuned and regulated behavior that maintains steady brain levels of nicotine. At regular intervals ranging from about 30 to 90 minutes, the smoker lights up, avoiding the withdrawal effects that are starting to occur. For the pack-

A new development in nicotine delivery is “vaping,” or the use of electronic or “e-

The use of e-

People who start smoking or vaping for nicotine’s stimulating properties often continue to avoid the withdrawal symptoms. Along with an intense craving for nicotine, withdrawal symptoms include jumpiness, irritability, tremors, headaches, drowsiness, “brain fog,” and light-

AMPHETAMINES AND COCAINE

Like caffeine and nicotine, amphetamines and cocaine are addictive substances that affect brain dopamine and stimulate brain activity, increasing mental alertness and reducing fatigue (Wang & others, 2015). However, amphetamines and cocaine also elevate mood and produce a sense of euphoria. When abused, both drugs can produce severe psychological and physical problems.

Sometimes called “speed” or “uppers,” amphetamines suppress appetite and were once widely prescribed as diet pills. Benzedrine and Dexedrine are prescription amphetamines. Tolerance to the appetite-

Using any type of amphetamines for an extended period of time is followed by “crashing”—withdrawal symptoms of fatigue, deep sleep, intense mental depression, and increased appetite. This is another example of a drug rebound effect. Users also become psychologically dependent on the drug for the euphoric state, or “rush,” that it produces, especially when injected.

Cocaine is an illegal stimulant derived from the leaves of the coca plant, which is found in South America. (The coca plant is not the source of cocoa or chocolate, which is made from the beans of the cacao tree.) Psychologically, cocaine produces intense euphoria, mental alertness, and self-

The effects of cocaine depend partly on the form in which it is taken. A concentrated form of cocaine, called “crack,” is smoked. When smoked or injected, cocaine reaches the brain in seconds and effects peak in about five minutes. If inhaled or “snorted,” cocaine takes several minutes to be absorbed through the nasal membranes, and peak blood levels are reached in 30 to 60 minutes.

Chronic cocaine use produces a wide range of psychological disorders. Of particular note, the prolonged use of amphetamines or cocaine can result in stimidant-

Methamphetamine, also known as meth, is an illegal drug that can be easily manufactured in home or street laboratories. Providing an intense high that is longer-

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

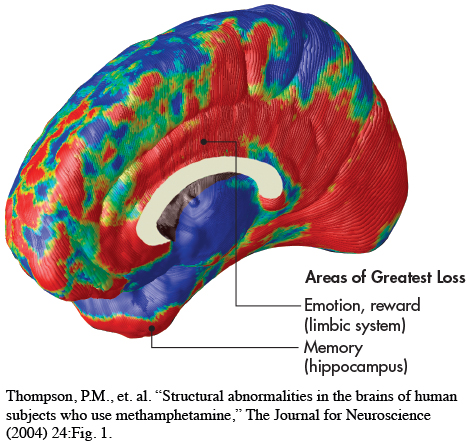

How Methamphetamines Erode the Brain

Researcher Paul Thompson and his colleagues (2004) used MRI scans to compare the brains of chronic methamphetamine users to those of healthy adults. In the composite scan shown here, red indicates areas with tissue loss from 5 to 10 percent. Green indicates 3 to 5 percent tissue loss, and blue indicates relatively intact brain regions. Thompson found that meth abusers experienced up to 10 percent tissue loss in limbic system areas involved in emotion and reward. Significant tissue loss also occurred in hippocampal regions involved in learning and memory.

“We expected some brain changes, but we didn’t expect so much brain tissue to be destroyed,” Thompson said. Not surprisingly, methamphetamine abusers performed more poorly on memory tests as compared to healthy people the same age (Thompson & others, 2004).

Methamphetamine is highly addictive and can cause extensive brain damage and tissue loss, as discussed in the Focus on Neuroscience box, “How Methamphetamines Erode the Brain.” Even after months of abstinence, PET scans of former meth users showed significant reductions in the number of dopamine receptors (Volkow & others, 2001).

Extensive neurological damage, especially to the frontal lobes, adds to the cognitive and social skill deficits that are evident in heavy methamphetamine users (Homer & others, 2008). Depression, emotional instability, and impulsive and violent behavior are also common. Finally, some research suggests that it may take years for the brain to recover from damage caused by methamphetamine abuse (Bamford & others, 2008).

Psychedelic Drugs

MESCALINE, LSD, AND MARIJUANA

The term psychedelic drug was coined in the 1950s to describe a group of drugs that create profound perceptual distortions, alter mood, and affect thinking. Psychedelic literally means “mind manifesting.”

MESCALINE AND LSD

Naturally occurring psychedelic drugs have been used in religious rituals for thousands of years. Mescaline is derived from the peyote cactus. Another psychedelic drug, called psilocybin, is derived from Psilocybe mushrooms, which are sometimes referred to as “magic mushrooms” or “shrooms.”

In contrast to these naturally occurring psychedelics, LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) is a powerful psychedelic drug that was first synthesized in the late 1930s. LSD is far more potent than mescaline or psilocybin. Just 25 micrograms, or one-

LSD and psilocybin are very similar chemically to the neurotransmitter serotonin, which is involved in regulating moods and sensations (see Chapter 2). LSD and psilocybin mimic serotonin in the brain, stimulating serotonin receptor sites in the somatosensory cortex and other brain regions (Carhart-

The effects of a psychedelic experience vary greatly, depending on an individual’s personality, current emotional state, surroundings, and the other people present. A “bad trip” can produce extreme anxiety, panic, and even psychotic episodes. Tolerance to psychedelic drugs may occur after heavy use. However, even heavy users of LSD do not develop physical dependence, nor do they experience withdrawal symptoms if the drug is not taken.

One large-

MARIJUANA

The common hemp plant, Cannabis sativa, is used to make rope and cloth. But when its leaves, stems, flowers, and seeds are dried and crushed, the mixture is called marijuana, one of the most widely used illegal drugs. Marijuana’s active ingredient is the chemical tetrahydrocannabinol, abbreviated THC. When marijuana is smoked, THC reaches the brain in less than 30 seconds. One potent form of marijuana, hashish, is made from the resin of the hemp plant. Hashish is sometimes eaten.

To lump marijuana with the highly psychedelic drugs mescaline and LSD is somewhat misleading. At high doses, marijuana can sometimes produce sensory distortions that resemble a mild psychedelic experience. Low to moderate doses of THC typically produce a sense of well-

In the early 1990s, researchers discovered receptor sites in the brain that are specific for THC. They also discovered a naturally occurring brain chemical, called anandamide, that is structurally similar to THC and that binds to the THC receptors in the brain (Devane & others, 1992; Mechoulam & others, 2014). Anandamide appears to be involved in regulating the transmission of pain signals and may reduce painful sensations. Active ingredients in marijuana have been shown to be involved in several psychological processes, including mood, memory, cognition, appetite, and neurogenesis (see Mechoulam & Parker, 2013).

Marijuana and its active ingredient, THC, have been shown to be helpful in the treatment of pain, epilepsy, hypertension, nausea, glaucoma, arthritis, and asthma (Mechoulam & others, 2014). In cancer patients, THC can prevent the nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy.

On the negative side, marijuana interferes with muscle coordination and perception and may impair driving ability. When marijuana and alcohol use are combined, marijuana’s effects are intensified—

Most marijuana users do not develop physical dependence. Chronic users of high doses can develop some tolerance to THC and may experience withdrawal symptoms when its use is discontinued (Budney & others, 2007; Nocon & others, 2006). Such symptoms include irritability, restlessness, insomnia, tremors, and decreased appetite.

Designer “Club” Drugs

ECSTASY AND THE DISSOCIATIVE ANESTHETIC DRUGS

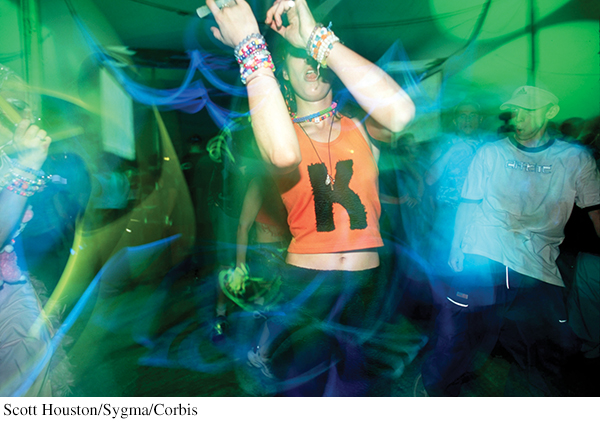

Some drugs don’t fit into neat categories. The “club drugs” are a loose collection of psychoactive drugs that are popular at dance clubs, parties, and the all-

The initials MDMA stand for the long chemical name of the quintessential club drug better known as ecstasy. At low doses, MDMA acts as a stimulant, but at high doses it has mild psychedelic effects. Its popularity, however, results from its emotional effects: Feelings of euphoria, friendliness, and increased well-

The “love drug” effects of ecstasy may result from its unique effect on serotonin in the brain. Along with causing neurons to release serotonin, MDMA also blocks serotonin reuptake, amplifying and prolonging serotonin effects (Braun, 2001). While flooding the brain with serotonin may temporarily enhance feelings of emotional well-

First, the “high” of MDMA is often followed by depression when the drug wears off. More ominously, studies have shown that moderate or heavy use of ecstasy can damage serotonin nerve endings in the brain (Croft & others, 2001; Reneman & others, 2006). Damage to the brain’s serotonin system may account for the depression, anxiety, and sleep and mood disturbances that are associated with long-

Another class of drugs found at dance clubs and raves is the dissociative anesthetics, including phencyclidine, better known as PCP or angel dust, and ketamine (street name Special K). Rather than producing actual hallucinations, PCP and ketamine produce marked feelings of dissociation and depersonalization. Feelings of detachment from reality—

PCP can be eaten, snorted, or injected, but it is most often smoked. The effects are unpredictable, and a PCP trip can last for several days. Some users of PCP report feelings of invulnerability and exaggerated strength. PCP users can become severely disoriented, violent, aggressive, or suicidal. High doses of PCP can cause hyperthermia, convulsions, and death. PCP affects levels of the neurotransmitter glutamate, indirectly stimulating the release of dopamine in the brain. Thus, PCP is highly addictive. Memory problems and depression are common effects of long-

Test your understanding of Psychoactive Drugs with  .

.