Observational Learning

IMITATING THE ACTIONS OF OTHERS

KEY THEME

In observational learning, we learn through watching and imitating the behaviors of others.

KEY QUESTIONS

How did Albert Bandura demonstrate the principles of observational learning?

What four mental processes are involved in observational learning?

How has observational learning been shown in nonhuman animals?

Classical conditioning and operant conditioning emphasize the role of direct experiences in learning, such as directly experiencing a reinforcing or punishing stimulus following a particular behavior. But much human learning occurs indirectly, by watching what others do, then imitating it. In observational learning, learning takes place through observing the actions of others.

Humans develop the capacity to learn through observation at a very early age. Studies of infants, some as young as 2 to 3 days, have shown that they will imitate a variety of actions, including opening their mouths, sticking out their tongues, and making other facial expressions (Leighton & Heyes, 2010). In fact, even newborn infants can imitate adult expressions when they are less than an hour old (Meltzoff, 2007; Meltzoff & Moore, 1989). Toddlers and preschoolers can use observational learning to figure out how to solve complex problems like extracting a toy from a puzzle box (Flynn & Whiten, 2010). The Focus on Neuroscience on page 217 describes new research that may shed some light on the brain mechanisms that support our ability to learn through observation.

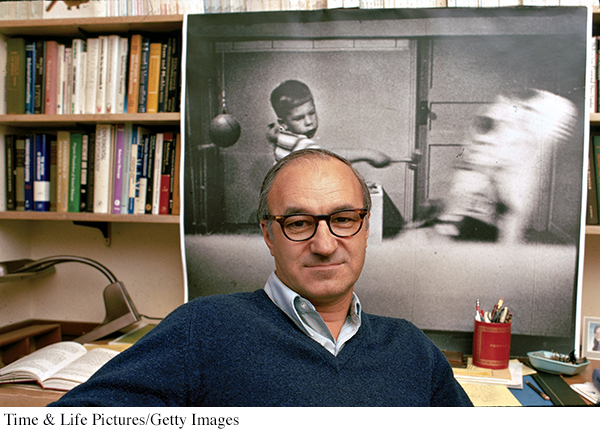

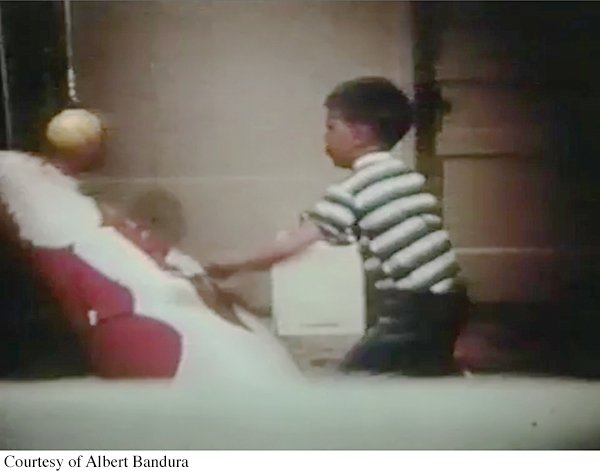

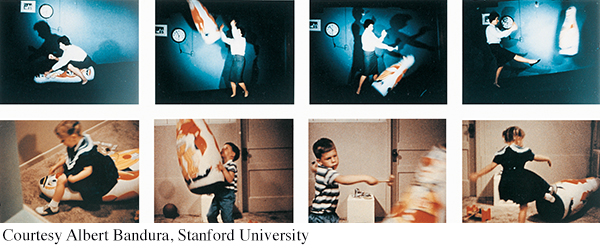

Albert Bandura is the psychologist most strongly identified with observational learning. Bandura (1974) believes that observational learning is the result of cognitive processes that are “actively judgmental and constructive,” not merely “mechanical copying.” To illustrate his theory, let’s consider his famous experiment involving the imitation of aggressive behaviors (Bandura, 1965). In the experiment, four-

However, there were three different versions of the film, each with a different ending. Some children saw the adult reinforced with soft drinks, candy, and snacks after performing the aggressive actions. Other children saw a version in which the aggressive adult was punished for the actions with a scolding and a spanking by another adult. Finally, some children watched a version of the film in which the aggressive adult experienced no consequences.

After seeing the film, each child was allowed to play alone in a room with several toys, including a Bobo doll. The playroom was equipped with a one-

Then Bandura added an interesting twist to the experiment. Each child was asked to show the experimenter what the adult did in the film. For every behavior they could imitate, the child was rewarded with snacks and stickers. Virtually all the children imitated the adult’s behaviors they had observed in the film, including the aggressive behaviors. The particular version of the film the children had seen made no difference.

To view video clips of Bandura’s classic study, try Concept Practice: Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment.

Bandura (1965) explained these results much as Tolman explained latent learning. Reinforcement is not essential for learning to occur. Rather, the expectation of reinforcement affects the performance of what has been learned.

Bandura (1986) suggests that four cognitive processes interact to determine whether imitation will occur. First, you must pay attention to the other person’s behavior. Second, you must remember the other person’s behavior so that you can perform it at a later time. That is, you must form and store a mental representation of the behavior to be imitated. Third, you must be able to transform this mental representation into actions that you are capable of reproducing. These three factors—

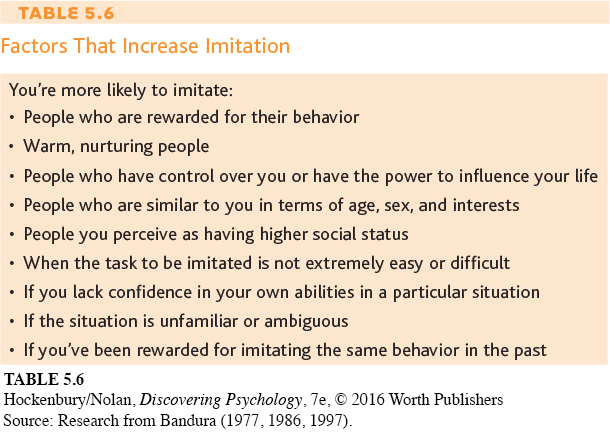

Fourth, there must be some motivation for you to imitate the behavior. This factor is crucial to the actual performance of the learned behavior. You are more likely to imitate a behavior if there is some expectation that doing so will produce reinforcement or reward. Thus, all the children were capable of imitating the adult’s aggressive behavior. But the children who saw the aggressive adult being rewarded were much more likely to imitate the aggressive behavior than were the children who saw the adult punished. Table 5.6 summarizes other factors that increase the likelihood of imitation.

Many nonhuman animals have been shown to learn new behaviors through observation and imitation (Reader & Biro, 2010). The ability to learn a novel behavior through observation has been demonstrated in many different species of animals from hamsters to ring-

Chimpanzees, apes, and other primates are quite adept at learning through observation. Just as with humans, motivational factors influence observational learning. One study involved imitative behavior of free-

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

Mirror Neurons: Imitation in the Brain

Psychologists have only recently begun to understand the neural underpinnings of the human ability to imitate behavior (Glenberg, 2011). The first clue emerged from an accidental discovery in a lab in Palermo, Italy, in the mid-

As one of the wired-

The explanation? Rizzolatti’s team had discovered a new class of specialized neurons, which they dubbed mirror neurons. Mirror neurons are neurons that fire both when an action is performed and when the action is simply perceived (Iacoboni, 2009). It’s important to note that mirror neurons are not a new physical type of neurons. As described in Chapter 2, a mirror neuron is defined by its function, not its physical structure. In effect, these neurons imitate or “mirror” the observed action as though the observer were actually carrying out the action.

A decade of research has shown that mirror neurons do not simply reflect visual processing, but are also involved in mentally representing and interpreting the actions of others (Glenberg, 2011; Michael & others, 2014). For example, Evelyne Kohler and her colleagues (2002) showed that the same neurons that activated when a monkey cracked open a peanut shell also activated when a monkey simply heard a peanut shell breaking.

Following their discovery in the motor cortex, mirror neurons have since been identified in many other brain regions (see Hunter & others, 2013; Iacoboni, 2009). Today, many psychologists use the term mirror neuron system to describe mirroring in the brain. That’s because even simple behaviors and sensations often involve groups of mirror neurons firing together rather than single neurons firing separately (Cattaneo & Rizzolatti, 2009).

Evidence of Human Mirror Neurons

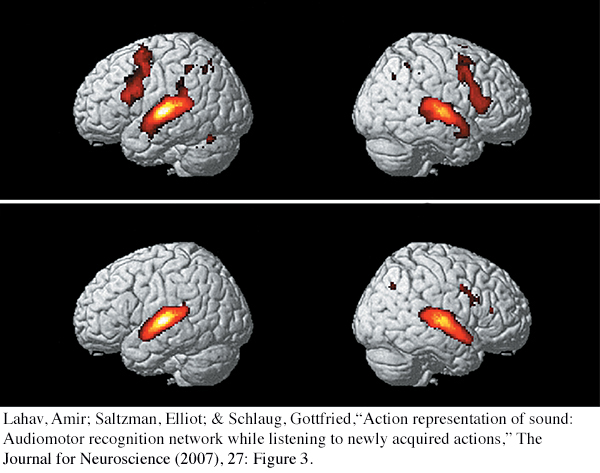

Brain imaging studies like the one illustrated below have provided indirect evidence of mirror neurons in the human brain (see Oberman & Ramachandran, 2007; Slack, 2007). New studies have provided direct evidence for the existence of mirror neurons in humans (see Molenberghs & others, 2012; Mukamel & others, 2010).

Beyond imitation and observational learning, the mirror neuron system may play a role in empathy, language, and social cognition (Gallese & others, 2011; Lago-

As you compare the scans in (a) and (b), notice the extensive activation in motor-

Applications of Observational Learning

Bandura’s finding that children will imitate film footage of aggressive behavior has more than just theoretical importance. One obvious implication has to do with the effects of negative behaviors that are depicted in films and television shows. Is there any evidence that television and other media can increase negative or destructive behaviors in viewers?

One recent study conducted by psychologist Rebecca Collins and her colleagues (2004) examined the impact of television portrayals of sexual activity on the behavior of U.S. adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17. Over the two-

What about exposure to more explicit sexual content, such as pornographic or sexually explicit Web sites on the Internet? One study found that adolescents who visited such sites were more likely to have multiple sexual partners and to have used alcohol or drugs during their most recent sexual experience (Braun-

Another important implication of Bandura’s research relates to the effects of media depictions of violence on behavior. In the Critical Thinking box, we take an in-

Given the potential impact of negative media images, let’s look at the flip side. Is there any evidence that television and other media can encourage socially desirable behavior?

Consider the widely viewed MTV reality series, 16 and Pregnant, which features the struggles of pregnant teens and young mothers. Some commentators feared that the show was glamorizing teenage pregnancy. However, researchers Melissa S. Kearney and Phillip B. Levine (2014) found that teen birth rates in areas where the show was aired dropped 5.7 percent in the 18 months after its introduction. They also surveyed Google searches and social media. They found thousands of tweets and large spikes in Google searches for information about birth control shortly after each episode aired. It’s important to note that the study is correlational, so it’s impossible to say that viewing the TV show directly caused a drop in teen pregnancy. However, the findings highlight ways in which media can influence social outcomes in positive ways.

A remarkably effective application of observational learning has been the use of television and radio dramas to promote social change and healthy behaviors in Asia, Latin America, and Africa (Population Communications International, 2004). Pioneered by Mexican television executive Miguel Sabido, the first such attempt was a long-

CRITICAL THINKING

Does Exposure to Media Violence Cause Aggressive Behavior?

Bandura’s early observational learning studies showed preschoolers enthusiastically mimicking the movie actions of an adult pummeling a Bobo doll. His research provided a powerful paradigm to study the effects of “entertainment” violence. Bandura found that observed actions were most likely to be imitated when:

They were performed by a high-

status, attractive model. The model is rewarded for his or her behavior.

The model is not punished for his or her actions.

Over the past five decades, more than 1,000 studies have investigated the relationship between media depictions of violence and increases in aggressive behavior in the real world (see Bushman & Anderson, 2007; Bushman & others, 2014). We’ll highlight some key findings here.

How Prevalent Is Violence in the Media?

An alarming amount of violence is depicted on American television and in movies. On average, American youth witness 1,000 rapes, murders, and assaults on television annually (Parents Television Council, 2007). More troubling, much of the violent behavior is depicted in ways that are known to increase the likelihood of imitation. For example, violent behavior is not punished and is often perpetrated by the “good guys.” The long-

Is Exposure to Media Violence Linked to Aggressive Behavior?

Numerous research studies show that exposure to media violence produces short-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that viewing violent media is not related to aggression?

Reviewing the accumulation of decades of research evidence, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Psychological Association, and the American Medical Association have all issued versions of the following conclusion: “Extensive research evidence indicates that media violence can contribute to aggressive behavior, desensitization to violence, nightmares, and fear of being harmed” (AAP Council on Communications Media, 2009).

What About Violent Video Games?

Many people wonder about the effects of violent digital games, especially “first-

But other researchers strongly disagree with these conclusions (Ferguson & Kilbourn, 2010; Ivory & others, 2015). For example, some researchers have not found an increase in aggression when violent and non-

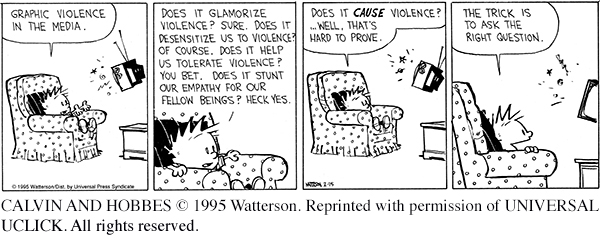

So Does Violent Media Cause Violent Behavior?

Based on their review of the evidence, some psychologists, like Brad Bushman and his colleagues (2009) flatly concluded that “Exposure to violent media increases aggression and violence.” But many other psychologists are more cautious in their conclusions (Elson & Ferguson, 2014a, 2014b; Ivory & others, 2015).

It’s important to note that the vast majority of studies on media violence and aggressive behavior are correlational (Ferguson & Kilbourn, 2009; Savage & Yancey, 2008). As you learned in Chapter 1, correlation does not necessarily imply causation. Even if two factors are strongly correlated, some other variable could be responsible for the association between the two factors. Experimental studies, on the other hand, are designed to demonstrate causality. However, most experimental studies involve artificial measures of aggressive behavior, which may not accurately measure the likelihood that a participant will act aggressively in real life.

Psychologists on both sides of the debate agree on one important point: Violent behavior is a complex phenomenon that is unlikely to have a single cause. They also generally agree that some viewers are highly susceptible to the negative effects of media violence (see Huesmann & others, 2013). Some researchers think that the time has come to go beyond the question of whether media violence causes aggressive behavior and focus instead on investigating the factors that are most likely to be associated with its harmful effects (Feshbach & Tangney, 2008 ; Ferguson & Konijn, 2015).

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

Given the evidence, what conclusions can you draw about the effect of violent media and digital games on aggressive behavior?

Why is it so difficult to design an experimental study that would demonstrate that violent media causes aggressive behavior?

Given the general conclusion that some, but not all, viewers are likely to become more aggressive after viewing violent media, what should be done about media violence?

Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL

UCLICK. All rights reserved.

The serials dramatize the everyday problems people struggle with and model functional strategies and solutions to them. This approach succeeds because it informs, enables, motivates, and guides people for personal and social changes that improve their lives.

—Albert Bandura (2004a)

Since the success of this program, the nonprofit group Population Communications International (2004) has developed over 240 “entertainment-

Education-

Entertainment-

Beyond the effects of media depictions on behavior, observational learning has been applied in a wide variety of settings. The fields of education, vocational and job training, psychotherapy, counseling, and medicine use observational learning to help teach appropriate behaviors.

Test your understanding of Observational Learning with  .

.