Closing Thoughts

One theme throughout this chapter has been the quest to discover general laws of learning that would apply across virtually all species and situations. Watson was convinced that these laws were contained in the principles of classical conditioning. Skinner contended that they were to be found in the principles of operant conditioning. In a sense, they were both right. Thousands of experiments have shown that behavior can be reliably and predictably influenced by classical and operant conditioning procedures. By and large, the general principles of classical and operant conditioning hold up quite well across a wide range of species and situations.

But you’ve also seen that the general principles of classical and operant conditioning are just that—

Another prominent theme has been the adaptive nature of learning. Faced with an ever-

In the final analysis, it’s probably safe to say that the most important consequence of learning is that it promotes the adaptation of many species, including humans, to their unique environments. Were it not for the adaptive nature of learning, Erv would probably have gotten trapped in the attic again!

PSYCH FOR YOUR LIFE

Using Learning Principles to Improve Your Self-

Self-

The Shifting Value of Reinforcers

The key is that the relative value of reinforcers can shift over time (Ainslie, 1975, 1992; Rachlin, 1974, 2000). Let’s use an example to illustrate this principle. Suppose you sign up for an 8:00 A.M. class that meets every Tuesday morning. On Monday night, the short-

Consequently, when your alarm goes off on Tuesday morning, the situation is fundamentally different. The short-

At the moment you make your decision, you choose whichever reinforcer has the greater apparent value to you. At that moment, if the subjective value of the short-

When you understand how the subjective values of reinforcers shift over time, the tendency to impulsively cave in to available short-

Strategy 1: Precommitment

Precommitment involves making an advance commitment to your long-

term goal, one that will be difficult to change when a conflicting reinforcer becomes available (Fujita & Roberts, 2010). In the case of getting to class on time, a precommitment could involve setting multiple alarms and putting them far enough away that you will be forced to get out of bed to shut each of them off. Or you could ask an early- rising friend to call you on the phone and make sure you’re awake. Strategy 2: Self-

Reinforcement Sometimes long-

term goals seem so far away that your sense of potential future reinforcement seems weak compared with immediate reinforcers. One strategy to increase the subjective value of the long- term reinforcer is to use self- reinforcement for current behaviors related to your long- term goal (Fishbach & others, 2010). For example, promise yourself that if you spend two hours studying in the library, you’ll reward yourself by watching a movie. It’s important, however, to reward yourself only after you perform the desired behavior. If you say to yourself, “Rather than study tonight, I’ll go to this party and make up for it by studying tomorrow,” you’ve blown it. You’ve just reinforced yourself for not studying! This would be akin to trying to increase bar-

pressing behavior in a rat by giving the rat a pellet of food before it pressed the bar. Obviously, this contradicts the basic principle of positive reinforcement in which behavior is followed by the reinforcing stimulus. Strategy 3: Stimulus Control

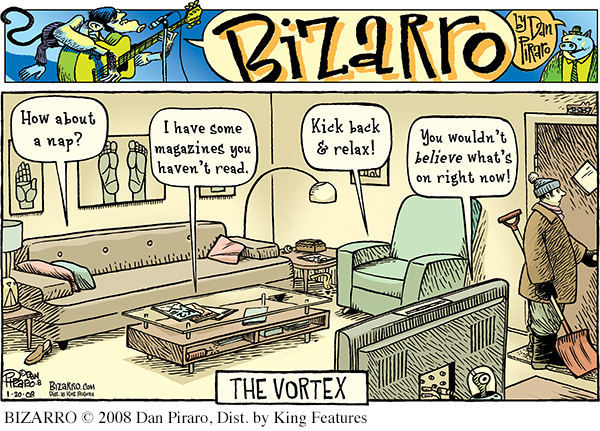

Remember, environmental stimuli can act as discriminative stimuli that “set the occasion” for a particular response (Kruglanski & others, 2010). In effect, the environmental cues that precede a behavior can acquire some control over future occurrences of that behavior. So be aware of the environmental cues that are likely to trigger unwanted behaviors, such as studying in the kitchen (a cue for eating) or in an easy chair in the living room (a cue for watching television). Then replace those cues with others that will help you achieve your long-

term goals. For example, always study in a specific location, whether it’s in the library, in an empty classroom, or at a table or desk in a certain corner of your apartment. Over time, these environmental cues will become associated with the behavior of studying.

BIZARRO © 2008 Dan Piraro, Dist. by King Features

BIZARRO © 2008 Dan Piraro, Dist. by King FeaturesStrategy 4: Focus on the Delayed Reinforcer

The cognitive aspects of learning also play a role in choosing behaviors associated with long-

term reinforcers (Mischel, 1996; Mischel & others, 2004). When faced with a choice between an immediate and a delayed reinforcer, focus your attention on the delayed reinforcer. You’ll be less likely to impulsively choose the short- term reinforcer (Kruglanski & others, 2010). Practically speaking, this means that if your goal is to save money for school, don’t fantasize about a new car or expensive shoes. Focus instead on the delayed reinforcement of achieving your long-

term goal (Kross & others, 2010). Imagine yourself proudly walking across the stage and receiving your college degree. Visualize yourself fulfilling your long- term career goals. The idea in selectively focusing on the delayed reinforcer is to mentally bridge the gap between the present and the ultimate attainment of your future goal. One of our students, a biology major, put a picture of a famous woman biologist next to her desk to help inspire her to study. Strategy 5: Observe Good Role Models

Observational learning is another strategy you can use to improve self-

control (Maddux & others, 2010). In a series of classic studies, psychologist Walter Mischel found that children who observed others choose a delayed reinforcer over an immediate reinforcer were more likely to choose the delayed reinforcer themselves (Kross & others, 2010; Mischel, 1996). So look for good role models. Observing others who are currently behaving in ways that will ultimately help them realize their long- term goals can make it easier for you to do the same.