Retrieval

GETTING INFORMATION FROM LONG-

KEY THEME

Retrieval refers to the process of accessing and retrieving stored information in long-

KEY QUESTIONS

What are retrieval cues and how do they work?

What do tip-

of- the- tongue experiences tell us about the nature of memory? How is retrieval tested, and what is the serial position effect?

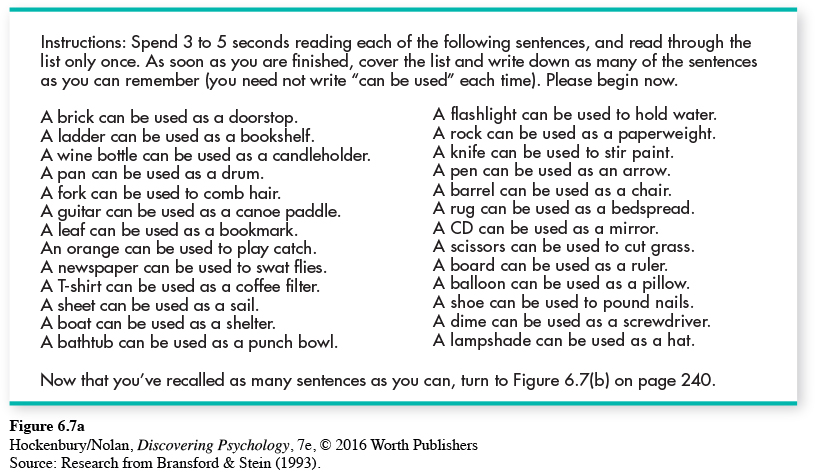

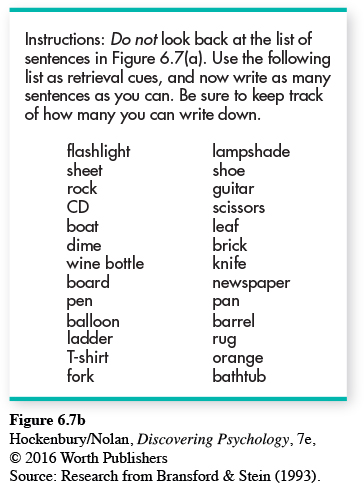

So far, we’ve discussed some of the important factors that affect encoding and storing information in memory. In this section, we will consider factors that influence the retrieval process. Before you read any further, try the demonstration in Figure 6.7. After completing part (a), turn the page and try part (b). We’ll refer to this demonstration throughout this section, so please take a shot at it. After you’ve completed both parts of the demonstration, continue reading.

The Importance of Retrieval Cues

Retrieval refers to the process of accessing, or retrieving, stored information. There’s a vast difference between what is stored in our long-

Let’s compare results. How did you do on the first part of the demonstration, in Figure 6.7(a)? After generating a number of answers, you probably reached a point at which you were unable to remember any more pairs. At that point, you experienced retrieval cue failure, which refers to the inability to recall long-

You should have done much better on the demonstration in Figure 6.7(b). Why the improvement? In part (b) you were presented with retrieval cues that helped you access your stored memories.

This exercise demonstrates the difference between information that is stored in long-

COMMON RETRIEVAL GLITCHES

THE TIP-

Quick—

Did any of these questions leave you feeling as if you knew the answer but just couldn’t quite recall it? If so, you experienced a common, and frustrating, form of retrieval failure, called the tip-

TOT experiences appear to be universal, and the “tongue” metaphor is used to describe the experience in many cultures (Brennen & others, 2007; Schwartz, 1999, 2002). On average, people have about one TOT experience per week, and TOT experiences with particular words tend to recur (D’Angelo & Humphreys, 2015). Although people of all ages experience such word-

When experiencing this sort of retrieval failure, people can almost always dredge up partial responses or related bits of information from their memory. About half the time, people can accurately identify the first letter of the target word and the number of syllables in it. They can also often produce words with similar meanings or sounds. While momentarily frustrating, about 90 percent of TOT experiences are eventually resolved, often within a few minutes.

Tip-

TESTING RETRIEVAL

RECALL, CUED RECALL, AND RECOGNITION

The first part of the demonstration in Figure 6.7 illustrated the use of recall as a strategy to measure memory. Recall, also called free recall, involves producing information using no retrieval cues. This is the memory measure that’s used on essay tests. Other than the essay questions themselves, an essay test provides no additional retrieval cues to help jog your memory.

The second part of the demonstration used a different memory measurement, called cued recall. Cued recall involves remembering an item of information in response to a retrieval cue. Fill-

A third memory measurement is recognition, which involves identifying the correct information from several possible choices. Multiple-

Cued-

THE SERIAL POSITION EFFECT

Notice that the first part of the demonstration in Figure 6.7 did not ask you to recall the sentences in any particular order. Instead, the demonstration tested free recall—

Most people are least likely to recall items from the middle of the list. This pattern of responses is called the serial position effect, which refers to the tendency to retrieve information more easily from the beginning and the end of a list rather than from the middle. There are two parts to the serial position effect. The tendency to recall the first items in a list is called the primacy effect, and the tendency to recall the final items in a list is called the recency effect.

The primacy effect is especially prominent when you have to engage in serial recall, that is, when you need to remember a list of items in their original order. Remembering speeches, telephone numbers, and directions are a few examples of serial recall.

The Encoding Specificity Principle

KEY THEME

According to the encoding specificity principle, re-

KEY QUESTIONS

How can context and mood affect retrieval?

What role does distinctiveness play in retrieval, and how accurate are flashbulb memories?

One of the best ways to increase access to information in memory is to re-

For example, have you ever had trouble remembering some bit of information during a test but immediately recalled it as you entered the library where you normally study? When you intentionally try to remember some bit of information, such as the definition of a term, you often encode much more into memory than just that isolated bit of information. As you study in the library, at some level you’re aware of all kinds of environmental cues. These cues might include the sights, sounds, and aromas within that particular situation. The environmental cues in a particular context can become encoded as part of the unique memories you form while in that context. These same environmental cues can act as retrieval cues to help you access the memories formed in that context.

This particular form of encoding specificity is called the context effect. The context effect is the tendency to remember information more easily when the retrieval occurs in the same setting in which you originally learned the information. Thus, the environmental cues in the library where you normally study act as additional retrieval cues that help jog your memory. Of course, it’s too late to help your test score, but the memory was there.

A different form of encoding specificity is called mood congruence—the idea that a given mood tends to evoke memories that are consistent with that mood. In other words, a specific emotional state can act as a retrieval cue that evokes memories of events involving the same emotion. So, when you’re in a positive mood, you’re more likely to recall positive memories. When you’re feeling blue, you’re more likely to recall negative or unpleasant memories.

Flashbulb Memories

VIVID EVENTS, ACCURATE MEMORIES?

If you rummage around your own memories, you’ll quickly discover that highly unusual, surprising, or even bizarre experiences are easier to retrieve from memory than are routine events (Geraci & Manzano, 2010). Such memories are said to be characterized by a high degree of distinctiveness. That is, the encoded information represents a unique, different, or unusual memory.

Various events can create vivid, distinctive, and long-

Do flashbulb memories literally capture specific details, like the details of a photograph, that are unaffected by the passage of time? Emotionally charged national events have provided a unique opportunity to study flashbulb memories. On September 12, 2001, a day after the World Trade Center attacks, psychologists Jennifer Talarico and David Rubin (2003, 2007) asked university students to complete questionnaires about how they learned about the terrorist attacks. For comparison, students also described an ordinary, everyday event that had recently occurred.

Flashbulb memories are not immune to forgetting, nor are they uncommonly consistent over time. Instead, exaggerated belief in memory’s accuracy at long delays is what may have led to the conviction that flashbulb memories are more accurate than everyday memories.

—Jennifer Talarico and David Rubin (2003)

Over the next year, students were periodically asked to again describe their memories of the 9/11 attacks and of the ordinary event. When the researchers compared these accounts to the original, September 12 reports, they discovered that both the flashbulb and everyday memories had decayed over time, with an increasing number of inconsistent details. But when asked to rate the vividness and accuracy of both memories, only the ratings for the ordinary memory declined. Despite being just as inconsistent as the ordinary memories, the students perceived their flashbulb memories of 9/11 as being more accurate.

A similar pattern was observed in a 10-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that “flashbulb memories,” the vivid memories you form after an important, dramatic event, are no more accurate than other memories?

Although flashbulb memories can seem incredibly vivid, they appear to function just as normal, everyday memories do (Talarico & Rubin, 2009; Hirst & others, 2015). We remember some details, forget some details, and think we remember some details. What does seem to distinguish flashbulb memories from ordinary memories is the high degree of confidence the person has in the accuracy of these memories. But clearly, confidence in a memory is no guarantee of accuracy. We’ll come back to that important point shortly.

Test your understanding of Memory with  .

.