Language and Thought

KEY THEME

Language is a system for combining arbitrary symbols to produce an infinite number of meaningful statements.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the characteristics of language?

What are the effects of bilingualism?

What has research found about the cognitive abilities of nonhuman animals?

The human capacity for language is surely one of the most remarkable of all our cognitive abilities. With little effort, you produce hundreds of new sentences every day. And you’re able to understand the vast majority of the thousands of words contained in this chapter without consulting a dictionary.

Human language has many special qualities—

The Characteristics of Language

The purpose of language is to communicate—

A few symbols may be similar in form to the meaning they signify, such as the English words boom and pop. However, for most words, the connection between the symbol and the meaning is completely arbitrary (Pinker, 1995, 2007). For example, ton is a small word that stands for a vast quantity, whereas nanogram is a large word that stands for a very small quantity. Because the relationship between the symbol and its meaning is arbitrary, language is tremendously flexible (Pinker, 1994, 2007). New words can be invented, such as selfie, podcast, and crowdfund. And the meanings of words can change and evolve, such as spam, troll, and catfish.

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

The Effect of Language on Perception

Professionally, Benjamin Whorf (1897–

Whorf (1956) believed that a person’s language determines the very structure of his or her thought and perception. Your language, he claimed, determines how you perceive and “carve up” the phenomena of your world. He argued that people who speak very different languages have completely different worldviews. More formally, the Whorfian hypothesis is called the linguistic relativity hypothesis—the notion that differences among languages cause differences in the thoughts of their speakers.

To illustrate his hypothesis, Whorf contended that the Eskimos had many different words for “snow.” But English, he pointed out, has only the word snow. According to Whorf (1956):

We have the same word for falling snow, snow on the ground, snow packed hard like ice, slushy snow, wind-

Whorf’s example would be compelling except for one problem: The Eskimos do not have dozens of different words for “snow.” Rather, they have just a few words for “snow” (Pinker, 2007). Beyond that minor sticking point, think carefully about Whorf’s example. Is it really true that English-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that, unlike English speakers, Eskimos have dozens of words for snow?

More generally, people with expertise in a particular area tend to perceive and make finer distinctions than nonexperts do. Experts are also more likely to know the specialized terms that reflect those distinctions (Pinker, 1994, 2007). To the knowledgeable bird-

Despite expert/nonexpert differences in noticing and naming details, we don’t claim that the expert “sees” a different reality than a nonexpert. In other words, our perceptions and thought processes influence the language we use to describe those perceptions (Rosch, 1987; Pinker, 2007). Notice that this conclusion is the exact opposite of the linguistic relativity hypothesis.

Whorf also pointed out that many languages have different color-

Eleanor Rosch set out to answer this question (Heider & Olivier, 1972). The Dani-

Rosch showed Dani speakers a brightly colored chip and then, 30 seconds later, asked them to pick out the color they had seen from an array of other colors. Despite their lack of specific words for the colors they had seen, the Dani did as well as English speakers on the test. The Dani people used the same word to label red and yellow, but they still distinguished between the two. Rosch concluded that the Dani people perceived colors in much the same way as English-

Other research on color-

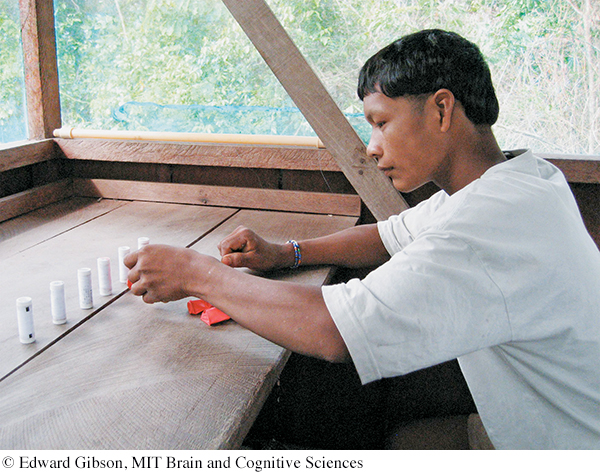

A striking demonstration of the influence of language comes from recent studies of remote indigenous peoples living in the Amazon region of Brazil (Everett, 2005, 2008). The language of the Pirahã people, an isolated tribe of fewer than 200 members, has no words for specific numbers (Frank & others, 2008). Their number words appear to be restricted to words that stand for “few,” “more,” and “many” rather than exact quantities such as “three,” “five,” or “twenty.” Similarly, the Mundurukú language, spoken by another small Amazon tribe, has words only for quantities one through five (Pica & others, 2004). Above that number, they used such expressions as “some,” “many,” or “a small quantity.” In both cases, individuals were unable to complete simple arithmetical tasks (Gordon, 2004).

Such findings do not, by any means, confirm Whorf’s belief that language determines thinking or perception (Deutscher, 2010; Gelman & Gallistel, 2004). Rather, they demonstrate how language categories can affect how individuals think about particular concepts. And most researchers today discuss thinking and language as interacting, each influencing the other and both being influenced by culture (ojalehto & Medin, 2015).

The meaning of these symbols is shared by others who speak the same language. That is, speakers of the same language agree on the connection between the sound and what it symbolizes. Consequently, a foreign language sounds like a stream of meaningless sounds because we do not share the memory of the connection between the arbitrary sounds and the concrete meanings they symbolize.

Further, language is a highly structured system that follows specific rules. Every language has its own unique syntax, or set of rules for combining words. Although you’re usually unaware of these rules as you’re speaking or writing, you immediately notice when a rule has been violated.

The rules of language help determine the meaning that is being communicated. For example, word-

Another important characteristic of language is that it is creative, or generative. That is, you can generate an infinite number of new and different phrases and sentences.

A final important characteristic of human language is called displacement. You can communicate meaningfully about ideas, objects, and activities that are not physically present. You can refer to activities that will take place in the future, that took place in the past, or that will take place only if certain conditions are met (“If I take on extra shifts at work, maybe I can go on spring break with my friends”). You can also carry on a vivid conversation about abstract ideas (“What is justice?”) or strictly imaginary topics (“If you were going to spend a year in a space station orbiting Neptune, what would you bring along?”).

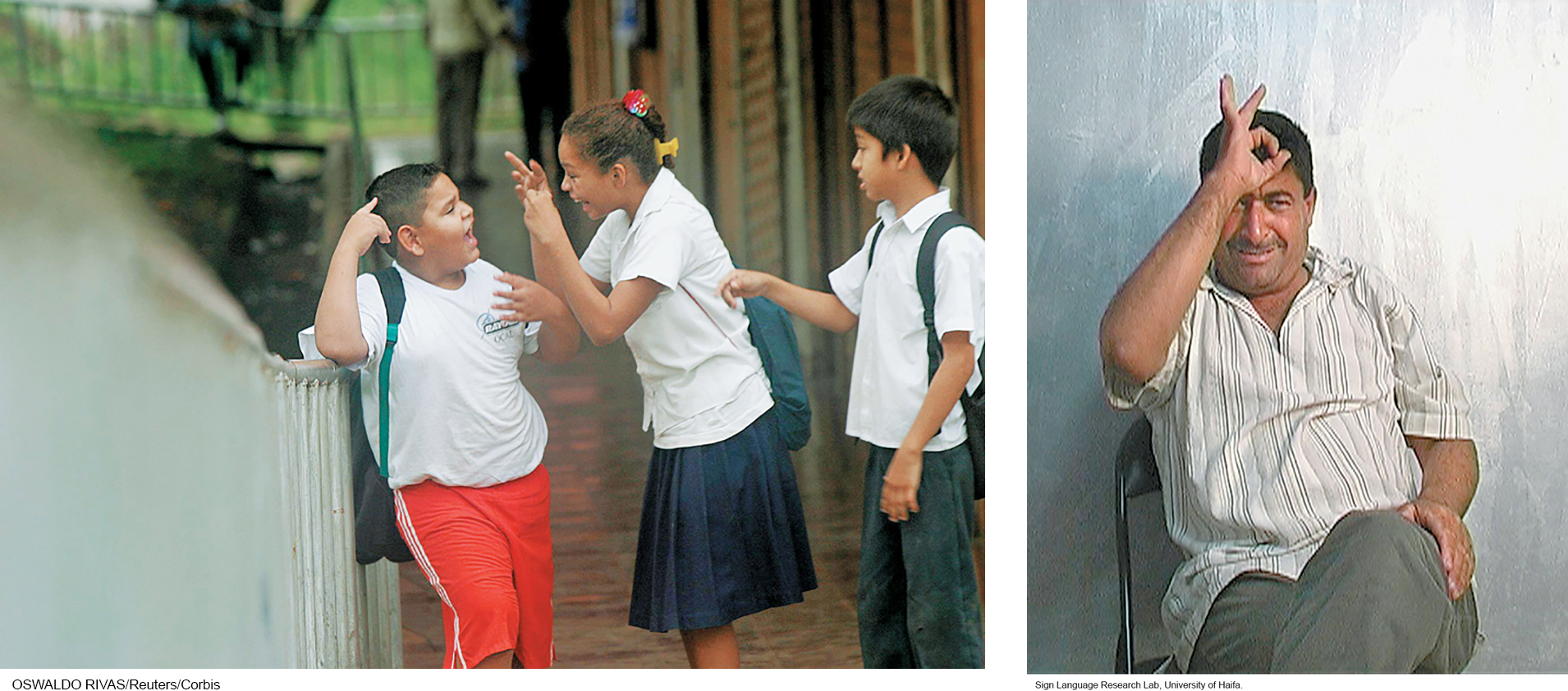

All your cognitive abilities are involved in understanding and producing language. Using learning and memory, you acquire and remember the meaning of words. You interpret the words you hear or read (or see, in the case of American Sign Language and other sign languages) through the use of perception. You use language to help you reason, represent and solve problems, and make decisions (Polk & Newell, 1995).

The Bilingual Mind: Are Two Languages Better Than One?

How many languages can you speak fluently? In many countries, bilingualism, or fluency in two or more languages, is the norm. In fact, estimates are that about two-

At one time, especially in the United States, raising children as bilingual was discouraged. Educators believed that children who simultaneously learned two languages would be confused and not learn either language properly. Such confusion, they believed, could lead to delayed language development, learning problems, and lower intelligence (see Garcia & Náñez, 2011).

But new research has found that bilingualism has many cognitive benefits (Kroll & others, 2014). This is true particularly in the case of balanced proficiency, when speakers are equally proficient in two languages (Garcia & Náñez, 2011). Several studies have found that bilingual speakers are better able to control attention and inhibit distracting information than are monolinguals—

This cognitive flexibility may also have social benefits: Research suggests that bilinguals are better at taking the perspective of others, such as imagining how another person might view a particular situation (Rubio-

Bilingualism also seems to pay off in preserving brain function in old age (Alladi & others, 2013; Bialystok & others, 2012). One clue came from findings in elderly patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, whose symptoms include deterioration in memory and other cognitive functions (Bialystok & others, 2007; Craik & others, 2010). Bilingual patients tended to develop symptoms four to five years later than a control group of patients matched for age, socioeconomic status, and other factors. Like education, exercise, and mental stimulation, speaking two (or more) languages fluently seems to build up what researchers call a cognitive reserve that can help protect against cognitive decline in late adulthood (Bialystok & others, 2012; Costa & Sebastián-

Animal Communication and Cognition

Chimpanzees “chutter” to warn of snakes and “chirp” to let others know that a leopard is nearby. Prairie dogs make different sounds to warn of approaching coyotes, dogs, hawks, and even humans wearing blue shirts versus humans wearing yellow shirts (Slobodchikoff & others, 2009). Even insects have complex communication systems. For example, honeybees perform a “dance” to report information about the distance, location, and quality of a pollen source to their hive mates (J. Riley & others, 2005).

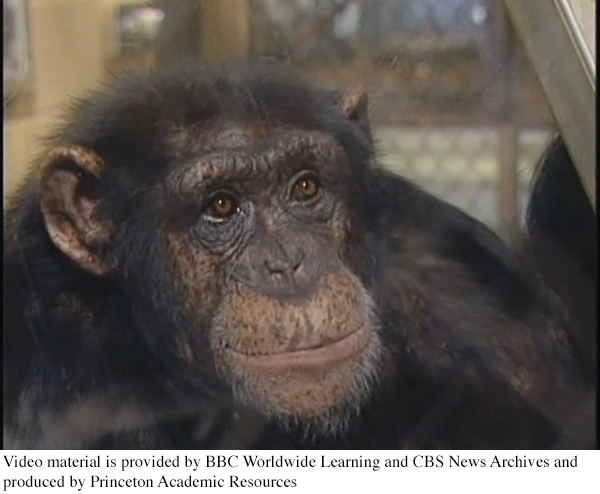

Clearly, animals communicate with one another, but are they capable of mastering language? Some of the most promising results have come from the research of psychologists Sue Savage-

The bonobo named Kanzi was able to learn symbols and also to comprehend spoken English. Altogether, Kanzi understands elementary syntax and more than 500 spoken English words. And, Kanzi can respond to new, complex spoken commands, such as “Put the ball on the pine needles” (Segerdahl & others, 2006). Because these commands are spoken by an assistant out of Kanzi’s view, he cannot be responding to nonverbal cues.

Research evidence suggests that nonprimates also can acquire limited aspects of language. For example, Louis Herman (2002) trained bottle-

Finally, consider Alex, an African gray parrot. Trained by Irene Pepperberg (1993, 2000), Alex could answer spoken questions with spoken words and identify and categorize objects by color, shape, and material (Pepperberg, 2007). Alex also used many simple phrases, such as “Come here” and “Want to go back.”

Going beyond language, psychologists today study many aspects of animal behavior, including memory, problem solving, planning, cooperation, and even deception. Collectively, such research reflects an active area of psychological research that is referred to as animal cognition or comparative cognition (Shettleworth, 2010; Wasserman & Zentall, 2006).

And, rather than focusing on whether nonhuman animals can develop human capabilities, such as language, comparative psychologists today study a wide range of cognitive abilities in many different species (Emery & Clayton, 2009; Santos & Rosati, 2015). For example:

For a fascinating look at a study of animal cognition, try Video Activity: Can Chimpanzees Plan Ahead?

Western scrub jays can, apparently, remember the past and anticipate the future (Clayton & others, 2003). They survive harsh winters by remembering precisely where they stored the food they gathered months earlier (Raby & others, 2007; van der Vaart & others, 2011).

Black-

capped chickadees are able to remember the outcome of a foraging expedition and use that memory to prospectively plan where to seek food in the future (Feeney & others, 2011). Pinyon jays can use logic to determine the social status of other birds by watching how a stranger bird interacts with birds whose social status is already known to them (Paz-

y- Miño & others, 2004). Bengalese finches detect differences in the “syntax” of different bird calls, noticing when the sequencing of phrases differs from songs previously heard (Abe & Watanabe, 2011; Bloomfield & others, 2011).

Dogs are able to distinguish between people who are stingy with food rewards and people who are generous with food rewards (Bray & others, 2014). They remember this information, and later will approach the generous person even if that person clearly has less food to offer than the stingy person.

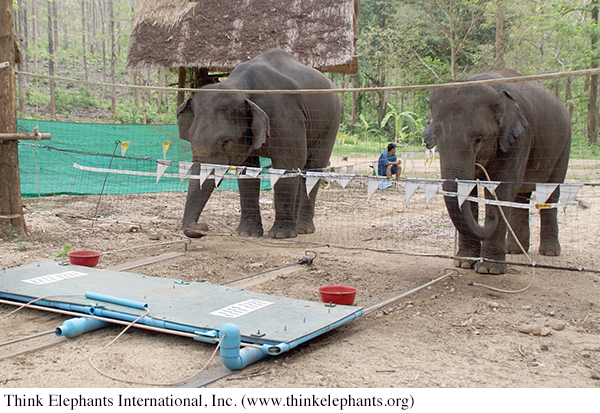

Elephants, highly social animals, seem to understand the nature of cooperation, as reflected in their ability to coordinate their efforts with other elephants in order to reach a food reward (Plotnik & others, 2011).

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that nonhuman animals do not possess high-

Can nonhuman animals “think”? Do they consciously reason? Such questions may be unanswerable (Premack, 2007). More important, many comparative psychologists today take a different approach. Rather than trying to determine whether animals can reason, think, or communicate like humans, these researchers are interested in the specific cognitive capabilities that different species have evolved to best adapt to their ecological niche (de Waal & Ferrari, 2010; Shettleworth, 2010).

Test your understanding of Language and Thought with  .

.