The Nature of Intelligence

KEY THEME

Psychologists do not agree about the basic nature of intelligence, including whether it is a single, general ability and whether it includes skills and talents as well as mental aptitude.

KEY QUESTIONS

What is g, and how did Spearman and Thurstone view intelligence?

What is Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences?

What is Sternberg’s triarchic theory of intelligence?

The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale and the Stanford–

Take another look at the chapter Prologue about Tom and his family. In terms of the type of intelligence that is measured by IQ and other standardized tests, Tom is highly intelligent. But despite his high IQ, Tom can find it extremely difficult to carry out many activities that those with a more “normal” or average intelligence can perform almost effortlessly. Applying for an after-

Theories of Intelligence

Much of the controversy over the definition of intelligence centers on two key issues. First, is intelligence a single, general ability, or is it better described as a cluster of different mental abilities? And second, should the definition of intelligence be restricted to the mental abilities measured by IQ and other intelligence tests? Or should intelligence be defined more broadly?

Although these issues have been debated for more than a century, they are far from being resolved. In this section, we’ll describe the views of four influential psychologists on both issues.

CHARLES SPEARMAN

INTELLIGENCE IS A GENERAL ABILITY

Some psychologists believe that a common factor, or general mental capacity, is at the core of different mental abilities. This approach originated with British psychologist Charles Spearman. Although Spearman agreed that an individual’s scores could vary on tests of different mental abilities, he found that the scores on different tests tended to be similar. That is, people who did well or poorly on a test of one mental ability, such as verbal ability, tended also to do well or poorly on the other tests.

Spearman recognized that particular individuals might excel in specific areas. However, Spearman (1904) believed that a factor he called general intelligence, or the g factor, was responsible for their overall performance on tests of mental ability. Psychologists who follow this approach today think that intelligence can be described as a single measure of general cognitive ability, or g factor (Gottfredson, 1998). Thus, general mental ability could accurately be expressed by a single number, such as the IQ score. Lewis Terman’s approach to measuring and defining intelligence as a single, overall IQ score was in the tradition of Charles Spearman. In terms of Spearman’s model, Tom would undoubtedly score very highly on any test that measured g factor or general intelligence. For example, when he took the SAT as a high school junior, he scored in the top 3 percent in math and received a perfect score on the writing section.

LOUIS L. THURSTONE

NTELLIGENCE IS A CLUSTER OF ABILITIES

Psychologist Louis L. Thurstone disagreed with Spearman’s notion that intelligence is a single, general mental capacity. Instead, Thurstone believed that there were seven different “primary mental abilities,” each a relatively independent element of intelligence. Verbal comprehension, numerical ability, reasoning, and perceptual speed are examples Thurstone gave of independent “primary mental abilities.”

To Thurstone, the so-

HOWARD GARDNER

“MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES”

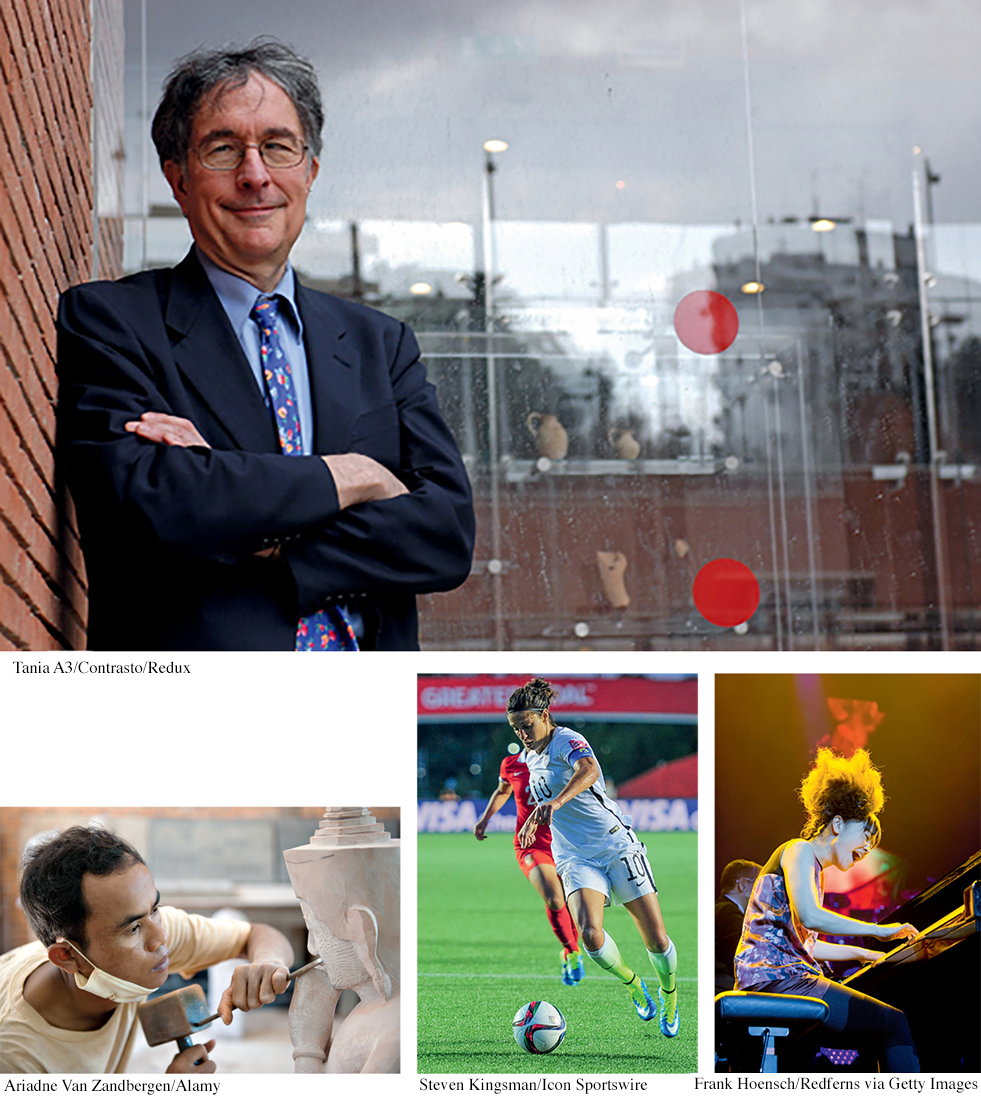

More recently, Howard Gardner has expanded Thurstone’s basic notion of intelligence as different mental abilities that operate independently. However, Gardner has stretched the definition of intelligence (Gardner & Taub, 1999). Rather than analyzing intelligence test results, Gardner (1985, 1993) looked at the kinds of skills and products that are valued in different cultures. He also studied individuals with brain damage, noting that some mental abilities are spared when others are lost. To Gardner, this phenomenon implies that different mental abilities are biologically distinct and controlled by different parts of the brain.

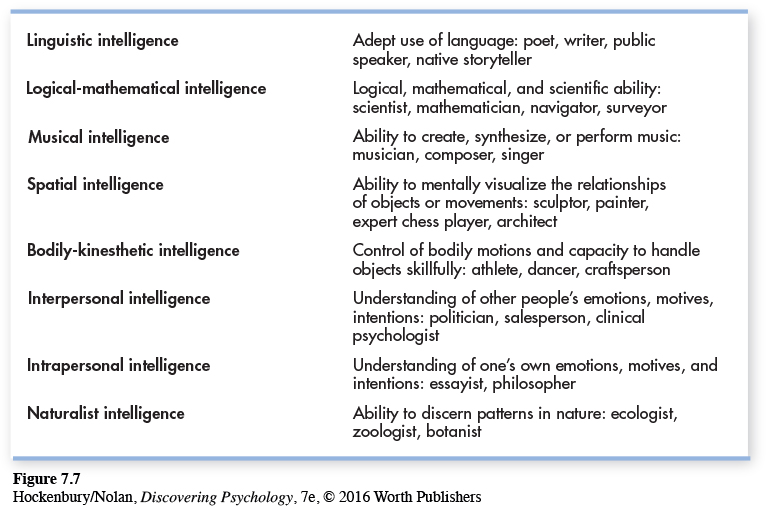

Like Thurstone, Gardner has suggested that such mental abilities are independent of each other and cannot be accurately reflected in a single measure of intelligence. Rather than one intelligence, Gardner (1993, 1998a) believes there are “multiple intelligences.” To Gardner, “an intelligence” is the ability to solve problems, or to create products, that are valued within one or more cultural settings. Thus, he believes that intelligence must be defined within the context of a particular culture (1998b, 2011). Gardner’s theory includes eight distinct, independent intelligences, which are summarized in Figure 7.7. Gardner (2011) has identified a ninth possible intelligence, called existential intelligence, but is awaiting further research before formalizing it as a ninth intelligence. Existential intelligence, or spiritual intelligence, refers to the capacity to reflect upon “ultimate issues,” such as the meaning of life.

According to Gardner’s model of intelligence, everyone has a different pattern of strengths and weaknesses. How would Tom rate? In terms of linguistic, logical-

If I like a song, I like it.

If I don’t, I stop listening.

I really can’t categorize it.

It’s not within my power.

Although lacking musical intelligence probably doesn’t affect your ability to function in our culture, other “intelligences” are much more crucial. Without question, Tom’s biggest shortcoming falls in the realm of interpersonal intelligence. Understanding and relating to other people is extremely difficult for him.

In most cultures, the ability to effectively navigate social situations is crucial to at least one aspect of Wechsler’s definition of intelligence: “the ability to deal effectively with the environment.” Although people with mild symptoms of autism spectrum disorder may not be intellectually disabled, their inability to successfully interact with others leads to even mild forms of autism spectrum disorder being labeled as a disability. However, not everyone agrees with this characterization. Is autism spectrum disorder a disability—

Some of the abilities emphasized by Gardner, such as logical-

ROBERT STERNBERG

THREE FORMS OF INTELLIGENCE

Robert Sternberg (2012, 2014b) agrees with Gardner that intelligence is a much broader quality than is reflected in the narrow range of mental abilities measured by a conventional IQ test. However, Sternberg (1988, 1995) disagrees with Gardner’s notion of multiple, independent intelligences. He believes that some of Gardner’s intelligences are more accurately described as specialized talents, whereas intelligence is a more general quality. Sternberg (1988) points out that you would be able to manage just fine if you were tone-

IN FOCUS

Neurodiversity: Beyond IQ

Can intelligence be summarized by an IQ score? Do standard intelligence tests adequately measure intelligence? Although the questions seem very abstract, their answers can have very real consequences. To give these questions a human face, consider the case of people with autistic symptoms.

Tom, whose story you read in the Prologue, has a very high IQ as measured on standard intelligence tests. However, his inability to navigate social situations makes him less competent in many everyday activities than people with lower IQ scores.

Such difficulties are a hallmark of autism spectrum disorder. The symptoms of autism spectrum disorder cover a broad range, from individuals—

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that most people with an autism spectrum disorder have special mental abilities?

What about the cognitive abilities of people with autism spectrum disorder? At the mild end of the spectrum, people like Tom have normal language development and have an IQ in the normal or even genius range. But it’s a common misconception that most people on the autistic spectrum are autistic savants, like the character “Raymond” played by Dustin Hoffman in the movie Rainman. Autistic savants have some extraordinary talent or ability, usually in a very limited area such as math, music, or art. In reality, only about 1 in 10 autistic people are savants (see Dawson & others, 2008; Treffert & Wallace, 2002). However, fewer than 1 in 2,000 non-

Another common assumption is that most people with autism are intellectually disabled (e.g., Brown & others, 2008). Intellectual disability is a condition in which individuals generally have an IQ of 70 or below and, because of their deficit in mental abilities, are unable to function independently.

Are most people with autism spectrum disorder intellectually disabled? Surveying decades of research, psychologist Meredyth Edelson (2006) found that there was little empirical research to support the claim that the majority of autistic people are intellectually disabled. In fact, because their symptoms vary so much, it’s very difficult to generalize about the cognitive abilities of people with autistic spectrum disorders (Sigman & others, 2006).

It is also hard to accurately measure intelligence in people who lack the ability to communicate or who are not good at social interaction. In children, for example, intelligence is most commonly measured by Wechsler-

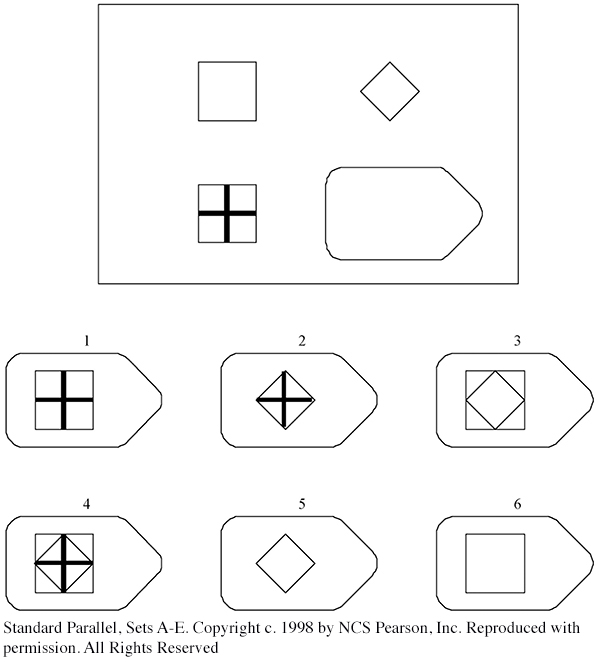

To address this question, Michelle Dawson and her colleagues (2007) used the Raven’s Progressive Matrices Test to measure intelligence in autistic children and adults (see sample items). A nonverbal test of logic and higher-

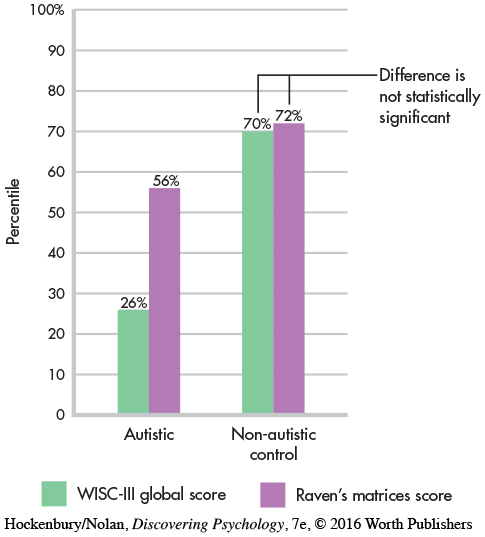

In Dawson’s study, children and adults with autism spectrum disorder took both the Wechsler and the Raven’s tests. How did they do? On average, the autistic children scored at the 26th percentile on the Wechsler—

Did nonautistic participants also show a big difference in scores on the Wechsler versus the Raven’s? No. Members of the nonautistic control groups received very similar scores on the Wechsler and Raven’s tests (see graph).

Many autistics affirm that it would be impossible to segregate the part of them that is autistic. To take away their autism is to take away their personhood. . . . Like their predecessors in human rights, many autistics don’t want to be cured; they want to be accepted. And like other predecessors in civil rights, many autistics don’t want to be required to imitate the majority just to earn their rightful place in society.

—Morton Ann Gernsbacher, 2004

There’s an interesting twist to this story. The lead author, Michelle Dawson—

It was Dawson who came up with the idea for the study (Gerns-

Why are such findings so important? Well, what happens to children who are labeled as “intellectually disabled,” “low-

Today, many researchers, parents, and people “on the spectrum” are embracing a new approach to spectrum disorders. Called neurodiversity, it is the recognition that people with autistic spectrum symptoms process information, communicate, and experience their social and physical environment differently than neurotypical people who don’t have autistic symptoms. Rather than viewing autism as a disorder or disease, advocates of this viewpoint believe that it should be viewed as a disability, like deafness, or a difference, like left-

Neurodiversity advocates do not deny that autistic people need special training and support (Baron-

Disorder, disease, disability, or difference? We’ll give noted researcher Simon Baron-

Autism is both a disability and a difference. We need to find ways of alleviating the disability while respecting and valuing the difference.

Sternberg’s triarchic theory of intelligence emphasizes both the universal aspects of intelligent behavior and the importance of adapting to a particular social and cultural environment. More specifically, Sternberg (1997, 2012) has proposed a different conception of intelligence, which he calls successful intelligence. Successful intelligence involves three distinct types of mental abilities: analytic, creative, and practical.

Analytic intelligence refers to the mental processes used in learning how to solve problems, such as picking a problem-

Creative intelligence is the ability to deal with novel situations by drawing on existing skills and knowledge. The intelligent person effectively draws on past experiences to cope with new situations, which often involves finding an unusual way to relate old information to new. We’ll explore the topic of creativity in more detail in the Psych for Your Life section at the end of the chapter.

Practical intelligence involves the ability to adapt to the environment and often reflects what is commonly called “street smarts.” Sternberg notes that what is required to adapt successfully in one particular situation or culture may be very different from what is needed in another situation or culture. He stresses that the behaviors that reflect practical intelligence can vary depending on the particular situation, environment, or culture.

How would Tom fare by Sternberg’s criteria? Although Tom ranks high in most measures of analytic intelligence, Tom would probably not rank very high in creative or practical intelligence. Successful adaptation involves the flexibility to choose the best problem-

What about practical intelligence? As shown in the Prologue, dealing with the social and academic environment of high school is not easy for Tom. However, many people with autism spectrum disorder find a compatible niche in workplaces in which their ability to focus their attention on a particular technical problem, their preoccupation with details, and other unusual abilities are highly valued, such as in computer programming or engineering firms. In such an environment, their lack of social skills might actually be advantageous (Mayor, 2008). Some companies have figured this out. For example, the German-

The exact nature of intelligence will no doubt be debated for some time. However, the intensity of this debate pales in comparison with the next issue we consider: the origins of intelligence.

The Roles of Genetics and Environment in Determining Intelligence

KEY THEME

Both genes and environment contribute to intelligence, but the relationship is complex.

KEY QUESTIONS

How are twin studies used to measure genetic and environmental influences on intelligence?

What is a heritability estimate, and why can’t it be used to explain differences between groups?

How do social, cultural, and psychological factors affect performance on intelligence tests?

Given that psychologists do not agree on the definition or nature of intelligence, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that psychologists also do not agree on the origin of intelligence. On the surface, the debate comes down to this: Do we essentially inherit our intellectual potential from our parents, grandparents, and great-

Virtually all psychologists agree that both heredity and environment are important in determining intelligence level. Where psychologists disagree is in identifying how much of intelligence is determined by heredity and how much by environment. The implications of this debate have provoked some of the most heated arguments in the history of psychology.

Let’s start with some basic points about the relationship between genes and the environment. It was once believed that genes provided an unchanging, permanent blueprint for human development. As we’ll discuss in Chapter 9, the “genes as blueprint” metaphor has today been replaced by a “genes as data bank” metaphor (Marcus, 2004). It’s now known that environmental factors influence which of the many genes we inherit are “expressed,” meaning actually switched on, or activated. As psychologist Bernard Brown (1999) writes, “Genes are not destiny. There are many places along the gene–

The nature-

—Bernard Brown (1999)

Take the example of height. You inherit a potential range for height, rather than an absolute number of inches. Environmental factors influence how close you come to realizing that genetic potential. If you are healthy and well-

To underscore the interplay between heredity and environment, consider the fact that the average height of Americans has increased by several inches in the past half-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that intelligence is primarily determined by heredity?

The roles of heredity and environment in determining intelligence and personality factors are much more complex than the simple examples of height or eye color (Plomin, 2003; Johnson, 2010). However narrowly intelligence is defined, the genetic range of intellectual potential is influenced by many genes, not by one single gene (Plomin & Spinath, 2004; Nisbett & others, 2012). No one knows how many genes might be involved. Given the complexity of genetic and environmental influences, how do scientists estimate how much of intelligence is due to genetics and how much to environment?

TWIN STUDIES

SORTING OUT THE INFLUENCE OF GENETICS VERSUS ENVIRONMENT

One way this issue has been explored is by comparing the IQ scores of individuals who are genetically related to different degrees. Identical twins share exactly the same genes because they developed from a single fertilized egg that split into two. Hence, any dissimilarities between them must be due to environmental factors rather than hereditary differences. Fraternal twins are like any other pair of siblings because they develop from two different fertilized eggs.

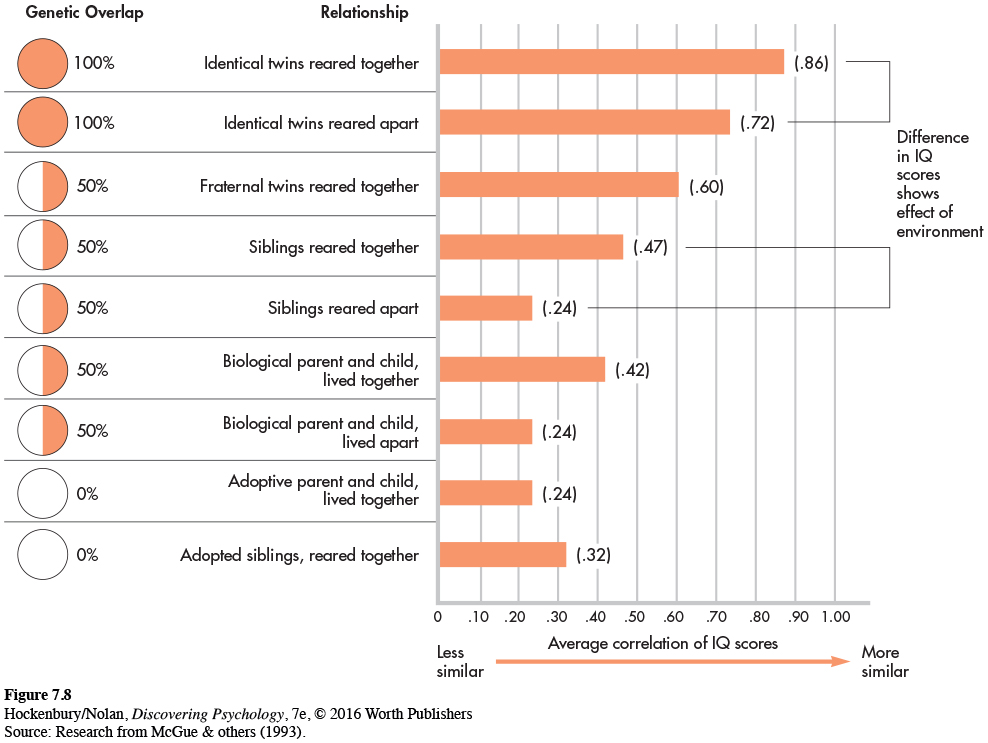

As you can see in Figure 7.8 on the next page, comparing IQ scores in this way shows the effects of both heredity and environment. Identical twins raised together have very similar IQ scores, whereas fraternal twins raised together have IQs that are less similar (Plomin & Spinath, 2004).

However, notice that identical twins raised in separate homes have IQs that are slightly less similar, indicating the effect of different environments. And, although fraternal twins raised together have less similar IQ scores than do identical twins, they show more similarity in IQs than do nontwin siblings. Recall that the degree of genetic relatedness between fraternal twins and nontwin siblings is essentially the same. But because fraternal twins are the same age, their environmental experiences are likely to be more similar than are those of siblings who are of different ages.

Thus, both genetic and environmental influences are important. Genetic influence is shown by the fact that the closer the genetic relationship, the more similar the IQ scores. Environmental influences are demonstrated by two findings: First, two people who are genetically identical but are raised in different homes have different IQ scores. And second, two people who are genetically unrelated but are raised in the same home have IQs that are much more similar than are those of two unrelated people from randomly selected homes.

Using studies based on degree of genetic relatedness and using sophisticated statistical techniques to analyze the data, researchers have scientifically estimated heritability—the percentage of variation within a given population that is due to heredity. The currently accepted heritability estimate is about 50 percent for the general population (see Plomin, 2003; Plomin & Spinath, 2004).

In other words, approximately 50 percent of the difference in IQ scores within a given population is due to genetic factors. But there is disagreement even over this figure, depending on the statistical techniques, data sources used, and age and social class of the population (Deary & others, 2009; Nisbett & others, 2012).

It is important to stress that the 50 percent figure does not apply to a single individual’s IQ score. If Mike’s IQ is 120, it does not mean that 60 IQ points are due to Mike’s environment and 60 points are genetically inherited. Instead, the 50 percent heritability estimate means that approximately 50 percent of the difference in IQ scores within a specific group of people is due to differences in their genetic makeup. More on this key point shortly.

DIFFERENCES WITHIN GROUPS VERSUS DIFFERENCES BETWEEN GROUPS

Some group differences in average IQ scores do exist (Ceci & Williams, 2009). In many societies, including the United States, the average IQ scores of minority groups tend to be lower than the average IQ scores of the dominant or majority groups. There also are differences among countries when national estimates of intelligence are determined (Hunt, 2012). And countries with higher overall intelligence tend to have better economic and health outcomes. The question is how to explain such differences. Heritability cannot be used to explain group differences. Although it is possible to estimate the degree of difference within a specific group that is due to genetics, it makes no sense to apply this estimate to the differences between groups (Rose, 2009). Why? A classic analogy provided by geneticist Richard Lewontin (1970) may help you understand this important point (see Ceci & Williams, 2009).

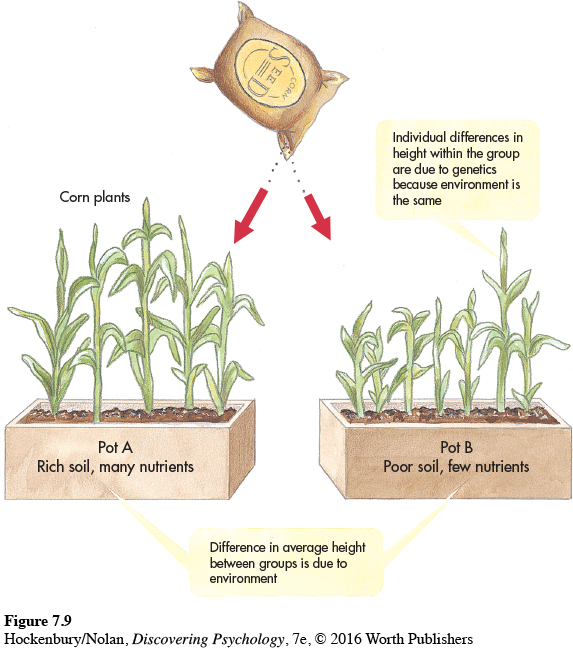

Suppose you have a 50-

Because the seeds are not genetically identical, the plants within group A will vary in height. So will the plants within group B. Given that the environment (the soil) is the same for all the plants in one particular pot, this variation within each group of seeds is completely due to heredity—

However, when we compare the average height of the corn plants in the two pots, pot A’s plants have a higher average height than pot B’s. Can the difference in these average heights be explained in terms of overall genetic differences between the seeds in each pot? No. The overall differences can be attributed to the two different environments, the good soil and the poor soil. In fact, because the environments are so different, it is impossible to estimate what the overall genetic differences are between the two groups of seeds.

Note also that even though, on the average, the plants in pot A are taller than the plants in pot B, some of the plants in pot B are taller than some of the plants in pot A. In other words, the average differences within a group of plants tell us nothing about whether an individual member of that group is likely to be tall or short.

The same point can be extended to the issue of average IQ differences between racial groups. Unless the environmental conditions of two racial groups are virtually identical, it is impossible to estimate the overall genetic differences between the two groups. Even if intelligence were primarily determined by heredity, which is not the case, IQ differences between groups could still be due entirely to the environment.

Other evidence for the importance of the environment in determining IQ scores derives from the improvement in average IQ scores that has occurred in several cultures and countries during the past few generations, a phenomenon called the Flynn Effect (Flynn, 2009; Nisbett & others, 2012).

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

Performing with a Threat in the Air: How Stereotypes Undermine Performance

Your anxiety intensifies as you walk into the testing center. You know how much you’ve prepared for this test. You should feel confident, but you can’t ignore the nagging awareness that not everyone expects you to do well. Can your performance be influenced by your awareness of those expectations?

Standardized testing situations are designed so that everyone is treated as uniformly as possible. Nevertheless, some factors, such as the attitudes and feelings that individuals bring to the testing situation, can’t be standardized. Among the most powerful of these factors are the expectations that you think other people might hold about your performance.

As psychologist Claude Steele (1997) discovered, if those expectations are negative, being aware of that fact can cause you to perform below your actual ability level. Steele coined the term stereotype threat to describe this phenomenon. It’s a response that occurs when members of a group are aware of a negative stereotype about their group and fear they will be judged in terms of that stereotype. Even more unsettling is the fear that you might somehow confirm the stereotype, even when you know that the negative beliefs are false.

For example, one common stereotype is that women perform poorly in math, especially advanced mathematics. Multiple studies have shown that when women are reminded of their gender before taking an advanced mathematics test, their scores are lower than would be expected (see Steele & others, 2007). Even mathematically gifted women show a drop in scores when they are made aware of gender stereotypes (Good & others, 2008; Kiefer & Sekaquaptewa, 2007).

What about positive stereotypes, such as the racial stereotype that Asians are good at advanced mathematics? In a related phenomenon, called stereotype lift, awareness of positive expectations can actually improve performance on tasks (Rydell & others, 2009; Walton & Cohen, 2003).

Psychologist Margaret Shih and her colleagues (1999, 2006) showed how easily gender and racial stereotypes can be manipulated to affect test performance. In one study, mathematically gifted Asian American female college students were randomly assigned to three groups. Group 1 filled out a questionnaire about their Asian background, designed to remind them of their Asian identity. Group 2 filled out a questionnaire designed to remind them of their female identity. Group 3 was the control group and filled out a neutral questionnaire.

The results? The students who were reminded of their racial identity as Asians scored significantly higher on the exam than the students who were reminded of their gender as women. The control group of female students who filled out the neutral questionnaire scored in the middle of the other two groups.

In another study, Shih and her colleagues (2006) assessed the performance of Asian American women on a test of verbal ability, an area in which women are stereotypically expected to excel but Asians are not. In this study, the women scored higher on the verbal test when reminded of their gender, but scored lower on the test when reminded of their race.

Members of virtually any group can experience a decline in performance due to stereotype threat (Schmader & others, 2008). For example:

When a test was described as measuring “problem-

solving skills,” African American students did just as well as white students. But when told that the same test measured “intellectual ability,” African American students scored lower than white students (Aronson & others, 2002; Steele & Aronson, 1995). When reminded of their racial identity, white men did worse on a math test when they thought they were competing with Asian men (Aronson & others, 1999). And, when reminded of their gender, men performed worse than women on a test that was described as measuring “social sensitivity,” but not when the test was described as measuring “complex information processing” (Koenig & Eagly, 2005).

When tests were described as measuring intelligence, Hispanic students performed more poorly than white students (Gonzales & others, 2002); children from a low socioeconomic background performed more poorly than students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds (Croizet & Claire, 1998); and social science majors scored lower than natural science majors (Croizet & others, 2004).

When reminded of the stereotype of the “elderly as forgetful,” older adults scored lower on a memory test than did a matched group not given that reminder (Levy, 1996). Conversely, even taking a memory test or just hearing the instructions for a memory test made older adults feel several years older (Hughes & others, 2013).

How does being reminded of a negative stereotype undermine a person’s performance? First, there’s the fear that you might confirm the stereotype, which creates psychological stress, self-

Hundreds of psychological studies have demonstrated that individual performance on tests—

How can stereotype threat be counteracted? Some research has shown that simply being aware of how stereotype threat can affect your performance helps minimize its negative effects (Johns & others, 2005, 2008; Nadler & Clark, 2011). Reminding yourself of positive aspects of your social identity, such as your identity as a college student, can boost performance (Shih & others, 2012). Also effective are self-

—Claude Steele (1997)

Surveying intelligence test scores around the world, James R. Flynn found that 14 nations showed significant gains in average IQ scores in just one generation (Flynn, 1994, 1999). Subsequent research by Flynn and other researchers documented similar gains in IQ scores in over 30 different countries worldwide (Flynn, 2009). The average IQ score in the United States has also steadily increased over the past century (Flynn, 2007a, 2007b; Weiss, 2010). Such changes in a population can be accounted for only by environmental changes because the amount of time involved is far too short for genetically influenced changes to have occurred.

Cross-Cultural Studies of Group Discrimination and IQ Differences

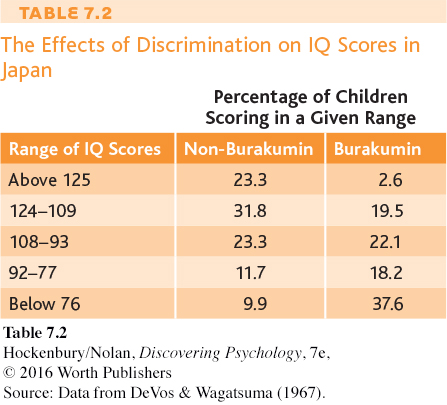

The effect of social discrimination on intelligence test scores has been shown in numerous cross-

Take the case of the Burakumin people of Japan. Americans typically think of Japan as relatively homogeneous, and indeed the Burakumin are not racially different from other Japanese. They look the same and speak the same language. However, the Burakumin are the descendants of an outcast group that for generations worked as tanners and butchers. Because they handled dead bodies and killed animals, the Burakumin were long considered unclean and unfit for social contact. For centuries, they were forced to live in isolated enclaves, apart from the rest of Japanese society (DeVos, 1992; DeVos & Wagatsuma, 1967).

Today, there are about 3 million Burakumin in Japan. Although the Burakumin were legally emancipated from their outcast status many years ago, substantial social discrimination against them persists (Ikeda, 2001; Payton, 1992). Because there is no way to tell if a Japanese citizen is of Burakumin descent, there are dozens of private detective agencies in Tokyo and other Japanese cities that openly specialize in tracking Burakumin who are trying to “pass” and hide their background from employers or prospective marriage partners.

The Burakumin are the poorest people in Japan. They are only half as likely as other Japanese to graduate from high school or attend college. Although there are no racial differences between the Burakumin and the other Japanese, the average IQ scores of the Burakumin are well below those of other Japanese. As shown in Table 7.2, their average IQ scores are about 10 to 15 points below those of mainstream Japanese. But, when Burakumin families immigrate to the United States, they are treated like any other Japanese. The children do just as well in school—

Of course, Japan is not the only society that discriminates against a particular social group. Many societies discriminate against specific minority groups, such as the Harijans in India (formerly called the untouchables), West Indians in Great Britain, Maoris in New Zealand, and Jews of non-

Children belonging to these minority groups score 10 to 15 points lower on intelligence tests than do children belonging to the dominant group in their societies. Children of the minority groups are often one or two years behind dominant-

ARE IQ TESTS CULTURALLY BIASED?

Another approach to explaining group differences in IQ scores has been to look at cultural bias in the tests themselves. If standardized intelligence tests reflect white, middle-

Researchers have attempted to create tests that are “culture-

Cultural differences may also be involved in test-

Test your understanding of The Nature of Intelligence with  .

.