Psychological Needs as Motivators

KEY THEME

According to the motivation theories of Maslow and of Deci and Ryan, psychological needs must be fulfilled for optimal human functioning.

KEY QUESTIONS

How does Maslow’s hierarchy of needs explain human motivation?

What are some important criticisms of Maslow’s theory?

What are the basic premises of self-

determination theory?

Why did you enroll in college? What motivates you to study long hours for an important exam? To push yourself to achieve a new “personal best” at a favorite sport? Rather than being motivated by a biological need or drive like hunger, such behaviors are more likely motivated by the urge to satisfy psychological needs.

In this section, we’ll first consider two theories that attempt to explain psychological motivation: Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs and the more recently developed self-

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

A major turning point in the discussion of human needs occurred when humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow developed his model of human motivation in the 1940s and 1950s. Maslow acknowledged the importance of biological needs as motivators. But once basic biological needs are satisfied, he believed, “higher” psychological needs emerge to motivate human behavior.

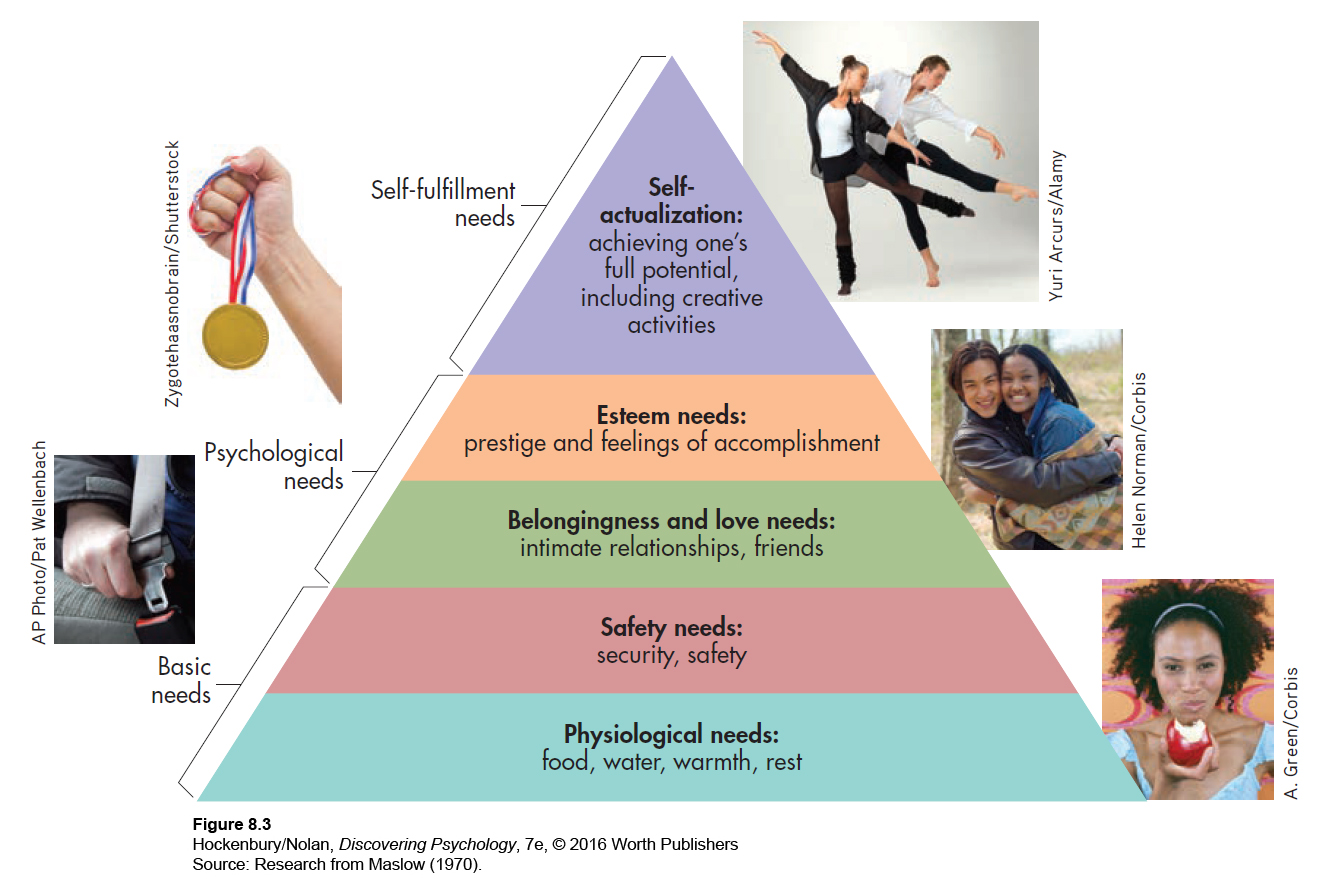

The centerpiece of Maslow’s (1954, 1968) model of motivation was his famous hierarchy of needs, summarized in Figure 8.3. Maslow believed that people are motivated to satisfy the needs at each level of the hierarchy before moving up to the next level. As people progressively move up the hierarchy, they are ultimately motivated by the desire to achieve self-

What exactly is self-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that people need to satisfy basic needs before they can try to achieve higher needs, like artistic expression?

It may be loosely described as the full use and exploitation of talents, capacities, potentialities, etc. Such people seem to be fulfilling themselves and to be doing the best that they are capable of doing. . . . They are people who have developed or are developing to the full stature of which they are capable.

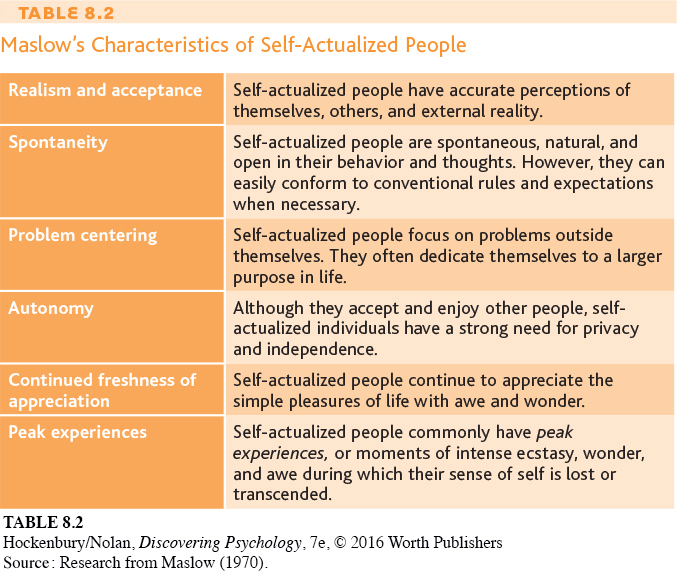

Maslow identified several characteristics of self-

It is quite true that man lives by bread alone—

—Abraham Maslow (1943)

Maslow’s model of motivation generated considerable research, especially during the 1970s and 1980s. Some researchers found support for Maslow’s ideas (see Graham & Balloun, 1973). Others, however, criticized his model on several points (see Fox, 1982; Neher, 1991; Wahba & Bridwell, 1976).

First, Maslow’s notion that we must satisfy needs at one level before moving to the next level has not been supported by empirical research (Sheldon & others, 2001). Second, Maslow’s concept of self-

There is a more important criticism. Despite the claim that self-

Perhaps Maslow’s most important contribution was to encourage psychology to focus on the motivation and development of psychologically healthy people (King, 2008). In advocating that idea, he helped focus attention on psychological needs as motivators.

Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination Theory

Self-

Autonomy—the need to determine, control, and organize one’s own behavior and goals so that they are in harmony with one’s own interests and values.

Competence—the need to learn and master appropriately challenging tasks.

Relatedness—the need to feel attached to others and experience a sense of belongingness, security, and intimacy.

Like Maslow, Deci and Ryan view the need for social relationships as a fundamental psychological motive. The benefits of having strong, positive social relationships are well documented (Leary & Allen, 2011). Another well-

One subtle difference in Maslow’s views compared to those of Deci and Ryan has to do with the definition of autonomy. Deci and Ryan’s definition of autonomy emphasizes the need to feel that your activities are self-

How does a person satisfy the needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness? In a supportive social, psychological, and physical environment, an individual will pursue interests, goals, and relationships that tend to satisfy these psychological needs. In turn, this enhances the person’s psychological growth and intrinsic motivation (Sheldon & Ryan, 2011). Intrinsic motivation is the desire to engage in tasks that the person finds inherently satisfying and enjoyable, novel, or optimally challenging. The doctors, nurses, and other volunteers who traveled to Nepal in the Prologue story displayed intrinsic motivation, taking time away from work and family to contribute their efforts to helping others in a distant land.

In contrast, extrinsic motivation consists of external influences on behavior, such as rewards, social evaluations, rules, and responsibilities. Of course, much of our behavior in daily life is driven by extrinsic motivation (Ryan & La Guardia, 2000). According to SDT, the person who has satisfied the needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness actively internalizes and integrates different external motivators as part of his or her identity and values (Ryan & Deci, 2012). In effect, the person incorporates societal expectations, rules, and regulations as values or rules that he or she personally endorses.

What if one or more of the psychological needs are thwarted by an unfavorable environment, one that is overly challenging, controlling, rejecting, punishing, or even abusive? According to SDT, the person may compensate with substitute needs, defensive behaviors, or maladaptive behaviors. For example, if someone is frustrated in satisfying the need for relatedness, he or she may compensate by chronically seeking the approval of others or by pursuing substitute goals, such as accumulating money or material possessions.

In support of self-

Competence and Achievement Motivation

KEY THEME

Competence and achievement motivation are important psychological motives.

KEY QUESTIONS

How does competence motivation differ from achievement motivation, and how is achievement motivation measured?

What characteristics are associated with a high level of achievement motivation, and how does culture affect achievement motivation?

For more on the historic climb by Pasang and her teammates, visit http://www.k2expedition2014.org/

In self-

A step beyond competence motivation is achievement motivation—the drive to excel, succeed, or outperform others at some task. For example, in the chapter Prologue, Pasang clearly displayed a high level of achievement motivation. Climbing Everest and becoming an internationally certified mountaineering guide are just two examples of Pasang’s drive to achieve. In fact, in late July 2014, Pasang summited K-

In the 1930s, Henry Murray identified 20 fundamental human needs or motives, including achievement motivation. Murray (1938) defined the “need to achieve” as the tendency “to overcome obstacles, to exercise power, [and] to strive to do something difficult as well and as quickly as possible.” Also in the 1930s, Christiana Morgan and Henry Murray (1935) developed a test to measure human motives called the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT). The TAT consists of a series of ambiguous pictures. The person being tested is asked to make up a story about each picture, and the story is then coded for different motivational themes, including achievement. In Chapter 10, on personality, we’ll look at the TAT in more detail.

In the 1950s, David McClelland, John Atkinson, and their colleagues (1953) developed a specific TAT scoring system to measure the need for achievement, often abbreviated nAch. Other researchers developed questionnaire measures of achievement motivation (Spangler, 1992; Ziegler & others, 2010).

Over the next four decades, McClelland and his associates investigated many different aspects of achievement motivation, especially its application in work settings. In cross-

Hundreds of studies have shown that measures of achievement motivation generally correlate well with various areas of success, such as school grades, job performance, and worker output (Senko & others, 2008). This is understandable, since people who score high in achievement motivation expend their greatest efforts when faced with moderately challenging tasks. In striving to achieve the task, they often choose to work long hours and have the capacity to delay gratification and focus on the goal. They also tend to display original thinking, seek expert advice, and value feedback about their performance (McClelland, 1985).

ACHIEVEMENT MOTIVATION AND CULTURE

When it is broadly defined as “the desire for excellence,” achievement motivation is found in many, if not all, cultures. In individualistic cultures, like those that characterize North American and European countries, the need to achieve emphasizes personal, individual success rather than the success of the group. In these cultures, achievement motivation is also closely linked with succeeding in competitive tasks (Markus & others, 2006; Morling & Kitayama, 2008).

In collectivistic cultures, like those of many Asian countries, achievement motivation tends to have a different focus. Instead of being oriented toward the individual, achievement orientation is more socially oriented (Bond, 1986; Kitayama & Park, 2007). For example, students in China felt that it was unacceptable to express pride for personal achievements but that it was acceptable to feel proud of achievements that benefited others (Stipek, 1998). The person strives to achieve not to promote himself or herself but to promote the status or well-

Individuals in collectivistic cultures may persevere or aspire to do well in order to fulfill the expectations of family members and to fit into the larger group. For example, the Japanese student who strives to do well academically is typically not motivated by the desire for personal recognition. Rather, the student’s behavior is more likely to be motivated by the desire to enhance the social standing of his or her family by gaining admission to a top university (Kitayama & Park, 2007).

Test your understanding of Psychological Needs as Motivators with  .

.