Emotion

KEY THEME

Emotions are complex psychological states that serve many functions in human behavior and relationships.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the three components of emotion, and what functions do emotions serve?

How do evolutionary psychologists view emotion?

What are the basic emotions?

The exhilaration of reaching the top of a steep trail. The fear and worry when a friend is late coming in to camp, and the relief and joy when he finally shows up, safe and sound. Emotions color our life from the earliest days of infancy throughout old age. But what, exactly, is emotion?

Emotion is a complex psychological state that involves three distinct components: a subjective experience, a physiological response, and a behavioral or expressive response. How are emotions different from moods? Generally, emotions are intense but rather shortlived. Emotions are also more likely to have a specific cause, to be directed toward some particular object, and to motivate a person to take some sort of action. In contrast, a mood involves a milder emotional state that is more general and pervasive, such as gloominess or contentment. Moods may last for a few hours or even days (Gendolla, 2000).

The Functions of Emotion

Emotional processes are closely tied to motivational processes. Like the word motivation, the root of the word emotion is the Latin word movere, which means “to move.” Often emotions do move us to act. For example, consider the anger that motivates you to seek out a new job when you feel you’ve been treated unfairly by your manager or co-

Emotions help us to set goals, but emotional states can also be goals in themselves. We seek out romantic partners to enjoy the bliss of falling in love or we practice hard to experience the exhilaration of winning a sports competition. And most of us direct our lives so as to maximize the experience of positive emotions and minimize the experience of negative emotions (Gendolla, 2000).

At one time, psychologists considered emotions to be disruptive forces that interfered with rational behavior (Cacioppo & Gardner, 1999). Emotions were thought of as primitive impulses that needed to be suppressed or controlled.

Today, psychologists are much more attuned to the importance of emotions in many different areas of behavior, including rational decision making, purposeful behavior, and setting appropriate goals (Lerner & others, 2015; Mikels & others, 2011). Most of our choices are guided by our feelings, sometimes without our awareness (Kouider & others, 2011). But consider the fate of people who have lost the capacity to feel emotion because of damage to specific brain areas. Despite having an intact ability to reason, such people tend to make disastrous decisions (Damasio, 2004; Rilling & Sanfey, 2011).

Similarly, people who are low in what is termed emotional intelligence may have superior reasoning powers, but they sometimes experience one failure in life after another (Mayer & others, 2004; Van Heck & den Oudsten, 2008). Why? Because they lack the ability to manage their own emotions, comprehend the emotional responses of others, and respond appropriately to the emotions of other people. In contrast, people who are high in emotional intelligence possess these abilities, and they are able to understand and use their emotions (Mayer & others, 2008; Telle & others, 2011).

EVOLUTIONARY EXPLANATIONS OF EMOTION

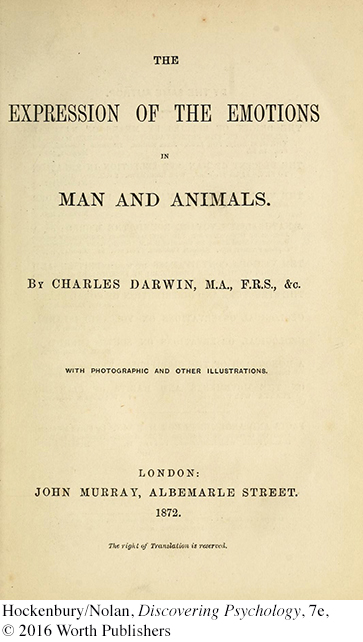

One of the earliest scientists to systematically study emotions was Charles Darwin. Darwin published The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals in 1872, 13 years after he had laid out his general theory of evolution in On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859) and only a year after his book on the evolution of humans, The Descent of Man (1871). Darwin (1872) described the facial expressions, body movements, and postures used to express specific emotions in animals and humans. He argued that emotions reflect evolutionary adaptations to the problems of survival and reproduction.

Like Darwin, today’s evolutionary psychologists believe that emotions are the product of evolution (Damasio & Carvalho, 2013; Cosmides & Tooby, 2013). Emotions help us solve adaptive problems posed by our environment. They “move” us toward potential resources, and they move us away from potential dangers. Fear prompts us to flee an attacker or evade a threat. Anger moves us to turn and fight a rival. Love propels us to seek out a mate and care for our offspring. Disgust prompts us to avoid a sickening stimulus. Obviously, the capacity to feel and be moved by emotion has adaptive value: An organism that is able to quickly respond to rewards or threats is more likely to survive and successfully reproduce.

Darwin (1872) also pointed out that emotional displays serve the important function of informing other organisms about an individual’s internal state. When facing an aggressive rival, the snarl of a baboon signals its readiness to fight. A wolf rolling submissively on its back telegraphs its willingness to back down and avoid a fight.

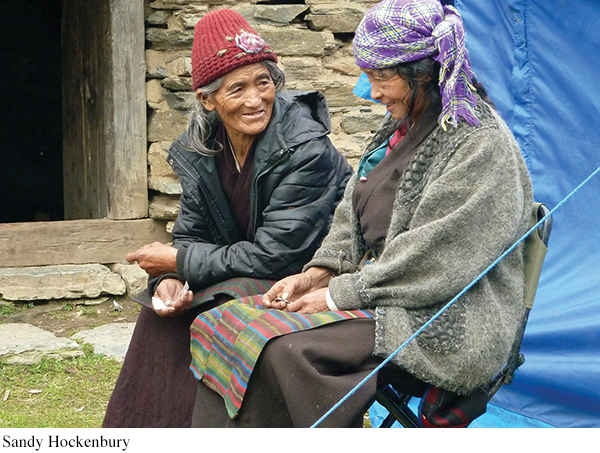

Emotions are also important in situations that go well beyond physical survival. Virtually all human relationships are heavily influenced by emotions. Our emotional experience and expression, as well as our ability to understand the emotions of others, are crucial to the maintenance of social relationships (Reis & others, 2000).

In the next several sections, we’ll consider each of the components of emotion in turn, beginning with the component that is most familiar: the subjective experience of emotion.

The Subjective Experience of Emotion

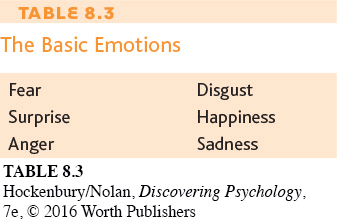

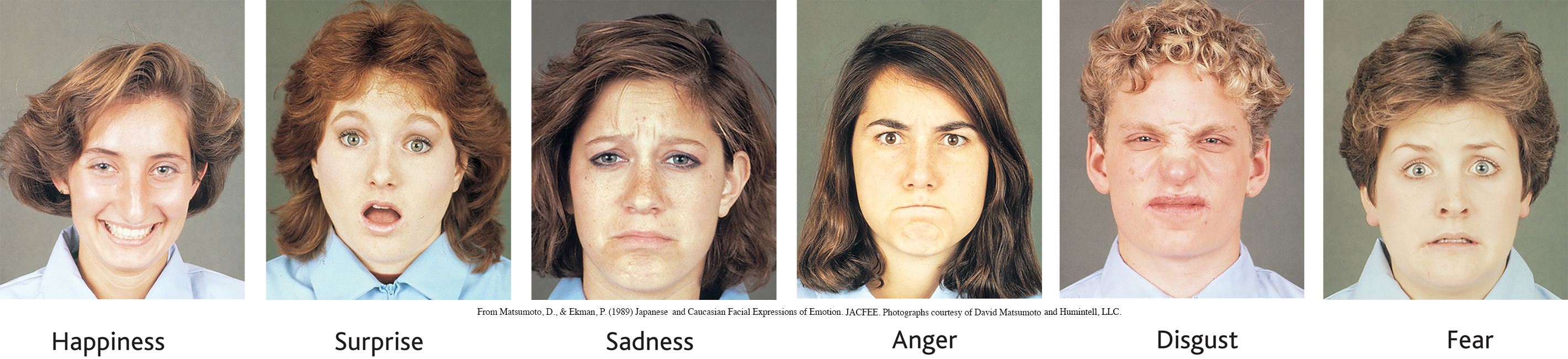

Most emotion researchers today agree that there are a limited number of basic emotions that all humans, in every culture, experience. These basic emotions are thought to be biologically determined, the products of evolution. And what are these basic emotions? As shown in Table 8.3, fear, disgust, surprise, happiness, anger, and sadness are most commonly cited as the basic emotions (Ekman & Cordaro, 2011; Matsumoto & Hwang, 2011a).

Many psychologists contend that each basic emotion represents a sequence of responses that is innate and hard-

Furthermore, psychologists recognize that emotional experience can be complex and multifaceted. People often experience a blend of emotions. In more complex situations, people may experience mixed emotions, in which very different emotions are experienced simultaneously or in rapid succession (Larsen & McGraw, 2011).

CULTURE, GENDER, AND EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE

In diverse cultures, psychologists have found general agreement regarding the subjective experience and meaning of different basic emotions. Canadian psychologist James Russell (1991) compared emotion descriptions by people from several different cultures. He found that emotions were most commonly classified according to two dimensions: (1) the degree to which the emotion is pleasant or unpleasant and (2) the level of activation, or arousal, associated with the emotion. For example, joy and contentment are both pleasant emotions, but joy is associated with a higher degree of activation (Feldman Barrett & Russell, 1999).

While these may be the most fundamental dimensions of emotion, cultural variations in classifying emotions do exist. For example, Hazel Rose Markus and Shinobu Kitayama (1991, 1994) found that Japanese subjects classified emotions in terms of not two but three important dimensions. Along with the pleasantness and activation dimensions, they also categorized emotions along a dimension of interpersonal engagement. This dimension reflects the idea that some emotions result from your connections and interactions with other people (Kitayama & others, 2000). Japanese participants rated anger and shame as being about the same in terms of unpleasantness and activation, but they rated shame as being much higher than anger on the dimension of interpersonal engagement.

Why would the Japanese emphasize interpersonal engagement as a dimension of emotion? Japan is a collectivistic culture, so a person’s identity is seen as interdependent with those of other people, rather than independent, as is characteristic of the more individualistic cultures. Thus, social context is an important part of private emotional experience (Kitayama & Park, 2007).

What about gender differences in emotional experience? Both men and women tend to believe that women are “more emotional” than men (Barrett & Bliss-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that women are more emotional than men?

Rather, the sexes differ in the expression of emotions. In a nutshell, women tend to be more emotionally expressive (Langer, 2010; Keltner & Horberg, 2015). Women tend to be much more at ease expressing their emotions, thinking about emotions, and recalling emotional experiences (Feldman Barrett & others, 2000).

The Neuroscience of Emotion

KEY THEME

Emotions are associated with distinct patterns of responses by the sympathetic nervous system and in the brain.

KEY QUESTIONS

How is the sympathetic nervous system involved in intense emotional responses?

What brain structures are involved in emotional experience, and what neural pathways make up the brain’s fear circuit?

How does the evolutionary perspective explain the dual brain pathways for transmitting fear-

related information?

Psychologists have long studied the physiological aspects of emotion. Early research focused on the autonomic nervous system’s role in triggering physiological arousal. More recently, brain imaging techniques have identified specific brain regions involved in emotions. In this section, we’ll look at both areas of research.

EMOTION AND THE SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

HOT HEADS AND COLD FEET

The pounding heart, rapid breathing, trembling hands and feet, and churning stomach that occur when you experience an intense emotion like fear reflect the activation of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. When you are threatened, the sympathetic nervous system triggers the fight-

Think Like a SCIENTIST

Can you learn to tell when someone is lying? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Lie Detection.

The sympathetic nervous system is also activated by other intense emotions, such as excitement, passionate love, or extreme joy. If you’ve ever ridden an exciting roller coaster, self-

Research has shown that there are differing patterns of physiological arousal for different emotions (Ekman, 2003). In one series of studies, psychologist Robert W. Levenson (1992) found that fear, anger, and sadness are all associated with accelerated heart rate. But comparing anger and fear showed differences that confirm everyday experience. Anger produces greater increases in blood pressure than fear. And while anger produces an increase in skin temperature, fear produces a decrease in skin temperature. Perhaps that’s why when we are angry, we speak of “getting hot under the collar,” and when fearful, we feel clammy and complain of having “cold feet.”

IN FOCUS

Detecting Lies

The polygraph, commonly called a lie detector, doesn’t really detect lies or deception. Rather, a polygraph measures physiological changes associated with emotions like fear, tension, and anxiety. Heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, and other indicators are monitored during a polygraph interview. The polygraph is based on the assumption that lying is accompanied by anxiety, fear, and stress. When people show arousal patterns typically associated with anxiety or fear, lying is inferred (Grubin, 2010; Meijer & Verschuere, 2010).

There are many potential problems with using a polygraph to detect lying. First, there is no unique pattern of physiological arousal associated specifically with lying (Vrij & others, 2010). Second, some people can lie without experiencing anxiety or arousal. This produces a false negative result—

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that polygraphs, or lie detector tests, are a valid way to detect lying?

Finally, interpreting polygraph results can be highly subjective. In one study, polygraph results were compared to later confessions of guilt in criminal cases. Lying was accurately detected by the polygraph examiners at a rate just slightly better than flipping a coin (Phillips, 1999).

In the scientific community, it is generally agreed that polygraphs are not a valid method to detect lies and that their results should not be used as evidence (National Research Council, 2003). Because of the polygraph’s high error rate, many states do not allow polygraph tests as evidence in court. However, the U.S. government uses polygraph testing in several agencies, including the CIA and the Department of Energy (Holden, 2001).

Microexpressions: Fleeting Indicators of Deceit

Emotion researcher Paul Ekman (2003) has found that deception is associated with a variety of nonverbal cues, such as fleeting facial expressions, vocal cues, and nervous body movements. Especially revealing are the fleeting facial expressions, called microexpressions, that last about 1/25 of a second. When people lie and try to control their facial expressions, microexpressions of fear, guilt, or anxiety often “leak” through (Ekman & O’Sullivan, 2006). Even so, no single nonverbal cue indicates that someone is lying, and not all researchers have found evidence that deception is revealed in microexpressions (Vrij, 2015). However, people who are skilled at decoding nonverbal cues—

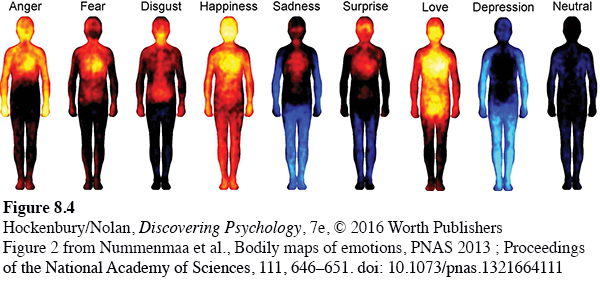

Levenson (1992, 2003) believes that these differing patterns of sympathetic nervous system activation are universal, reflecting biological responses to the basic emotions that are hard-

Broader surveys of different cultures have also demonstrated that the basic emotions are associated with distinct patterns of autonomic nervous system activity (Levenson, 2003; Scherer & Wallbott, 1994). It seems that people in different cultures associate certain patterns of physical sensations with certain emotions. When asked to describe the way that basic emotions such as fear, anger, sadness, and happiness “felt” in the body, Finnish psychologist Lauri Nummenmaa and his colleagues (2014) found a high degree of agreement in participants from Finland, Sweden, and Taiwan (see Figure 8.4).

If you’d like to participate in the experiment, you can try it here: http://becs.aalto.fi/~lnummen/participate.htm

THE EMOTIONAL BRAIN

FEAR AND THE AMYGDALA

Sophisticated brain imaging techniques have led to an explosion of new knowledge about the brain’s role in emotion (Kemp & others, 2015). Of all the emotions, the brain processes involved in fear have been most thoroughly studied. Many brain areas are implicated in emotional responses, but the brain structure called the amygdala has long been known to be especially important. As described in Chapter 2, the amygdala is an almond-

Several studies have shown that the amygdala is a key brain structure in the emotional response of fear in humans (LeDoux, 2007). For example, brain imaging techniques have demonstrated that the amygdala activates when you view threatening or fearful faces, or hear people make nonverbal sounds expressing fear (Morris & others, 1999; Öhman & others, 2007). Even when people simply anticipate a threatening stimulus, the amygdala activates as part of the fear circuit in the brain (Phelps & others, 2001).

In rats, amygdala damage disrupts the neural circuits involved in the fear response. For example, rats with a damaged amygdala can’t be classically conditioned to acquire a fear response (LeDoux, 2007). In humans, damage to the amygdala also disrupts elements of the fear response. For example, people with amygdala damage lose the ability to distinguish between friendly and threatening faces (Adolphs & others, 1998).

Activating the Amygdala: Direct and Indirect Neural Pathways Let’s use an example to show how the amygdala participates in the brain’s fear circuit. Imagine that your sister’s eight-

Even if you don’t know any obnoxious eight-

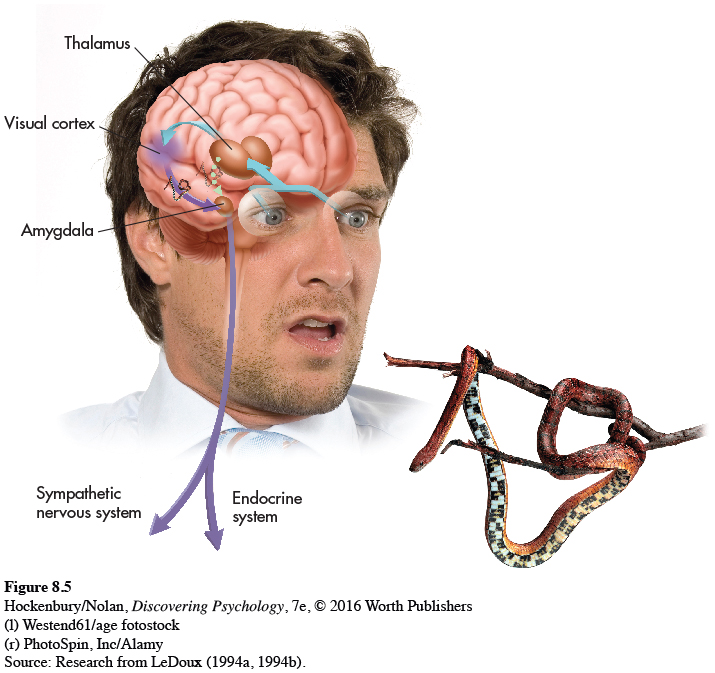

So how can we respond to potentially dangerous stimuli before we’ve had time to think about them? Let’s stay with our example. When you saw the dangling snake, the visual stimulus was first routed to the thalamus (see Figure 8.5). As we explained in Chapter 2, all incoming sensory information, with the exception of olfactory sensations, is processed in the thalamus before being relayed to sensory centers in the cerebral cortex.

(l) Westend61/age fotostock; (r) PhotoSpin, Inc/Alamy

However, the neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux (1996, 2000) discovered that there are two neural pathways for sensory information that project from the thalamus. One leads to the cortex, as previously described, but the other leads directly to the amygdala, bypassing the cortex. When we are faced with a potential threat, sensory information about the threatening stimulus is routed simultaneously along both pathways.

LeDoux (1996) describes the direct thalamus→amygdala pathway as a “shortcut” from the thalamus to the amygdala. This is a “quick-

What happens next? The amygdala sends information along neural pathways that project to other brain regions that make up the rest of the brain’s fear circuit. One pathway leads to an area of the hypothalamus, then on to the medulla at the base of the brain. In combination, the hypothalamus and medulla trigger arousal of the sympathetic nervous system. Another pathway projects from the amygdala to a different hypothalamus area that, in concert with the pituitary gland, triggers the release of stress hormones (LeDoux, 1995, 2000).

The result? You respond instantly to the threat—

LeDoux believes these dual alarm pathways serve several adaptive functions. The direct thalamus→amygdala pathway rapidly triggers an emotional response to threats that, through evolution, we are biologically prepared to fear, such as snakes, snarling animals, or rapidly moving, looming objects. In contrast, the indirect pathway allows more complex stimuli to be evaluated in the cortex before triggering the amygdala’s alarm system. So, for example, the gradually dawning awareness that your job is in jeopardy as your boss starts talking about the need to reduce staff in your department probably has to travel the thalamus→cortex→amygdala pathway before you begin to feel the cold sweat break out on your palms.

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

Emotions and the Brain

Do Different Emotions Activate Different Brain Areas?

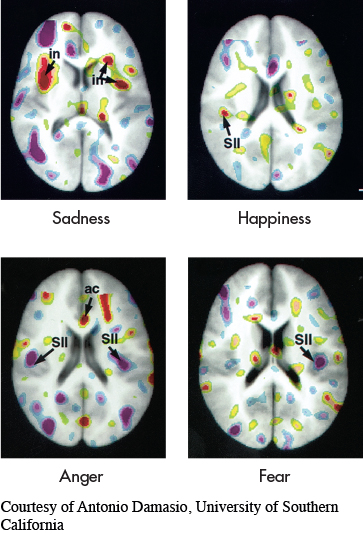

The idea that different combinations of brain regions are activated by different emotions received considerable support in a brain imaging study by neuroscientist Antonio Damasio and his colleagues (2000). In the study, participants were scanned using positron emission tomography (PET) while they recalled emotionally charged memories to generate feelings of sadness, happiness, anger, and fear.

Each of the four PET scans shown here is an averaged composite of all 39 participants in the study. Significant areas of brain activation are indicated in red, while significant areas of deactivation are indicated in purple. Notice that sadness, happiness, anger, and fear each produced a distinct pattern of brain activation and deactivation. These findings confirmed the idea that each emotion involves distinct neural circuits in the brain. Other research has produced similar findings (Dalgleish, 2004; Vytal & Hamann, 2010).

One interesting finding in the Damasio study was that the emotional memory triggered autonomic nervous system activity and physiological arousal before the volunteers signaled that they were subjectively “feeling” the target emotion. Areas of the somatosensory cortex, which processes sensory information from the skin, muscles, and internal organs, were also activated. These sensory signals from the body’s peripheral nervous system contributed to the overall subjective “feeling” of a particular emotion. Remember Damasio’s findings because we’ll refer to this study again when we discuss theories of emotion.

In situations of potential danger, it is clearly advantageous to be able to respond quickly. According to LeDoux (1995, 2000), the direct thalamus→amygdala connection represents an adaptive response that has been hard-

In support of this evolutionary explanation, Swedish psychologist Arne Öhman and his colleagues (Öhman & Mineka, 2001; Schupp & others, 2004) have found that people detect and react more quickly to angry or threatening faces than they do to friendly or neutral faces. Presumably, this reflects the faster processing of threatening stimuli via the direct thalamus→amygdala route (Lundqvist & Öhman, 2005).

The Expression of Emotion

MAKING FACES

KEY THEME

The behavioral components of emotion include facial expressions and nonverbal behavior.

KEY QUESTIONS

What evidence supports the idea that facial expressions for basic emotions are universal?

How does culture affect the behavioral expression of emotion?

How can emotional expression be explained in terms of evolutionary theory?

Every day, we witness the behavioral components of emotions in ourselves and others. We laugh with pleasure, slam a door in frustration, or frown at a clueless remark. But of all the ways that we express and communicate our emotional responses, facial expressions are the most important.

In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Darwin (1872) argued that human emotional expressions are innate and culturally universal. He also noted the continuity of emotional expression between humans and many other species, citing it as evidence of the common evolutionary ancestry of humans and other animals. But do nonhuman animals actually experience emotions? We explore this question in the Critical Thinking box, “Emotion in Nonhuman Animals: Laughing Rats, Silly Elephants, and Smiling Dolphins?”

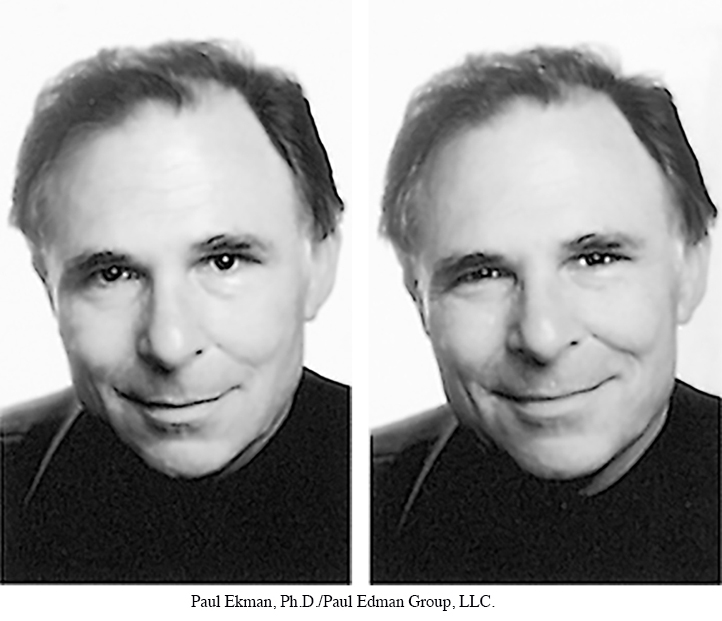

Of course, humans are the animals that exhibit the greatest range of facial expressions. Psychologist Paul Ekman has studied the facial expression of emotions for more than four decades. Ekman (1980) estimates that the human face is capable of creating more than 7,000 different expressions. This enormous flexibility allows us considerable versatility in expressing emotion in all its subtle variations.

To study facial expressions, Ekman and his colleague Wallace Friesen (1978) coded different facial expressions by painstakingly analyzing the facial muscles involved in producing each expression. In doing so, they precisely classified the facial expressions that characterize the basic emotions of happiness, sadness, surprise, fear, anger, and disgust. When shown photographs of these facial expressions, research participants were able to correctly identify the emotion being displayed (Ekman, 1982, 1992, 1993).

Ekman concluded that facial expressions for the basic emotions are innate and probably hard-

CRITICAL THINKING

Emotion in Nonhuman Animals: Laughing Rats, Silly Elephants, and Smiling Dolphins?

Do animals experience emotions? If you’ve ever frolicked with a playful puppy or shared the contagious contentment of a cat purring in your lap, the answer seems obvious. But before you accept that answer, remember that emotion involves three components: physiological arousal, behavioral expression, and subjective experience. In many animals, fear and other “emotional” responses appear to involve physiological and brain processes that are similar to those involved in human emotional experience. In mammals, it’s also easy to observe behavioral responses when an animal is menaced by a predator or by the anger in aggressive displays. But what about subjective experience?

Darwin on Animal Emotions

Charles Darwin never doubted that animals experienced emotions. In his landmark work The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Darwin (1872) contended that differences in emotional experience between nonhuman animals and humans are a matter of degree, not kind. “The lower animals, like man, manifestly feel pleasure and pain, happiness and misery,” he wrote in The Descent of Man in 1871. From Darwin’s perspective, the capacity to experience emotion is yet another evolved trait that humans share with lower animals (Bekoff, 2007).

One problem in establishing whether animals experience emotion is the difficulty of determining the nature of an animal’s subjective experience (Kuczaj, 2013). Even Darwin (1871) readily acknowledged this problem, writing, “Who can say what cows feel, when they surround and stare intently on a dying or dead companion?”

Anthropomorphism: Happy Dolphins?

Despite the problem of knowing just what an animal is feeling, we often think that we do. For example, one reason that dolphins are so appealing is the wide, happy grin they seem to wear. But the dolphin’s “smile” is not a true facial expression—

You also just committed anthropomorphism—you attributed human traits, qualities, or behaviors to a nonhuman animal. The tendency of people to be anthropomorphic is understandable when you consider how extensively most of us were conditioned as children via books, cartoons, and Disney characters to believe that animals are just like people, only with fur or feathers.

From a scientific perspective, anthropomorphism can hinder progress in understanding animal emotions. By assuming that an animal thinks and feels as we do, we run the risk of distorting or obscuring the reality of the animal’s own unique experience (de Waal, 2011; Hauser, 2000). Instead, we must acknowledge that other animals are not happy or sad in the same way that humans subjectively experience happiness or sadness.

Animals clearly demonstrate diverse emotions—

One subjective aspect of the scientific method is how to interpret evidence and data. In the case of the evidence for animal emotions, the scientific debate is far from over. Although the lack of a definitive answer can be frustrating, keep in mind that such scientific debates play an important role in avoiding erroneous conclusions and shaping future research.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

What evidence would lead you to conclude that primates, dolphins, or elephants experience emotions?

Would you accept different evidence to conclude that a 6-

month- old human infant can experience emotions? If so, why? Is it possible to be completely free of anthropomorphic tendencies in studying animal emotions?

To view footage of Paul Ekman and his groundbreaking research on facial expression in Papua New Guinea, go to Video Activity: Emotion and Facial Expression.

CULTURE AND EMOTIONAL EXPRESSION

Facial expressions for the basic emotions seem to be universal across different cultures (Waller & others, 2008). Ekman (1982) and other researchers showed photographs of facial expressions to people in 21 different countries. Despite their different cultural experiences, all the participants identified the emotions being expressed with a high degree of accuracy (see Ekman, 1998). Even the inhabitants of remote, isolated villages in Papua New Guinea, who had never been exposed to movies or other aspects of Western culture, were able to identify the emotions being expressed. Other research has confirmed and extended Ekman’s original findings (see Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002; Frank & Stennett, 2001).

Other aspects of emotional expression, such as tone of voice and nonverbal expression, also seem to be easily understood across widely different cultures. As anyone who has ever been the target of a sarcastic remark is well aware, the human voice very effectively conveys emotional messages. Several studies have found that people from different cultures can accurately identify the emotion being expressed by tone of voice alone, even when the actual words used were unintelligible (Russell & others, 2003; Scherer & others, 2001). Similarly, people from different cultures were able to accurately evaluate the emotional content of video clips depicting an emotional conversation between two people, even though the dialogue was scrambled (Sneddon & others, 2011). And, some body language seems to be universal.

However, some specific nonverbal gestures, which are termed emblems, vary across cultures. For example, shaking your head means “no” in the United States but “yes” in southern India and Bulgaria. Nodding your head means “yes” in the United States, but in Japan it could mean “maybe” or even “no way!”

In many situations, you adjust your emotional expressions to make them appropriate in that particular social context. For example, even if you are deeply angered by your supervisor’s comments at work, you might consciously restrain yourself and maintain a neutral facial expression. How, when, and where we display our emotional expressions are strongly influenced by cultural norms. Cultural differences in the management of facial expressions are called display rules (Ekman & others, 1987; Ambady & others, 2006).

Consider a classic experiment in which a hidden camera recorded the facial expressions of Japanese and Americans as they watched films that showed grisly images of surgery, amputations, and so forth (Ekman & others, 1987; Friesen, 1972). When they watched the films alone, the Japanese and American participants displayed virtually identical facial expressions, grimacing with disgust and distaste at the gruesome scenes. But when a scientist was present while the participants watched the films, the Japanese masked their negative facial expressions of disgust or fear with smiles. Why? In Japan an important display rule is that you should not reveal negative emotions in the presence of an authority figure so as not to offend the higher-

Display rules can also vary for different groups within a given culture. For example, recall our earlier discussion about gender differences in emotional expression. In many cultures, including the United States, women are allowed a wider range of emotional expressiveness and responsiveness than men (Fischer & others, 2004). For example, for men, it’s considered “unmasculine” to be too open in expressing certain emotions, such as sadness ( Johnson & others, 2011). Crying is especially taboo (Vingerhoets & others, 2000).

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that facial expressions, such as smiles, are learned and vary from one culture to another?

So what overall conclusions emerge from the research findings on emotional expressions? First, Paul Ekman and other researchers have amassed considerable evidence that facial expressions for the basic emotions—