Theories of Emotion

EXPLAINING EMOTION

KEY THEME

Emotion theories emphasize different aspects of emotion, but all have influenced the direction of emotion research.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the basic principles and key criticisms of the James–

Lange theory of emotion? How do the facial feedback hypothesis and other contemporary research support aspects of the James–

Lange theory? What are the two-

factor theory and the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, and how do they emphasize cognitive factors in emotion?

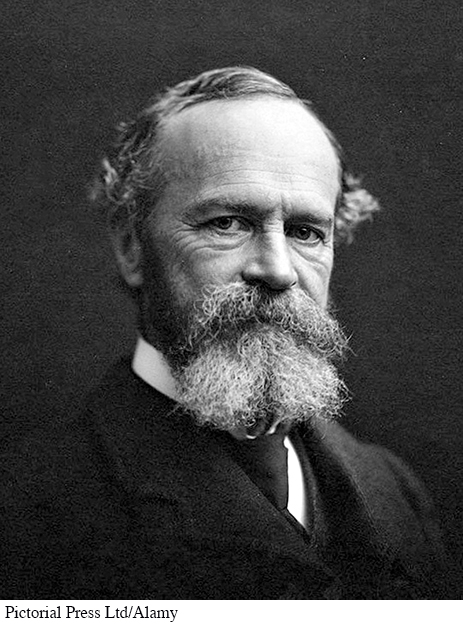

For more than a century, American psychologists have actively debated theories to explain emotion (Manstead, 2015; Reisenzein, 2015). Like many controversies in psychology, the debate helped shape the direction of psychological research. And, in fact, the earliest psychological theory of emotion, proposed by William James more than a century ago, continues to influence psychological research (Dalgleish, 2004; Russell, 2014).

In this section, we’ll look at the most influential theories of emotion. As you’ll see, theories of emotion differ in terms of which component of emotion receives the most emphasis—

The James–Lange Theory of Emotion

Common sense says we lose our fortune, are sorry and weep; we meet a bear, are frightened and run; we are insulted by a rival, are angry and strike. The hypothesis here to be defended says that this order of sequence is incorrect, that the one mental state is not immediately induced by the other, that the bodily manifestations must first be interposed between, and that the more rational statement is that we feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble.

—William James (1894)

DO YOU RUN BECAUSE YOU’RE AFRAID?

OR ARE YOU AFRAID BECAUSE YOU RUN?

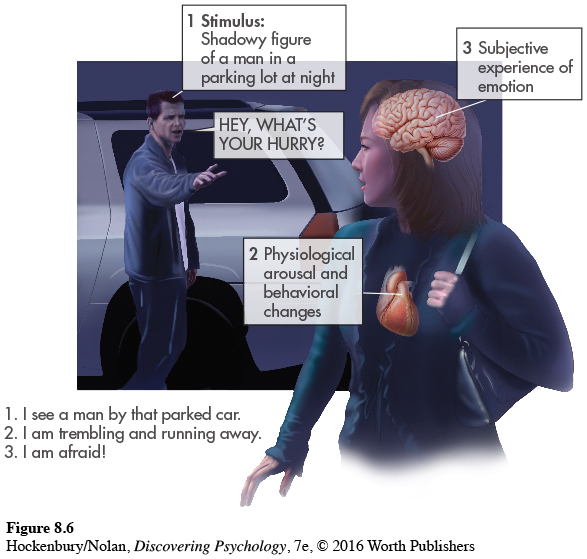

Imagine that you’re walking to your car through the deserted college parking lot late at night. Suddenly, a shadowy figure emerges from behind a parked car. As he starts to move toward you, you walk more quickly. “Hey, what’s your hurry?” he calls out, and he picks up his pace.

Your heart starts pounding as you break into a run. Reaching your car, you fumble with the keys, then jump in and lock the doors. Your hands are trembling so badly you can barely get the key into the ignition, but somehow you manage, and you hit the accelerator, zooming out of the parking lot and onto a main street. Still feeling shaky, you ease off the accelerator pedal a bit, wipe your sweaty palms on your jeans, and will yourself to calm down. After several minutes, you breathe a sigh of relief.

In this example, all three emotion components are clearly present. You experienced a subjective feeling that you labeled as “fear.” You experienced physical arousal—

The common sense view of emotion would suggest that you (1) recognized a threatening situation and (2) reacted by feeling fearful. This subjective experience of fear (3) activated your sympathetic nervous system and (4) triggered fearful behavior. In one of the first psychological theories of emotion, William James (1884) disagreed with this commonsense view, proposing a very different explanation of emotion. Danish psychologist Carl Lange proposed a very similar theory at about the same time (see James, 1894; Lange & James, 1922). Thus, this theory, illustrated in Figure 8.6, is known as the James–

Consider our example again. According to the James–

The James–

Second, Cannon (1927) argued that our emotional reaction to a stimulus is often faster than our physiological reaction. Here’s an example to illustrate this point: Sandy’s car started to slide out of control on a wet road. She felt fear as the car began to skid, but it was only after the car was under control, a few moments later, that her heart began to pound and her hands started to tremble. Cannon correctly noted that it can take several seconds for the physiological changes caused by activation of the sympathetic nervous system to take effect, but the subjective experience of emotion is often virtually instantaneous.

Third, artificially inducing physiological changes does not necessarily produce a related emotional experience. In one early test of the James–

James (1894) also proposed that if a person were cut off from feeling body changes, he would not experience true emotions. If he felt anything, he would experience only intellectualized, or “cold,” emotions. To test this hypothesis, Cannon and his colleagues (1927) disabled the sympathetic nervous system of cats. But the cats still reacted with catlike rage when barking dogs were present: They hissed, growled, and lifted one paw to defend themselves.

What about humans? The sympathetic nervous system operates via the spinal cord. Thus, it made sense to James (1894) that people with spinal cord injuries would experience a decrease in emotional intensity because they would not be aware of physical arousal or other bodily changes.

Once again, however, research has not supported the James–

EVIDENCE SUPPORTING THE JAMES–

On the one hand, you’d think that the James–

For example, look back at the Focus on Neuroscience on page 342 describing the PET scan study by Antonio Damasio and his colleagues (2000). It showed that each of the basic emotions produced a distinct pattern of brain activity, a finding that lends support to the James–

The PET scans showed that areas of the brain’s somatosensory cortex, which processes sensory information from the skin, muscles, and internal organs, were activated during emotional experiences. Interestingly, these internal changes were registered in the somatosensory cortex before the participants reported “feeling” the emotion. Along with demonstrating the importance of internal physiological feedback in emotional experience, Damasio’s study supports another basic premise of the James–

Other contemporary research has supported James’s contention that the perception of internal bodily signals is a fundamental ingredient in the subjective experience of emotion (Dalgleish, 2004; Laird & Lacasse, 2014). For example, in a study by Hugo Critchley and his colleagues (2004), participants who were highly sensitive to their own internal body signals were more likely to experience anxiety and other negative emotions than people who were less sensitive.

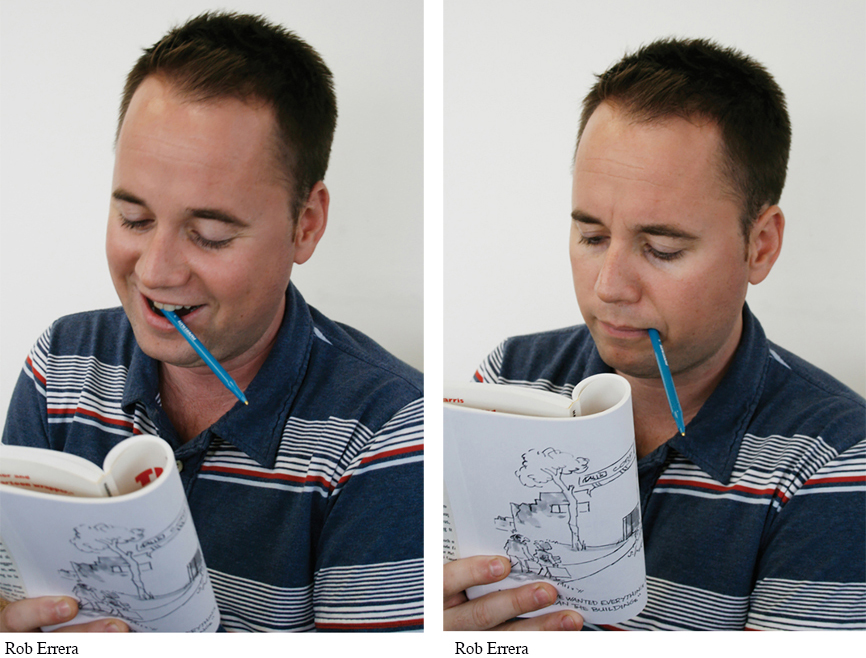

Research on the facial feedback hypothesis also supports the notion that our bodily responses affect our subjective experience. The facial feedback hypothesis states that expressing a specific emotion, especially facially, causes us to subjectively experience that emotion (Soussignan, 2004; Winkielman & others, 2015). Supporting this are studies showing that when people mimic the facial expressions characteristic of a given emotion, such as anger or fear, they tend to report feeling the emotion (Laird & Lacasse, 2014; Schnall & Laird, 2003).

The basic explanation for this phenomenon is that the facial muscles send feedback signals to the brain. In turn, the brain uses this information to activate and regulate emotional experience, intensifying or lessening emotion (Izard, 1990a, 1990b). In line with this explanation, Paul Ekman and Richard Davidson (1993) demonstrated that deliberately creating a “happy” smile produces brain-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that if you “put on a happy face,” you will actually feel happier?

A new wrinkle in facial feedback research comes from the popularity of Botox injections to paralyze selected facial muscles to produce a more youthful appearance. Once paralyzed, the targeted muscles no longer send feedback to the brain. Botox injections can dampen emotional experience, although they don’t appear to eliminate it completely (Davis & others, 2010; Havas & others, 2010). However, an ingenious study by David Deal and Tanya Chartrand (2011) demonstrated that paralyzing facial muscles with Botox may make people less able to recognize emotional expressions in other people. The explanation? We tend to automatically mimic the facial expressions of other people. Although we’re not aware of it, feedback from our facial muscles helps us to better understand their emotional displays.

Collectively, the evidence for the facial feedback hypothesis adds support for aspects of the James–

Cognitive Theories of Emotion

A second theory of emotion, proposed by Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer, was influential for a short time. Schachter and Singer (1962) agreed with James that physiological arousal is a central element in emotion. But they also agreed with Cannon that physiological arousal is very similar for different emotions. Thus, arousal alone would not produce an emotional response.

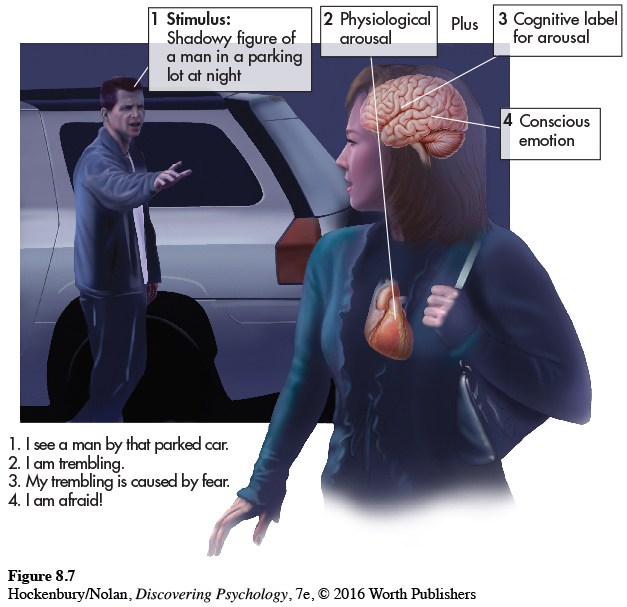

Instead, Schachter and Singer proposed that we cognitively label physiological arousal as a given emotion based on our appraisal of a situation. Thus, according to the two-

Schachter and Singer (1962) tested their theory in a clever, but flawed, experiment. Male volunteers were injected with epinephrine, which produces sympathetic nervous system arousal: accelerated heartbeat, rapid breathing, trembling, and so forth. One group was informed that their symptoms were caused by the injection, but the other group was not given this explanation.

One at a time, the volunteers experienced a situation that was designed to be either irritating or humorous. Schachter and Singer predicted that the subjects who were informed that their physical symptoms were caused by the drug injection would be less likely to attribute their symptoms to an emotion caused by the situation. Conversely, the subjects who were not informed that their physical symptoms were caused by the drug injection would label their symptoms as an emotion produced by the situation.

The results partially supported their predictions. The subjects who were not informed tended to report feeling either happier or angrier than the informed subjects.

Schachter and Singer’s theory inspired a flurry of research. The bottom line of those research efforts? The two-

To help illustrate the final theory of emotion that we’ll consider, let’s go back to the shadowy figure lurking in your college parking lot. Suppose that as the guy called out to you, “Hey, what’s your hurry?” you recognized his voice as that of a good friend. Your emotional reaction, of course, would be very different. This simple observation is the basic premise of the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion.

Developed by Richard Lazarus and Craig Smith (1988), the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion asserts that the most important aspect of an emotional experience is your cognitive interpretation, or appraisal, of the situation or stimulus. That is, emotions result from our appraisal of the personal meaning of events and experiences. Thus, the same situation might elicit very different emotions in different people (Moors, 2009; C. Smith & others, 2006).

So, in the case of the shadowy figure in the parking lot, your relief that you were not on the verge of being attacked by a mugger could quickly turn to another emotion. If it’s a good friend you hadn’t seen for a while, your relief might turn to pleasure, even joy. If it’s someone that you’d prefer to avoid, relief might transform itself into annoyance or even anger.

At first glance, the cognitive appraisal theory and the Schachter–

Some critics of the cognitive appraisal approach objected that emotional reactions to events were virtually instantaneous—

On the other hand, some emotional responses are virtually instantaneous, bypassing conscious consideration. As Joseph LeDoux and other neuroscientists have demonstrated, the human brain can respond to biologically significant threats without involving conscious cognitive processes (Kihlstrom & others, 2000). So at least in some instances, we do seem to feel first and think later.

Test your understanding of Emotion with  .

.