INTRODUCTION:

People Are People

KEY THEME

Developmental psychology is the study of how people change over the lifespan.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the nine basic stages of the lifespan?

What are some of the key themes in developmental psychology?

One way to look at the overall development of your life is to think of your life as a story. You, of course, are the main character. Your life story so far has had a distinct plot, occasional subplots, and a cast of supporting characters, including family, friends, and lovers.

Like every other person’s life story, yours has been influenced by factors beyond your control. One such factor is the unique combination of genes you inherited from your biological mother and father. Another is the historical era during which you grew up. James’s life story, for example, will be shaped by the fact that he is living in an era in which more people are learning about and accepting transgender people. Your individual development has also been shaped by the cultural, social, and family contexts within which you were raised.

The patterns of your life story, and the life stories of countless other people, are the focus of developmental psychology—the study of how people change physically, cognitively, and socially throughout the lifespan. Developmental psychologists investigate the influence of biological, environmental, social, cultural, and behavioral factors on development at every age and stage of life.

The impact of these factors on individual development is greatly influenced by attitudes, perceptions, and personality characteristics. For example, the adjustment to middle school may be a breeze for one child but a nightmare for another. Gender identity, too, can affect individual development, as we saw in James’s story. So, although we are influenced by the events we experience, we also shape the meaning and consequences of those events.

Along with studying common patterns of growth and change, developmental psychologists look at the ways in which people differ in their development and life stories. As we’ll note several times in this chapter, the typical, or “normal,” pattern of development can also vary across cultures (Kagan, 2011; Molitor & Hsu, 2011).

Developmental psychologists use varied research methods, but two research strategies are particularly important in understanding how people develop: longitudinal and cross-

In contrast, research using a cross-

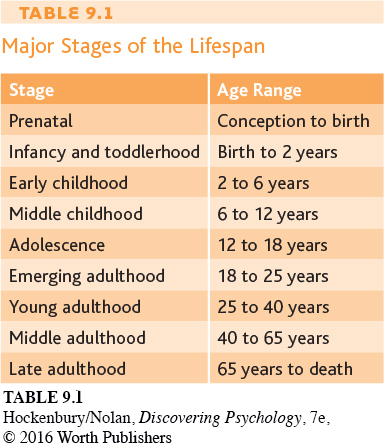

Developmental psychologists often conceptualize the lifespan in terms of basic stages of development (see Table 9.1). Traditionally, the stages of the lifespan are defined by age, which implies that we experience relatively sudden, age-

Still, most of our physical, cognitive, and social changes occur gradually. As we trace the typical course of human development in this chapter, the theme of gradually unfolding changes throughout the ages and stages of life will become more evident. Another important theme in developmental psychology is the interaction between heredity and environment. Traditionally, this was called the nature—