Development During Infancy and Childhood

KEY THEME

Although physically helpless, newborn infants are equipped with reflexes and sensory capabilities that enhance their chances for survival.

KEY QUESTIONS

How do the senses and the brain develop after birth?

What roles do temperament and attachment play in social and personality development?

What are the stages of language development?

The newly born infant enters the world with an impressive array of physical and sensory capabilities. Initially, his behavior is mostly limited to reflexes that enhance his chances for survival. Touching the newborn’s cheek triggers the rooting reflex—the infant turns toward the source of the touch and opens his mouth. Touching the newborn’s lips evokes the sucking reflex. If you put a finger on each of the newborn’s palms, he will respond with the grasping reflex—the baby will grip your fingers so tightly that he can be lifted upright. As motor areas of the infant’s brain develop over the first year of life, the rooting, sucking, and grasping reflexes are replaced by voluntary behaviors.

Anthony Young

The newborn’s senses—

And, newborns quickly learn to differentiate between their mothers and strangers. Within just hours of their birth, newborns display a preference for their mother’s voice and face over that of a stranger (Bushnell, 2001). For their part, mothers become keenly attuned to their infant’s appearance, smell, and even skin texture. Fathers, too, are able to identify their newborn from a photograph after just minutes of exposure (Bader & Phillips, 2002).

Vision is the least developed sense at birth. A newborn infant is extremely nearsighted, meaning she can see close objects more clearly than distant objects. The optimal viewing distance for the newborn is about 6 to 12 inches, the perfect distance for a nursing baby to focus easily on her mother’s face and make eye contact. Nevertheless, the infant’s view of the world is pretty fuzzy for the first several months, even for objects that are within close range.

The interaction between adults and infants seems to compensate naturally for the newborn’s poor vision. When adults interact with very young infants, they almost always position themselves so that their face is about 8 to 12 inches away from the baby’s face. Adults also have a strong natural tendency to exaggerate head movements and facial expressions, such as smiles and frowns, again making it easier for the baby to see them.

Physical Development

By the time infants begin crawling, at about 7 to 8 months of age, their view of the world, including distant objects, will be as clear as that of their parents. The increasing maturation of the infant’s visual system reflects the development of her brain. At birth, her brain is an impressive 25 percent of its adult weight. In contrast, her birth weight is only about 5 percent of her eventual adult weight. During infancy, her brain will grow to about 75 percent of its adult weight, while her body weight will reach only about 20 percent of her adult weight.

During the prenatal period, the top of the body develops faster than the bottom. For example, the head develops before the legs. If you’ve ever watched a 6-

A second pattern is the proximodistal trend, which refers to the tendency of infants to develop motor control from the center of their bodies outwards. Babies gain control over their abdomen before they gain control over their elbows, knees, hands, or feet.

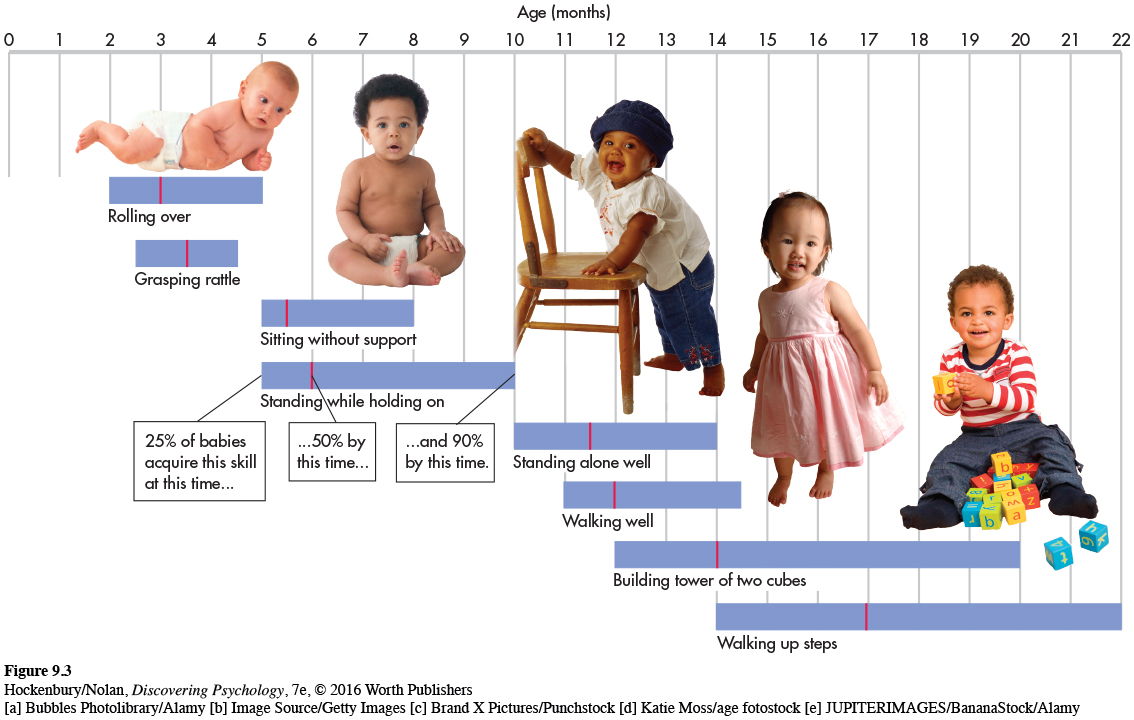

The basic sequence of motor skill development is universal, but the average ages can be a little deceptive (see Figure 9.3). As any parent knows, infants vary a great deal in the ages at which they master each skill. For example, virtually all infants are walking well by 15 months of age, but some infants will walk as early as 10 months. Each infant has her own timetable of physical maturation and developmental readiness to master different motor skills.

[d] Katie Moss/age fotostock [e] JUPITERIMAGES/BananaStock/Alamy

Social and Personality Development

From birth, forming close social and emotional relationships with caregivers is essential to the infant’s physical and psychological well-

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

Where Does the Baby Sleep?

In most U.S. families, infants sleep in their own beds (Mindell & others, 2010a). It may surprise you to discover that the United States is very unusual in this respect. In one survey of 100 societies, the United States was the only one in which babies slept in separate rooms. Another survey of 136 societies found that in two-

In one of the few in-

Mayan mothers were shocked when the American researchers told them that infants in the United States slept alone and often in a different room from their parents. They believed that the practice was cruel and unnatural, and would have negative effects on the infant’s development.

When infants and toddlers sleep alone, bedtime marks a separation from their families. To ease the child’s transition to sleeping, “putting the baby to bed” often involves lengthy bedtime rituals, including rocking, singing lullabies, or reading stories (Morrell & Steele, 2003). Small children take comforting items, such as a favorite blanket or teddy bear, to bed with them to ease the stressful transition to falling asleep alone. The child may also use his “security blanket” or “cuddly” to comfort himself when he wakes up in the night, as most small children do.

In contrast, the Mayan babies did not take cuddly items to bed, and no special routines marked the transition between wakefulness and sleep. Mayan parents were puzzled by the very idea. Instead, the Mayan babies simply went to bed when their parents did or fell asleep in the middle of the family’s social activities. Morelli and her colleagues (1992) found that the different sleeping customs of the U.S. and Mayan families reflect different cultural values. Some of the U.S. babies slept in the same room as their parents when they were first born, which the parents felt helped foster feelings of closeness and emotional security in the newborns. Nonetheless, most of the U.S. parents moved their babies to a separate room when they felt that the babies were ready to sleep alone, usually by the time they were 3 to 6 months of age. These parents explained their decision by saying that it was time for the baby to learn to be “independent” and “self-

In contrast, the Mayan parents felt that it was important to develop and encourage the infant’s feelings of interdependence with other members of the family. Thus, in both Mayan and U.S. families, sleeping arrangements reflect cultural goals for child rearing and cultural values for relations among family members.

TEMPERAMENTAL QUALITIES

BABIES ARE DIFFERENT!

Infants come into the world with very distinct and consistent behavioral styles. Some babies are consistently calm and easy to soothe. Other babies are fussy, irritable, and hard to comfort. Some babies are active and outgoing; others seem shy and wary of new experiences. Psychologists refer to these inborn predispositions to consistently behave and react in a certain way as an infant’s temperament.

Interest in infant temperament was triggered by a classic longitudinal study launched in the 1950s by psychiatrists Alexander Thomas and Stella Chess. The focus of the study was on how temperamental qualities influence adjustment throughout life. Chess and Thomas rated young infants on a variety of characteristics, such as activity level, mood, regularity in sleeping and eating, and attention span. They found that about two-

Easy babies readily adapt to new experiences, generally display positive moods and emotions, and have regular sleeping and eating patterns. Difficult babies tend to be intensely emotional, are irritable and fussy, and cry a lot. They also tend to have irregular sleeping and eating patterns. Slow-

Other temperamental patterns have been identified. For example, after decades of research, Jerome Kagan (2010a, 2010b) classified temperament in terms of reactivity. High-

Virtually all temperament researchers agree that individual differences in temperament have a genetic and biological basis (Gagne & others, 2009; Zentner & Shiner, 2012). However, researchers also agree that environmental experiences can modify a child’s basic temperament (Stack & others, 2010). As Kagan (2004) points out, “Temperament is not destiny. Many experiences will affect high and low reactive infants as they grow up. Parents who encourage a more sociable, bold persona and discourage timidity will help their high reactive children develop a less-

Because cultural attitudes affect child-

ATTACHMENT

FORMING EMOTIONAL BONDS

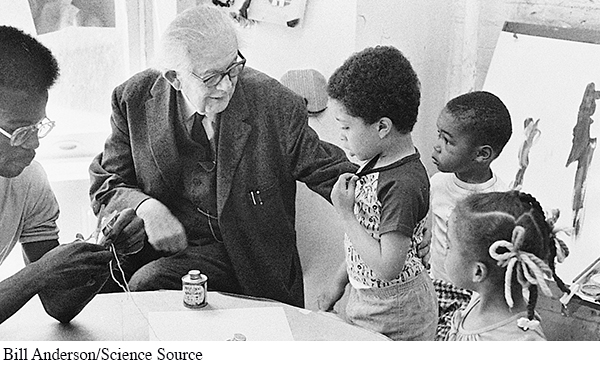

Not long after World War II, Austrian psychiatrist Rene Spitz dramatically showed the detrimental effects of institutionalization on children who were deprived of a relationship with a warm, loving caregiver. Although provided with adequate nutrition, many infants failed to thrive. Psychologist Harry Harlow (1905—

Harlow’s findings helped stimulate research on the emotional bond that forms between infants and their caregivers, especially parents, during the first year of life, which is called attachment. As conceptualized by attachment theorist John Bowlby (1969, 1988) and psychologist Mary D. Salter Ainsworth (1979), attachment relationships serve important functions throughout infancy and, indeed, the lifespan. Ideally, the parent or caregiver functions as a secure base for the infant, providing a sense of comfort and security—

Generally, when parents are consistently warm, responsive, and sensitive to their infant’s needs, the infant develops a secure attachment to her parents (Belsky, 2006). The infant’s expectation that her needs will be met by her caregivers is the most essential ingredient in forming a secure attachment to them. And, studies have confirmed that sensitivity to the infant’s needs is associated with secure attachment across diverse cultures (van IJzendoorn & Sagi-

In contrast, insecure attachment may develop when an infant’s parents are neglectful, inconsistent, or insensitive to his moods or behaviors. Insecure attachment seems to reflect an ambivalent or detached emotional relationship between an infant and his parents (Ainsworth, 1979; Isabella & others, 1989).

How do researchers measure attachment? The most commonly used procedure, called the Strange Situation, was devised by Ainsworth. The Strange Situation is typically used with infants who are between 1 and 2 years old (Ainsworth & others, 1978). In this technique, the baby and his mother are brought into an unfamiliar room with a variety of toys. A few minutes later, a stranger enters the room. The mother stays with the baby for a few moments, then departs, leaving the baby alone with the stranger. After a few minutes, the mother returns, spends a few minutes in the room, leaves, and returns again. Through a one-

Psychologists assess attachment by observing the child’s behavior toward his mother during the Strange Situation procedure. When his mother is present, the securely attached baby will use her as a “secure base” from which to explore the new environment, periodically returning to her side. He will show distress when his mother leaves the room and will greet her warmly when she returns. A securely attached baby is easily soothed by his mother (Ainsworth & others, 1978; Lamb & others, 1985).

In contrast, an insecurely attached infant is less likely to explore the environment, even when her mother is present. In the Strange Situation, insecurely attached infants may appear either very anxious or completely indifferent. Such infants tend to ignore or avoid their mothers when they are present. Some insecurely attached infants become extremely distressed when their mothers leave the room. When insecurely attached infants are reunited with their mothers, they are hard to soothe and may resist their mothers’ attempts to comfort them.

In studying attachment, psychologists have typically focused on the infant’s bond with the mother, since the mother is often the infant’s primary caregiver. Still, it’s important to note that most fathers are also directly involved with the basic care of their infants and children. As is the case with mothers, children are more likely to be securely attached to fathers who are involved with their care and sensitive to their needs (Brown & others, 2012). In homes where both parents are present, children who are attached to one parent are usually also attached to the other (Furman & Simon, 2004). Finally, infants are capable of forming attachments to other consistent caregivers in their lives, such as relatives or workers at a day-

The quality of attachment during infancy is associated with a variety of long-

Because attachment in infancy seems to be so important, psychologists have extensively investigated the impact of day care on attachment. Later in the chapter, we’ll take a close look at this issue (see p. 401).

Language Development

Probably no other accomplishment in early life is as astounding as language development. By the time a child reaches 3 years of age, he will have learned thousands of words and the complex rules of his language.

According to linguist Noam Chomsky (1965), every child is born with a biological predisposition to learn language —any language. In effect, children possess a “universal grammar”—a basic understanding of the common principles of language organization. Infants are innately equipped not only to understand language but also to extract grammatical rules from what they hear. The key task in the development of language is to learn a set of grammatical rules that allows the child to produce an unlimited number of sentences from a limited number of words.

At birth, infants can distinguish among the speech sounds of all the world’s languages, no matter what language is spoken in their homes (Kuhl, 2004; Werker & Desjardins, 1995). And shortly after birth, infants prefer speech over other sounds that humans make (Shultz & others, 2014). But infants lose the ability to distinguish among all possible speech sounds by 10 to 12 months of age. Instead, they can distinguish only among the speech sounds that are present in the language to which they have been exposed (Kuhl & others, 1992; Yoshida & others, 2010). Thus, during the first year of life, infants begin to master the sound structure of their own native language.

ENCOURAGING LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

Just as infants seem to be biologically programmed to learn language, parents are predisposed to encourage language development by the way they speak to infants and toddlers. People in every culture, especially parents, use a style of speech called motherese, parentese, or infant-

Infant-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that talking “baby talk” to infants and toddlers won’t harm their language development?

The adult use of infant-

And, infants seem to prefer infant-

THE COOING AND BABBLING STAGE OF LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

As with many other aspects of development, the stages of language development appear to be universal (Kuhl, 2004). In virtually every culture, infants follow the same sequence of language development and at roughly similar ages.

At about 3 months of age, infants begin to “coo,” repeating vowel sounds such as ahhhhh or ooooo, varying the pitch up or down. At about 5 months of age, infants begin to babble. They add consonants to the vowels and string the sounds together in sometimes long-

When infants babble, they are not simply imitating adult speech. Infants all over the world use the same sounds when they babble, including sounds that do not occur in the language of their parents and other caregivers. At around 9 months of age, babies begin to babble more in the sounds specific to their language. Babbling, then, seems to be a biologically programmed stage of language development (Gentilucci & Dalla Volta, 2007; Petitto & others, 2004).

THE ONE-

Long before babies become accomplished talkers, they understand much of what is said to them. Before they are a year old, most infants can understand simple commands, such as “Bring Daddy the block,” even though they cannot say the words bring, Daddy, or block. This reflects the fact that an infant’s comprehension vocabulary (the words she understands) is much larger than her production vocabulary (the words she can say). Generally, infants acquire comprehension of words more than twice as fast as they learn to speak new words.

Somewhere around their first birthday, infants produce their first real words. First words usually refer to concrete objects or people that are important to the child, such as mama, daddy, or ba-

SCIENCE VERSUS PSEUDOSCIENCE

Can a DVD Program Your Baby to Be a Genius?

It’s a marketing phenomenon: Videos developed specifically for infants and very young toddlers, with catchy titles like Smart Baby, Brainy Baby, and Baby Einstein. When the first Baby Einstein video was released in 1997, ads claimed that it promoted infant brain development (Bronson & Merryman, 2009).

Although the makers of Baby Einstein no longer feature such explicit claims in their advertising, most companies that market baby media either imply or state outright that their products are educational and will help infants learn (Wartella & others, 2010). No doubt fueled by the hope that viewing such media would benefit their babies, parents spend hundreds of millions of dollars annually on baby video products in the United States alone (DeLoache & others, 2010; Rideout, 2007).

But how effective are such videos? Do infants learn from watching them? Let’s look at the evidence.

The first surprise came from a large study that showed that viewing baby media was actually negatively correlated with vocabulary growth in infants. Developmental psychologist Frederick J. Zimmerman and his colleagues (2007) found that babies who never watched “educational” videos knew more words than babies who did. In fact, the more time infants spent watching baby media, the fewer words they knew.

Interestingly, the deficit in language skills was associated only with watching media designed for infant learning—

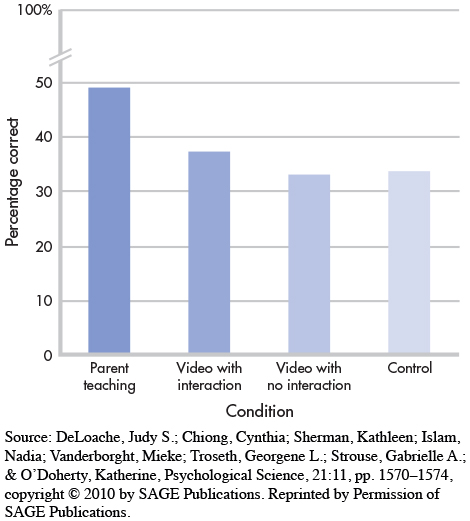

One potential drawback of this study was that it was correlational and relied heavily on parent surveys. So, developmental psychologist Judy DeLoache and her colleagues (2010) designed a rigorously controlled experiment in which the infants would be objectively tested for their knowledge of the specific words that were taught on a popular video.

Twelve-

In the video-

with- condition, the children watched the DVD alone at least five times a week over a 4-no- interaction week period. In the video-

with- condition, the children watched the DVD with a parent for the same amount of time.interaction In the parent-

teaching condition, the children had no exposure to the video at all. Instead, the parents were given a list of the 25 common words featured on the video and were instructed to “try to teach your child as many of these words as you can in whatever way seems natural to you.”Finally, in the control condition, the children were not exposed to the video and the parents were not instructed to try to teach them the words. Instead, they were simply tested for their word knowledge before and after the 4-

week period.

Why was including a control condition so important? Put simply, because children naturally learn a lot of words during this period of development. Thus, the control condition provided a benchmark of normal vocabulary growth against which the experimental groups could be compared.

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that educational videos, like Baby Einstein, help babies learn how to talk?

What were the results? As shown in the graph, babies learned the most words from interacting with their parents. In contrast, despite extensive exposure to a video designed to teach them specific words, infants in the video groups did not learn any more new words than did children with no exposure to the video at all.

Was it because the infants found the videos boring, or didn’t pay attention to them? No. Parents reported that their babies were mesmerized by the program. However, in an interesting twist, DeLoache and her colleagues (2010) found that there was no correlation between how much the parents thought their child learned from the video and how much their child had actually learned. However, the more parents liked the video, the more they thought their child had learned from it.

This finding may help explain the many enthusiastic testimonials in marketing materials for baby media. Even though there was no difference in how many words were learned, parents who had a favorable attitude toward the video thought that their children had learned more because of viewing it. One possible explanation is illusory correlation: Parents may misattribute normal developmental progress to the child’s exposure to the video.

Since the research on baby media began to be published, some companies, like the producers of Baby Einstein, have revised their marketing materials to emphasize the “engaging” nature of the media rather than its “educational” nature. The research is clear: Interacting with a parent or other caregiver is by far the most effective way to increase an infant’s cognitive and, especially, language skills.

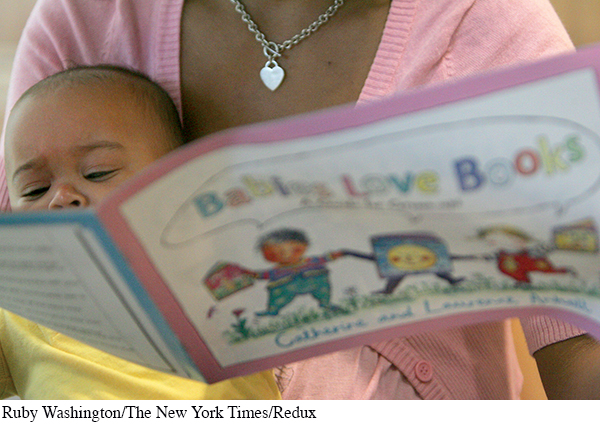

The bottom line: Save your money and talk to your baby. Better yet, read to him! Several studies have found that the best predictor of infant language is the amount of time that parents spend reading to their children (Robb & others, 2009).

During the one-

Many new parents, eager to accelerate their young children’s language and cognitive development, purchase DVDs or videos that claim to educate as well as entertain the growing child. But what do babies learn from baby videos? We take a critical look at this question in the Science Versus Pseudoscience box, “Can a DVD Program Your Baby to Be a Genius?”

THE TWO-

Around their second birthday, toddlers begin putting words together. During the two-

At around 2½ years of age, children move beyond the two-

Gender Development

BLUE BEARS AND PINK BUNNIES

KEY THEME

Gender refers to the social and cultural aspects associated with being male or female.

KEY QUESTIONS

What gender differences develop during childhood?

What are the major theories that explain gender development?

Because the English language is less than precise, we need to clarify a few terms before we begin our discussion of gender development. First, we’ll use the term gender to refer to the cultural and social meanings that are associated with maleness and femaleness. Thus, gender role describes the behaviors, attitudes, and personality traits that a given culture designates as either “masculine” or “feminine” (Wood & Eagly, 2009). Finally, gender identity refers to a person’s psychological sense of being male or female (Egan & Perry, 2001). When the biological categories of “male” and “female” are being discussed, we’ll use the term sex.

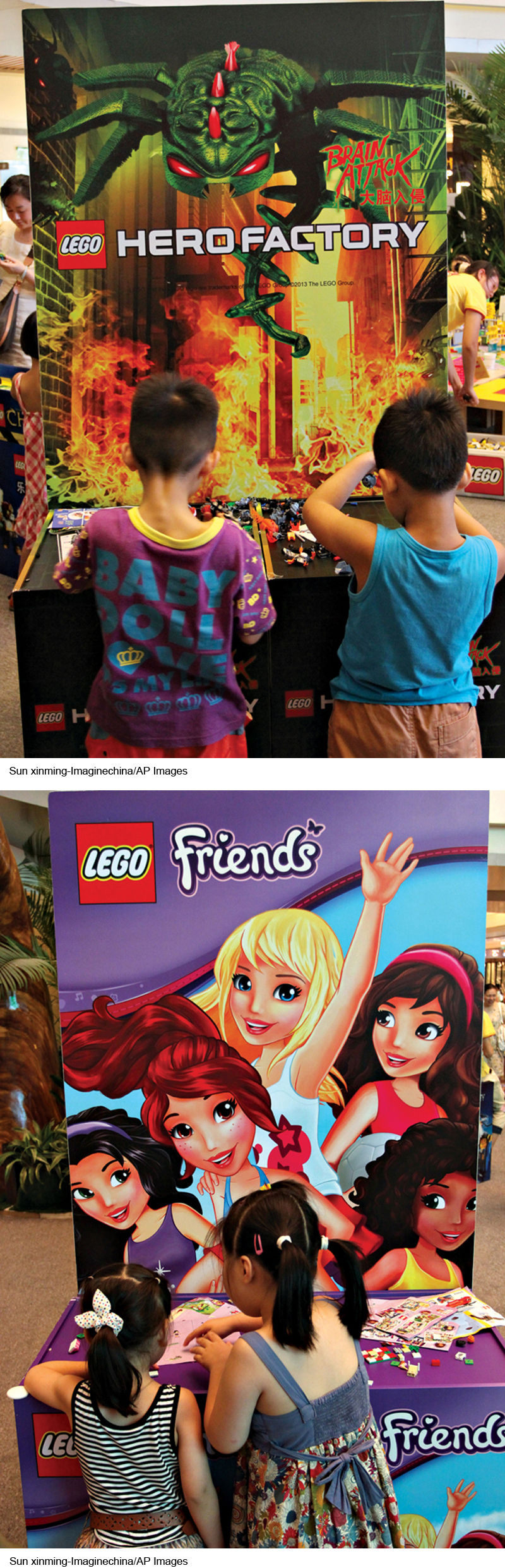

Being male or female does make a vast difference in most societies. In the United States, newborn babies are often “color-

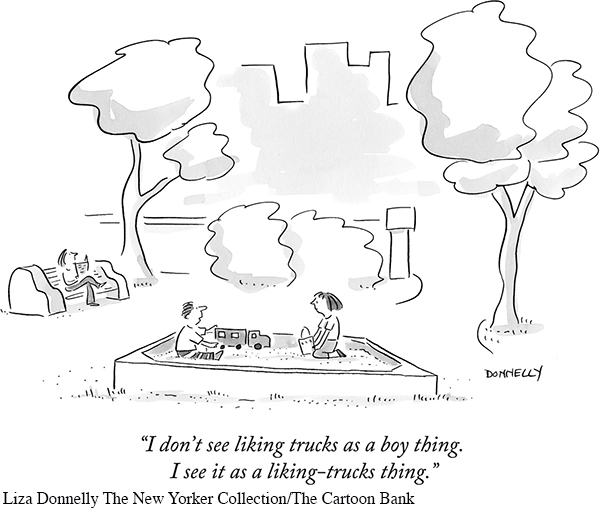

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN CHILDHOOD BEHAVIOR SPIDER-

Most toddlers begin using gender labels between the ages of 18 and 21 months. And, roughly between the ages of 2 and 3, children can identify themselves and other children as boys or girls, although the details are still a bit fuzzy to them (Zosuls & others, 2009). Preschoolers don’t yet understand that sex is determined by physical characteristics. This is not surprising, considering that the biologically defining sex characteristics—

From about the age of 18 months to the age of 2 years, sex differences in behavior begin to emerge (Miller & others, 2006). These differences become more pronounced throughout early childhood. Toddler girls play more with soft toys and dolls, and ask for help from adults more than toddler boys do. Toddler boys play more with blocks and transportation toys, such as trucks and wagons. They also play more actively than do girls (see Ruble & others, 2006).

Roughly between the ages of 2 and 3, preschoolers start acquiring gender-

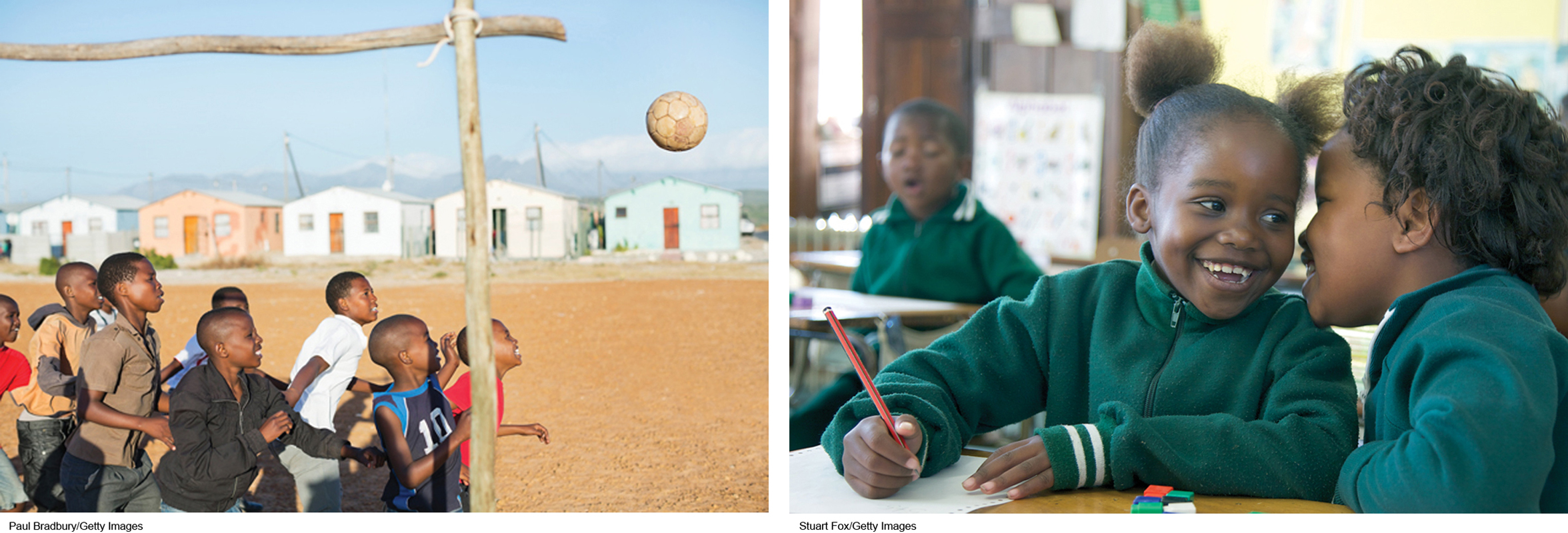

Children also develop a strong preference for playing with members of their own sex—

According to psychologist Carole Beal (1994), boys and girls seem to almost create separate “social worlds,” each with its own style of interaction. They also learn particular ways of interacting that work well with peers of the same sex. For example, boys learn to assert themselves within a group of male friends. Girls tend to establish very close bonds with one or two friends. Girls learn to maintain their close friendships through compromise, conciliation, and verbal conflict resolution.

Children are far more rigid than adults in their beliefs in gender-

What causes this girl to choose a particular toy? Watch Video Activity: Gender Development.

Girls’ more flexible attitude toward gender roles may reflect society’s greater tolerance of girls who cross gender lines in attire and behavior. A girl who plays with boys, or who plays with boys’ toys, may develop the grudging respect of both sexes. But a boy who plays with girls or with girls’ toys may be ostracized by both sexes. Girls are often proud to be labeled a “tomboy,” but for many boys, being called a “sissy” is still the ultimate insult (Thorne, 1993). This helps to explain why James’s parents were fine with him calling himself a tomboy, a socially acceptable term for girls.

James has observed others’ expectations from the vantage point of having lived as both female and male at different points in his life. As a guy, James frequently fields questions about why he is not into stereotypically masculine activities, such as weight lifting. James explains that he hates stereotypes, noting, “I’m not the geek/nerd stereotype. But, if you are going to stick me in a category, I’m that one. I’m not a jock.” And he hates expectations about how he should dress: “Like you are not allowed to wear bright colors anymore because you’re a man?”

EXPLAINING GENDER DIFFERENCES

CONTEMPORARY THEORIES

Many theories have been proposed to explain the differing patterns of male and female behavior in our culture and in other cultures (see Reid & others, 2008). Gender theories have included findings and opinions from anthropology, sociology, neuroscience, medicine, philosophy, political science, economics, and religion. (Let’s face it, you probably have a few opinions on the issue yourself.) We won’t even attempt to cover the full range of ideas. Instead, we’ll describe three categories of influential psychological theories.

Historically, Alice Eagly and Wendy Wood (2013) observed, most psychologists have explained gender differences with a focus mostly on sociocultural explanations or mostly on biological explanations. Eagly and Wood argue that both viewpoints are important. Based on Eagly and Wood’s premise, we will discuss some explanations based primarily on sociocultural factors including social learning theory and gender schema theory, some explanations based primarily on biological factors including evolutionary theory, and interactionist theories that combine both approaches. In Chapter 10 on personality we will discuss Freud’s ideas on the development of gender roles.

Children are gender detectives who search for cues about gender—

—Carol Lynn Martin and Diane Ruble (2004)

Social Learning Theory: Learning Gender Roles Based on the principles of learning, the social learning theory of gender-

How do children acquire their understanding of gender norms? Children are exposed to many sources of information about gender roles, including television, video games, books, films, and observation of same-

Gender Schema Theory: Constructing Gender Categories Gender schema theory, developed by Sandra Bem, incorporates some aspects of social learning theory (Renk & others, 2006; Martin & others, 2004). However, Bem (1981) approached gender-

Like schemas in general (see Chapter 6), children’s gender schemas do seem to influence what they notice and remember. For example, in a classic experiment, 5-

Children also readily assimilate new information into their existing gender schemas (Miller & others, 2006). In another classic study, 4-

Gender schemas can be subtle. For example, a carefully designed study of almost 60 different children’s coloring books found that gender stereotypes were widespread. Males were more likely to be depicted as animals, adults, and superheroes. Females, on the other hand, were more likely to be depicted as children and humans (Fitzpatrick & McPherson, 2010).

Given the gender-

Evolutionary Theories Some researchers use primarily biological explanations to explain gender differences in behavior and personality. Perhaps the most prominent of the biological explanations are those that cite evolution as the primary cause of many gender differences. According to the evolutionary approach, gender differences are the result of generations of the dual forces of sexual selection and parental investment (Hyde, 2014). Physical and psychological characteristics—

Evolutionary explanations have been explored for gender differences in a number of areas, including the expression of anger (see Archer, 2004). Specifically, gender differences in the expression of aggressive tendencies have been observed even in very young children, a suggestion that they may be genetic. Why might this occur? In many species of mammals, including humans, aggression has served a useful evolutionary purpose, increasing the odds that a male will best his fellow males in competition to mate with the females of the species.

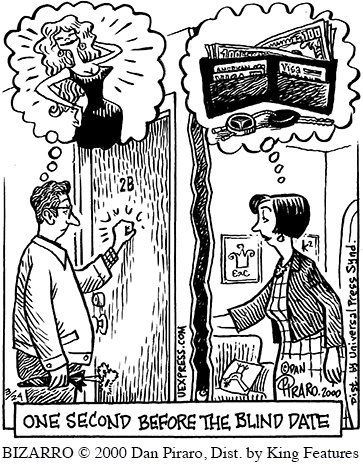

We also see evolutionary explanations for behaviors in adulthood, including for mate preferences (Schmitt & others, 2012). To investigate mate preferences, psychologist David Buss (1994, 2009) coordinated a large-

Buss, an evolutionary psychologist, interprets these gender differences as reflecting the different “mating strategies” of men and women (1995a, 2009, 2011). He contends that men and women face very different “adaptive problems” in selecting a mate. According to Buss (1995b, 1996), the adaptive problem for men is to identify and mate with women who are likely to be successful at bearing their children. Thus, men are more likely to place a high value on youth, because it is associated with fertility, and physical attractiveness, because it signals that the woman is probably physically healthy and has high-

The evolutionary explanation of sex differences, whether in mate preferences or other areas, is controversial (Confer & others, 2010). Some psychologists argue that it is overly deterministic and does not sufficiently acknowledge the role of culture, gender-

With respect to his research on mate preferences, Buss (2011) reported that his extensive survey also found that men and women in all 37 cultures agreed that the most important factor in choosing a mate was mutual attraction and love. And both sexes rated kindness, intelligence, emotional stability, health, and a pleasing personality as more important than a prospective mate’s financial resources or good looks.

Buss also flatly states that explaining some of the reasons that might underlie sexual inequality does not mean that sexual inequality is natural, correct, or justified. Rather, evolutionary psychologists believe that we must understand the conditions that foster sexual inequality in order to overcome or change those conditions (Buss & Schmitt, 2011).

Interactionist Theories Eagly and Wood (2013) point out that there are many areas of agreement between those who favor sociocultural explanations and those who favor biological explanations. They encourage the development of interactionist theories that explain a given observation using a combination of explanations.

Let’s look at one example highlighted by Eagly and Wood (2013)—the division of labor along gender lines. Eagly and Wood observe that men tend to be physically larger and stronger than women and that women are biologically responsible for reproduction. These biological differences mean that it can be more efficient for men and boys to be responsible for some activities—

For example, since James began living as a man, several people have wondered why he does not engage in masculine athletic feats. “You should lift weights,” he’s been told as a man, but not as a woman. This suggestion draws on gender role beliefs about what women and men should do, rather than examining James’s biological abilities—

Biology plays a role in what women and men do, but both women and men might be prevented from taking part in certain activities for reasons other than biological or physical limitations. Psychological and socially driven beliefs about talents and abilities can also limit opportunities and choices. From the interactionist perspective, it is the interplay of biological constraints and psychological and social constraints that drives the division of labor.

Eagly and Wood (2013) admit that it is challenging to incorporate the many biological and sociocultural influences that might drive any given behavior. However, they see attempts at integrating explanations from the two categories as essential to gaining a fuller understanding of the psychology of sex and gender.

GENDER IDENTITY

As we have seen in this section of the chapter, boys and girls and men and women are different, but they are not polar opposites. Instead, there is a great deal of overlap between them. Rather than being black and white, personality and biological differences more often reflect shades of gray. But whether those shades of gray tend to be light or dark, most people develop a clear sense of gender identity as either male or female. And, for most people, their sense of gender identity is consistent with their physical anatomy. But for a significant minority of people, including James, gender identity and physical anatomy are not consistent. In an increasingly visible variation on gender identity, transgender individuals are anatomically “normal”—they are biologically male or female. However, their gender identity is in conflict with their biological sex (Sohn & Bosinski, 2007). A transgender man, such as James, is an anatomical female who identifies with or wishes to become male. A transgender woman is an anatomical male who identifies with or wishes to become female. And, a cisgender man or woman refers to a person whose anatomy matches their gender identity, such as a biological woman who identifies as a woman. Because this situation is viewed as the norm, the term is infrequently used.

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that transgender people are homosexual?

Like James, the typical transgender person has the strong feeling, often present since childhood, of having been born in the body of the wrong sex (Cohen-

Transgender individuals, including James, continue to face discrimination and prejudice many aspects of their lives. Elsa, a young transgender girl living in Colorado, hated when people called her a boy. When she tried to correct them, she was teased. She told her parents, “I wish I didn’t exist” (Brown, 2015). But some would argue that the lives of transgender people are not all that different from those of people with a more conventional gender identity. Remember that James, like others at his stage of development, wants a house and a family. He is an emerging adult, a stage we will discuss later in this chapter, and is actively trying to find his place in the world. Being transgender is just one part of his development.

Cognitive Development

KEY THEME

According to Piaget’s theory, children progress through four distinct cognitive stages, and each stage marks a shift in how they think and understand the world.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are Piaget’s four stages of cognitive development?

What are three criticisms of Piaget’s theory?

How do Vygotsky’s ideas about cognitive development differ from Piaget’s theory?

Just as children advance in motor skill and language development, they also develop increasing sophistication in cognitive processes—

Piaget (1952, 1972) believed that children actively try to make sense of their environment rather than passively soaking up information about the world. To Piaget, many of the “cute” things children say actually reflect their sincere attempts to make sense of their world. In fact, Piaget carefully observed his own three children in developing his theory and published three books about them (Boeree, 2006).

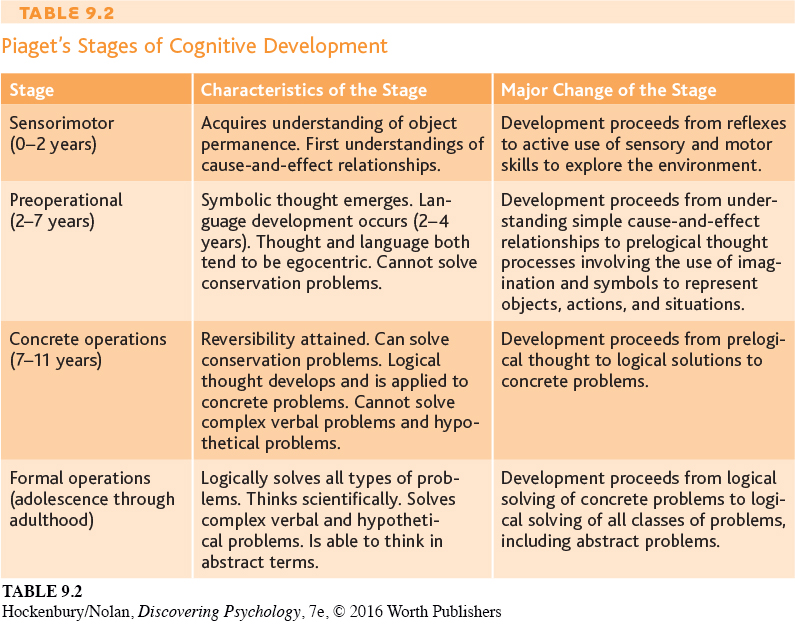

According to Piaget, children progress through four distinct cognitive stages: the sensorimotor stage, from birth to age 2; the preoperational stage, from age 2 to age 7; the concrete operational stage, from age 7 to age 11; and the formal operational stage, which begins during adolescence and continues into adulthood. As a child advances to a new stage, his thinking is qualitatively different from that of the previous stage. In other words, each new stage represents a fundamental shift in how the child thinks and understands the world.

Piaget saw this progression of cognitive development as a continuous, gradual process. As a child develops and matures, she does not simply acquire more information. Rather, she develops a new understanding of the world in each progressive stage, building on the understandings acquired in the previous stage (Piaget, 1961). As the child assimilates new information and experiences, she eventually changes her way of thinking to accommodate new knowledge (Piaget, 1961).

Piaget (1971) believed that these stages were biologically programmed to unfold at their respective ages. He also believed that children in every culture progressed through the same sequence of stages at roughly similar ages. However, Piaget also recognized that hereditary and environmental differences could influence the rate at which a given child progressed through the stages.

For example, a “bright” child may progress through the stages faster than a child who is less intellectually capable. A child whose environment provides ample and varied opportunities for exploration is likely to progress faster than a child who has limited environmental opportunities. Thus, even though the sequence of stages is universal, there can be individual variation in the rate of cognitive development.

THE SENSORIMOTOR STAGE

The sensorimotor stage extends from birth until about 2 years of age. During this stage, infants acquire knowledge about the world through actions that allow them to directly experience and manipulate objects. Infants discover a wealth of very practical sensory knowledge, such as what objects look like and how they taste, feel, smell, and sound.

Infants in this stage also expand their practical knowledge about motor actions—

At the beginning of the sensorimotor stage, the infant’s motto seems to be “Out of sight, out of mind.” An object exists only if she can directly sense it. For example, if a 4-

However, by the end of the sensorimotor stage, children acquire a new cognitive understanding, called object permanence. Object permanence is the understanding that an object continues to exist even if it can’t be seen. Now the infant will actively search for a ball that she has watched roll out of sight (Mash & others, 2006). Infants gradually acquire an understanding of object permanence as they gain experience with objects, as their memory abilities improve, and as they develop mental representations of the world, which Piaget called schemas (Perry & others, 2008).

THE PREOPERATIONAL STAGE

The preoperational stage lasts from roughly age 2 to age 7. In Piaget’s theory, the word operations refers to logical mental activities. Thus, the “preoperational” stage is a prelogical stage.

The hallmark of preoperational thought is the child’s capacity to engage in symbolic thought. Symbolic thought refers to the ability to use words, images, and symbols to represent the world. One indication of the expanding capacity for symbolic thought is the child’s impressive gains in language during this stage.

The child’s increasing capacity for symbolic thought is also apparent in her use of fantasy and imagination while playing. A discarded box becomes a spaceship, a house, or a fort as children imaginatively take on the roles of different characters. Some children even create an imaginary companion (Taylor & others, 2009). One study of children’s role playing documented both imaginary friends like “Pajama Sam,” who has “rainbow hair, blue and yellow eyes, [and] sometimes has a bird on his head” and objects that come to life, such as “Marshmallow,” who is “a stuffed dog with orange hair who is afraid of the dark, [and] likes to ride in cars, and go camping” (Taylor & others, 2013).

Still, the preoperational child’s understanding of symbols remains immature. A 2-

The thinking of preoperational children often displays egocentrism. By egocentrism, Piaget did not mean selfishness or conceit. Rather, egocentric children lack the ability to consider events from another person’s point of view. Thus, the young child genuinely thinks that Grandma would like a new Lego set or a video game for her upcoming birthday because that’s what he wants. Egocentric thought is also operating when the child silently nods his head in answer to Grandpa’s question on the telephone.

The preoperational child’s thought is also characterized by irreversibility and centration. Irreversibility means that the child cannot mentally reverse a sequence of events or logical operations back to the starting point. For example, the child doesn’t understand that adding “3 plus 1” and adding “1 plus 3” refer to the same logical operation. Centration refers to the tendency to focus, or center, on only one aspect of a situation, usually a perceptual aspect. In doing so, the child ignores other relevant aspects of the situation.

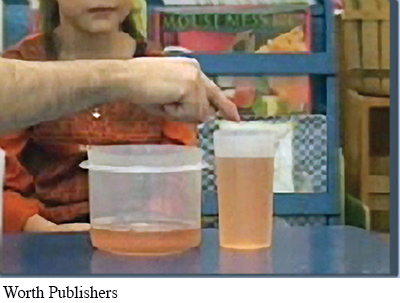

The classic demonstration of both irreversibility and centration involves a task devised by Piaget. When Sandy and Don’s daughter Laura was 5, they tried this task with her. First, they showed her two identical glasses, each containing exactly the same amount of liquid. Laura easily recognized the two amounts of liquid as being the same.

When Laura was almost 3, your author Sandy and her daughter Laura were investigating the tadpoles in the creek behind their home. “Do you know what tadpoles become when they grow up? They become frogs,” Sandy explained. Laura looked very serious. After considering this new bit of information for a few moments, she asked, “Laura grow up to be a frog, too?”

Then, while Laura watched intently, Sandy poured the liquid from one of the glasses into a third container that was much taller and narrower than the others. “Which container,” Sandy asked, “holds more liquid?” Like any other preoperational child, Laura answered confidently, “The taller one!” Even when the procedure was repeated, reversing the steps over and over again, Laura remained convinced that the taller container held more liquid than did the shorter container.

This classic demonstration illustrates the preoperational child’s inability to understand conservation. The principle of conservation holds that two equal physical quantities remain equal even if the appearance of one is changed, as long as nothing is added or subtracted (Piaget & Inhelder, 1974). Because of centration, the child cannot simultaneously consider the height and the width of the liquid in the container. Instead, the child focuses on only one aspect of the situation, the height of the liquid. And because of irreversibility, the child cannot cognitively reverse the series of events, mentally returning the poured liquid to its original container. Thus, she fails to understand that the two amounts of liquid are still the same.

THE CONCRETE OPERATIONAL STAGE

With the beginning of the concrete operational stage, at around age 7, children become capable of true logical thought. They are much less egocentric in their thinking, can reverse mental operations, and can focus simultaneously on two aspects of a problem. In short, they understand the principle of conservation. When presented with two rows of pennies, each row equally spaced, concrete operational children understand that the number of pennies in each row remains the same even when the spacing between the pennies in one row is increased.

Think Like a SCIENTIST

Children’s cognition is also affected by environmental factors. For example, what classroom decor better helps kindergarten students learn? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Learning Environments

As the name of this stage implies, thinking and use of logic tend to be limited to concrete reality—

THE FORMAL OPERATIONAL STAGE

At the beginning of adolescence, children enter the formal operational stage. In terms of problem solving, the formal operational adolescent is much more systematic and logical than the concrete operational child (Kuhn & Franklin, 2006). Formal operational thought reflects the ability to think logically even when dealing with abstract concepts or hypothetical situations (Kuhn, 2008; Piaget, 1972; Piaget & Inhelder, 1958). In contrast to the concrete operational child, the formal operational adolescent explains friendship by emphasizing more global and abstract characteristics, such as mutual trust, empathy, loyalty, consistency, and shared beliefs (Harter, 1990).

But, like the development of cognitive abilities during infancy and childhood, formal operational thought emerges only gradually. Formal operational thought continues to increase in sophistication throughout adolescence and adulthood. Although an adolescent may deal effectively with abstract ideas in one domain of knowledge, his thinking may not reflect the same degree of sophistication in other areas. Piaget (1973) acknowledged that even among many adults, formal operational thinking is often limited to areas in which they have developed expertise or a special interest. Table 9.2 below summarizes Piaget’s stages of cognitive development.

CRITICISMS OF PIAGET’S THEORY

Piaget’s theory has inspired hundreds, if not thousands, of research studies, and he is considered one of the most important scientists of the twentieth century (Perret-

Try Concept Practice: Piaget and Conservation for video demonstrations of Piaget’s conservation principles.

Criticism 1: Piaget underestimated the cognitive abilities of infants and young children. To test for object permanence, Piaget would show an infant an object, cover it with a cloth, and then observe whether the infant tried to reach under the cloth for the object. Using this procedure, Piaget found that it wasn’t until an infant was about 9 months old that she behaved as if the object continued to exist after it was hidden.

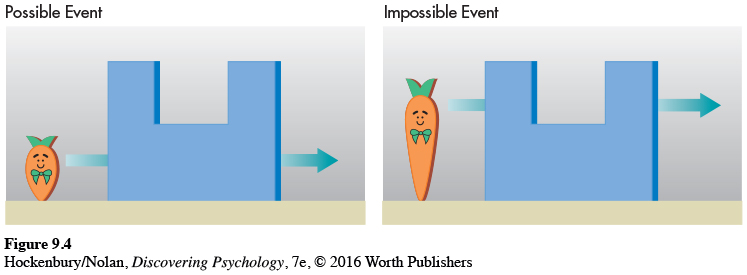

But what if the infant “knew” that the object was under the cloth but simply lacked the physical coordination to reach for it? How could you test this hypothesis? Rather than using manual tasks to assess object permanence and other cognitive abilities, Renée Baillargeon developed a method based on visual tasks. Baillargeon’s research is based on the premise that infants, like adults, will look longer at “surprising” events that appear to contradict their understanding of the world (Baillargeon & others, 2011, 2012).

In this research paradigm, the infant first watches an expected event, which is consistent with the understanding that is being tested. Then, the infant is shown an unexpected event. If the unexpected event violates the infant’s understanding of physical principles, he should be surprised and look longer at the unexpected event than the expected event.

Figure 9.4 shows one of Baillargeon’s classic tests of object permanence, conducted with Julie DeVos (Baillargeon & DeVos, 1991). If the infant understands that objects continue to exist even when they are hidden, she will be surprised when the tall carrot unexpectedly does not appear in the window of the panel.

Using variations of this basic experimental procedure, Baillargeon and her colleagues have shown that infants as young as 2½ months of age display object permanence (Baillargeon & others, 2009; Luo & others, 2009). This is more than six months earlier than the age at which Piaget believed infants first showed evidence of object permanence.

Piaget’s discoveries laid the groundwork for our understanding of cognitive development. However, as developmental psychologists Jeanne Shinskey and Yuko Munakata (2005) observe, today’s researchers recognize that “what infants appear to know depends heavily on how they are tested.”

Criticism 2: Piaget underestimated the impact of the social and cultural environment on cognitive development. In contrast to Piaget, the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky believed that cognitive development is strongly influenced by social and cultural factors. Vygotsky formulated his theory of cognitive development at about the same time Piaget formulated his. However, Vygotsky’s writings did not become available in the West until many years after his untimely death from tuberculosis in 1934 (Rowe & Wertsch, 2002; van Geert, 1998).

Vygotsky agreed with Piaget that children may be able to reach a particular cognitive level through their own efforts. However, Vygotsky (1978, 1987) argued that children are able to attain higher levels of cognitive development through the support and instruction that they receive from other people. Researchers have confirmed that social interactions, especially with older children and adults, play a significant role in a child’s cognitive development (Psaltis & others, 2009; Wertsch, 2008). Interventions aimed at increasing social interactions seem to be particularly important for children in lower-

One of Vygotsky’s important ideas was his notion of the zone of proximal development. This refers to the gap between what children can accomplish on their own and what they can accomplish with the help of others who are more competent (Holzman, 2009). Note that the word proximal means “nearby,” indicating that the assistance provided goes just slightly beyond the child’s current abilities. Such guidance can help “stretch” the child’s cognitive abilities to new levels.

Cross-

Criticism 3: Piaget overestimated the degree to which people achieve formal operational thought processes. Researchers have found that many adults display abstract-

Rather than distinct stages of cognitive development, some developmental psychologists emphasize the information-

With the exceptions that have been noted, Piaget’s observations of the changes in children’s cognitive abilities are fundamentally accurate. His description of the distinct cognitive changes that occur during infancy and childhood ranks as one of the most outstanding contributions to developmental psychology.

Test your understanding of Infancy and Childhood with  .

.