Late Adulthood and Aging

KEY THEME

Late adulthood does not necessarily involve a steep decline in physical or cognitive capabilities.

KEY QUESTIONS

What cognitive changes take place in late adulthood?

What factors influence social development in late adulthood?

The average life expectancy for men in the United States is currently about 76 years, and for women, about 81 years (Xu & others, 2009). Thus, the stage of late adulthood can easily last a decade or more. It has been projected that by 2050, the number of United States residents over the age of 65 will double, going from 40 million today to 89 million (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). The world population is aging, too. Globally, the number of people aged 80 and older is expected to grow from 69 million in 2014 to 379 million in 2050 (Harper, 2014).

Although we experience many physical and sensory changes throughout adulthood, that’s not to say that we completely fall apart when we reach our 60s, 70s, or even 80s. Contrary to many young people’s misconceptions of late adulthood, most older adults live healthy, active, and self-

Cognitive Changes

During which decade of life do you think people reach their intellectual peak? If you answered the 20s or 30s, you may be surprised by the results of research. There is a lot of variability in terms of the age at which different cognitive abilities are at their peak (Hartshorne & Germine, 2015). One study of business executives found that older executives performed more poorly than younger executives on some measures of cognitive ability but performed better on others (Klein & others, 2015).

Decades of work by K. Warner Schaie (1995, 2005) and his colleagues has shown that mental abilities remain relatively stable until about the age of 60. And in terms of mental abilities related to what we do—

But even after age 60, most older adults maintain their previous levels of ability. A longitudinal study of adults in their 70s, 80s, and 90s found that there were slight but significant declines in memory, perceptual speed, and fluency. However, measures of knowledge, such as vocabulary, remained stable up to age 90 (Singer & others, 2003; Zelinski & Kennison, 2007). Similarly, the ability to speak and understand language tends to remain stable as people age (Shafto & Tyler, 2014). When declines in mental abilities occur during old age, Schaie (2005) found that the explanation is often simply a lack of practice or experience with the kinds of tasks used in mental ability tests. Even just a few hours of training on mental skills can improve test scores for most older adults.

Some research suggests that physiological functioning of the brain begins to slow with age (Salthouse, 2009). Neurons appear to become less efficient at communicating with one another, and this seems to result in slowed and sometimes inhibited cognitive performance (Bucur & others, 2008). According to one hypothesis, older brains appear to compensate for this decline in processing speed by outsourcing some of the work to other parts of the brain (Dennis & Cabeza, 2008). However, the need to recruit more regions of the brain comes at a price—

Is it possible to minimize declines in mental and physical abilities in old age? In a word, yes. Consistently, research has found that those who are better educated and engage in physical, mental, and social activities throughout older adulthood show the smallest declines in mental abilities (Boron & others, 2007; Colcombe & Kramer, 2003; Lindenberger, 2014). However, dysfunctional social relationships can have negative effects. In one study of more than 10,000 people living in the United Kingdom, close relationships that caused worry and stress predicted a decline in mental abilities eight years later (Liao & others, 2014). Aerobic exercise, however, has strong research support for its effectiveness in improving cognitive functioning in late adulthood (Hertzog & others, 2009). The Focus on Neuroscience “Boosting the Aging Brain” provides a look at a new experiment that demonstrated the remarkable effects of a moderate exercise program on the brains of elderly adults.

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

Boosting the Aging Brain

Dozens of studies have shown that exercise, especially aerobic exercise, improves cognitive functioning in old age (Colcombe & Kramer, 2003; Hillman & others, 2008). Many studies have also shown that remaining mentally and physically active decreases age-

However, most human studies on brain structure have been correlational, rather than experimental, making it difficult to pin down causation. Does staying physically active improve cognitive functioning and brain health in old age? Or are people with better cognitive functioning and brain health more likely to stay physically active?

Psychologist Kirk Erickson and his colleagues (2011) set out to answer this question by designing an experiment to test whether aerobic exercise could improve brain health and cognitive functioning in older adults who were in good physical health but otherwise sedentary. And by sedentary, they meant sedentary: One requirement for participating in the study was that the participant had not been physically active for more than 30 minutes in the past six months.

The 120 participants, aged 55 to 80, were randomly assigned to two groups that met three times a week for a year. The stretching and toning group attended classes where they engaged in nonaerobic exercise, including muscle-

The aerobic exercise group started slowly. They began by walking around a track for just 10 minutes a session. Every week, the time spent walking was increased by just 5 minutes. By week 7, the participants were walking 40 minutes per session, three times a week.

What were the findings? After a year of regular exercise, both groups improved on measures of spatial memory, which is good news for those who engage in less-

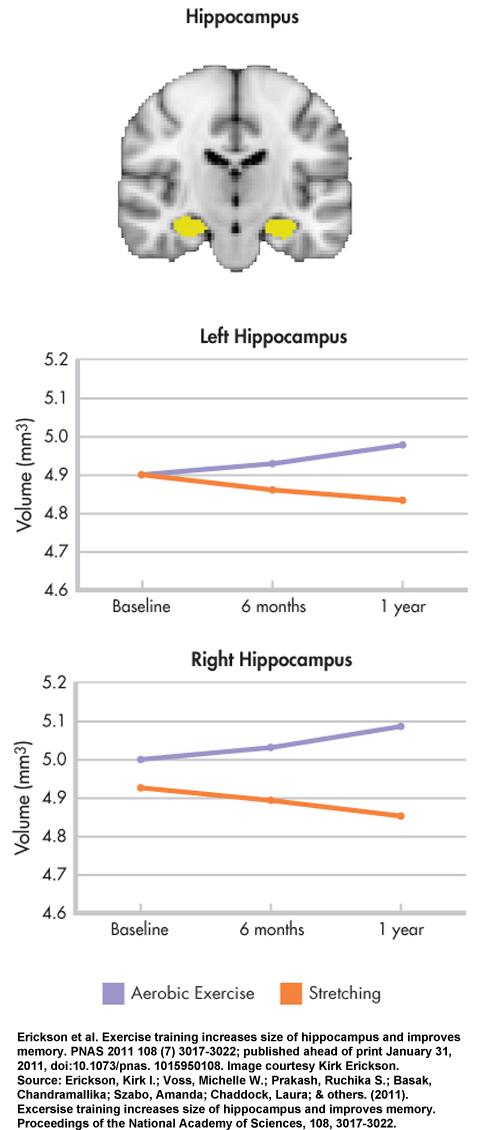

Were there any structural effects on the elderly brains? Because of its involvement in memory (see Chapter 6), researchers looked for changes in the hippocampus. The stretching and toning group showed, on average, a 1.4 percent decline in hippocampal volume over the one-

Source: Erickson, Kirk I.; Voss, Michelle W.; Prakash, Ruchika S.; Basak, Chandramallika; Szabo, Amanda; Chaddock, Laura; & others. (2011). Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 3017–

In contrast, participants in the aerobic exercise group increased the volume of their hippocampus by an average of 2 percent. Two percent may not sound like a large increase. However, because the hippocampus typically shrinks about 1-

This study is notable for several reasons. First, it showed that even in late adulthood, behavioral interventions can affect brain structure. Second, it showed that aerobic exercise is neuroprotective—

The bottom line: Declines in cognitive abilities and brain functions are neither inevitable nor unalterable (Voss & others, 2010). As Erickson (2011) points out, you don’t have to be a highly conditioned athlete to reap the benefits of aerobic exercise. You don’t need to join a gym, hire a trainer, or purchase expensive equipment. All you need is a good pair of shoes and a safe place to walk.

In contrast, the greatest intellectual declines tend to occur in older adults with unstimulating lifestyles, such as people who live alone, are dissatisfied with their lives, and engage in few activities (see Calero-

Social Development

One theory of social development in late adulthood holds that older adults gradually “disengage,” or withdraw, from vocational, social, and relationship roles as they face the prospect of their lives ending (Lange & Grossman, 2010). But consider your author Sandy’s father, Erv. Even after Erv was well into his 80s, he bowled in a league every Tuesday night and would join about a dozen other retired men in their 70s and 80s for lunch and a monthly poker game.

What Erv and his buddies epitomized is the activity theory of aging. According to the activity theory of aging, life satisfaction in late adulthood is highest when you maintain your previous level of activity, either by continuing old activities or by finding new ones (Lange & Grossman, 2010).

Just like younger adults, older adults differ in the level of activity they find personally optimal. Some older adults pursue a busy lifestyle of social activities, travel, college classes, and volunteer work. Other older adults are happier with a quieter lifestyle: reading, pursuing hobbies, or simply puttering around their homes. Such individual preferences reflect lifelong temperamental and personality qualities that continue to be evident as a person ages.

For many older adults, caregiving responsibilities can persist well into late adulthood. Sandy’s mother, Fern, for example, spent a great deal of time helping out with her young grandchildren and caring for some of her older relatives. She was not unusual in that respect. Many older adults who are healthy and active find themselves taking care of other older adults who are sick or have physical limitations.

Along with satisfying social relationships, the prescription for psychological well-

In contrast, those who are filled with regrets or bitterness about past mistakes, missed opportunities, or bad decisions experience despair—a deep sense of disappointment in life. Often the theme of ego integrity versus despair emerges as older adults engage in a life review, thinking about or retelling their life story to others (Bohlmeijer & others, 2007; Kunz & Soltys, 2007).

Test your understanding of Adulthood with  .

.