Industrial (Personnel) Psychology

Three major goals of personnel psychologists are selecting the best applicants for jobs, training employees so that they perform their jobs effectively, and accurately evaluating employee performance. The first step in attaining each of these goals is to perform a job analysis.

Job Analysis

When job descriptions are lacking or inaccurate, employers and employees may experience frustration as tasks are confused and positions are misunderstood or even duplicated. Consequently, I/O psychologists are called upon to conduct job analyses that result in accurate job descriptions, benefiting everyone involved. Outdated or inflated job descriptions may land organizations in legal hot water. More specifically, a job description that indicates more knowledge, skill, or ability than is actually needed to perform well in a job could violate the Americans with Disabilities Act. For example, sewing straight seams may be determined more by one’s sense of touch than by perfect vision; thus, if a garment manufacturer required sewing machine operators to have perfect vision, then visually impaired people—

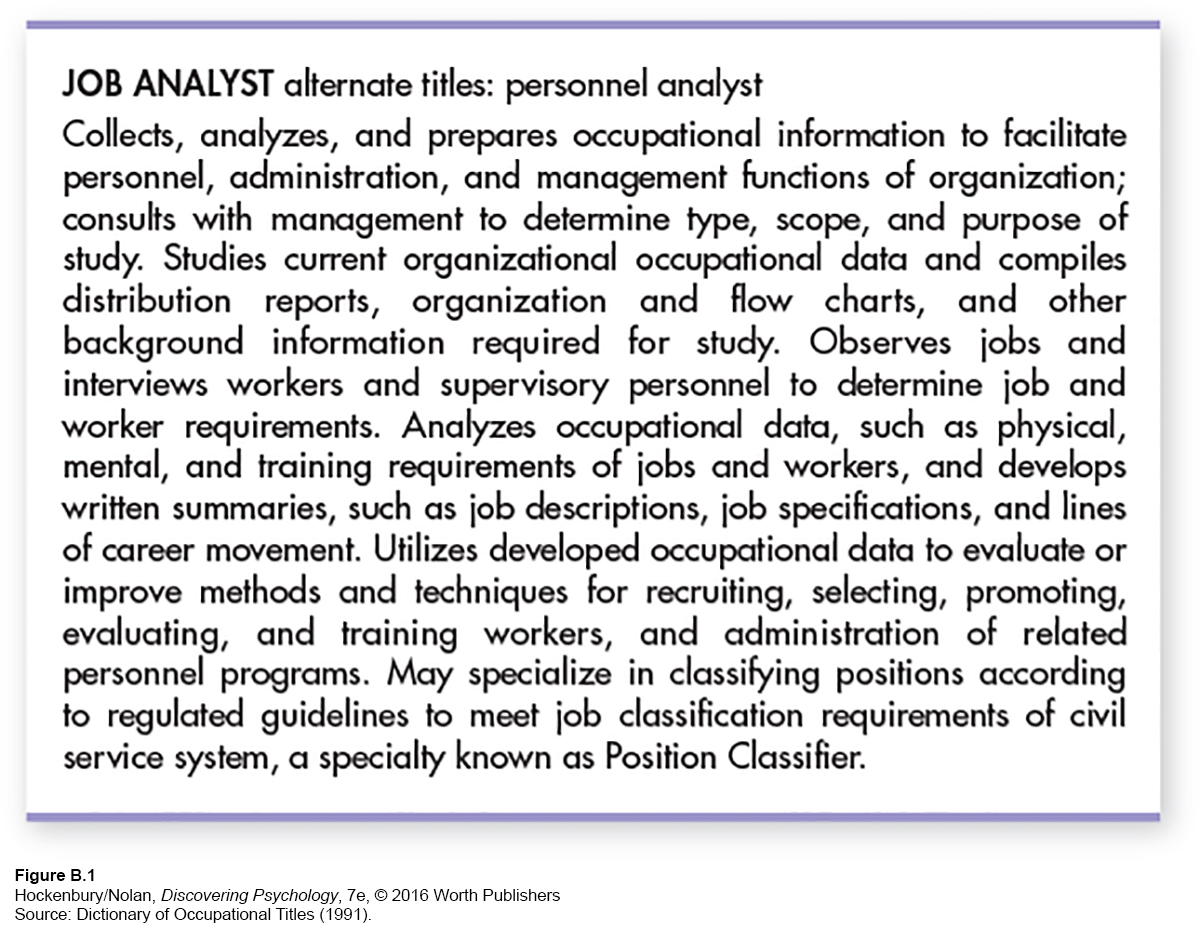

Job analysis is a technique that identifies the major responsibilities of a job, along with the human characteristics needed to fill it. Someone performing a job analysis may observe employees at work, interview them, or ask them to complete surveys regarding major job duties and tasks. This information is then used to create or revise job descriptions, such as the example given in Figure B.1. Sometimes this information can even be used to restructure an organization. Why should an employer invest in this process? When job analysis is the foundation of recruitment, training, and performance management systems, these systems have a better chance of reducing turnover and improving productivity and morale (Felsberg, 2004).

Job analysis is also important for designing effective training programs. In 2007, U.S. organizations spent over $58.5 billion on training programs for their employees (Training, 2007). I/O psychologists can assist organizations in creating customized and effective training programs that integrate job analysis data with organizational goals. Modern training programs should include collaborative and on-

Finally, job analysis is useful in designing performance appraisal systems. Job analysis defines and clarifies job competencies so that performance appraisal instruments may be developed and training results can be assessed. This process helps managers make their expectations and ratings clear and easy to understand. As more companies realize the benefits of job analysis, they will call upon I/O psychologists to design customized performance management systems to better track and communicate employee performance.

A Closer Look at Personnel Selection

Whether you are looking for a job or trying to fill a position at your company, it’s helpful to understand the personnel selection process. The more you know about how selection decisions are made, the more likely you are to find a job that fits your needs, skills, and interests—

The goal in personnel selection is to hire only those applicants who will perform the job effectively. There are many selection devices available for the screening process, including psychological tests, work samples, and selection interviews. With so many devices available, each with strengths and weaknesses, personnel psychologists are often called upon to recommend those devices that might best be used in a particular selection process. Consequently, they must consider selection device validity, the extent to which a selection device is successful in distinguishing between those applicants who will become high performers and those who will not.

PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTS

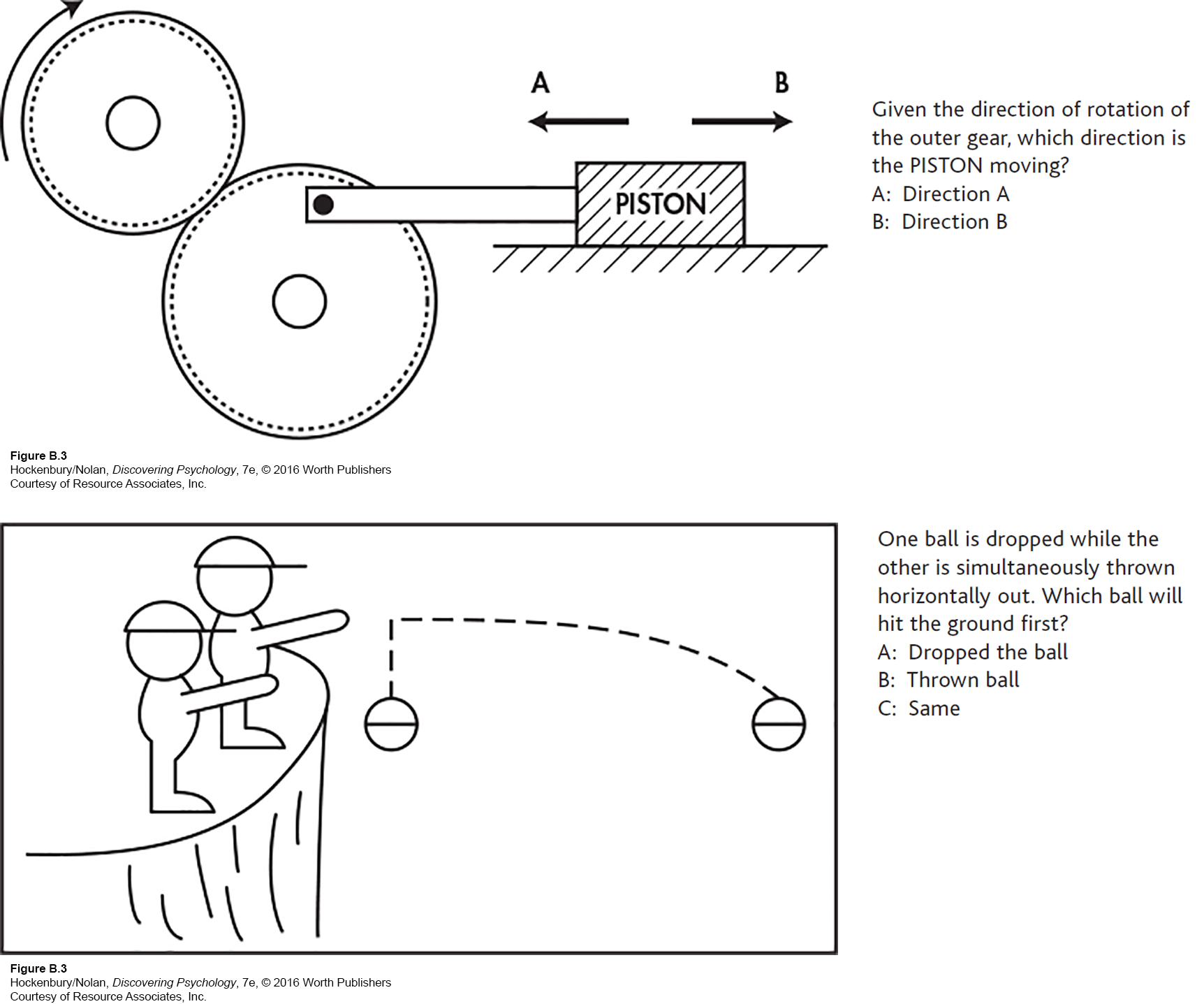

Charles Wonderlic, president of the Wonderlic Testing Firm and grandson of the founder, explains why psychological tests are so frequently used in the selection process: “To make better hiring and managing decisions that reduce turnover and improve sales, many store owners add personality profiling tools and other tests to their hiring process because it offers recruiters insight into candidates’ traits they may not have even thought to explore” (Wonderlic, 2005). A survey of Fortune 1000 firms (n = 151) found that 28 percent of employer respondents use honesty/integrity tests, 22 percent screen for violence potential, and 20 percent screen for personality (Piotrowski & Armstrong, 2006). The survey also reveals that up to a third of employers may soon include online testing as a part of their screening process. Employers want quick, inexpensive, and accurate ways to identify whether applicant qualifications, aptitudes, and personality traits match the position requirements. Common types of psychological tests are integrity/honesty tests, cognitive ability tests, mechanical aptitude tests, motor and sensory ability tests, and personality tests.

Let’s first examine the popularity of integrity tests, which came about largely because of legislation limiting the use of polygraph tests in the workplace. According to the 2007 National Retail Security Survey (Hollinger & Adams, 2007), employee theft accounted for approximately half of all retail losses, at $19.5 billion—

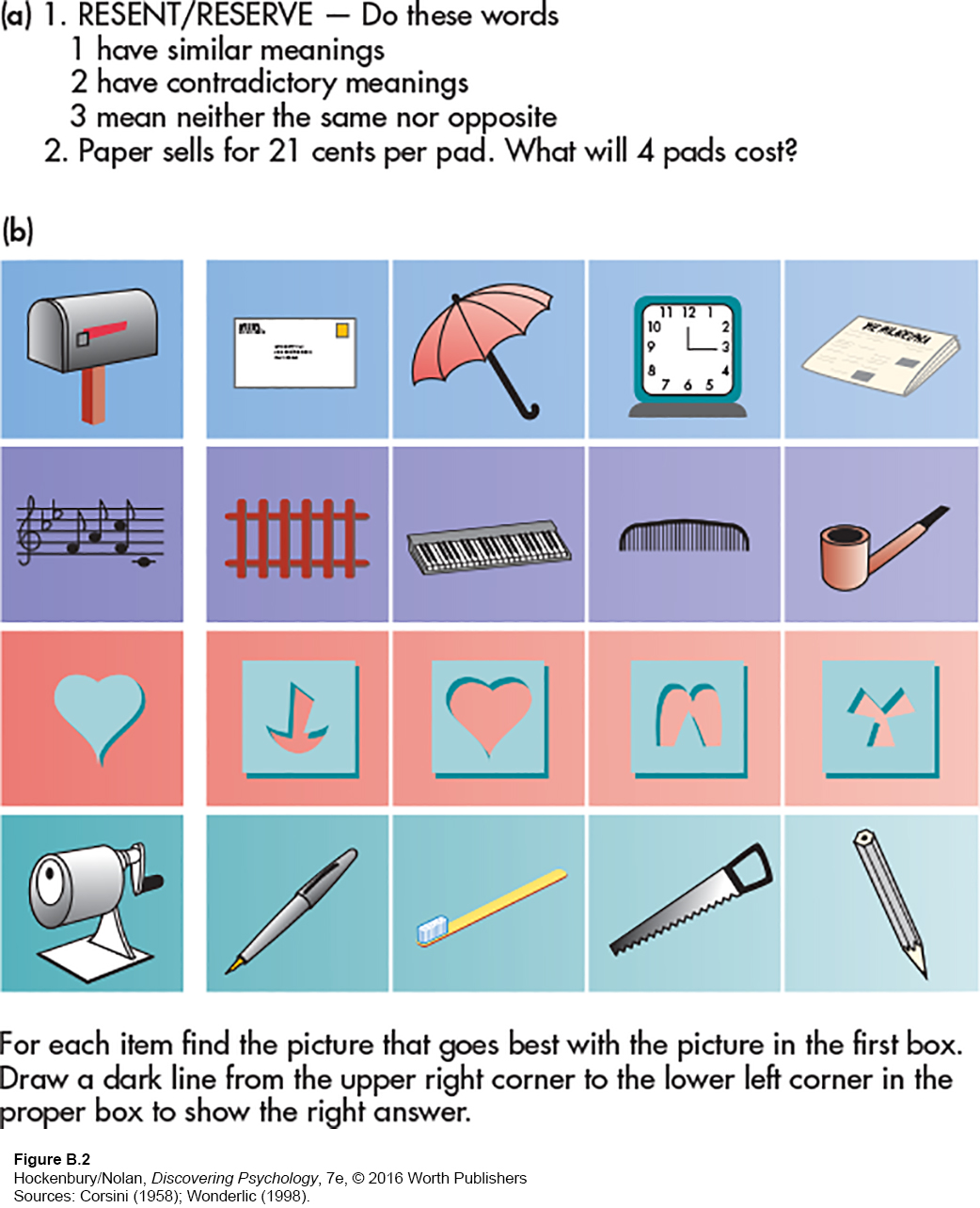

Cognitive ability tests measure general intelligence or specific cognitive skills, such as mathematical or verbal ability. The Wonderlic Personnel Test–

Personality tests are designed to measure either abnormal or normal personality characteristics. An assessment of abnormal personality characteristics might be appropriate for selecting people for sensitive jobs, such as nuclear power plant operator, police officer, or airline pilot. Tests designed to measure normal personality traits, however, are more popular for the selection of employees (Bates, 2002). Tests based on the Big Five Model allow employers to identify traits such as conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness (Bates, 2002). This information can also be used to understand employee motivation and enhance team building and team placement.

WORK SAMPLES AND SITUATIONAL EXERCISES

Two other kinds of personnel selection devices are work samples and situational exercises. Work samples are typically used for jobs involving the manipulation of objects, while situational exercises are usually used for jobs involving managerial or professional skills. Work samples have been called “high-

At Toyota, applicants must demonstrate their ability to read dials and gauges and spot safety problems in a virtual setting as a part of their “Computer Assembler Audition.” Quest Diagnostics is using online video previewing of jobs to educate potential applicants about the typical workday of a phlebotomist. This step helps reduce turnover. Finally, use of an online screening and assessment system allowed SunTrust Bank to shorten the previous two-

SELECTION INTERVIEWS

Great news! You passed the pre-

In contrast to unstructured interviews, structured behavioral interviews, if developed and conducted properly, are adequate predictors of job performance. A structured interview should be based on a job analysis, prepared in advance, standardized for all applicants, and evaluated by a panel of interviewers trained to record and rate the applicant’s responses using a numeric rating scale. When these criteria are met, the interview is likely to be an effective selection tool (Krohe, 2006).