The Psychoanalytic Perspective on Personality

KEY THEME

Freud’s psychoanalysis stresses the importance of unconscious forces, sexual and aggressive instincts, and early childhood experience.

KEY QUESTIONS

What were the key influences on Sigmund Freud’s thinking?

How are unconscious influences revealed?

What are the three basic structures of personality, and what are the defense mechanisms?

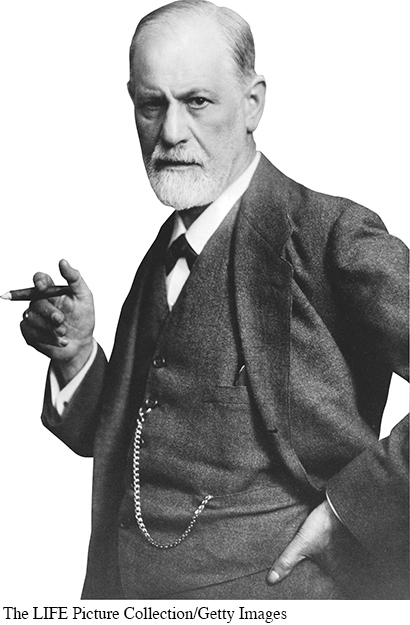

Sigmund Freud, one of the most influential figures of the twentieth century, was the founder of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis is a theory of personality that stresses the influence of unconscious mental processes, the importance of sexual and aggressive instincts, and the enduring effects of early childhood experience on personality. Because so many of Freud’s ideas have become part of our common culture, it is difficult to imagine just how radical he seemed to his contemporaries. The following biographical sketch highlights some of the important influences that shaped Freud’s ideas and theory.

The Life of Sigmund Freud

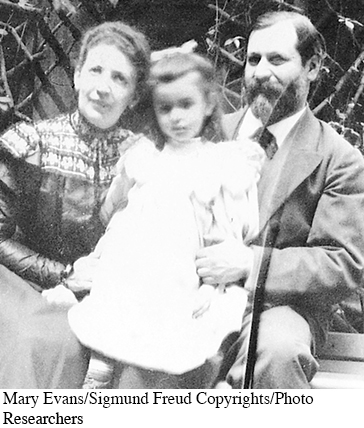

Sigmund Freud was born in 1856 in what is today Pribor, Czech Republic. When he was 4 years old, his family moved to Vienna, where he lived until the last year of his life.

Freud was extremely intelligent and intensely ambitious. He studied medicine, became a physician, and then proved himself to be an outstanding physiological researcher. Early in his career, Freud was among the first investigators of a new drug that had anesthetic and mood-

Prospects for an academic career in scientific research were very poor, especially for a Jew in Vienna, which was intensely anti-

INFLUENCES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF FREUD’S IDEAS

Freud’s theory evolved gradually during his first 20 years of private practice. He based his theory on observations of his patients as well as on self-

At first, Freud embraced Breuer’s technique, but he found that not all of his patients could be hypnotized. Eventually, Freud dropped the use of hypnosis and developed his own technique of free association to help his patients uncover forgotten memories. Freud’s patients would spontaneously report their uncensored thoughts, mental images, and feelings as they came to mind. From these “free associations,” the thread that led to the crucial long-

In 1900, Freud published what many consider his most important work, The Interpretation of Dreams. By the early 1900s, Freud had developed the basic tenets of his psychoanalytic theory and was no longer the isolated scientist. He was gaining international recognition and developing a following.

In 1904, Freud published what was to become one of his most popular books, The Psychopathology of Everyday Life. He described how unconscious thoughts, feelings, and wishes are often reflected in acts of forgetting, inadvertent slips of the tongue, accidents, and errors. By 1909, Freud’s influence was also felt in the United States, when he and other psychoanalysts were invited to lecture at Clark University in Massachusetts. For the next 30 years, Freud continued to refine his theory, publishing many books, articles, and lectures.

The last two decades of Freud’s life were filled with many personal tragedies. The terrible devastation of World War I weighed heavily on his mind. In 1920, one of his daughters died. In the early 1920s, Freud developed cancer of the jaw, a condition for which he would ultimately undergo more than 30 operations. And during the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Nazis were steadily gaining power in Germany.

Given the climate of the times, it’s not surprising that Freud came to focus on humanity’s destructive tendencies. For years he had asserted that sexuality was the fundamental human motive, but now he added aggression as a second powerful human instinct. During this period, Freud wrote Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), in which he applied his psychoanalytic perspective to civilization as a whole. The central theme of the book is that human nature and civilization are in basic conflict—

Freud’s extreme pessimism was undoubtedly a reflection of the destruction he saw all around him. By 1933, Adolf Hitler had seized power in Germany. Freud’s books were banned and publicly burned in Berlin. Five years later, the Nazis marched into Austria, seizing control of Freud’s homeland. Although Freud’s life was clearly threatened, it was only after his youngest daughter, Anna, had been detained and questioned by the Gestapo that Freud reluctantly agreed to leave Vienna. Under great duress, Freud moved his family to the safety of England. A year later, his cancer returned. In 1939, Freud died in London at the age of 83 (Gay, 2006).

This brief sketch cannot do justice to the richness of Freud’s life and the influence of his culture on his ideas. Today, Freud’s legacy continues to influence psychology, philosophy, literature, art, and psychotherapy (Merlino & others, 2008; O’Roark, 2007).

Freud’s Dynamic Theory of Personality

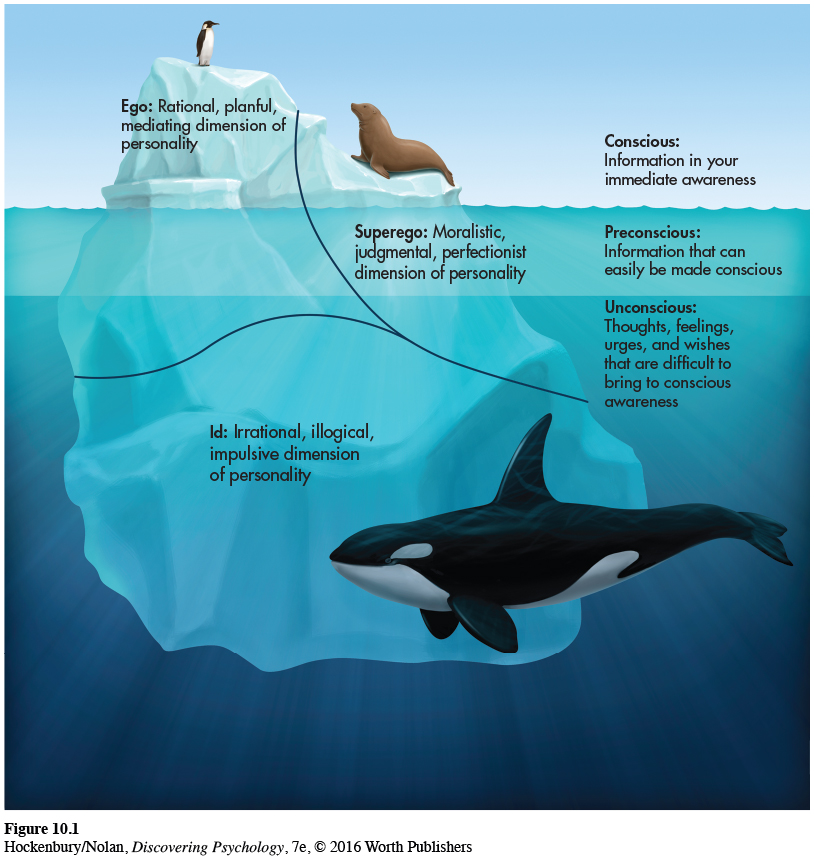

Freud (1940) saw personality and behavior as the result of a constant interplay among conflicting psychological forces. These psychological forces operate at three different levels of awareness: the conscious, the preconscious, and the unconscious. All the thoughts, feelings, and sensations that you’re aware of at this particular moment represent the conscious level. The preconscious contains information that you’re not currently aware of but can easily bring to conscious awareness, such as memories of recent events or your street address.

However, the conscious and preconscious are merely the visible tip of the iceberg of the mind. The bulk of this psychological iceberg is made up of the unconscious, which lies submerged below the waterline of the preconscious and conscious (see Figure 10.1 on the next page). You’re not directly aware of these submerged thoughts, feelings, wishes, and drives, but the unconscious exerts an enormous influence on your conscious thoughts and behavior.

Although it is not directly accessible, Freud (1904) believed that unconscious material often seeps through to the conscious level in distorted, disguised, or symbolic forms. Like a detective searching for clues, Freud carefully analyzed his patients’ reports of dreams and free associations for evidence of unconscious wishes, fantasies, and conflicts. Dream analysis was particularly important to Freud. “The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind,” he wrote in The Interpretation of Dreams (1900). Beneath the surface images, or manifest content, of a dream lies its latent content—the true, hidden, unconscious meaning that is disguised in the dream symbols (see Chapter 4).

Freud (1904, 1933) believed that the unconscious can also be revealed in unintentional actions, such as accidents, mistakes, instances of forgetting, and inadvertent slips of the tongue, which are often referred to as “Freudian slips.”

THE STRUCTURE OF PERSONALITY

According to Freud (1933), each person possesses a certain amount of psychological energy. This psychological energy develops into the three basic structures of personality—

The id, the most primitive part of the personality, is entirely unconscious and present at birth. The id is completely immune to logic, values, morality, danger, and the demands of the external world. It is the original source of psychological energy, parts of which will later evolve into the ego and superego (Freud, 1933, 1940).

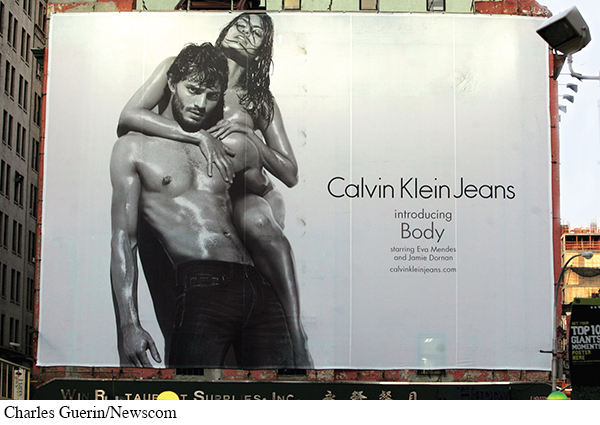

The id is connected to the biological urges that perpetuate the existence of the individual and the species—

The id is ruled by the pleasure principle—the relentless drive toward immediate satisfaction of the instinctual urges, especially sexual urges (Freud, 1920). Thus, the id strives to increase pleasure, reduce tension, and avoid pain. Even though it operates unconsciously, Freud saw the pleasure principle as the most fundamental human motive.

Equipped only with the id, the newborn infant is completely driven by the pleasure principle. When cold, wet, hungry, or uncomfortable, the newborn wants his needs addressed immediately. As the infant gains experience with the external world, however, he learns that his caretakers can’t or won’t always immediately satisfy those needs.

Thus, a new dimension of personality develops from part of the id’s psychological energy—

As the young child gains experience, she gradually learns acceptable ways to satisfy her desires and instincts, such as waiting her turn rather than pushing another child off a playground swing. Hence, the ego is the pragmatic part of the personality that learns various compromises to reduce the tension of the id’s instinctual urges. If the ego can’t identify an acceptable compromise to satisfy an instinctual urge, such as a sexual urge, it can repress the impulse, or remove it from conscious awareness (Freud, 1915a).

In early childhood, the ego must deal with external parental demands and limitations. Implicit in those demands are the parents’ values and morals, their ideas of the right and wrong ways to think, act, and feel. Eventually, the child encounters other advocates of society’s values, such as teachers and religious and legal authorities (Freud, 1926). Gradually, these social values move from being externally imposed demands to being internalized rules and values.

By about age 5 or 6, the young child has developed an internal, parental voice that is partly conscious—

THE EGO DEFENSE MECHANISMS

UNCONSCIOUS SELF-

The ego has a difficult task. It must be strong, flexible, and resourceful to successfully mediate conflicts among the instinctual demands of the id, the moral authority of the superego, and external restrictions. According to Freud (1923), everyone experiences an ongoing daily battle among these three warring personality processes.

When the demands of the id or superego threaten to overwhelm the ego, anxiety results (Freud, 1915b). If instinctual id impulses overpower the ego, a person may act impulsively and perhaps destructively. Using Freud’s terminology, you could say that Julian’s id was out of control when he stole from the church and tried to rob the drugstore. In contrast, if superego demands overwhelm the ego, an individual may suffer from guilt, self-

If a realistic solution or compromise is not possible, the ego may temporarily reduce anxiety by distorting thoughts or perceptions of reality through processes that Freud called ego defense mechanisms (A. Freud, 1946; Freud, 1915c). By resorting to these largely unconscious self-

The most fundamental ego defense mechanism is repression (Freud, 1915a, 1936). To some degree, repression occurs in every ego defense mechanism. In simple terms, repression is unconscious forgetting. Anxiety-

Repression, however, is not an all-

This is what occurs with the ego defense mechanism of displacement. Displacement occurs when emotional impulses are redirected to a substitute object or person, usually one less threatening or dangerous than the original source of conflict (A. Freud, 1946). For example, an employee angered by a supervisor’s unfair treatment may displace his hostility onto family members when he comes home from work. The employee consciously experiences anger but directs it toward someone other than its true target, which remains unconscious.

Freud (1930) believed that a special form of displacement, called sublimation, is largely responsible for the productive and creative contributions of people and even of whole societies. Sublimation involves displacing sexual urges toward “an aim other than, and remote from, that of sexual gratification” (Freud, 1914). In effect, sublimation channels sexual urges into productive, socially acceptable, nonsexual activities (Cohen & others, 2014).

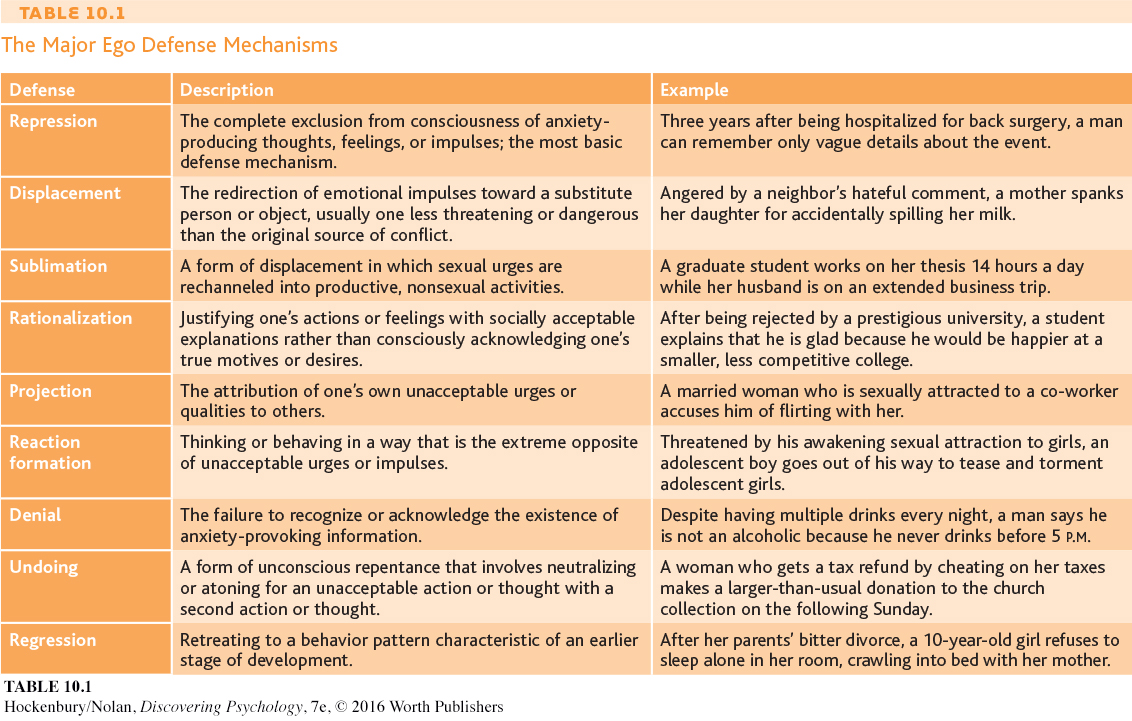

The major defense mechanisms are summarized in Table 10.1. In Freud’s view, the drawback to using any defense mechanism is that maintaining these self-

The use of defense mechanisms is very common. And, when ego defense mechanisms are used in limited areas and on a short-

Personality Development

THE PSYCHOSEXUAL STAGES

KEY THEME

The psychosexual stages are age-

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the five psychosexual stages, and what are the core conflicts of each stage?

What is the consequence of fixation?

What role does the Oedipus complex play in personality development?

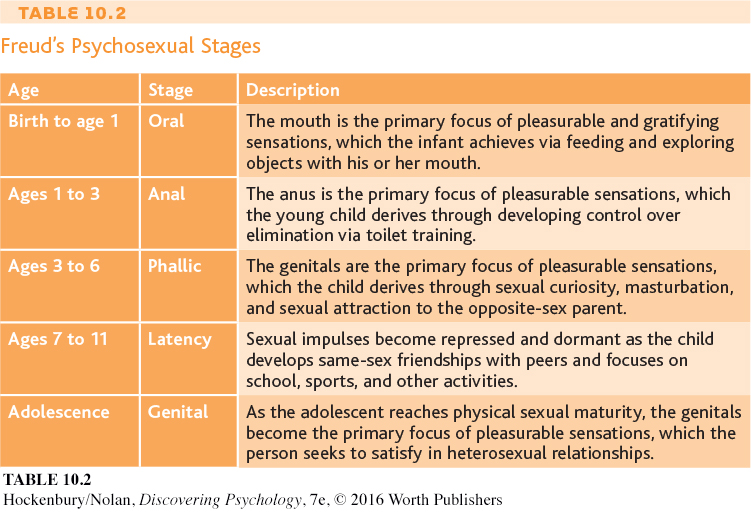

According to Freud (1905), people progress through five psychosexual stages of development. The foundations of adult personality are established during the first five years of life, as the child progresses through the oral, anal, and phallic psychosexual stages. The latency stage occurs during late childhood, and the fifth and final stage, the genital stage, begins in adolescence.

Each psychosexual stage represents a different focus of the id’s sexual energies. Freud (1940) contended that “sexual life does not begin only at puberty, but starts with clear manifestations after birth.” This statement is often misinterpreted. Freud was not saying that an infant experiences sexual urges in the same way that an adult does. Instead, Freud believed that the infant or young child expresses primitive sexual urges by seeking sensual pleasure from different areas of the body. Thus, the psychosexual stages are age-

Over the first five years of life, the expression of primitive sexual urges progresses from one bodily zone to another in a distinct order: the mouth, the anus, and the genitals. The first year of life is characterized as the oral stage. During this time the infant derives pleasure through the oral activities of sucking, chewing, and biting. During the next two years, pleasure is derived through elimination and acquiring control over elimination—

FIXATION

UNRESOLVED DEVELOPMENTAL CONFLICTS

At each psychosexual stage, Freud (1905) believed, the infant or young child is faced with a developmental conflict that must be successfully resolved in order to move on to the next stage. The heart of this conflict is the degree to which parents either frustrate or overindulge the child’s expression of pleasurable feelings. Hence, Freud (1940) believed that parental attitudes and the timing of specific child-

If frustrated, the child will be left with feelings of unmet needs characteristic of that stage. If overindulged, the child may be reluctant to move on to the next stage. In either case, the result of an unresolved developmental conflict is fixation at a particular stage. The person continues to seek pleasure through behaviors that are similar to those associated with that psychosexual stage. For example, the adult who constantly chews gum, smokes, or bites her fingernails may have unresolved oral psychosexual conflicts.

THE OEDIPUS COMPLEX

A PSYCHOSEXUAL DRAMA

The most critical conflict that the child must successfully resolve for healthy personality and sexual development occurs during the phallic stage (Freud, 1923, 1940). As the child becomes more aware of pleasure derived from the genital area, Freud believed, the child develops a sexual attraction to the opposite-

According to Freud, this attraction to the opposite-

To resolve the Oedipus complex and these anxieties, the little boy ultimately joins forces with his former enemy by resorting to the defense mechanism of identification. That is, he imitates and internalizes his father’s values, attitudes, and mannerisms. There is, however, one strict limitation in identifying with the father. Only the father can enjoy the sexual affections of the mother. This limitation becomes internalized as a taboo against incestuous urges in the boy’s developing superego, a taboo that is enforced by the superego’s use of guilt and societal restrictions (Freud, 1905, 1923).

Girls also ultimately resolve the Oedipus complex by identifying with the same-

According to Freud (1940), the little girl blames her mother for “sending her into the world so insufficiently equipped.” Thus, she develops contempt for and resentment toward her mother. However, in her attempt to take her mother’s place with her father, she also identifies with her mother. Like the little boy, the little girl internalizes the attributes of the same-

Freud’s views on female sexuality, particularly the concept of penis envy, are among his most severely criticized ideas. Perhaps recognizing that his explanation of female psychosexual development rested on shaky ground, Freud (1926) admitted, “We know less about the sexual life of little girls than of boys. But we need not feel ashamed of this distinction. After all, the sexual life of adult women is a ‘dark continent’ for psychology.”

THE LATENCY AND GENITAL STAGES

It often happens that a young man falls in love seriously for the first time with a mature woman, or a girl with an elderly man in a position of authority; this is a clear echo of the [earlier] phase of development that we have been discussing, since these figures are able to re-

—Sigmund Freud (1905)

Freud felt that because of the intense anxiety associated with the Oedipus complex, the sexual urges of boys and girls become repressed during the latency stage in late childhood. Outwardly, children in the latency stage express a strong desire to associate with same-

The final resolution of the Oedipus complex occurs in adolescence, during the genital stage. As incestuous urges start to resurface, they are prohibited by the moral ideals of the superego as well as by societal restrictions. Thus, the person directs sexual urges toward socially acceptable substitutes, who often resemble the person’s opposite-

In Freud’s theory, a healthy personality and sense of sexuality result when conflicts are successfully resolved at each stage of psychosexual development (summarized in Table 10.2). Successfully negotiating the conflicts at each psychosexual stage results in the person’s capacity to love and in productive living through one’s work, child rearing, and other accomplishments.

The Neo-Freudians

FREUD’S DESCENDANTS AND DISSENTERS

KEY THEME

The neo-

KEY QUESTIONS

How did the neo-

Freudians generally depart from Freud’s ideas? What were the key ideas of Jung, Horney, and Adler?

What are three key criticisms of Freud’s theory and of the psychoanalytic perspective?

Freud’s ideas were always controversial. But by the early 1900s, he had attracted a number of followers, many of whom went to Vienna to study with him. Although these early followers developed their own personality theories, they still recognized the importance of many of Freud’s basic notions, such as the influence of unconscious processes and early childhood experiences. In effect, they kept the foundations that Freud had established but offered new explanations for personality processes. Hence, these theorists are often called neo-

In general, the neo-

In Chapter 9 on lifespan development, we described the psychosocial theory of one famous neo-

CARL JUNG

ARCHETYPES AND THE COLLECTIVE UNCONSCIOUS

What we properly call instincts are physiological urges, and are perceived by the senses. But at the same time, they also manifest themselves in fantasies and often reveal their presence only by symbolic images. These manifestations are what I call the archetypes. They are without known origin; and they reproduce themselves in any time or in any part of the world.

—Carl Jung (1964)

Born in a small town in Switzerland, Carl Jung (1875–

Intrigued by Freud’s ideas, Jung began a correspondence with him. At their first meeting, the two men were so compatible that they talked for 13 hours nonstop. Freud felt that his young disciple was so promising that he called him his “adopted son” and his “crown prince.” It would be Jung, Freud decided, who would succeed him and lead the international psychoanalytic movement. However, Jung was too independent to relish his role as Freud’s unquestioning disciple. As Jung continued to put forth his own ideas, his close friendship with Freud ultimately ended in bitterness (Solomon, 2003).

Jung rejected Freud’s belief that human behavior is fueled by the instinctual drives of sex and aggression. Instead, Jung believed that people are motivated by a more general psychological energy that pushes them to achieve psychological growth, self-

In studying different cultures, Jung was struck by the universality of many images and themes, which also surfaced in his patients’ dreams and preoccupations. These observations led to some of Jung’s most intriguing ideas, the notions of the collective unconscious and archetypes.

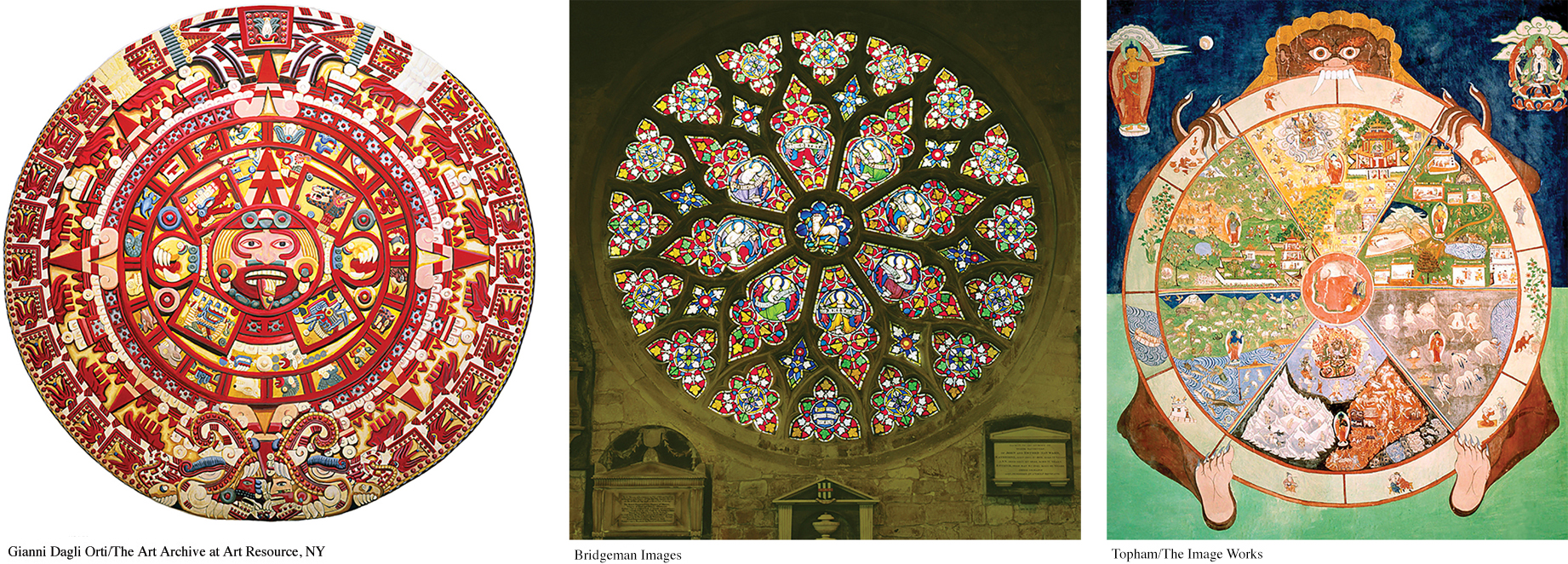

Jung (1936) believed that the deepest part of the individual psyche is the collective unconscious, which is shared by all people and reflects humanity’s collective evolutionary history. He described the collective unconscious as containing “the whole spiritual heritage of mankind’s evolution, born anew in the brain structure of every individual” (Jung, 1931).

Contained in the collective unconscious are the archetypes, the mental images of universal human instincts, themes, and preoccupations (Jung, 1964). Common archetypal themes that are expressed in virtually every culture are the hero, the powerful father, the nurturing mother, the witch, the wise old man, the innocent child, and death and rebirth.

Not surprisingly, Jung’s concepts of the collective unconscious and shared archetypes have been criticized as being unscientific or mystical. As far as we know, individual experiences cannot be genetically passed down from one generation to the next. Regardless, Jung’s ideas make more sense if you think of the collective unconscious as reflecting shared human experiences. The archetypes, then, can be thought of as symbols that represent the common, universal themes of the human life cycle. These universal themes include birth, achieving a sense of self, parenthood, the spiritual search, and death.

Although Jung’s theory never became as influential as Freud’s, some of his ideas have gained wide acceptance. For example, Jung (1923) was the first to describe two basic personality types: introverts, who focus their attention inward, and extraverts, who turn their attention and energy toward the outside world. We will encounter these two basic personality dimensions again when we look at trait theories later in this chapter. Finally, Jung’s emphasis on the drive toward psychological growth and self-

KAREN HORNEY

BASIC ANXIETY AND “WOMB ENVY”

Trained as a Freudian psychoanalyst, Karen Horney (1885–

Horney also stressed the importance of social relationships, especially the parent–

Man, [Freud] postulated, is doomed to suffer or destroy. . . . My own belief is that man has the capacity as well as the desire to develop his potentialities and become a decent human being, and that these deteriorate if his relationship to others and hence to himself is, and continues to be, disturbed. I believe that man can change and go on changing as long as he lives.

—Karen Horney (1945)

Horney (1945) described three patterns of behavior that the individual uses to defend against basic anxiety: moving toward, against, or away from other people. Those who move toward other people have an excessive need for approval and affection. Those who move against others have an excessive need for power, especially power over other people. They are often competitive, critical, and domineering, and they need to feel superior to others. Finally, those who move away from other people have an excessive need for independence and self-

Horney contended that people with a healthy personality are flexible in balancing these different needs, for there are times when each behavior pattern is appropriate. As Horney (1945) wrote, “One should be capable of giving in to others, of fighting, and keeping to oneself. The three can complement each other and make for a harmonious whole.” But when one pattern becomes the predominant way of dealing with other people and the world, psychological conflict and problems can result.

Horney also sharply disagreed with Freud’s interpretation of female development, especially his notion that women suffer from penis envy. What women envy in men, Horney (1926) claimed, is not their penis, but their superior status in society. In fact, Horney contended that men often suffer womb envy, envying women’s capacity to bear children. Neatly standing Freud’s view of feminine psychology on its head, Horney argued that men compensate for their relatively minor role in reproduction by constantly striving to make creative achievements in their work (Gilman, 2001). As Horney (1945) wrote, “Is not the tremendous strength in men of the impulse to creative work in every field precisely due to their feelings of playing a relatively small part in the creation of living beings, which constantly impels them to an overcompensation in achievement?”

Horney shared Jung’s belief that people are not doomed to psychological conflict and problems. Also like Jung, Horney believed that the drive to grow psychologically and achieve one’s potential is a basic human motive.

ALFRED ADLER

FEELINGS OF INFERIORITY AND STRIVING FOR SUPERIORITY

To be a human being means to have inferiority feelings. One recognizes one’s own powerlessness in the face of nature. One sees death as the irrefutable consequence of existence. But in the mentally healthy person this inferiority feeling acts as a motive for productivity, as a motive for attempting to overcome obstacles, to maintain oneself in life.

—Alfred Adler (1933a)

Born in Vienna, Alfred Adler (1870–

Adler (1933b) believed that the most fundamental human motive is striving for superiority—the desire to improve oneself, master challenges, and move toward self-

However, when people are unable to compensate for specific weaknesses or when their feelings of inferiority are excessive, they can develop an inferiority complex—a general sense of inadequacy, weakness, and helplessness. People with an inferiority complex are often unable to strive for mastery and self-

At the other extreme, people can overcompensate for their feelings of inferiority and develop a superiority complex. Behaviors caused by a superiority complex might include exaggerating one’s accomplishments and importance in an effort to cover up weaknesses and denying the reality of one’s limitations (Adler, 1954).

Like Horney, Adler believed that humans were motivated to grow and achieve their personal goals. And, like Horney, Adler emphasized the importance of cultural influences and social relationships (Carlson & others, 2008; West & Bubenzer, 2012).

Evaluating Freud and the Psychoanalytic Perspective on Personality

Like it or not, Sigmund Freud’s ideas have had a profound and lasting impact on our culture and on our understanding of human nature (see Merlino & others, 2008). Today, opinions on Freud span the entire spectrum. Some see him as a genius who discovered brilliant, lasting insights into human nature. Others contend that Freud was a deeply neurotic, driven man who successfully foisted his twisted personal view of human nature onto an unsuspecting public (Crews, 1984, 1996, 2006).

The truth, as you might suspect, lies somewhere in between. Although Freud has had an enormous impact on psychology and on society, there are several valid criticisms of Freud’s theory and, more generally, of the psychoanalytic perspective. We’ll discuss three of the most important problems next.

INADEQUACY OF EVIDENCE

Freud’s theory relies wholly on data derived from his relatively small number of patients and from self-

Furthermore, it is impossible to objectively assess Freud’s “data.” Freud did not take notes during his private therapy sessions. And, of course, when Freud did report a case in detail, it was still his own interpretation of the case that was recorded. For Freud, proof of the validity of his ideas depended on his uncovering similar patterns in different patients. So the critical question is this: Was Freud imposing his own ideas onto his patients, seeing only what he expected to see? Some critics think so (see Grünbaum, 2006, 2007).

LACK OF TESTABILITY

For good or ill, Sigmund Freud, more than any other explorer of the psyche, has shaped the mind of the 20th century. The very fierceness and persistence of his detractors are a wry tribute to the staying power of Freud’s ideas.

—Peter Gay (1999)

Many psychoanalytic concepts are so vague and ambiguous that they are impossible to objectively measure or confirm (Crews, 2006; Grünbaum, 2006). For example, how might you go about proving the existence of the id or the superego? Or how could you operationally define and measure the effects of the pleasure principle, the life instinct, or the Oedipus complex?

Psychoanalytic “proof” often has a “heads I win, tails you lose” style to it. In other words, psychoanalytic concepts are often impossible to dis prove because even seemingly contradictory information can be used to support Freud’s theory. For example, if your memory of childhood doesn’t jibe with Freud’s description of the psychosexual stages or the Oedipus complex, well, that’s because you’ve repressed it. Freud himself was not immune to this form of reasoning (Robinson, 1993). When one of Freud’s patients reported dreams that didn’t seem to reveal a hidden wish, Freud interpreted the dreams as betraying the patient’s hidden wish to disprove Freud’s dream theory!

Step by step, we are learning that Freud has been the most overrated figure in the entire history of science and medicine—

—Frederick Crews (2006)

As Freud acknowledged, psychoanalysis is better at explaining past behavior than at predicting future behavior (Gay, 1989). Indeed, psychoanalytic interpretations are so flexible that a given behavior can be explained by any number of completely different motives. For example, a man who is extremely affectionate toward his wife might be exhibiting displacement of a repressed incestuous urge (he is displacing his repressed affection for his mother onto his wife), reaction formation (he actually hates his wife intensely, so he compensates by being overly affectionate), or fixation at the oral stage (he is overly dependent on his wife).

Nonetheless, several key psychoanalytic ideas have been substantiated by empirical research (Cogan & others, 2007; Westen, 1990, 1998). Among these are the ideas that: (1) much of mental life is unconscious; (2) early childhood experiences have a critical influence on interpersonal relationships and psychological adjustment; and (3) people differ significantly in the degree to which they are able to regulate their impulses, emotions, and thoughts toward adaptive and socially acceptable ends.

SEXISM

Many people feel that Freud’s theories reflect a sexist view of women. Because penis envy produces feelings of shame and inferiority, Freud (1925) claimed, women are more vain, masochistic, and jealous than men. He also believed that women are more influenced by their emotions and have a lesser ethical and moral sense than men.

As Horney and other female psychoanalysts have pointed out, Freud’s theory uses male psychology as a prototype. Women are essentially viewed as a deviation from the norm of masculinity (Horney, 1926; Thompson, 1950). Perhaps, Horney suggested, psychoanalysis would have evolved an entirely different view of women if it were not dominated by the male point of view.

To Freud’s credit, women were quite active in the early psychoanalytic movement. Several female analysts became close colleagues of Freud (Freeman & Strean, 1987; Roazen, 1999, 2000). And, it was Freud’s daughter Anna, rather than any of his sons, who followed in his footsteps as an eminent psychoanalyst. Ultimately, Anna Freud became her father’s successor as leader of the international psychoanalytic movement.

The weaknesses in Freud’s theory and in the psychoanalytic approach to personality are not minor problems. As you’ll see in Chapter 14 on therapies, very few psychologists practice Freudian psychoanalysis today. All the same, Freud made some extremely significant contributions to modern psychological thinking. Most important, he drew attention to the existence and influence of mental processes that occur outside conscious awareness, an idea that continues to be actively investigated by today’s psychological researchers.

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that most psychologists today agree with Sigmund Freud’s personality theory?

Test your understanding of Personality and the Psychoanalytic Perspective with  .

.