The Social Cognitive Perspective on Personality

KEY THEME

The social cognitive perspective stresses conscious thought processes, self-

KEY QUESTIONS

What is the principle of reciprocal determination?

What is the role of self-

efficacy beliefs in personality? What are the key strengths and weaknesses of the social cognitive perspective?

Have you ever noticed how different your behavior and sense of self can be in different situations? Consider this example: You feel pretty confident as you enter your college algebra class. After all, you’re pulling an A, and your prof nods approvingly every time you participate in class, which you do frequently. In contrast, your English composition class is a disaster. You’re worried about passing the course, and you feel so shaky about your writing skills that you’re afraid to even ask a question, much less participate in class. Even a casual observer would notice how differently you behave in the two different situations—

The idea that a person’s conscious thought processes in different situations strongly influence his or her actions is one important characteristic of the social cognitive perspective on personality (Cervone & others, 2011). According to the social cognitive perspective, people actively process information from their social experiences. This information influences their goals, expectations, beliefs, and behavior, as well as the specific environments they choose.

The social cognitive perspective differs from psychoanalytic and humanistic perspectives in several ways. First, rather than basing their approach on self-

Albert Bandura and Social Cognitive Theory

The capacity to exercise control over the nature and quality of life is the essence of humanness. Unless people believe they can produce desired results and forestall detrimental ones by their actions, they have little incentive to act or persevere in the face of difficulties.

—Albert Bandura (2001)

Although several contemporary personality theorists have embraced the social cognitive approach to explaining personality, probably the most influential is Albert Bandura (b. 1925). We examined Bandura’s classic research on observational learning in Chapter 8, we encountered Bandura’s more recent research on self-

As Bandura’s early research demonstrated, we learn many behaviors by observing, and then imitating, the behavior of other people. But, as Bandura (1997) has pointed out, we don’t merely observe people’s actions. We also observe the consequences that follow people’s actions, the rules and standards that apply to behavior in specific situations, and the ways in which people regulate their own behavior. Thus, environmental influences are important, but conscious, self-

For example, consider your own goal of getting a college education. No doubt many social and environmental factors influenced your decision. In turn, your conscious decision to attend college determines many aspects of your current behavior, thoughts, and emotions. And your goal of attending college classes determines which environments you choose.

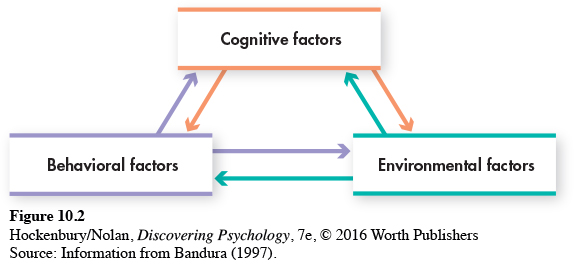

Bandura (1986, 1997) explains human behavior and personality as being caused by the interaction of behavioral, cognitive, and environmental factors. He calls this process reciprocal determinism (see Figure 10.2). According to this principle, each factor both influences the other factors and is influenced by the other factors. Thus, in Bandura’s view, our environment influences our thoughts and actions, our thoughts influence our actions and the environments we choose, our actions influence our thoughts and the environments we choose, and so on in a circular fashion.

BELIEFS OF SELF-

Collectively, a person’s cognitive skills, abilities, and attitudes represent the person’s self-

The most effective way of developing a strong sense of efficacy is through mastery experiences. Successes build a robust belief in one’s efficacy. Failures undermine it. A second way is through social modeling. If people see others like themselves succeed by sustained effort, they come to believe that they, too, have the capacity to do so. Social persuasion is a third way of strengthening people’s beliefs in their efficacy. If people are persuaded that they have what it takes to succeed, they exert more effort than if they harbor self-

—Albert Bandura (2004b)

For example, suppose you were faced with the problem of filling out paperwork for financial aid. Your sense of self-

However, our self-

We can acquire new behaviors and strengthen our beliefs of self-

From very early in life, children develop feelings of self-

Evaluating the Social Cognitive Perspective on Personality

A key strength of the social cognitive perspective on personality is its grounding in empirical, laboratory research (Bandura, 2004a). The social cognitive perspective is built on research in learning, cognitive psychology, and social psychology, rather than on clinical impressions. And, unlike vague psychoanalytic and humanistic concepts, the concepts of social cognitive theory are scientifically testable—

However, some psychologists feel that the social cognitive approach to personality applies best to laboratory research. In the typical laboratory study, the relationships among a limited number of very specific variables are studied. In everyday life, situations are far more complex, with multiple factors converging to affect behavior and personality. Thus, an argument can be made that clinical data, rather than laboratory data, may be more reflective of human personality.

The social cognitive perspective also ignores unconscious influences, emotions, or conflicts. Some psychologists argue that the social cognitive theory focuses on very limited areas of personality—

Nevertheless, by emphasizing the reciprocal interaction of mental, behavioral, and situational factors, the social cognitive perspective recognizes the complex combination of factors that influence our everyday behavior. By emphasizing the important role of learning, especially observational learning, the social cognitive perspective offers a developmental explanation of human functioning that persists throughout one’s lifetime. Finally, by emphasizing the self-