Assessing Personality

PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTS

KEY THEME

Tests to measure and evaluate personality fall into two basic categories: projective tests and self-

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the most widely used personality tests, and how are they administered and interpreted?

What are some key strengths and weaknesses of projective tests and self-

report inventories?

When we discussed intelligence tests in Chapter 7, we described the characteristics of a good psychological test. Beyond intelligence tests, there are literally hundreds of psychological tests that can be used to assess abilities, aptitudes, interests, and personality (Spies & others, 2010). Any psychological test is useful insofar as it achieves two basic goals:

It accurately and consistently reflects a person’s characteristics on some dimension.

It predicts a person’s future psychological functioning or behavior.

In this section, we’ll look at the very different approaches used in the two basic types of personality tests—

Projective Tests

LIKE SEEING THINGS IN THE CLOUDS

Projective tests developed out of psychoanalytic approaches to personality. In the most commonly used projective tests, a person is presented with a vague image, such as an inkblot or an ambiguous scene, then asked to describe what she “sees” in the image. The person’s response is thought to be a projection of her unconscious conflicts, motives, psychological defenses, and personality traits. Notice that this idea is related to the defense mechanism of projection, which was described in Table 10.1 earlier in the chapter. The first projective test was the famous Rorschach Inkblot Test, published by Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach in 1921 (Hertz, 1992).

The Rorschach test consists of 10 cards, 5 that show black-

Numerous scoring systems exist for the Rorschach. Interpretation is based on such criteria as whether the person reports seeing animate or inanimate objects, human or animal figures, and movement, and whether the person deals with the whole blot or just fragments of it (Exner, 2007; Exner & Erdberg, 2005).

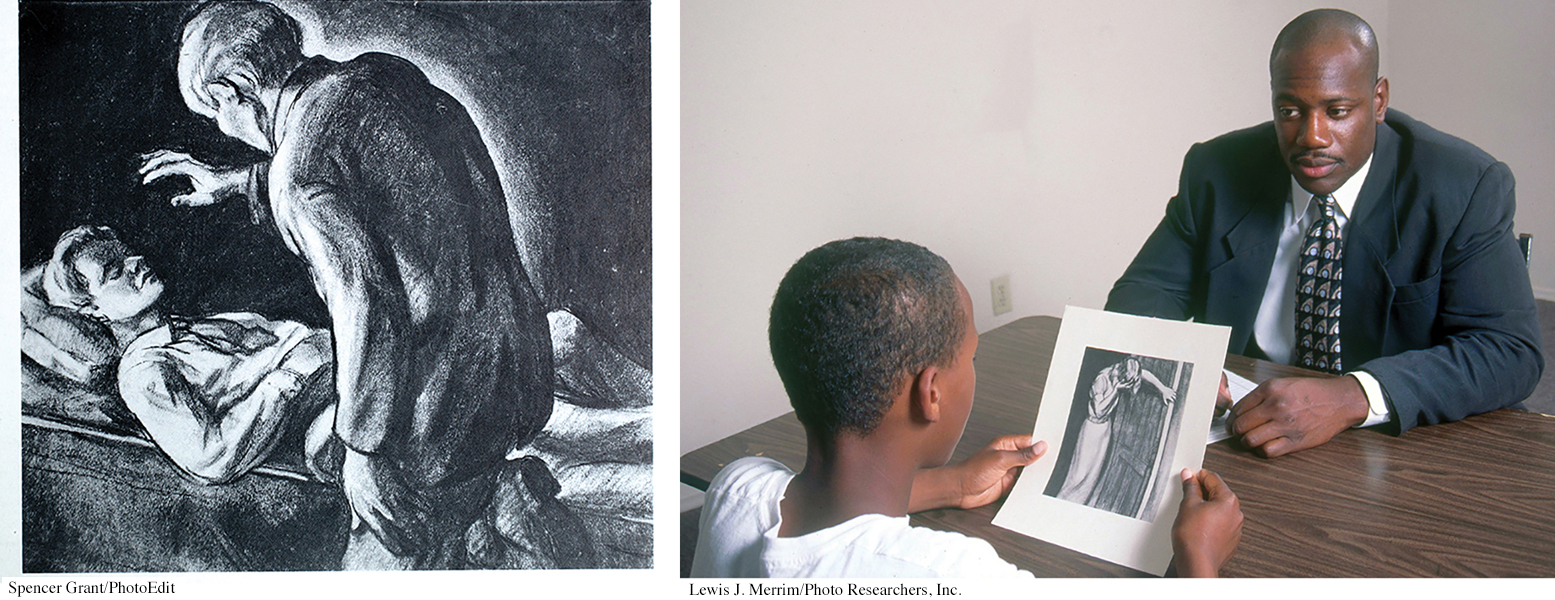

A more structured projective test is the Thematic Apperception Test, abbreviated TAT, which we discussed in Chapter 8. In the TAT, the person looks at a series of cards, each depicting an ambiguous scene. The person is asked to create a story about the scene, including what the characters are feeling and how the story turns out. The stories are scored for the motives, needs, anxieties, and conflicts of the main character and for how conflicts are resolved (Bellak, 1993; Langan-

SCIENCE VERSUS PSEUDOSCIENCE

Graphology: The “Write” Way to Assess Personality?

Does the way that you shape your d’s, dot your i’s, and cross your t’s reveal your true inner nature? That’s the basic premise of graphology, a pseudoscience that claims that your handwriting reveals your temperament, personality traits, intelligence, and reasoning ability. If that weren’t enough, graphologists also claim that they can accurately evaluate a job applicant’s honesty, reliability, leadership potential, ability to work with others, and so forth (Beyerstein, 2007; Beyerstein & Beyerstein, 1992).

Handwriting analysis is very popular throughout North America and Europe. There are dozens of graphology organizations around the world, each promoting its own specific methods of analyzing handwriting (Imberman & Rifkin, 2008). Many different types of agencies and institutions use graphology. For example, the CIA used graphology to help their agents recruit and manage spies until the early 2000s (Brandon, 2011).

Over the years, graphology has been especially popular in the business world, and it is still widely used in Europe, particularly in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom (Ellin, 2004). According to one estimate, over 80 percent of European companies use graphology in personnel matters (Greasley, 2000; see Simner & Goffin, 2003).

When subjected to scientific evaluation, how does graphology fare? Consider a study by Anthony Edwards and Peter Armitage (1992) that investigated graphologists’ ability to distinguish among people in three different groups:

Successful versus unsuccessful secretaries

Successful business entrepreneurs versus librarians and bank clerks

Actors and actresses versus monks and nuns

In designing their study, Edwards and Armitage enlisted the help of leading graphologists and incorporated their suggestions into the study design. The graphologists preapproved the study’s format and indicated that they felt it was a fair test of graphology. The graphologists also predicted they would have a high degree of success in discriminating among the people in each group. One graphologist stated that the graphologists would have close to a 100 percent success rate. Remember that prediction.

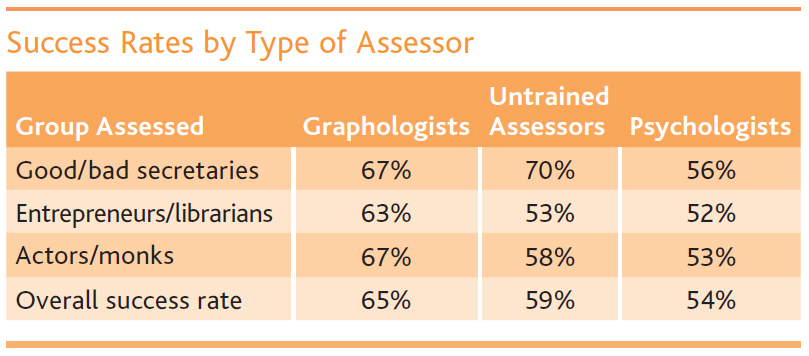

The three groups—

Four leading graphologists independently evaluated the handwriting samples. For each group, the graphologists tried to assign each handwriting sample to one category or the other. Two control measures were built into the study: (1) The handwriting samples were also analyzed by four ordinary people with no formal training in graphology or psychology; and (2) a typewritten transcript of the handwriting samples was evaluated by four psychologists. The psychologists made their evaluations on the basis of the content of the transcripts rather than on the handwriting itself.

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that handwriting analysis provides insights into your personality and predicts occupational success?

In the accompanying table, you can see how well the graphologists fared as compared to the untrained evaluators and the psychologists. Clearly, the graphologists fell far short of the nearly perfect accuracy they predicted they would demonstrate. In fact, in one case, the untrained assessors actually outperformed the graphologists—

Overall, the completely inexperienced judges achieved a success rate of 59 percent correct. The professional graphologists achieved a slightly better success rate of 65 percent. Obviously, this is not a great difference.

Hundreds of other studies have cast similar doubts on the ability of graphology to identify personality characteristics and to predict job performance from handwriting samples (Bangerter & others, 2009; Dazzi & Pedrabissi, 2009). In a global review of the evidence, psychologist Barry Beyerstein (1996) wrote, “Graphologists have unequivocally failed to demonstrate the validity or reliability of their art for predicting work performance, aptitudes, or personality. . . . If graphology cannot legitimately claim to be a scientific means of measuring human talents and leanings, what is it really? In short, it is a pseudoscience.”

How do graphologists respond to the scientific evidence? Many just ignore it. One search company executive pointed to the high satisfaction of his clients at the companies for which he uses graphology (Schofield, 2013). He said, “just because we cannot measure its success rate using mathematics or statistics—

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF PROJECTIVE TESTS

Although sometimes used in research, projective tests are mainly used in counseling and psychotherapy. According to many clinicians, the primary strength of projective tests is that they provide a wealth of qualitative information about an individual’s psychological functioning, information that can be explored further in psychotherapy.

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that projective tests, like the famous Rorschach inkblot test, accurately reveal personality traits and unconscious conflicts?

However, there are several drawbacks to projective tests. First, the testing situation or the examiner’s behavior can influence a person’s responses. Second, the scoring of projective tests is highly subjective, requiring the examiner to make numerous judgments about the person’s responses. Consequently, two examiners may test the same individual and arrive at different conclusions. Third, projective tests often fail to produce consistent results. If the same person takes a projective test on two separate occasions, very different results may be found. Finally, projective tests are poor at predicting future behavior.

The bottom line? Despite their widespread use, hundreds of studies of projective tests seriously question their validity—that the tests measure what they purport to measure—

Self-Report Inventories

DOES ANYONE HAVE AN ERASER?

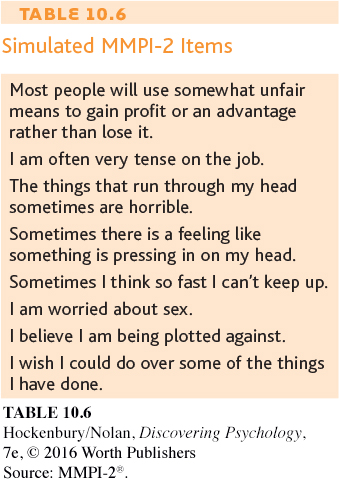

Self-

The most widely used self-

The MMPI is widely used by clinical psychologists and psychiatrists to assess patients. It is also used to evaluate the mental health of candidates for such occupations as police officers, doctors, nurses, and professional pilots. What keeps people from simply answering items in a way that makes them look psychologically healthy? Like many other self-

The MMPI was originally designed to assess mental health and detect psychological symptoms. In contrast, the California Psychological Inventory and the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire are personality inventories that were designed to assess normal populations (Boer & others, 2008; Megargee, 2009). Of the over 400 true–

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that there are ways to tell if you fake an answer on a personality test?

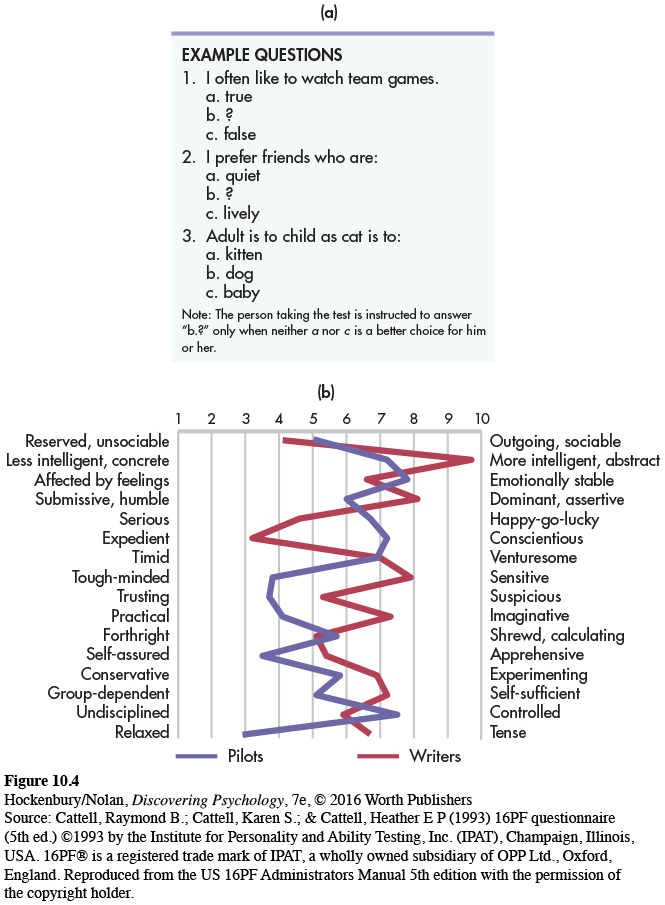

The Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF) was originally developed by Raymond Cattell and is based on his trait theory. The 16PF uses a forced-

Another widely used personality test is the Myers–

The notion of personality types is fundamentally different from personality traits. According to trait theory, people display traits, such as introversion/extraversion, to varying degrees. If you took the 16PF or the CPI, your score would place you somewhere along a continuum from low (very introverted) to high (very extraverted). However, most people would fall in the middle or average range on this trait dimension. But according to type theory, a person is either an extrovert or an introvert—

The MBTI arrives at personality type by measuring a person’s preferred way of dealing with information, making decisions, and interacting with others. There are four basic categories of these preferences, which are assumed to be dichotomies—that is, opposite pairs. These dichotomies are: Extraversion/Introversion; Sensing/Intuition; Thinking/Feeling; and Perceiving/Judging.

There are 16 possible combinations of scores on these four dichotomies. Each combination is considered to be a distinct personality type. An individual personality type is described by the initials that correspond to the person’s preferences as reflected in her MBTI score. For example, an ISFP combination would be a person who is introverted, sensing, feeling, and perceiving, while an ESTJ would be a person who is extroverted, sensing, thinking, and judging.

Think Like a SCIENTIST

Can an assessment of your personality predict job success? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Employment-

Despite the MBTI’s widespread use in business, counseling, and career guidance settings, research has pointed to several problems with the MBTI. One problem is reliability—people can receive different MBTI results on different test-

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF SELF-

The two most important strengths of self-

As a general rule, the reliability and validity of self-

Self-

However, self-

Third, people are not always accurate judges of their own behavior, attitudes, or attributes. And some people defensively deny their true feelings, needs, and attitudes, even to themselves (Cousineau & Shedler, 2006; Shedler & others, 1993). For example, a person might indicate that she enjoys parties, even though she actually avoids social gatherings whenever possible.

To sum up, personality tests are generally useful strategies that can provide insights about the psychological makeup of people. But no personality test, by itself, is likely to provide a definitive description of a given individual. In practice, psychologists and other mental health professionals usually combine personality test results with behavioral observations and background information, including interviews with family members, co-

Test your understanding of Assessing Personality with  .

.