Attribution

EXPLAINING BEHAVIOR

KEY THEME

Attribution refers to the process of explaining your own behavior and the behavior of other people.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the fundamental attribution error and the self-

serving bias? How do attributional biases affect our judgments about the causes of behavior?

How does culture affect attributional processes?

On the first day of class, you sit down and turn to say hi to the classmate next to you. She ignores you and focuses on her phone. You think to yourself, “What a jerk.”

Why did you arrive at that conclusion? After all, it’s completely possible that your classmate is having a very bad day and just doesn’t feel up to talking or is responding to an urgent text message.

Attribution is the process of inferring the cause of someone’s behavior, including your own. Psychologists also use the word attribution to refer to the explanation you make for a particular behavior. The attributions you make strongly influence your thoughts and feelings about other people.

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that you judge yourself more harshly than you judge other people when something goes wrong?

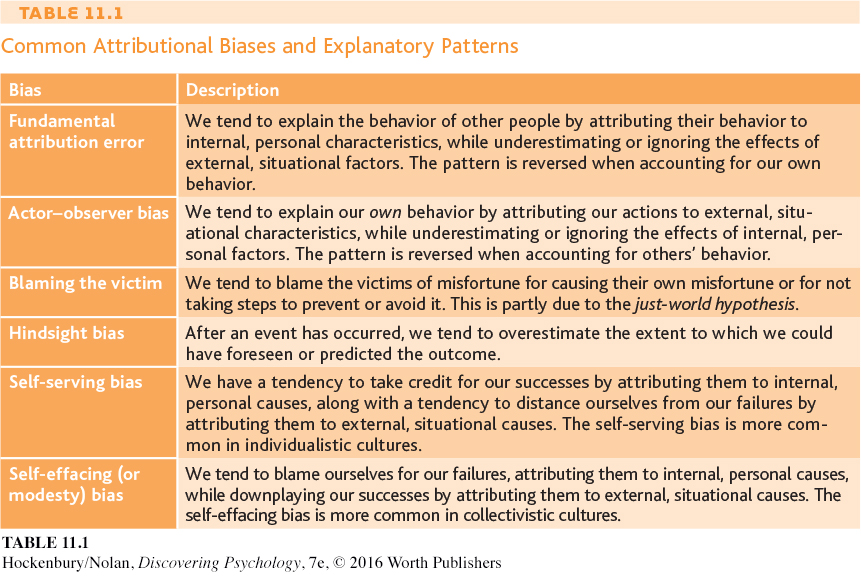

If your explanation for the silent classmate is that she is just an unpleasant, unfriendly person, you demonstrated a common cognitive bias. The fundamental attribution error is the tendency to spontaneously attribute the behavior of others to internal, personal characteristics, while ignoring or underestimating the role of external, situational factors (Ross, 1977). Even though it’s entirely possible that situational forces were behind another person’s behavior, we tend to automatically assume that the cause is an internal, personal characteristic (Bauman & Skitka, 2010; Zimbardo, 2007).

Notice, however, that when it comes to explaining our own behavior, we tend to be biased in the opposite direction, a tendency called the actor–

Why the discrepancy in accounting for the behavior of others as compared to our own behavior? Part of the explanation is that we simply have more information about the potential causes of our own behavior than we do about the causes of other people’s behavior. When you observe another driver turn directly into the path of your car, that’s typically the only information you have on which to judge his or her behavior. But when you inadvertently pull in front of another car, you perceive your own behavior in the context of the various situational factors, such as road conditions, that influenced your action. You also know what motivated your behavior and how differently you have behaved in similar situations in the past. Thus, you’re much more aware of the extent to which your behavior has been influenced by situational factors (Jones, 1990).

The fundamental attribution error plays a role in a common explanatory pattern called blaming the victim. The innocent victim of a crime, disaster, or serious illness is blamed for having somehow caused the misfortune or for not having taken steps to prevent it. For example, many people blame the poor for their dire straits, the sick for bringing on their illnesses, and victims of domestic violence or rape for somehow “provoking” their attackers.

The blaming the victim explanatory pattern is reinforced by another common cognitive bias. Hindsight bias is the tendency, after an event has occurred, to overestimate one’s ability to have foreseen or predicted the outcome (Roese & Vohs, 2012). In everyday conversations, this is the person who confidently proclaims after the event, “I could have told you that would happen.” In the case of blaming the victim, hindsight bias makes it seem as if the victim should have been able to predict—

Why do people often resort to blaming the victim? People have a strong need to believe that the world is fair—

The Self-Serving Bias

USING EXPLANATIONS TO MEET OUR NEEDS

If you’ve ever listened to other students react to their grades on an important exam, you’ve seen the self-

In a wide range of situations, people tend to credit themselves for their success and to blame their failures on external circumstances (Krusemark & others, 2008; Mezulis & others, 2004). Psychologists explain the self-

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

Explaining Failure and Murder: Culture and Attributional Biases

Although the self-

For example, compared to American students, Japanese and Chinese students are more likely to attribute academic failure to personal factors, such as lack of effort, instead of situational factors (Dornbusch & others, 1996). Thus, a Japanese student who does poorly on an exam is likely to say, “I didn’t study hard enough.” In contrast, Japanese and Chinese students tend to attribute academic success to situational factors. For example, they might say, “The exam was very easy” or “There was very little competition this year” (Stevenson & others, 1986).

One study asked participants to rate people who were answering questions about their achievements (Chen & Jing, 2012). Collectivistic participants tended to prefer the people who gave modest answers, whereas individualistic participants tended to like people who boasted in their answers.

Cross-

To test this idea in a naturally occurring context, psychologists Michael Morris and Kaiping Peng (1994) compared articles reporting the same mass murders in Chinese-

The American reporters were more likely to explain the killings by making personal, internal attributions. For example, American reporters emphasized the postal worker’s “history of being mentally unstable.” In contrast, the Chinese reporters emphasized situational factors, such as the fact that the postal worker had recently been fired from his job.

Clearly, then, how we account for our successes and failures, as well as how we account for the actions of others, is yet another example of how human behavior is influenced by cultural conditioning.

Haughtiness invites ruin; humility receives benefits.

—Chinese Proverb

Although common in many societies, the self-

Test your understanding of Person Perception and Attribution with  .

.