The Social Psychology of Attitudes

KEY THEME

An attitude is a learned tendency to evaluate objects, people, or issues in a particular way.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the three components of an attitude?

Under what conditions are attitudes most likely to determine behavior?

What is cognitive dissonance?

Should high school graduation requirements include a class on basic sex education, birth control methods, and safe sex? Should there be a compulsory military or community service requirement for all young adults? Should the government be doing more to prepare for climate change?

On these and many other subjects, you’ve probably formed an attitude. Psychologists formally define an attitude as a learned tendency to evaluate some object, person, or issue in a particular way (Banaji & Heiphetz, 2010; Bohner & Dickel, 2011). Attitudes are typically positive or negative, but they can also be ambivalent, as when you have mixed feelings about an issue, person, or group (Costarelli, 2011).

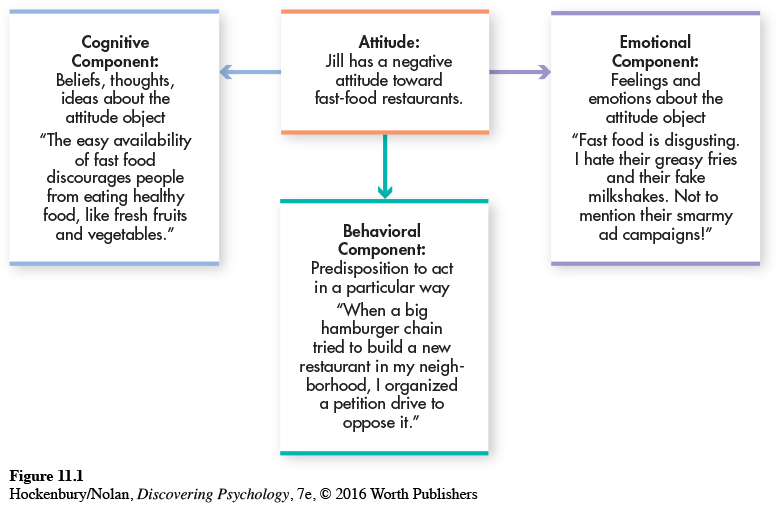

As shown in Figure 11.1 on the next page, attitudes can include three components. First, an attitude may have a cognitive component: your thoughts about a given topic or object. For example, Emil is an art lover. He often tells his friends that, in his opinion, visiting galleries and museums encourages people to be more open to new experiences. Second, an attitude may have an emotional or affective component, as when Emil talks excitedly about how energized he is after seeing an exhibition of Jeff Koons’ art. Finally, an attitude may have a behavioral component, in which attitudes are reflected in action, as when Emil donates to an organization that introduces schoolchildren to the arts.

Along with forming attitudes toward objects, ideas, or political campaigns, we also form attitudes about people. The In Focus box “Interpersonal Attraction and Liking” discusses some of the factors that affect the thoughts and feelings that we develop about other people.

The Effect of Attitudes on Behavior

Intuitively, you probably assume that your attitudes tend to guide your behavior. But social psychologists have consistently found that people don’t always act in accordance with their attitudes. For example, you might disapprove of cheating yet find yourself peeking at a classmate’s exam paper when the opportunity presents itself.

When are your attitudes likely to influence or determine your behavior? Social psychologists have found that you’re most likely to behave in accordance with your attitudes when:

You anticipate a favorable outcome or response from others for behaving that way.

Your attitudes are extreme or are frequently expressed (Ajzen, 2001).

You are very knowledgeable about the subject (Fabrigar & Wegener, 2010).

You have a vested interest in the subject and personally stand to gain or lose something on a specific issue (Thornton & Tizard, 2010).

Clearly, your attitudes do influence your behavior in many instances. Now, consider the opposite question: Can your behavior influence your attitudes?

The Effect of Behavior on Attitudes

FRIED GRASSHOPPERS FOR LUNCH?!

Suppose you have volunteered to participate in a psychology experiment. At the lab, a friendly experimenter asks you to indicate your degree of preference for a variety of foods, including fried grasshoppers, which you rank pretty low on the list. During the experiment, the experimenter instructs you to eat some fried grasshoppers. You manage to swallow three of the crispy critters. At the end of the experiment, your attitudes toward grasshoppers as a food source are surveyed again.

IN FOCUS

Interpersonal Attraction and Liking

In psychology, attraction refers to feeling drawn to other people—

What makes one person more attractive than another? Personal characteristics such as warmth and trustworthiness, adventurousness, and social status influence judgments of attractiveness (Finkel & Baumeister, 2010; Sprecher & Felmlee, 2008). But physical appearance, especially facial features, is probably the most significant factor in attraction. Studies reveal that wide smiles, high eyebrows, dilated pupils, and full lips are judged as attractive by both men and women, and that these preferences are consistent across many cultures (Chatterjee, 2011; Perrett, 2010). Some evolutionary psychologists argue that we associate attractive facial features with health, a desirable characteristic in a mating partner (Fink & Penton-

Some aspects of attraction are interpersonal. For example, we are more attracted to people whom we perceive as being like us—

Familiarity is another predictor of attraction and liking. In general, the more we interact with a person, the more we tend to like that person. Why? One explanation is that most interactions with other people are relatively pleasant (Reis & others, 2011). So, unless a person is particularly obnoxious or unpleasant, frequent interactions lead to more feelings of mutual pleasure, understanding, and acceptance.

The situations in which we interact with people also affect attraction. When happy, intoxicated, or physically aroused by exercise or exertion, we are more likely to rate others as attractive (Finkel & Baumeister, 2010). And, if we anticipate that attractive people are likely to be attracted to or like us, we’re more likely to be attracted to them, to like them, and to behave warmly toward them (Stinson & others, 2009).

Finally, feelings of attraction can be influenced by the socioeconomic and cultural environment. For example, cross-

But is it culture or hunger that shapes a preference for heavier women? In a clever study, Leif Nelson and Evan Morrison (2005) compared the preferences of college students as they were entering and leaving a campus dining hall at dinnertime. The presumably hungry men entering the dining hall preferred heavier women than the satiated men exiting the dining hall. (Having an empty or full stomach didn’t affect the female college students’ ratings of an ideal body shape.) The moral of the story: Culture affects body shape preference, but may do so through processes that are not culture-

Researchers have also observed a preference for specific body proportions that is consistent across cultures (Singh & others, 2010). Whether heavy or thin, a woman with a waist that is a good deal smaller than her hips seems to be universally viewed as attractive. This is true even among men who are blind; without ever having seen images of women considered beautiful, they preferred this proportion when they felt female mannequins (Karremans & others, 2010). Why? This body proportion has been shown to predict both lower risk for a range of diseases, including diabetes and cancer, and increased reproductive success (Singh & Singh, 2011). Evolutionary researchers suggest that this preference makes perfect sense, as a healthy reproductive partner increases the chance of genes being passed on. (The research on mate preferences is discussed further on page 378 in Chapter 9.)

Later in the day, you talk to a friend who also participated in the experiment. You mention how friendly and polite you thought the experimenter was. But your friend had a different experience. He thought the experimenter was an arrogant, rude jerk.

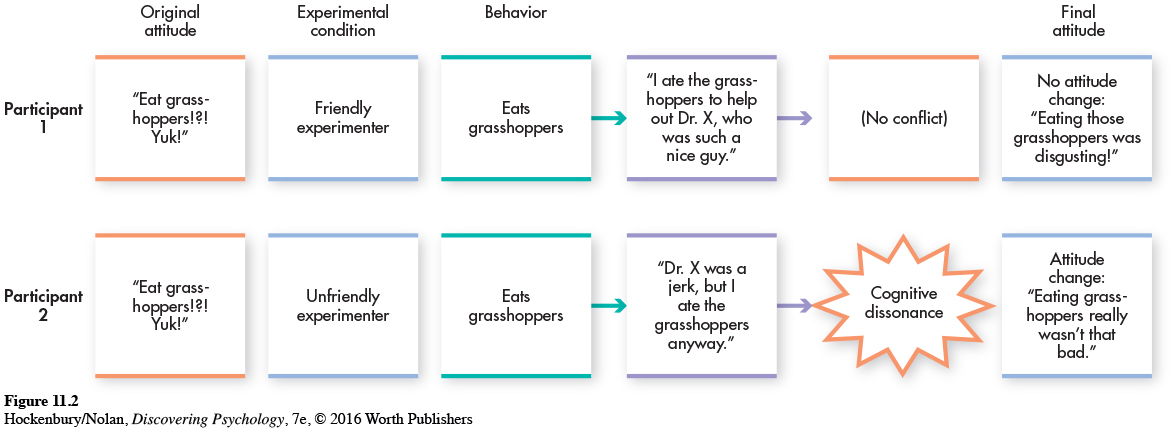

Here’s the critical question: Whose attitude toward eating fried grasshoppers is more likely to change in a positive direction? Given that you interacted with a friendly experimenter, most people assume that your feelings about fried grasshoppers are more likely to have improved than your friend’s attitude. In fact, it is your friend—

At first glance, this finding seems to go against the grain of common sense. So how can we explain this outcome? The fried grasshoppers story represents the basic design of a classic experiment by social psychologist Philip Zimbardo and his colleagues (1965). Zimbardo’s experiment underscored the importance of cognitive dissonance, a phenomenon first identified by social psychologists Leon Festinger and J. Merrill Carlsmith (1959). Cognitive dissonance is an unpleasant state of psychological tension (dissonance) that occurs when there’s an inconsistency between two thoughts or perceptions (cognitions). This state of dissonance is so unpleasant that we are strongly motivated to reduce it (Festinger, 1957, 1962; Gawronski, 2012).

Cognitive dissonance commonly occurs in situations in which you become uncomfortably aware that your behavior and your attitudes are in conflict (Cooper, 2012). In these situations, you are simultaneously holding two conflicting cognitions: your original attitude versus the realization that your behavior contradicts that attitude. If you can easily rationalize your behavior to make it consistent with your attitude, then any dissonance you might experience can be quickly and easily resolved. But when your behavior cannot be easily justified, how can you resolve the contradiction and eliminate the unpleasant state of dissonance? Since you can’t go back and change the behavior, you change your attitude to make it consistent with your behavior.

Zimbardo’s research has ranged from attitude change to shyness, prison reform, and the psychology of evil. As Zimbardo (2000b) observes, “The joy of being a psychologist is that almost everything in life is psychology, or should be, or could be.” Later in the chapter, we’ll encounter Zimbardo’s most famous—

Let’s take another look at the results of the grasshopper study, this time from the perspective of cognitive dissonance theory. Your attitude toward eating grasshoppers did not change. Why? Because you could easily rationalize the conflict between your attitude (“Eating grasshoppers is disgusting”) and your behavior (eating three grass-

Research from social neuroscience suggests that cognitive dissonance can lead to attitude change quickly, perhaps without us even realizing that the process is occurring. Difficult decisions are often followed by an attitude change that favors the object or outcome chosen. Brain scans show changes in the parts of the brain associated with distress, arousal, emotion, and conflict within seconds after a person makes a difficult decision, which may indicate the discomfort produced by the change in attitude (Jarcho & others, 2010; van Veen & others, 2009).

This response to cognitive dissonance does not seem to be unique to adults or even humans. Louisa Egan and her colleagues (2007) have seen dissonance among four-

Attitude change due to cognitive dissonance is quite common in everyday life. For example, consider the person who impulsively buys a new leather coat that she really can’t afford. “It was too good a bargain to pass up,” she rationalizes. Similarly, researchers have found that people who quit smoking offered fewer rationalizations for smoking. But if they started smoking again, they started rationalizing again. For example, some said, “You’ve got to die of something, so why not enjoy yourself and smoke” (Fotuhi & others, 2013).

Cognitive dissonance also influences how we frame decisions we have made when we have chosen between two alternatives, such as which college to attend. After you make a choice, you emphasize the negative features of the choice you’ve rejected, which is commonly called a “sour grapes” rationalization. You also emphasize the positive features of the choice to which you have committed yourself—