Understanding Prejudice

KEY THEME

Prejudice refers to a negative attitude toward people who belong to a specific social group, while stereotypes are clusters of characteristics that are attributed to people who belong to specific social categories.

KEY QUESTIONS

What is the function of stereotypes, and how do they relate to prejudice?

What are in-

groups and out- groups, and how do they influence social judgments? What are implicit attitudes, and how are they measured?

In this section, you’ll see how person perception, attribution, and attitudes come together in explaining prejudice—a negative attitude toward people who belong to a specific social group.

Prejudice is ultimately based on the exaggerated notion that members of other social groups are very different from members of our own social group. So as you read this discussion, it’s important for you to keep two well-

It also is important to observe that conversations about prejudice often focus on race and ethnicity. But prejudice can occur with respect to many different kinds of social groups. There can be prejudice based on sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, or age. There can also be prejudice based on a person’s identification with multiple groups (Herek & McLemore, 2013; Kang & Bodenhausen, 2015; Newheiser & others, 2013; North & Fiske, 2013). For example, one study found that older people were perceived more negatively than middle-

From Stereotypes to Prejudice

IN-

As we noted earlier, using social categories to organize information about other people seems to be a natural cognitive tendency. Many social categories can be defined by relatively objective characteristics, such as age, language, religion, and skin color. A specific kind of social category is a stereotype—a cluster of characteristics that are attributed to members of a specific social group or category. Stereotypes are based on the assumption that people have certain characteristics because of their membership in a particular group.

Stereotypes typically include qualities that are unrelated to the objective criteria that define a given category (Crawford & others, 2011). For example, we can objectively sort people into different categories by age. But our stereotypes for different age groups may include qualities that have little or nothing to do with “number of years since birth.” Associations of “impulsive and irresponsible” with teenagers, or “boring and conservative” with middle-

Like our use of other social categories, our tendency to stereotype social groups seems to be a natural cognitive process. Stereotypes simplify social information so that we can sort out, process, and remember information about other people more easily (Bodenhausen & Richeson, 2010). But like other mental shortcuts we’ve discussed in this chapter, relying on stereotypes can cause problems. Attributing a stereotypic cause for an outcome or event can blind us to the true causes of events (Johnston & Miles, 2007). For example, a parent who assumes that a girl’s poor computer skills are due to her gender rather than a lack of instruction might never encourage her to overcome her problem.

Research by psychologist Claude Steele (1997, 2003, 2011) has demonstrated another detrimental effect of negative stereotypes, which he calls stereotype threat. As we discussed in Chapter 7, simply being aware that your social group is associated with a particular stereotype can negatively impact your performance on tests or tasks that measure abilities that are thought to be associated with that stereotype (Schmader, 2010; Shapiro & others, 2013). For example, even mathematically gifted women tend to score lower on difficult math tests when told that the test tended to produce gender differences than when told that such tests did not produce gender differences (Forbes & Schmader, 2010; Rydell & others, 2010). (On pages 304–305 in Chapter 7, you’ll find some suggestions for counteracting the effects of stereotype threat.)

Once they are formed, stereotypes are hard to shake. Sometimes stereotypes have a kernel of truth, making them easy to confirm, especially when you see only what you expect to see. Even so, there’s a vast difference between a kernel and the cornfield. When stereotypic beliefs become expectations that are applied to all members of a given group, stereotypes can be both misleading and damaging (Dovidio & Gaertner, 2010).

Consider the stereotype that men are more assertive than women and that women are more nurturing than men. This stereotype does have evidence to support it, but only in terms of the average difference between men and women (Wood & Eagly, 2010). Thus, it would be unfair and often inaccurate to automatically apply this stereotype to every individual man and woman.

Equally important, when confronted by evidence that contradicts a stereotype, people tend to discount that information in a variety of ways (Phelan & Rudman, 2010; Rudman & Fairchild, 2004). For example, suppose you are firmly convinced that all “Zeegs” are dishonest, sly, and untrustworthy. One day you absent-

Will this experience change your stereotype of Zeegs as dishonest, sly, and untrustworthy? Probably not. It’s more likely that you’ll conclude that this individual Zeeg is an exception to the stereotype. If you run into more than one honest Zeeg, you may create a mental subgroup for individuals who belong to the larger group but depart from the stereotype in some way (Queller & Mason, 2008; Sherman & others, 2005). By creating a subcategory of “honest, hardworking Zeegs,” you can still maintain your more general stereotype of Zeegs as dishonest, sly, and untrustworthy.

Creating exceptions allows people to maintain stereotypes in the face of contradictory evidence. Typical of this exception-

Stereotypes are closely related to another tendency in person perception. People have a strong tendency to perceive others in terms of two very basic social categories: “us” and “them.” More precisely, the in-

In-

THE OUT-

THEY’RE ALL THE SAME TO ME

Two important patterns characterize our views of in-

Second, we tend to see members of the out-

For example, what qualities do you associate with the category of “engineering major”? If you’re not an engineering major, you’re likely to see engineering majors as a rather similar crew: male, logical, analytical, conservative, and so forth. However, if you are an engineering major, you’re much more likely to see your in-

IN-

WE’RE TACTFUL—

In-

In combination, stereotypes and in-

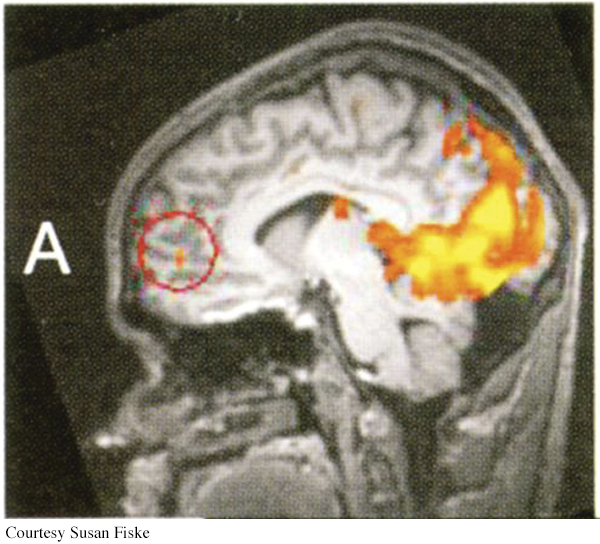

How can we account for the extreme emotions that often characterize prejudice against out-

But prejudice often exists in the absence of direct competition for resources, changing social conditions, or even contact with members of a particular out-

IMPLICIT ATTITUDES

Most people today agree that prejudice and racism are wrong. Blatant displays of racist, sexist, or homophobic speech or behavior are no longer socially acceptable. However, some psychologists now believe that overt forms of prejudice have been replaced by more subtle forms of prejudice (Hewstone & others, 2002; Sritharan & Gawronski, 2010).

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that if you believe you are not prejudiced, you will not behave in prejudiced ways?

Sometimes people who are not consciously prejudiced against particular groups nevertheless respond in prejudiced ways (Plant & Devine, 2009). For example, a man who consciously strives to be nonsexist may be reluctant to consult a female surgeon, or when he hears a news story that mentions a police officer, he may assume the officer is a man. Such biased responses can sometimes affect behavior in ways that we neither intend nor realize (Devine, 2001; Stanley & others, 2011). And many of these effects can be harmful. For black Americans, for example, implicit attitudes about race have been linked to difficulties getting hired or receiving lifesaving medical treatment, to higher rates of discipline in school, and to an increased likelihood of being the victim of police violence (Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015; Richardson, 2015).

How can such responses be explained? In contrast to explicit attitudes, of which you are consciously aware, implicit attitudes are evaluations that are automatic, unintentional, and difficult to control (Bohner & Dickel, 2011). They are sometimes, but not always, unconscious (Sritharan & Gawronski, 2010).

Our implicit attitudes often differ from our explicit attitudes, especially when social and cultural norms prohibit negative attitudes regarding race, gender, or sexual orientation (Bodenhausen & Richeson, 2010). If people won’t admit or aren’t consciously aware of implicit attitudes, how can they be detected and measured? The most widely used test to measure implicit attitudes and preferences is the Implicit Association Test, or IAT, developed by psychologist Anthony Greenwald and his colleagues (1998).

The IAT is a computer-

What factors affect whether you see this behavior as violent? Try Lab: Stereotyping.

Other IATs measure implicit attitudes toward sexual orientation, weight, disability, and racial and ethnic groups. IATs have also been developed to measure the strength of stereotyped associations, such as the strength of associations between gender and career or family. You can try the IAT yourself online at: https://implicit.harvard.edu.

The IAT has been completed by over 10 million people around the world (Banaji & Heiphetz, 2010). The results suggest that implicit preferences are quite pervasive. As Brian Nosek and his colleagues (2007) concluded, “With few exceptions, across domains and demographic categories, participants showed implicit and explicit social preferences and stereotypes. Men and women, young and old, conservative and liberal, Black, White, Asian, and Hispanic—

Although in wide use, the IAT is controversial (see Amodio & Mendoza, 2010; Azar, 2008). For example, some researchers argue that the ease with which certain associations are made may reflect familiarity with cultural stereotypes, rather than personal bias or prejudice (Blanton & others, 2009). Other researchers have demonstrated that brief training can reduce prejudice as measured by the IAT (Calanchini & others, 2013). And, the degree to which implicit attitudes affect actual behavior is still an open question, although some studies suggest that they do (see Greenwald & others, 2009; Stanley & others, 2011).

Despite controversies about the IAT, there is evidence that implicit attitudes can be changed. For example, psychologists agree that becoming aware of our biased attitudes, whether implicit or explicit, is an important step toward overcoming them (Devine & others, 2012; Paluck & Green, 2009). Also, mindfulness meditation, introduced in the chapter on consciousness, has been shown to reduce implicit bias based on both age and race (Lueke & Gibson, 2015). We turn to the topic of overcoming prejudice in the next section.

Overcoming Prejudice

KEY THEME

Prejudice can be overcome when people cooperate to achieve a common goal.

KEY QUESTIONS

How has this finding been applied in the educational system?

What other conditions are essential to reducing tension between groups?

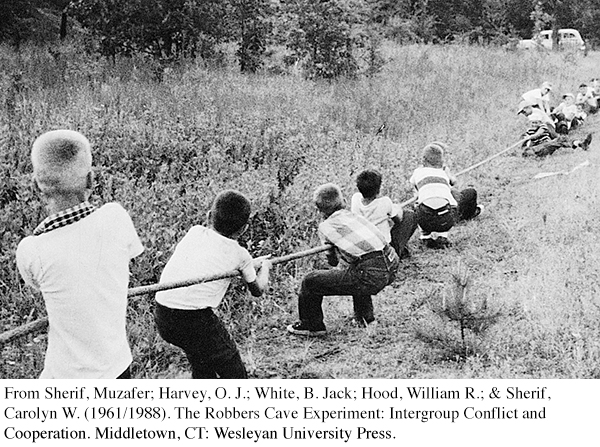

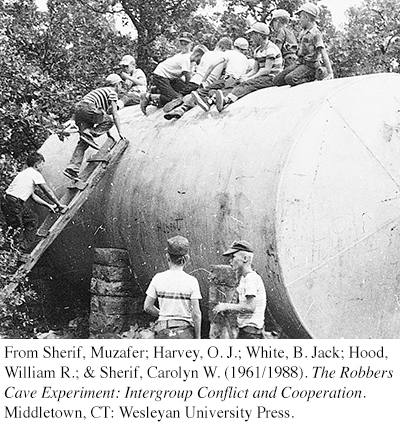

How can prejudice be combated? A classic series of studies headed by psychologist Muzafer Sherif helped clarify the conditions that produce intergroup conflict and harmony. Sherif and his colleagues (1961) studied a group of 11-

THE ROBBERS CAVE EXPERIMENT

Pretending to be camp counselors and staff, the researchers observed the boys’ behavior under carefully orchestrated conditions. The boys were randomly assigned to two groups. The groups arrived at camp in separate buses and were headquartered in different areas of the camp. One group of boys dubbed themselves the Eagles, the other the Rattlers. After a week of separation, the researchers arranged for the groups to meet in a series of competitive games. A fierce rivalry quickly developed, demonstrating the ease with which mutually hostile groups could be created.

The rivalry became increasingly bitter. The Eagles burned the Rattlers’ flag. In response, the Rattlers trashed the Eagles’ cabin. Somewhat alarmed, the researchers tried to diminish the hostility by bringing the two groups together under peaceful circumstances and on an equal basis—

How could harmony between the groups be established? Sherif and his fellow researchers created a series of situations in which the two groups would need to cooperate to achieve a common goal. For example, the researchers secretly sabotaged the water supply. Working together, the Eagles and the Rattlers managed to fix it. After a series of such joint efforts, the rivalry diminished and the groups became good friends (Sherif, 1956; Sherif & others, 1961).

Sherif successfully demonstrated how hostility between groups could be created and, more important, how that hostility could be overcome. However, other researchers questioned whether these results would apply to other intergroup situations. After all, these boys were very homogeneous: white, middle class, Protestant, and carefully selected for being healthy and well-

THE JIGSAW CLASSROOM

PROMOTING COOPERATION

Social psychologist Elliot Aronson (1990, 1992) tried adapting the results of the Robbers Cave experiments to a very different group situation—

Aronson and his colleagues tried a teaching technique that stressed cooperative, rather than competitive, learning situations (see Aronson, 1990; Aronson & Bridgeman, 1979). Dubbed the jigsaw classroom technique, this approach brought together students in small, ethnically diverse groups to work on a mutual project. Like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, each student became an expert on one aspect of the overall project and had to teach it to the other members of the group. Thus, interdependence and cooperation replaced competition.

The results? Children in the jigsaw classrooms had higher self-

Lessons from Robbers Cave and the jigsaw classroom have been used to reduce prejudice and conflict among ethnic and religious groups around the world (Aboud & others, 2012). For example, a number of programs have been developed to promote cooperation between Israelis and Palestinians through joint projects in which members of both groups work together to stage a play, conduct scientific studies, or play on a soccer team (Maoz, 2012).

Test your understanding of The Psychology of Attitudes and Prejudice with  .

.