Conformity

FOLLOWING THE CROWD

KEY THEME

Social influence involves the study of how behavior is influenced by other people and by the social environment.

KEY QUESTIONS

What factors influence the degree to which people will conform?

Why do people conform?

How does culture affect conformity?

As we noted earlier, social influence is the psychological study of how our behavior is influenced by the social environment and other people. For example, if you typically contribute to class discussions, you’ve probably felt the power of social influence in classes where nobody else said a word (Stowell & others, 2010). No doubt you found yourself feeling at least slightly uncomfortable every time you ventured a comment.

Life in society requires consensus as an indispensable condition. But consensus, to be productive, requires that each individual contribute independently out of his experience and insight. When consensus comes under the dominance of conformity, the social process is polluted and the individual at the same time surrenders the powers on which his functioning as a feeling and thinking being depends.

—Solomon Asch (1955)

If you changed your behavior to mesh with that of your classmates, you demonstrated conformity. Conformity occurs when you adjust your opinions, judgment, or behavior so that it matches that of other people, or the norms of a social group or situation (Hogg, 2010).

There’s no question that all of us conform to group or situational norms to some degree. The more critical issue is how far we’ll go to adjust our perceptions and opinions so that they’re in sync with the majority opinion—

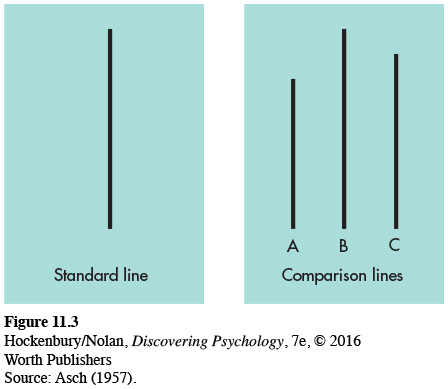

To study this question experimentally, Asch (1955) chose a simple, objective task with an obvious answer (Figure 11.3). A group of people sat at a table and looked at a series of cards. On one side of each card was a standard line. On the other side were three comparison lines. All each person had to do was publicly indicate which comparison line was the same length as the standard line.

Asch’s experiment had a hidden catch. All the people sitting around the table were actually in cahoots with the experimenter, except for one—

Then the third card is shown, and the correct answer is just as obvious: Line C. But the first person confidently says, “Line A.” And so does everyone else, one by one. Now it’s your turn. To you it’s clear that the correct answer is Line C. But the five people ahead of you have already publicly chosen Line A. How do you respond? You hesitate. Do you go with the flow or with what you know?

The real participant was faced with the uncomfortable situation of disagreeing with a unanimous majority on 12 of 18 trials in Asch’s experiment. Notice, there was no direct pressure to conform—

Over 100 participants experienced Asch’s experimental dilemma. Not surprisingly, participants differed in their degree of conformity. Nonetheless, the majority of Asch’s participants (76 percent) conformed with the group judgment on at least one of the critical trials. When the data for all participants were combined, the participants followed the majority and gave the wrong answer on 37 percent of the critical trials (Asch, 1955, 1957). In comparison, a control group of participants who responded alone instead of in a group accurately chose the matching line 99 percent of the time.

Although the majority opinion clearly exerted a strong influence, it’s also important to stress the flip side of Asch’s results. On almost two-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that if you’re sure of your answer, you’ll almost always stick to it even if others disagree with you?

Even those who conform may not have experienced a lasting change in their perception or opinion. One study observed conformity with respect to people’s opinions about others’ attractiveness (Huang & others, 2014). In follow-

Factors Influencing Conformity

The basic model of Asch’s classic experiment has been used in hundreds of studies exploring the dynamics of conformity (Bond, 2005). It’s even been examined in online contexts, where people are making decisions based on the responses of anonymous, unseen others (Rosander & Eriksson, 2012; Zhu & others, 2012). Why do we sometimes find ourselves conforming to the larger group? There are two basic reasons.

First is our desire to be liked and accepted by the group, which is referred to as normative social influence. Interestingly, the power of social influence may apply uniquely to humans. One study found that two-

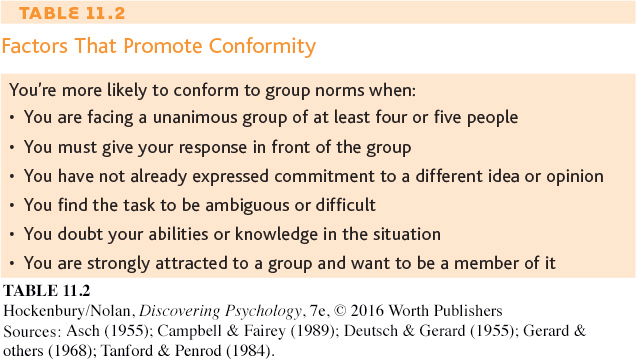

Asch and other researchers identified several conditions that promote conformity, which are summarized in Table 11.2. But Asch also discovered that conformity decreased under certain circumstances. For example, having an ally seemed to counteract the social influence of the majority. Participants were more likely to go against the majority view if just one other participant did so, even if the other person’s dissenting opinion is wrong (Allen & Levine, 1969; Packer, 2008b). Conformity also lessens even if the other dissenter’s competence is questionable, as in the case of a dissenter who wore thick glasses and complained that he could not see the lines very well (Allen & Levine, 1971; Turner, 2010).

Culture and Conformity

Do patterns of conformity differ in other cultures? The answer seems to be yes. A survey of more than 80,000 people from 62 countries found that the value placed on conformity varied widely across cultures (Fischer & Schwartz, 2011). How might conformity vary across cultures? British psychologists Rod Bond and Peter Smith (1996) found in a wide-

In collectivistic cultures, however, publicly conforming while privately disagreeing tends to be regarded as socially appropriate tact or sensitivity. Publicly challenging the judgments of others, particularly the judgment of members of one’s in-