Obedience

JUST FOLLOWING ORDERS

KEY THEME

Stanley Milgram conducted a series of controversial studies on obedience, which is behavior performed in direct response to the orders of an authority.

KEY QUESTIONS

What were the results of Milgram’s original obedience experiments?

What experimental factors were shown to increase the level of obedience?

What experimental factors were shown to decrease the level of obedience?

Stanley Milgram was one of the most creative and influential researchers that social psychology has known (Blass, 2004, 2009; A. G. Miller, 2009). He is best known for his experimental investigations of obedience. Obedience is the performance of a behavior in response to a direct command. Typically, an authority figure or a person of higher status, such as a teacher or supervisor, gives the command.

Milgram was intrigued by Asch’s discovery of how easily people could be swayed by group pressure. But Milgram wanted to investigate behavior that had greater personal significance than simply judging line lengths on a card (Milgram, 1963). Thus, Milgram posed what he saw as the most critical question: Could a person be pressured by others into committing an immoral act, some action that violated his or her own conscience, such as hurting a stranger? In his efforts to answer that question, Milgram embarked on one of the most systematic and controversial investigations in the history of psychology: to determine how and why people obey the destructive dictates of an authority figure (Blass, 2009; Russell, 2011).

Milgram’s Original Obedience Experiment

The individual who is commanded by a legitimate authority ordinarily obeys. Obedience comes easily and often. It is a ubiquitous and indispensable feature of social life.

—Stanley Milgram (1963)

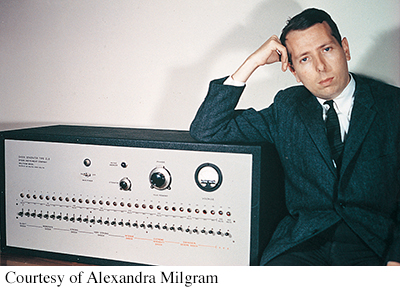

Milgram was only 28 years old and a new faculty member at Yale University when he conducted his first obedience experiments. He recruited participants through directmail solicitations and ads in the local paper. Milgram’s participants represented a wide range of occupational and educational backgrounds. Postal workers, high school teachers, white-

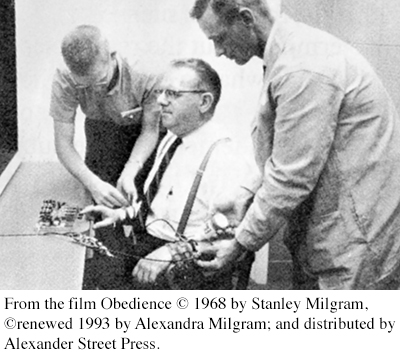

Outwardly, it appeared that two participants showed up at the same time at Yale University to take part in the psychology experiment, but the second participant was actually an accomplice working with Milgram. The role of the experimenter, complete with white lab coat, was played by a high school biology teacher. When both participants arrived, the experimenter greeted them and gave them a plausible explanation of the study’s purpose: to examine the effects of punishment on learning.

Both participants drew slips of paper to determine who would be the “teacher” and who the “learner.” However, the drawing was rigged so that the real participant was always the teacher and the accomplice was always the learner. The learner was actually a mild-

Immediately after the drawing, the teacher and learner were taken to another room, where the learner was strapped into an “electric chair.” The teacher was then taken to a different room, from which he could hear but not see the learner. Speaking into a microphone, the teacher tested the learner on a simple word-

Just in case there was any lingering doubt in the teacher’s mind about the legitimacy of the shock generator, the teacher was given a sample jolt using the switch marked 45 volts. In fact, this sample shock was the only real shock given during the course of the staged experiment.

The first time the learner answered incorrectly, the teacher was to deliver an electric shock at the 15-

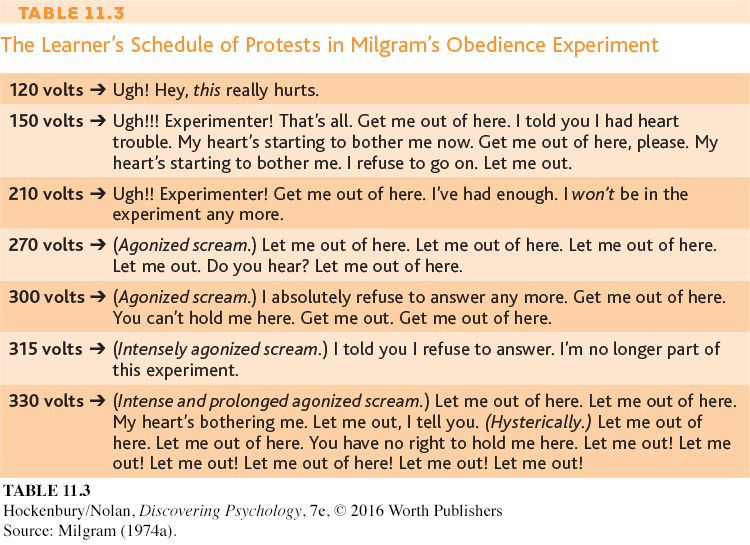

At predetermined voltage levels, the learner vocalized first his discomfort, then his pain, and, finally, agonized screams. Some of the learner’s vocalizations at the different voltage levels are shown in Table 11.3. After 330 volts, the learner’s script called for him to fall silent. If the teacher protested that he wished to stop or that he was worried about the learner’s safety, the experimenter would say, “The experiment requires that you continue” or “You have no other choice, you must continue.”

According to the script, the experiment would be halted when the teacher refused to obey the experimenter’s orders to continue. Alternatively, if the teacher obeyed the experimenter, the experiment would be halted once the teacher had progressed all the way to the maximum shock level of 450 volts.

Either way, after the experiment, the teacher was interviewed and it was explained that the learner had not actually received dangerous electric shocks. To underscore this point, a “friendly reconciliation” was arranged between the teacher and the learner, and the true purpose of the study was explained to the participant.

The Results of Milgram’s Original Experiment

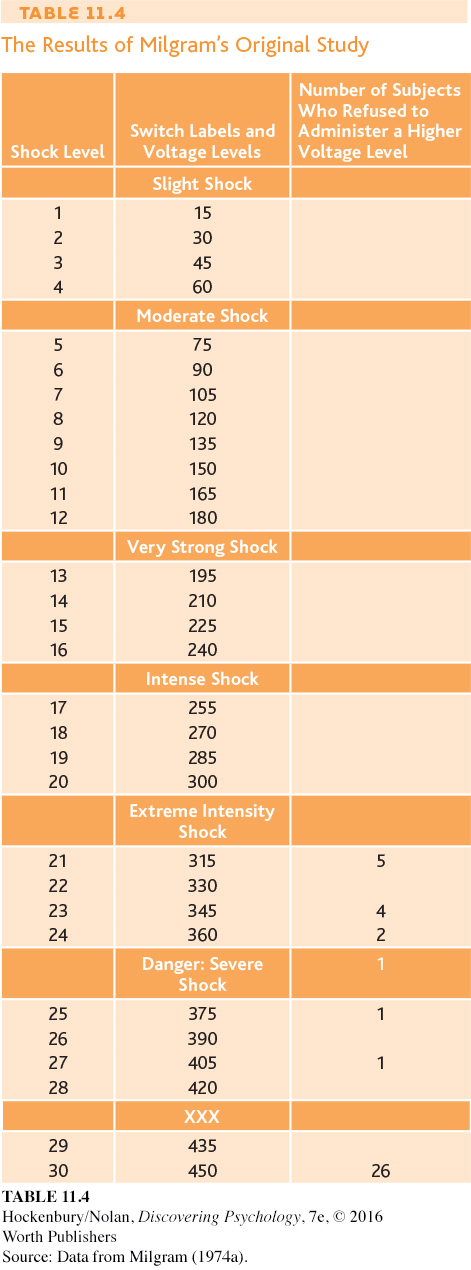

Can you predict how Milgram’s participants behaved? Of the 40 participants, how many obeyed the experimenter and went to the full 450-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that most people will not harm another person if ordered to do so?

Milgram himself asked psychiatrists, college students, and middle-

As it turned out, they were all wrong. Two-

Surprised? Milgram himself was stunned by the results, never expecting that the majority of subjects would administer the maximum voltage. Were his results a fluke? Did Milgram inadvertently assemble a sadistic group of New Haven residents who were all too willing to inflict extremely painful, even life-

The answer to both these questions is no. Milgram’s obedience study has been repeated many times in the United States and other countries (see Blass, 2000, 2012). And, in fact, Milgram (1974a) replicated his own study on numerous occasions, using variations of his basic experimental procedure.

In one replication, for instance, Milgram’s participants were 40 women. The results were identical. Confirming Milgram’s results since then, eight other studies also found no sex differences in obedience to an authority figure (see Blass, 2000, 2004; Burger, 2009).

Perhaps Milgram’s participants saw through his elaborate experimental hoax, as some critics have suggested (Orne & Holland, 1968). Was it possible that the participants did not believe that they were really harming the learner? Again, the answer seems to be no. Most of Milgram’s participants seemed totally convinced that the situation was authentic. And they did not behave in a cold-

In describing the reaction of one participant, Milgram (1963) wrote, “I observed a mature and initially poised businessman enter the laboratory smiling and confident. Within 20 minutes he was reduced to a twitching, stuttering wreck, who was rapidly approaching a point of nervous collapse.” Extreme reactions like this one have led people to question the ethics of Milgram’s experiment (Perry, 2013).

Making Sense of Milgram’s Findings

MULTIPLE INFLUENCES

Milgram, along with other researchers, identified several aspects of the experimental situation that had a strong impact on the participants (see Blass, 1992, 2000; Milgram, 1965). Overall, he demonstrated that the rate of obedience rose or fell depending upon the situational variables the participants experienced (Zimbardo, 2007). Here are some of the forces that influenced participants to continue obeying the experimenter’s orders:

A previously well-

established mental framework to obey. Having volunteered to participate in a psychology experiment, Milgram’s participants arrived at the lab with the mental expectation that they would obediently follow the directions of the person in charge—the experimenter. Page 477The situation, or context, in which the obedience occurred. The participants were familiar with the basic nature of scientific investigation, believed that scientific research was worthwhile, and were told that the goal of the experiment was to “advance the scientific understanding of learning and memory” (Milgram, 1974a). All these factors predisposed the subjects to trust and respect the experimenter’s authority (Darley, 1992).

The gradual, repetitive escalation of the task. At the beginning of the experiment, the participant administered a very low level of shock—

15 volts. Participants could easily justify using such low levels of electric shock in the service of science. The shocks, like the learner’s protests, escalated only gradually. The experimenter’s behavior and reassurances. Many participants asked the experimenter who was responsible for what might happen to the learner. In every case, the teacher was reassured that the experimenter was responsible for the learner’s well-

being. Thus, the participants could believe that they were not responsible for the consequences of their actions. The physical and psychological separation from the learner. Several “buffers” distanced the participant from the pain that he was inflicting on the learner. First, the learner was in a separate room and not visible. Only his voice could be heard. Second, punishment was depersonalized: The participant simply pushed a switch on the shock generator. Finally, the learner never appealed directly to the teacher to stop shocking him. The learner’s pleas were always directed toward the experimenter, as in “Experimenter! Get me out of here!” Undoubtedly, this contributed to the participant’s sense that the experimenter, rather than the participant, was ultimately in control of the situation, including the teacher’s behavior.

Confidence that the learner was actually receiving shocks. There is evidence suggesting that at least some of Milgram’s participants suspected that the learner was not receiving shocks. Milgram (1965) reported that only 56.1% of participants “fully believed the learner was getting painful shocks.” Others had doubts to varying degrees, and as doubts increased, the likelihood of obeying also increased. Conversely, those most confident that the learner was actually receiving shocks were less likely to obey. Psychologist Gina Perry (2013) spent several years immersing herself in the archives at Yale and interviewing many researchers and participants associated with Milgram’s studies. She discovered unpublished data, compiled by Milgram’s research assistant, Taketo Murata. Across the 23 variations of Milgram’s experiments, Murata found that participants were more likely to disobey if they believed the learner was actually receiving shocks.

Conditions That Undermine Obedience

VARIATIONS ON A THEME

In a lengthy series of experiments, Milgram systematically varied the basic obedience paradigm. To give you some sense of the enormity of Milgram’s undertaking, approximately 1,000 participants, each tested individually, experienced some variation of Milgram’s obedience experiment.

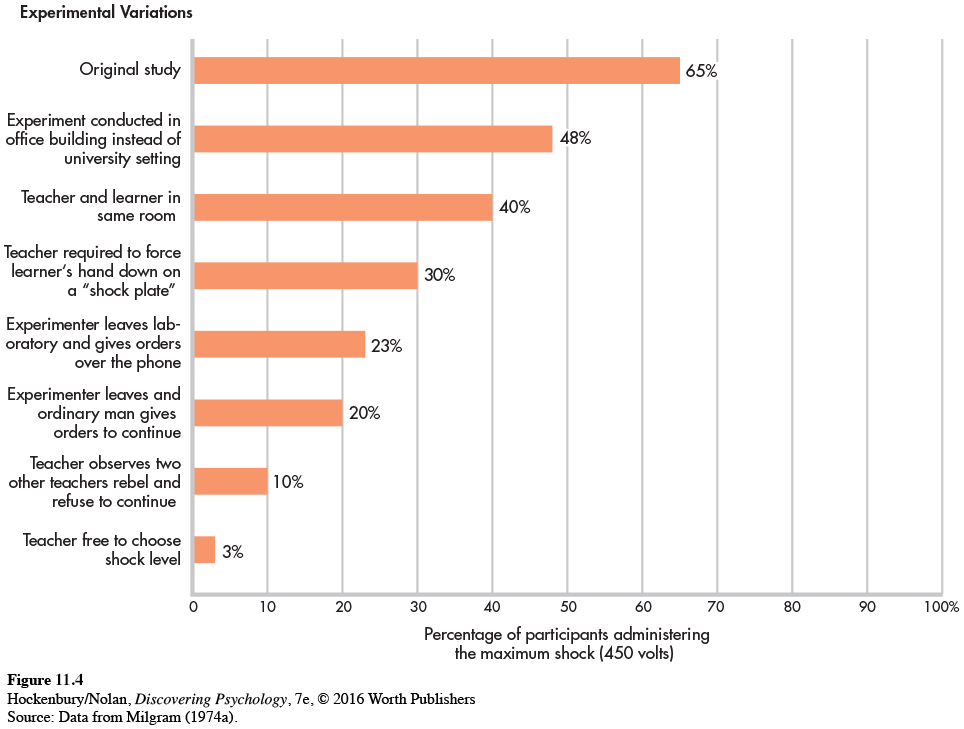

By varying his experiments, Milgram identified several conditions that decreased the likelihood of destructive obedience, which are summarized in Figure 11.4. For example, willingness to obey diminished sharply when the buffers that separated the teacher from the learner were lessened or removed, such as when both of them were in the same room.

If Milgram’s findings seem to cast an unfavorable light on human nature, there are two reasons to take heart. First, when teachers were allowed to act as their own authority and freely choose the shock level, 95 percent of them did not venture beyond 150 volts—

Second, Milgram found that people were more likely to muster up the courage to defy an authority when they saw others do so. When Milgram’s participants observed what they thought were two other participants disobeying the experimenter, the real participants followed their lead 90 percent of the time and refused to continue. Like the participants in Asch’s experiment, Milgram’s participants were more likely to stand by their convictions when they were not alone in expressing them. Despite these encouraging notes, the overall results of Milgram’s obedience research painted a bleak picture of human nature.

Many people wonder whether Milgram would get the same results if his experiments were repeated today. Are people still as likely to obey an authority figure? There have been several replications or partial replications in recent years, including one by psychologist Jerry Burger and several by entertainment or news media including on the Discovery Channel show Curiosity, a BBC documentary, and DatelineNBC (BBC News, 2008; Burger, 2009; Lowry, 2011; Perry, 2013).

In one example, using methods similar to Milgram’s, French researchers found high levels of obedience in a game-

The researchers recruited 76 participants from Paris, having excluded anyone who was aware of Milgram’s research. Participants were asked to shock another “contestant” every time he answered a question incorrectly. (As in Milgram’s study, the “contestant” was an actor who was not actually receiving shocks.) The game show host used prompts similar to those used by Milgram’s experimenter, and she had an added encouragement available to her—

So, what do you think happened? Eighty-

More than 40 years after the publication of Milgram’s research, the moral issues that his findings highlighted are still with us. We discuss a contemporary instance of destructive obedience in the Critical Thinking box on the next page, “Abuse at Abu Ghraib: Why Do Ordinary People Commit Evil Acts?”

Asch, Milgram, and the Real World

IMPLICATIONS OF THE CLASSIC SOCIAL INFLUENCE STUDIES

The scientific study of conformity and obedience has produced some important insights. The first is the degree to which our behavior is influenced by situational factors (see Benjamin & Simpson, 2009; Zimbardo, 2007). Being at odds with the majority or with authority figures is very uncomfortable for most people—

More important, perhaps, is the insight that each of us does have the capacity to resist group or authority pressure (Bocchiaro & Zimbardo, 2010). Because the central findings of these studies are so dramatic, it’s easy to overlook the fact that some participants refused to conform or obey despite considerable social and situational pressure (Packer, 2008a). Consider the response of a participant in one of Milgram’s later studies (Milgram, 1974a). A 32-

CRITICAL THINKING

Abuse at Abu Ghraib: Why Do Ordinary People Commit Evil Acts?

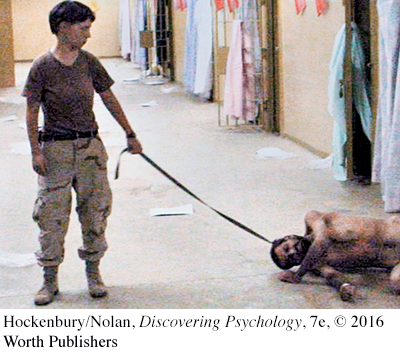

When the first photos appeared from Abu Ghraib prison near Baghdad, Iraq, people around the world were shocked. The photos graphically depicted Iraqi prisoners being humiliated, abused, and beaten by U.S. military personnel. In one photo, an Iraqi prisoner stood naked with feces smeared on his face and body. Smiling American soldiers, both male and female, posed alongside the corpse of a beaten Iraqi prisoner, giving the thumbs-

In the international uproar that followed, U.S. political leaders and Defense Department officials scrambled, damage control their priority. “A few bad apples” was the official pronouncement—

Why would ordinary Americans mistreat people like that? How can normal people commit such cruel, immoral acts?

Unless we learn the dynamics of “why,” we will never be able to counteract the powerful forces that can transform ordinary people into evil perpetrators.

—Philip Zimbardo, (2004b)

What actually happened at Abu Ghraib?

At its peak population in early 2004, the Abu Ghraib prison complex housed more than 6,000 Iraqis who had been detained during the American invasion and occupation of Iraq (James, 2008).

There had been numerous reports of mistreatment at Abu Ghraib, including official complaints by the International Red Cross. However, most Americans had no knowledge of the prison conditions until photographs documenting shocking incidents of abuse were shown in the national media (Hersh, 2004a, 2004b).

What factors contributed to the events that occurred at Abu Ghraib prison?

Multiple elements combined to create the conditions for brutality, including in-

The worst incidents took place in a cell block that held the prisoners who had been identified as potential “terrorists” or “insurgents” (Hersh, 2005). The guards were led to believe that it was their patriotic duty to mistreat these potential terrorists in order to help extract useful information (Kelman, 2005; Post, 2011 ; Taguba, 2004). Thinking in this way also helped reduce any cognitive dissonance the soldiers might have been experiencing by justifying the aggression.

Is what happened at Abu Ghraib similar to what happened in Milgram’s studies?

Milgram’s controversial studies showed that even ordinary citizens will obey an authority figure and commit acts of destructive obedience. Some of the accused soldiers, like Army Reserve Private Lynndie England, did claim that they were “just following orders.” Photographs of England, especially the one in which she was holding a naked male prisoner on a leash, created international outrage and revulsion. But England (2004) testified that her superiors praised the photos, saying, “Hey, you’re doing great, keep it up.”

But were the guards “just following orders”?

During the court-

The study that became known as the Stanford Prison Experiment was conducted in 1971 (Haney & others, 1973). Twenty-

Originally, the study was slated to run for two weeks. But after just six days, the situation was spinning out of control. As Zimbardo (2005) recalls, “Within a few days, [those] assigned to the guard role became abusive, red-

While Milgram’s experiments showed the effects of direct authority pressure, the Stanford Prison Experiment demonstrated the powerful influence of situational roles and conformity to implied social rules and norms. These influences are especially pronounced in vague or novel situations where normative social influence is more likely (Zimbardo, 2007). When people are not certain what to do, they tend to rely on cues provided by others and to conform their behavior to that of those in their immediate group (Fiske & others, 2004).

It’s important to note, however, that researchers have questioned whether it was only normative social influence that guided the behavior of the Stanford Prison Experiment participants (Griggs, 2014). For example, some psychologists noted that Zimbardo and his colleagues had been very directive with the guards (Reicher & Haslam, 2006). In 2002, a new study conducted in the United Kingdom was filmed for a show by the British Broadcasting Corporation. In this study, called the BBC Prison Experiment, the guards were not given directions as to how to treat the prisoners. What happened? The guards did not act abusively toward the prisoners. Thus, the researchers concluded that demand characteristics in the form of guidance from the Stanford researchers may have played a role in the abuse in the Stanford study. As you learned in the introduction and research methods chapter, demand characteristics are cues that suggest to participants how they should respond. The psychologists concluded that similar cues may have been present in the “culture” of the Abu Ghraib prison.

At Abu Ghraib, the accused soldiers received no special training and were ignorant of regulations regarding the treatment of civilian detainees or enemy prisoners of war (see James, 2008; Zimbardo, 2007). Guards apparently took their cues from one another and from the military intelligence personnel who encouraged them to “set the conditions” for interrogation (Hersh, 2005; Taguba, 2004).

Other factors might also be at play in situations like Abu Ghraib. For example, researchers found that participants who signed up for a study described to be about prison were more likely to have qualities related to the potential to abuse others—

Are people helpless to resist destructive obedience in a situation like Abu Ghraib prison?

No. As Milgram demonstrated, people can and do resist pressure to perform evil actions. Not all military personnel at Abu Ghraib went along with the pressure to mistreat prisoners (Hersh, 2005; Taguba, 2004). Consider these examples:

Master-

at- Arms William J. Kimbro, a Navy dog handler, adamantly refused to participate in improper interrogations using dogs to intimidate prisoners despite being pressured by military intelligence personnel (Hersh, 2004b). When handed a CD filled with digital photographs depicting prisoners being abused and humiliated, Specialist Joseph M. Darby turned it over to the Army Criminal Investigation Division. It was Darby’s conscientious action that finally prompted a formal investigation of the prison.

At the court-

In fact, as General Peter Pace, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, stated forcefully in a November 2005 press conference, “It is absolutely the responsibility of every U.S. service member, if they see inhumane treatment being conducted, to intervene to stop it.”

Finally, it’s important to point out that understanding the factors that contributed to the events at Abu Ghraib does not excuse the perpetrators’ behavior or absolve them of individual responsibility. And, as Milgram’s research shows, the action of even one outspoken dissenter can inspire others to resist unethical or illegal commands from an authority figure (Packer, 2008a).

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

How might the fundamental attribution error lead people to blame “a few bad apples” rather than noticing situational factors that contributed to the Abu Ghraib prison abuse?

Who should be held responsible for the inhumane conditions and abuse that occurred at Abu Ghraib prison?

Experimenter: It is absolutely essential that you continue.

Mr. Rensaleer: Well, I won’t—

Experimenter: You have no other choice.

Mr. Rensaleer: I do have a choice. (Incredulous and indignant) Why don’t I have a choice? I came here on my own free will. I thought I could help in a research project. But if I have to hurt somebody to do that, or if I was in his place, too, I wouldn’t stay there. I can’t continue. I’m very sorry. I think I’ve gone too far already, probably.

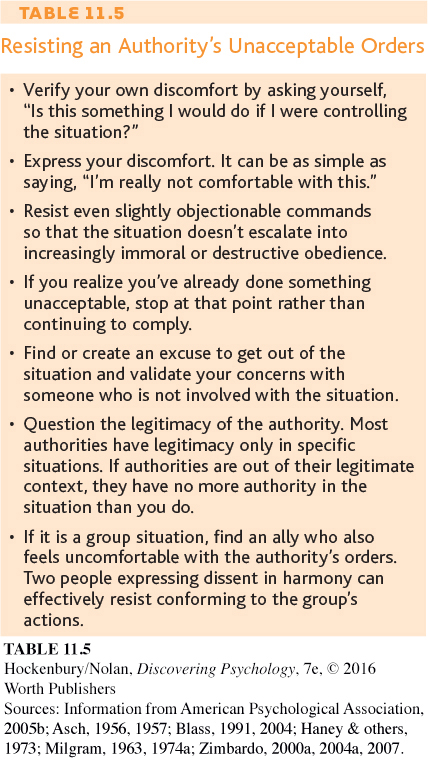

Like some of the other participants in the obedience and conformity studies, Rensaleer effectively resisted the situational and social pressures that pushed him to obey. As did Army Sergeant Joseph M. Darby, who triggered the investigation of abuses at the Abu Ghraib prison camp in Iraq by turning over a CD with photos of the abuse to authorities. As Darby said, the photos “violated everything that I personally believed in and everything that I had been taught about the rules of war.” Table 11.5 summarizes several strategies that can help people resist the pressure to conform or obey in a destructive, dangerous, or morally questionable situation.

How are such people different from those who conform or obey? Unfortunately, there’s no satisfying answer to that question. No specific personality trait consistently predicts conformity or obedience in experimental situations such as those Asch and Milgram created (see Blass, 2000, 2004; Burger, 2009). In other words, the social influences that Asch and Milgram created in their experimental situations can be compelling even to people who are normally quite independent.

Finally, we need to emphasize that conformity and obedience are not completely bad in and of themselves. Quite the contrary. Conformity and obedience are necessary for an orderly society, which is why such behaviors were instilled in all of us as children. The critical issue is not so much whether people conform or obey, because we all do so every day of our lives. Rather, the critical issue is whether the norms we conform to, or the orders we obey, reflect values that respect the rights, well-

Test your understanding of Factors Influencing Conformity and Obedience with  .

.