Altruism and Aggression

HELPING AND HURTING BEHAVIOR

KEY THEME

Prosocial behavior describes any behavior that helps another person, including altruistic acts. Aggression describes behavior that is intended to harm another person.

KEY QUESTIONS

What factors increase the likelihood that people will help a stranger?

What factors decrease the likelihood that people will help a stranger?

How can the lack of bystander response in the Genovese murder case be explained in light of psychological research on helping behavior?

What factors increase the likelihood that people will harm another person?

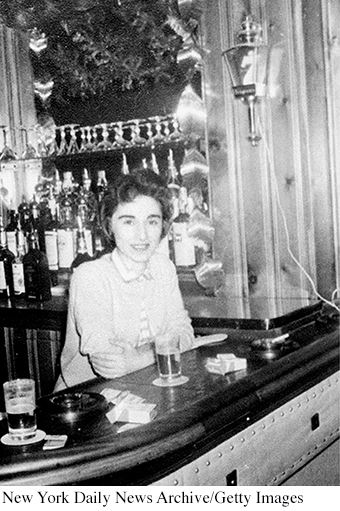

It was about 3:20 A.M. on Friday, March 13, 1964, when 28-

As she got out of her car, she noticed a man at the end of the parking lot. When the man moved in her direction, she began walking toward a nearby police call box, which was under a streetlight in front of a bookstore. On the opposite side of the street was a 10-

“Let that girl alone!” a man yelled from one of the upper apartment windows. The attacker looked up, then walked off, leaving Kitty on the ground, bleeding. The street became quiet. Minutes passed. One by one, lights went off. Struggling to her feet, Kitty made her way toward her apartment. As she rounded the corner of the building moments later, her assailant returned, stabbing her again. “I’m dying! I’m dying!” she screamed.

Again, lights went on. Windows opened and people looked out. This time, the assailant got into his car and drove off. It was now 3:35 A.M. Fifteen minutes had passed since Kitty’s first screams for help. A New York City bus passed by. Staggering, then crawling, Kitty moved toward the entrance of her apartment. She never made it. Her attacker returned, searching the apartment entrance doors. At the second apartment entrance, he found her, slumped at the foot of the steps. This time, he stabbed her to death.

It was 3:50 A.M. when someone first called the police. The police took just two minutes to arrive at the scene. About half an hour later, an ambulance carried Kitty Genovese’s body away. Only then did people come out of their apartments to talk to the police.

Over the next two weeks, police investigators learned that a total of 38 people had witnessed Kitty’s murder—

When The New York Times interviewed various experts, they seemed baffled, although one expert said it was a “typical” reaction (Mohr, 1964). If there was a common theme in their explanations, it seemed to be “apathy.” The occurrence was simply representative of the alienation and depersonalization of life in a big city, people said (see Rosenthal, 1964a, 1964b).

Not everyone bought this pat explanation. In the first place, it wasn’t true. As social psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley (1970) later pointed out in their landmark book, The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn’t He Help?:

People often help others, even at great personal risk to themselves. For every “apathy” story, one of outright heroism could be cited. . . . People sometimes help and sometimes don’t. What determines when help will be given?

That’s the critical question, of course. When do people help others? And why do people help others?

When we help another person with no expectation of personal benefit, we’re displaying altruism (Batson & others, 2011). An altruistic act is fundamentally selfless—

Altruistic actions fall under the broader heading of prosocial behavior, which describes any behavior that helps another person, whatever the underlying motive. Note that prosocial behaviors are not necessarily altruistic. Sometimes we help others out of guilt. And, sometimes we help others in order to gain something, such as recognition, rewards, increased self-

Factors That Increase the Likelihood of Bystanders Helping

Kitty Genovese’s death triggered hundreds of investigations into the conditions under which people will help others (Dovidio, 1984; Dovidio & others, 2006). Those studies began in the 1960s with the pioneering efforts of Bibb Latané and John Darley, who conducted a series of ingenious experiments in which it appears that help is needed. For example, in one study, participants believed they were overhearing an epileptic seizure (Darley & Latané, 1968). In another study, participants were in a room that started to fill with smoke (Latané & Darley, 1968). Based on these studies, Latané and Darley concluded that people must pass through three stages before they offer help. First, they must notice an emergency situation. Second, they must interpret it as a situation that actually requires help. Third, they must decide that it is their responsibility to offer help (Latané & Darley, 1968).

Other researchers joined the effort to understand what factors influence a person’s decision to help another (see Dovidio & others, 2006; Fischer & others, 2011; Zaki & Mitchell, 2013). Some of the most significant factors that increase the likelihood of helping include:

The “feel good, do good” effect. People who feel good, successful, happy, or fortunate are more likely to decide to help others (see Forgas & others, 2008; C. Miller, 2009). Those good feelings can be due to virtually any positive event, such as succeeding at a task or even just enjoying a warm, sunny day.

Feeling guilty. We tend to be more helpful when we’re feeling guilty. For example, after telling a lie or inadvertently causing an accident, people were more likely to decide to help others (Basil & others, 2006; Cohen & others, 2012; de Hooge & others, 2011).

Seeing others who are willing to help. Whether it’s donating blood or helping a stranded motorist change a flat tire, we’re more likely to decide to help if we observe others do the same (Fischer & others, 2011). This is true even when we are the recipient of help (Tsvetkova & Macy, 2014).

Perceiving the other person as deserving help. We’re more likely to decide to help people who are in need of help through no fault of their own. For example, people are twice as likely to give some change to a stranger if they believe the stranger’s wallet has been stolen than if they believe the stranger has simply spent all his money (Burn, 2009; Laner & others, 2001; Latané & Darley, 1970). Similarly, people are more likely to support welfare programs if they believe that the welfare recipients are actively trying to find a job (Petersen & others, 2012).

Knowing how to help. Research has confirmed that knowing what to do and being physically capable of helping contributes greatly to the decision to help someone else (Fischer & others, 2011; Steg & de Groot, 2010). In line with this, some universities have implemented bystander training to give students skills to intervene, for example, to prevent a sexual assault (Hua, 2013; University of Arizona, n.d.).

A personalized relationship. When people have any sort of personal relationship with another person, even at the level of simply making eye contact with someone, they’re more likely to decide to help that person (Solomon & others, 1981; Vrugt & Vet, 2009). This might explain why researchers have observed that people are less likely to help in anonymous online contexts than in the “real world” (Barlin´ska & others, 2013). When online interactions are not anonymous, a personal relationship makes people more likely to help, for example in cyber-

bullying situations (Machác˘ ková & others, 2013). Page 485A dangerous situation. People also are more likely to decide to help in dangerous situations—

those that are clearly an emergency, those when the perpetrator is present, and those that present a physical risk to the helper (Fischer & others, 2011). Even in an online context, bystanders are more likely to intervene in cyberbullying when it is more severe (Bastiaensens, & others, 2014). These findings might seem surprising, but it may be that these are situations in which it is clear that help is needed.

Factors That Decrease the Likelihood of Bystanders Helping

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that people are more likely to help others if they are the only ones available to help?

Unfortunately, instances in which bystanders fail to intervene are still regularly reported. For example, during spring break revels on a Florida beach, police reported a gang rape that occurred while hundreds of people watched (Southall, 2015). And in Philadelphia, when a woman on a bus passed out, evidently from drug or alcohol use, bystanders just filmed the situation while her young daughter tried to rouse her (Gambacorta, 2014). A police official said, “There’s very little reason why 15 calls to 9-

Given examples like these and many others, it’s important to consider influences that decrease the likelihood of helping behavior. As we look at some of the key findings, we’ll also note how each factor might have played a role in the death of Kitty Genovese.

The presence of other people. In general, people are much more likely to decide to help when they are alone (Fischer & others, 2011; Latané & Nida, 1981). If other people are present or imagined, helping behavior declines—

a phenomenon called the bystander effect. This effect has even been observed in five- year- old children. One study found that children were more likely to help a teacher when they were alone or when the only other children present were behind a barrier and physically unable to help (Plötner & others, 2015).

There seem to be two major reasons for the bystander effect. First, the presence of other people creates a diffusion of responsibility. The responsibility to intervene is shared (or diffused) among all the onlookers. Because no one person feels all the pressure to respond, each bystander becomes less likely to help.

Ironically, the sheer number of bystanders seemed to be the most significant factor working against Kitty Genovese. Remember that when she first screamed, a man yelled down, “Let that girl alone!” With that, each observer instantly knew that he or she was not the only one watching the events on the street below. Hence, no single individual felt the full responsibility to help.

Second, the bystander effect seems to occur because each of us is motivated to some extent by the desire to behave in a socially acceptable way (normative social influence) and to appear correct (informational social influence). In the case of Kitty Genovese, the lack of intervention by any of the witnesses may have signaled the others that intervention was not appropriate, wanted, or needed.

Being in a big city or a very small town. Kitty Genovese was attacked late at night in one of the biggest cities in the world. Research by Robert Levine and his colleagues (2008) confirmed that people are less likely to decide to help strangers in big cities, but other aspects of city life, like crowding and economic status, also affect helping. On the other hand, people are also less likely to help a stranger in towns with populations under 5,000 (Steblay, 1987).

Page 486Vague or ambiguous situations. When situations are ambiguous and people are not certain that help is needed, they’re less likely to decide to offer help (Solomon & others, 1978). The ambiguity of the situation may also have worked against Kitty Genovese. The people in the apartment building saw a man and a woman struggling on the street below but had no way of knowing whether the two were acquainted. “We thought it was a lovers’ quarrel,” some of the witnesses later said (Gansberg, 1964). Researchers have found that people are especially reluctant to intervene when the situation appears to be a domestic dispute, because they are not certain that assistance is wanted (Gracia & others, 2009). In a recent incident in Jersey City, NJ, a woman was fatally stabbed by her ex-

boyfriend. A neighbor who heard the attack reportedly “went back to bed, not wanting to get involved” in what he likely perceived as a domestic dispute (Villanova, 2014). When the personal costs for helping outweigh the benefits. As a general rule, we tend to weigh the costs as well as the benefits of helping in deciding whether to act. If the potential costs outweigh the benefits, it’s less likely that people will help (Fischer & others, 2006, 2011). The witnesses in the Genovese case may have felt that the benefits of helping Genovese were outweighed by the potential hassles and danger of becoming involved in the situation.

On a small yet universal scale, the murder of Kitty Genovese dramatically underscores the power of situational and social influences to affect our behavior. Although social psychological research has provided insights about the factors that influenced the behavior of those who witnessed the Genovese murder, it should not be construed as a justification for the inaction of the bystanders. After all, Kitty Genovese’s death probably could have been prevented by a single phone call. If we understand the factors that decrease helping behavior, we can recognize and overcome those obstacles when we encounter someone who needs assistance. If you had been Kitty Genovese—

Aggression

HURTING BEHAVIOR

The flip side of helping behavior is hurting behavior, or aggression—any verbal or physical behavior intended to cause harm to other people. To be classified as aggression, the aggressor must believe that their behavior is harmful to the other person, and the other person must not wish to be harmed (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). A child who hits her little brother, a mugger who threatens his victim, a boss who screams at her subordinates, or a terrorist who fires shots in a crowded mall—

Have you ever wondered about the wide variation in aggressive tendencies? Why does one friend threaten a fistfight when provoked, while another calmly walks away? Like helping behavior, hurting behavior is driven by a range of factors—

THE INFLUENCE OF BIOLOGY ON AGGRESSION

Researchers have long thought that our tendency to behave aggressively has a biological component. Biological theories of aggression include genetic, structural, and biochemical explanations.

The Influence of Genes and Brain Structure When someone behaves aggressively, how do we know if that is driven, even in part, by inborn personality characteristics? There have been a number of studies that tried to separate the effects of genes and environmental influences in rates of aggression. For example, one study found that identical twins had similar aggressive tendencies whether or not they were raised together. Because twins share 100% of their genes, this finding indicates a strong genetic influence on aggressive behavior (Bouchard & others, 1990; Segal, 2012). Two meta-

The presence of behaviors that appear to be driven, at least in part, by genetics leads to questions about whether these behaviors have an evolutionary basis. That is, are there adaptive benefits to having a genetic predisposition toward aggression, at least in certain contexts? Evolutionary theorists say yes (Ferguson & Beaver, 2009). Aggression, they assert, can help people to acquire or secure resources for themselves and for those who share their genes (Buss & Duntley, 2006).

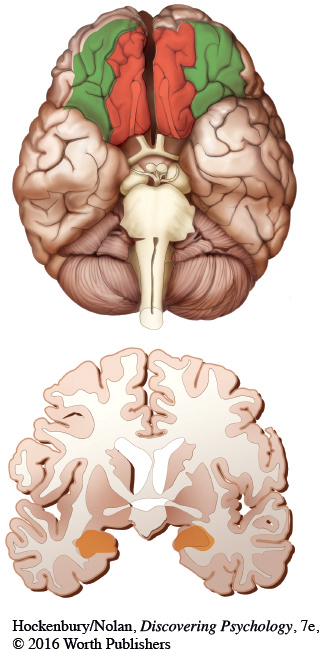

Another biological explanation for aggression points to differences in the parts of the brain that regulate emotion, including the amygdala, the prefrontal cortex, and the limbic system (Bobes & others, 2013; Davidson & others, 2000; Meyer-

Biochemical Influences Biochemical influences on aggression include the hormone testosterone and alcohol abuse. For example, Irene van Bokhoven and her colleagues (2006) followed 96 boys from kindergarten through age 21. They found that boys who had higher levels of testosterone over this period were more likely to have criminal records as adults. This tendency is not limited to men. Both male and female college students who had committed acts of violence or engaged in drug use were found to have higher rates of testosterone (Banks & Dabbs, 1996). And a link between testosterone and aggression has been found among female prisoners (Dabbs & Hargrove, 1997).

However, it’s important not to overstate the link between testosterone and aggression. In a meta-

Although most people who consume alcohol are not violent, the rate of violence is higher among those under the influence of alcohol than among those who have not consumed alcohol (Duke & others, 2011; Pedersen & others, 2014). This effect has been established in both laboratory and everyday settings (Chermack & Taylor, 1995; Exum, 2006; Graham & others, 2006). One research team bravely spent over 1,000 nights in over 100 bars in Toronto, Canada, and logged more than 1,000 violent incidents. As the crowd became more intoxicated, aggressive incidents were more likely to occur. And, the aggressive person’s level of intoxication was generally related to the severity of the violent act (Graham & others, 2006).

PSYCHOLOGICAL INFLUENCES ON AGGRESSION

While it’s clear that there are biological influences on aggression, there also are psychological influences. For example, a great deal of aggressive behavior is learned. In addition, there are situational factors that can increase people’s tendency to be aggressive.

Learning People who are violent are often mimicking behavior they have seen, a form of observational learning. For example, in Chapter 5, you read about Albert Bandura’s classic Bobo Doll experiments in which children learned to behave aggressively toward a large balloon doll by watching a brief video in which an adult did the same. Exposure to violence may also lead to aggression over the longer term. Researchers have found that both women and men exposed to violence in their families while growing up were more likely to abuse their partners and their children as adults (Heyman & Smith Slep, 2002). But a higher likelihood is not a guarantee that the family pattern of violence will be repeated. In fact, most people who were exposed to violence as children do not grow up to be abusers themselves.

There also is evidence that exposure to violence in the media—

In the Critical Thinking box “Does Exposure to Media Violence Cause Aggressive Behavior” in Chapter 5, you read about the evidence that viewing media violence is related to aggressive behavior (see Bushman & others, 2009). Viewing pornography, especially pornography depicting sexual violence, also has been linked to increased aggressive attitudes toward women (Hald & others, 2010). Although there is a strong link, it’s important to note that much of the research connecting media violence to actual aggressive behavior is correlational. Remember from Chapter 1 that correlational studies cannot tell us whether one variable, such as viewing pornography, causes another, such as aggression. The research that is experimental and could show causal links is primarily in artificial situations (Ferguson & Kilbourn, 2009).

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that there is a link between aggression and listening to violent music lyrics?

Other forms of violent media, like violent video games, also have been linked to increased aggression. For example, one study followed more than 1,000 boys and girls throughout their high school years, and found that students who played violent video games throughout this time showed increases in aggressive behavior over the four years of the study (Willoughby & others, 2012). Listening to violent music lyrics—

Frustration Aggression can be learned, but it can also be driven by situational factors that are annoying or frustrating. For example, researchers have identified high temperatures as a source for frustration-

When frustrated by a stressful situation or an annoying person, people can react aggressively (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). Jodi Whitaker and her colleagues (2013) conducted an experiment in which they created a situation that would be incredibly frustrating to their student participants. The students were invited to take an extremely difficult history test that could earn them desirable snacks for a top performance. Some students were then “mistakenly” given access to the answers—

When’s the last time you got really frustrated or angry? If you drive, it might have been behind the wheel. About one third of us admit to having been the aggressor in a road rage situation, and that’s particularly true of younger drivers and male drivers (Smart & others, 2003). Road rage results from a number of factors, especially frustration—

GENDER, CULTURE, AND AGGRESSION

Quick—

Why are men more likely than women to behave in physically aggressive ways? There may be biological reasons. Evolutionary theorists suggest that the gender difference is due to the fact that men are more likely to reproduce if they have access to desirable mating partners, something that is more likely for men with resources—

But there also are environmental explanations. The ways in which girls and boys exhibit aggression are influenced by the reactions of others. Children learn aggression-

Cultural factors also influence aggressive behavior and attitudes. Aggression and violence seem to be more common in certain types of societies (Bond, 2004). These include societies that are less economically developed, that have higher levels of economic inequality, and that are not democracies (Bond, 2004). Researchers have also found that there are regional and national differences in certain types of aggression based on the concept of a culture of honor (Vandello & others, 2008). A culture of honor is one in which actions perceived as damaging your reputation must be addressed (Vandello & Cohen, 2004). In some countries, such as Turkey, the culture of honor is focused on offenses against one’s family (Cihangir, 2013; van Osch & others, 2013).

In the Americas, especially the southern United States and Latin America, the culture of violence tends to be based on masculine honor. Psychologist Joseph Vandello and his colleagues (2008) describe masculine honor as having “an emphasis on masculinity and male toughness.” In such cultures, violence that is seen as helping a man restore his reputation is more acceptable. For example, if a man is mocked at a sporting event, a violent response might be seen as reasonable or even admirable (Vandello & Cohen, 2003). Masculine honor culture, although usually regional, can also be contextual. Some researchers have observed an aggression-

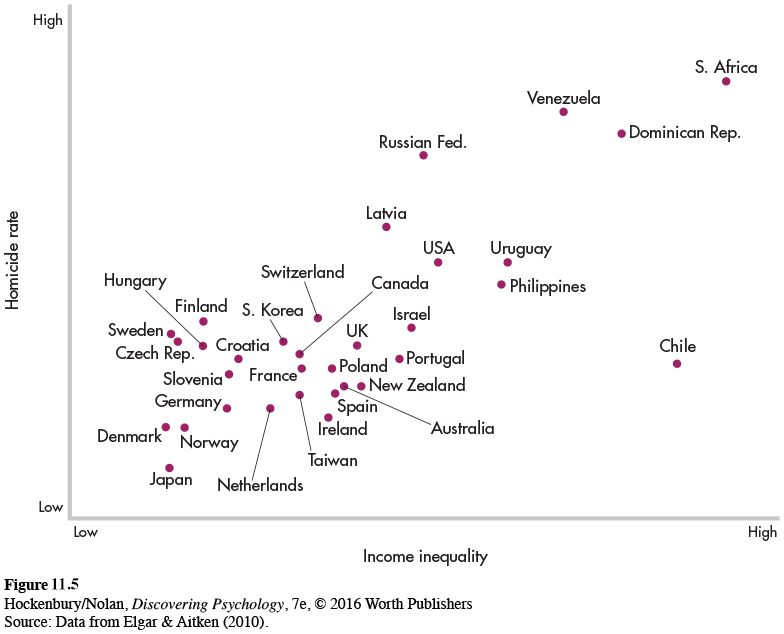

Cultures with significant income inequality also have higher rates of aggression. Researchers have identified a strong link between income inequality and violence, particularly murder (Nivette, 2011; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). For example, a study of 33 countries found a very high correlation of 0.80 between the level of income inequality in a country and the homicide rate (Elgar & Aitken, 2010; see Figure 11.5). From Chapter 1, you may remember that the highest possible correlation is 1.00, indicating that two variables are perfectly related. A correlation of 0.80 is close to the highest you would see in social science research. Just the fact that this important cultural element is so tightly bound with extreme violence is an indication that sociocultural factors, in addition to biological and psychological factors, are important predictors of violence.

Test your understanding of Altruism and Aggression with  .

.