Coping

HOW PEOPLE DEAL WITH STRESS

KEY THEME

Coping refers to the ways in which we try to change circumstances, or our interpretation of circumstances, to make them less threatening.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the two basic forms of coping, and when is each form typically used?

What are some of the most common coping strategies?

How does culture affect coping style?

Think about some of the stressful periods that have occurred in your life. What kinds of strategies did you use to deal with those distressing events? Which strategies seemed to work best? Did any of the strategies end up working against your ability to reduce the stressor? If you had to deal with the same events again today, would you do anything differently?

For example, imagine that you discovered that you weren’t allowed to register for classes because the financial aid office had lost your paperwork. How would you react? What would you do?

The strategies that you use to deal with distressing events are examples of coping. Coping refers to the ways in which we try to change circumstances, or our interpretation of circumstances, to make them more favorable and less threatening (Folkman, 2009).

When coping is effective, we adapt to the situation and stress is reduced. Unfortunately, coping efforts do not always help us adapt. Maladaptive coping can involve thoughts and behaviors that intensify or prolong distress, or that produce self-

Adaptive coping responses serve many functions (Folkman, 2009; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2007). Most important, adaptive coping involves realistically evaluating the situation and determining what can be done to minimize the impact of the stressor. But adaptive coping also involves dealing with the emotional aspects of the situation. In other words, adaptive coping often includes developing emotional tolerance for negative life events, maintaining self-

Traditionally, coping has been broken down into two major categories: problem-

Problem-Focused Coping Strategies

CHANGING THE STRESSOR

Problem-

Sandy’s friend Wyncia, whose own house narrowly escaped the flames, demonstrated the value of problem-

Wyncia said, “When you experience that gut ‘fight-

Planful problem solving involves efforts to rationally analyze the situation, identify potential solutions, and then implement them. In effect, you take the attitude that the stressor represents a problem to be solved. Once you assume that mental stance, you follow the basic steps of problem solving (see Chapter 7).

When people tackle a problem head on, they are engaging in confrontive coping. Ideally, confrontive coping is direct and assertive but not hostile or angry. When it is hostile or aggressive, confrontive coping may well generate negative emotions in the people being confronted, damaging future relations with them (Folkman & Lazarus, 1991). However, if you recall our earlier discussion of hostility, then you won’t be surprised to find that hostile individuals often engage in confrontive coping (Vandervoort, 2006).

Emotion-Focused Coping Strategies

CHANGING YOUR REACTION TO THE STRESSOR

When the stressor is one over which we can exert little or no control, we often focus on the dimension of the situation that we can control—

When you shift your attention away from the stressor and toward other activities, you’re engaging in the emotion-

Because you are focusing your attention on something other than the stressor, escape–

In the long run, escape–

Seeking social support is the coping strategy that involves turning to friends, relatives, or other people for emotional, tangible, or informational support. As we discussed earlier in the chapter, having a strong network of social support can help buffer the impact of stressors (Uchino, 2009). Confiding in a trusted friend gives you an opportunity to vent your emotions and better understand the stressful situation.

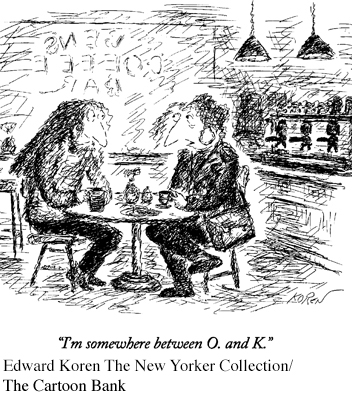

When you acknowledge the stressor but attempt to minimize or eliminate its emotional impact, you’re engaging in the coping strategy called distancing. Having an attitude of joy and lightheartedness in daily life, and finding the humor in life’s absurdities or ironies, is one form of distancing (Kuhn & others, 2010; McGraw & others, 2013). Sometimes people emotionally distance themselves from a stressor by discussing it in a detached, depersonalized, or intellectual way.

For example, when Andi planned her first trip up to her burned-

Nemcova founded Happy Hearts Fund, an international foundation that has raised tens of millions of dollars and founded schools and clinics in areas hit by natural disasters around the world, including Thailand, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Nemcova is shown here at the opening of a kindergarten in an Indonesian village that was devastated by a powerful earthquake.

In certain high-

In contrast to distancing, denial is a refusal to acknowledge that the problem even exists. Like escape–

Perhaps the most constructive emotion-

For example, as Andi said, “Your life is terrible and wonderful at the same time. It’s terrible because you’ve lost everything you own. But it’s wonderful because you see the incredible kindness of strangers.”

Some people turn to their religious or spiritual beliefs to help them cope with stress. Positive religious coping includes seeking comfort or reassurance in prayer or from a religious community, or believing that your personal experience is spiritually meaningful. Positive religious coping is generally associated with lower levels of stress and anxiety, improved mental and physical health, and enhanced well-

On the other hand, religious beliefs can also lead to a less positive outcome. Individuals who respond with negative religious coping, in which they become angry, question their religious beliefs, or believe that they are being punished, tend to experience increased levels of distress, poorer health, and decreased well-

For many people, religious coping offers a sense of control or certainty during stressful events or circumstances (Hogg & others, 2010; Kay & others, 2010). For example, some people find strength in the notion that adversity is a test of their religious faith or that they have been given a particular challenge in order to fulfill a higher moral purpose. For some people, religious or spiritual beliefs can increase resilience, optimism, and personal growth during times of stress and adversity (Pargament & Cummings, 2010).

IN FOCUS

Gender Differences in Responding to Stress: “Tend-

Physiologically, men and women show the same hormonal and sympathetic nervous system activation that Walter Cannon (1932) described as the “fight-

To illustrate, consider this finding: When men come home after a stressful day at work, they tend to withdraw from their families, wanting to be left alone—

As we have noted in this chapter, women tend to be much more involved in their social networks than men. And, as compared to men, women are much more likely to seek out and use social support when they are under stress. Throughout their lives, women tend to mobilize social support—

Why the gender difference in coping with stress? Health psychologists Shelley Taylor and her colleagues (Taylor & others, 2000; Taylor & Gonzaga, 2007) believe that evolutionary theory offers some insight. According to the evolutionary perspective, the most adaptive response in virtually any situation is one that promotes the survival of both the individual and the individual’s offspring (Taylor & Master, 2011). Given that premise, neither fighting nor fleeing is likely to have been an adaptive response for females, especially females who were pregnant, nursing, or caring for their offspring. According to Taylor (2006), “Tending to offspring in times of stress would be vital to ensuring the survival of the species.” Rather than fighting or fleeing, they argue, women developed a tend-

What is the “tend-

The “befriending” side of the equation relates to women’s tendency to seek social support during stressful situations. Befriending is the creation and maintenance of social networks that provide resources and protection for the female and her offspring under conditions of stress (Taylor & Master, 2011).

However, both males and females show the same neuroendocrine responses to an acute stressor—

In combination, all of these oxytocin-

Think Like a SCIENTIST

Can you reduce your stress level by watching cute animal videos? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Coping with Stress.

Finally, it’s important to note that there is no single “best” coping strategy. In general, the most effective coping is flexible, meaning that we fine-

Although it’s virtually inevitable that you’ll encounter stressful circumstances, there are coping strategies that can help you minimize their health effects. We suggest several techniques in the Psych for Your Life section at the end of the chapter.

Culture and Coping Strategies

Culture can influence the choice of coping strategies (Chun & others, 2006). Americans and other members of individualistic cultures tend to emphasize personal autonomy and personal responsibility in dealing with problems. Thus, they are less likely to seek social support in stressful situations than are members of collectivistic cultures, such as Asian cultures (Wong & Wong, 2006). Members of collectivistic cultures tend to be more oriented toward their social group, family, or community and toward seeking help with their problems (Kuo, 2013).

Individualists also tend to emphasize the importance and value of exerting control over their circumstances, especially circumstances that are threatening or stressful (O’Connor & Shimizu, 2002). Thus, they favor problem-

In collectivistic cultures, however, a greater emphasis is placed on controlling your personal reactions to a stressful situation rather than trying to control the situation itself (Zhou & others, 2012). According to some researchers, people in China, Japan, and other Asian cultures are more likely to rely on emotional coping strategies than people in individualistic cultures. Coping strategies that are particularly valued in collectivistic cultures include emotional self-

For example, the Japanese emphasize accepting difficult situations with maturity, serenity, and flexibility (Gross, 2007). Common sayings in Japan are “The true tolerance is to tolerate the intolerable” and “Flexibility can control rigidity.” Along with controlling inner feelings, many Asian cultures also stress the goal of controlling the outward expression of emotions, however distressing the situation (Park, 2010).

These cultural differences in coping underscore the point that there is no formula for effective coping in all situations. That we use multiple coping strategies throughout almost every stressful situation reflects our efforts to identify what will work best at a given moment in time. To the extent that any coping strategy helps us identify realistic alternatives, manage our emotions, and maintain important relationships, it is adaptive and effective.

Test your understanding of Coping: How People Deal with Stress with  .

.