Fear and Trembling

ANXIETY DISORDERS, POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER, AND OBSESSIVE–

KEY THEME

Intense anxiety that disrupts normal functioning is an essential feature of the anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and obsessive–

KEY QUESTIONS

How does pathological anxiety differ from normal anxiety?

What characterizes generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder?

What are the phobias, and how have they been explained?

Anxiety is a familiar emotion to all of us—

Anxiety has both physical and mental effects. As your internal alarm system, anxiety puts you on physical alert, preparing you to defensively “fight” or “flee” potential dangers. Anxiety also puts you on mental alert, making you focus your attention squarely on the threatening situation. You become extremely vigilant, scanning the environment for potential threats. When the threat has passed, your alarm system shuts off and you calm down. But even if the problem persists, you can normally put your anxious thoughts aside temporarily and attend to other matters.

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that the less anxiety you have, the better?

In the anxiety disorders, however, the anxiety is maladaptive, disrupting everyday activities, moods, and thought processes. It’s as if you’ve triggered a faulty car alarm that activates at the slightest touch and has a broken “off “ switch.

Three features distinguish normal anxiety from pathological anxiety. First, pathological anxiety is irrational. The anxiety is provoked by perceived threats that are exaggerated or nonexistent, and the anxiety response is out of proportion to the actual importance of the situation. Second, pathological anxiety is uncontrollable. The person can’t shut off the alarm reaction, even when he or she knows it’s unrealistic.

And third, pathological anxiety is disruptive. It interferes with relationships, job or academic performance, or everyday activities. In short, pathological anxiety is unreasonably intense, frequent, persistent, and disruptive (Beidel & Stipelman, 2007; Woo & Keatinge, 2008).

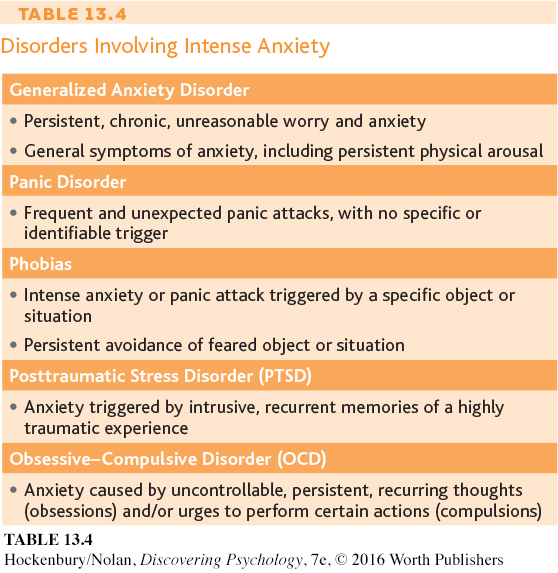

As a symptom, anxiety occurs in many different psychological disorders. In the anxiety disorders, however, anxiety is the main symptom, although it is manifested differently in each of the disorders. Other disorders with anxiety as a symptom include posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive–

Disorders that include anxiety—

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

WORRYING ABOUT ANYTHING AND EVERYTHING

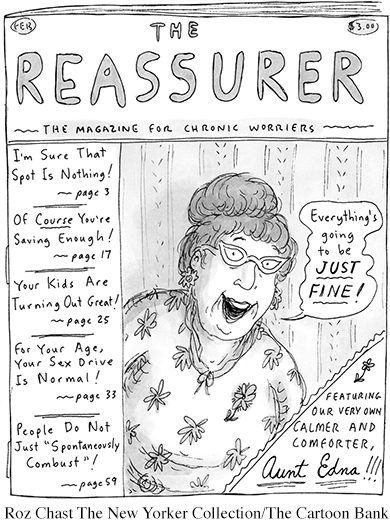

Global, persistent, chronic, and excessive apprehension is the main feature of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). People with this disorder are constantly tense and anxious, and their anxiety is pervasive. They feel anxious about a wide range of life circumstances, sometimes with little or no apparent justification (Craske & Waters, 2005; Sanfelippo, 2006). The more issues about which a person worries excessively, the more likely it is that he or she suffers from generalized anxiety disorder (DSM-

Normally, anxiety quickly dissipates when a threatening situation is resolved. In generalized anxiety disorder, however, when one source of worry is removed, another quickly moves in to take its place. The anxiety can be attached to virtually any object or to none at all. Because of this, generalized anxiety disorder is sometimes referred to as free-

EXPLAINING GENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER

What causes generalized anxiety disorder? As is true with most psychological disorders, environmental, psychological, and genetic as well as other biological factors are probably involved in GAD (Payne & others, 2014; Stein & Steckler, 2010). For example, a brain that is “wired” for anxiety can give a person a head start toward developing GAD in later life, but problematic relationships and stressful experiences can make the possibility more likely. Signs of problematic anxiety can be evident from a very early age, such as in the example of a child with a very shy temperament who consistently feels overwhelming anxiety in new situations or when separated from his parents. In some cases, such children develop anxiety disorders such as GAD in adulthood (Creswell & O’Connor, 2011; Weems & Silverman, 2008).

Panic Attacks and Panic Disorders

SUDDEN EPISODES OF EXTREME ANXIETY

Generalized anxiety disorder is like the dull ache of a sore tooth—

Sometimes panic attacks occur after a stressful experience, such as an injury or illness, or during a stressful period of life, such as while changing jobs or during a period of marital conflict (Moitra & others, 2011). Experiences of bereavement, separation from significant others, and interpersonal loss are among the experiences most often associated with triggering panic attacks (Klauke & others, 2010). In other cases, however, panic attacks seem to come from nowhere.

When panic attacks occur frequently and unexpectedly, the person is said to be suffering from panic disorder. In this disorder, the frequency of panic attacks is highly variable and quite unpredictable. One person may have panic attacks several times a month. Another person may go for months without an attack and then experience panic attacks for several days in a row. Understandably, people with panic disorder are quite apprehensive about when and where the next panic attack will hit (Craske & Waters, 2005; Good & Hinton, 2009).

Some panic disorder sufferers go on to develop agoraphobia. Agoraphobia involves fear of suffering a panic attack or other embarrassing or incapacitating symptoms in a place from which escape would be difficult or impossible (DSM-

Your author Susan treated a number of people with agoraphobia while working in an outpatient clinic for people with panic disorders. For example, Anya, a 32-

EXPLAINING PANIC DISORDER

People with panic disorder are often hypersensitive to the signs of physical arousal (Schmidt & Keough, 2010; Zvolensky & Smits, 2008). The fluttering heartbeat or momentary dizziness that the average person barely notices signals disaster to the panic-

People with panic disorder may also be victims of their own illogical thinking. According to the catastrophic cognitions theory, people with panic disorder are not only oversensitive to physical sensations, they also tend to catastrophize the meaning of their experience (Good & Hinton, 2009; Hinton & Hinton, 2009). A few moments of increased heart rate after climbing a flight of stairs is misinterpreted as the warning signs of a heart attack. Such catastrophic misinterpretations simply add to the physiological arousal, creating a vicious circle in which the frightening symptoms intensify.

Syndromes resembling panic disorder have been reported in many cultures (Chentsova-

The Phobias

FEAR AND LOATHING

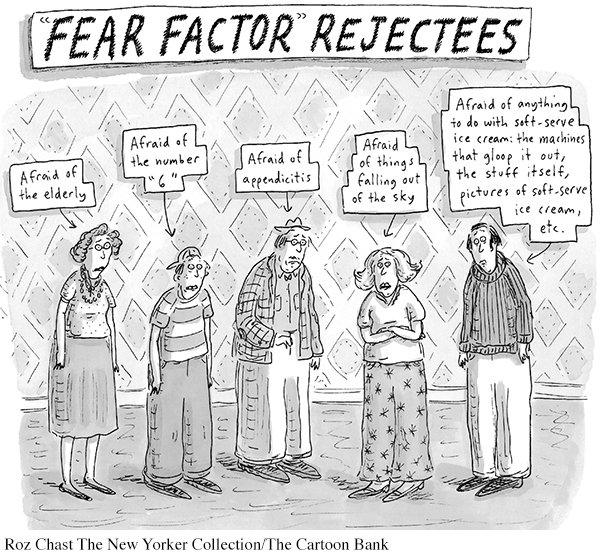

A phobia is a persistent and irrational fear of a specific object, situation, or activity. In the general population, mild irrational fears that don’t significantly interfere with a person’s ability to function are very common. Many people are fearful of certain animals, such as dogs or snakes, or are moderately uncomfortable in particular situations, such as flying in a plane or riding in a glass elevator. Nonetheless, many people cope with such fears without being overwhelmed with anxiety. As long as the fear doesn’t interfere with their daily functioning, they would not be diagnosed with a psychological disorder.

In comparison, people with specific phobia, formerly called simple phobia, are more than just terrified of a particular object or situation. In some people, encountering the feared situation or object can provoke a full-

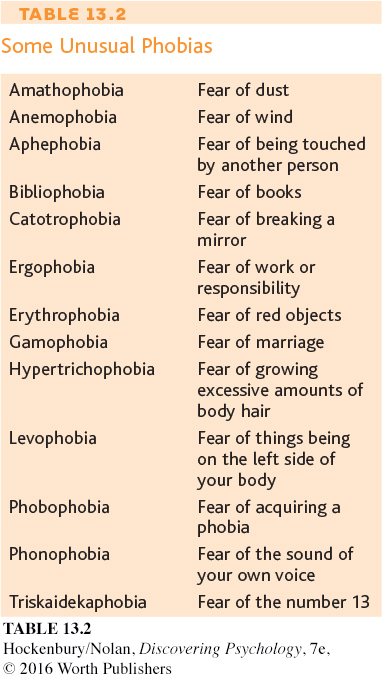

About 13 percent of the general population experiences a specific phobia at some time in their lives (Kessler & others, 2005a). More than twice as many women as men suffer from specific phobia. Occasionally, people have unusual phobias. (See Table 13.2). Oprah Winfrey, for example, has been afraid of chewing gum since she was a child, when her grandmother left used gum around the house. In an interview with Jamie Foxx, she told him: “When I saw you chewing on Oscar night, I freaked out” (O Magazine, 2005). Generally, the objects or situations that produce specific phobias tend to fall into four categories:

Fear of particular situations, such as flying, driving, tunnels, bridges, elevators, crowds, or enclosed places

Fear of features of the natural environment, such as heights, water, thunder-

storms, or lightning Fear of injury or blood, including the fear of injections, needles, and medical or dental procedures

Fear of animals and insects, such as snakes, spiders, dogs, cats, slugs, or bats

SOCIAL ANXIETY DISORDER

FEAR OF BEING JUDGED IN SOCIAL SITUATIONS

A second type of phobia also deserves additional comment. Social anxiety disorder is one of the most common psychological disorders and is more prevalent among women than men (Altemus, 2006; Kessler & others, 2005b). Social anxiety disorder goes well beyond the shyness that everyone sometimes feels at social gatherings. Rather, the person with social anxiety disorder is paralyzed by fear of social situations in which she may be judged by others. Eating a meal in public, making small talk at a party, or using a public restroom can be agonizing for the person with social anxiety disorder.

The core of social anxiety disorder seems to be an irrational fear of being critically evaluated by others. Some, but not all, people with social anxiety disorder recognize that their fear is excessive and irrational. Even so, they approach social situations with tremendous dread and anxiety (Kashdan & others, 2013). In severe cases, they may even suffer a panic attack in social situations. When the fear of being judged by others in social situations significantly interferes with daily life, social anxiety disorder may be present (DSM-

As with panic attacks, cultural influences can add some novel twists to social anxiety disorder. Consider taijin kyofusho, a disorder that usually affects young Japanese males. It has several features in common with social anxiety disorder, including extreme social anxiety and avoidance of social situations. However, the person with taijin kyofusho is not worried about being embarrassed in public. Rather, reflecting the cultural emphasis of concern for others, the person with taijin kyofusho fears that his appearance or smell, facial expression, or body language will offend, insult, or embarrass other people (Iwamasa, 1997; Norasakkunkit & others, 2012).

EXPLAINING PHOBIAS

LEARNING THEORIES

The development of some phobias can be explained in terms of basic learning principles (Craske & Waters, 2005). Classical conditioning may well be involved in the development of a specific phobia that can be traced back to some sort of traumatic event. In Chapter 5 on learning, we saw how psychologist John Watson classically conditioned “Little Albert” to fear a tame lab rat that had been paired with loud noise. Following the conditioning, the infant’s fear generalized to other furry objects.

More recently, researchers demonstrated the role of classical conditioning in the development of phobias by pairing something new, like an invented cartoon character named Spardi, with something frightening, like a picture of a woman being mugged at knife-

Operant conditioning can also be involved in the avoidance behavior that characterizes phobias. In Michelle’s case, she quickly learned that she could reduce her anxiety and fear by avoiding dogs altogether. To use operant conditioning terms, her operant response of avoiding dogs is negatively reinforced by the relief from anxiety and fear that she experiences.

Observational learning can also be involved in the development of phobias. Some people learn to be phobic of certain objects or situations by observing the fearful reactions of someone else who acts as a model in the situation. The child who observes a parent react with sheer panic to the sight of a spider or mouse may imitate the same behavioral response. People can also develop phobias from observing vivid media accounts of disasters, as when some people become afraid to fly after watching graphic TV coverage of a plane crash.

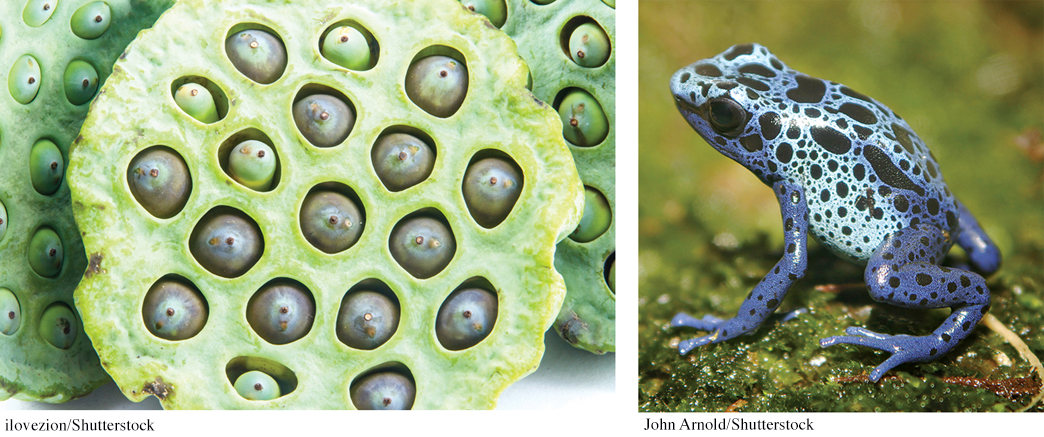

We also noted in Chapter 5 that humans seem biologically prepared to acquire fears of certain animals or situations, such as snakes or heights, which were survival threats in human evolutionary history (Workman & Reader, 2008).

People also seem to be predisposed to develop phobias toward creatures that arouse disgust, like slugs, maggots, or cockroaches. Instinctively, it seems, many people find such creatures repulsive, possibly because they are associated with disease, infection, or filth. Such phobias may reflect a fear of contamination or infection that is also based on human evolutionary history (Cisler & others, 2007).

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

ANXIETY AND INTRUSIVE THOUGHTS

KEY THEME

Extreme anxiety and intrusive thoughts are symptoms of both posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive–

KEY QUESTIONS

What is PTSD, and what causes it?

What is obsessive–

compulsive disorder? What are the most common types of obsessions and compulsions?

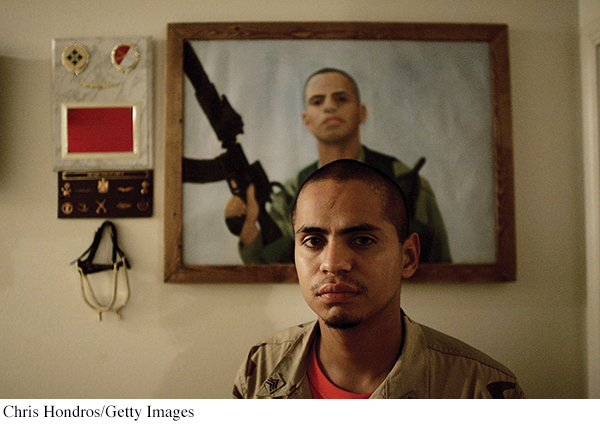

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a long-

Originally, PTSD was primarily associated with direct experiences of military combat. Veterans of military conflict in Afghanistan and Iraq, like veterans of earlier wars, have a higher prevalence of PTSD than nonveterans (E. Cohen & others, 2011; Fontana & Rosenheck, 2008). However, it’s now known that PTSD can also develop in survivors of other sorts of extreme traumas, such as natural disasters, physical or sexual assault, or terrorist attacks (McNally, 2003). Rescue workers, relief workers, and emergency service personnel can also develop PTSD symptoms (Berger & others, 2012; Eriksson & others, 2001). Simply witnessing the injury or death of others can be sufficiently traumatic for PTSD to occur. And some researchers have documented PTSD symptoms in people who were exposed to trauma in the media, such as graphic images related to terrorism or war on television (Garfin & others, 2015; Silver & others, 2013).

In any given year, it’s estimated that more than 5 million American adults experience PTSD. There is also a significant gender difference—

Four core clusters of symptoms characterize PTSD (DSM-

Posttraumatic stress disorder is somewhat unusual in that the source of the disorder is the traumatic event itself, rather than a cause that lies within the individual. Even well-

Terrorist attacks, because of their suddenness and intensity, are particularly likely to produce posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors, rescue workers, and observers (Neria & others, 2011). For example, four years after the bombing of the Murrah Building in Oklahoma City, more than a third of the survivors suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder (North & others, 1999). Seven years after the bombing, more than a quarter still had PTSD (North & others, 2011). Similarly, five years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, more than 11 percent of rescue and recovery workers met formal criteria for PTSD—

However, it’s also important to note that no stressor, no matter how extreme, produces posttraumatic stress disorder in everyone. Why is it that some people develop PTSD while others don’t? Several factors influence the likelihood of developing posttraumatic stress disorder. First, there is evidence that a vulnerability to PTSD can be inherited (Wilker & Kolassa, 2013). Second, people with a personal or family history of psychological disorders are more likely to develop PTSD when exposed to an extreme trauma (Amstadter & others, 2009; Koenen & others, 2008). Third, the magnitude of the trauma plays an important role. More extreme stressors are more likely to produce PTSD. Frequency of exposure is a factor as well. When people undergo multiple traumas, the incidence of PTSD can be quite high. One study even observed PTSD symptoms among journalists who never left the newsroom but were frequently exposed to traumatic images (Feinstein & others, 2014).

OBSESSIVE–

CHECKING IT AGAIN . . . AND AGAIN

MYTH SCIENCE

Is is true that people who are perfectionists probably have obsessive–

When you leave your home, you probably check to make sure all the doors are locked. You may even double-

Here’s a sense of what OCD is really like. Imagine you’ve checked the door 30 times. Yet you’re still not quite sure that the door is really locked. You know the feeling is irrational, but you feel compelled to check again and again. Imagine you’ve also had to repeatedly check that the coffeepot was unplugged, that the stove was turned off, and so forth. Finally, imagine that you got only two blocks away from home before you felt compelled to turn back and check again—because you still were not certain.

Sound agonizing? This is the psychological world of the person who suffers from one form of obsessive–

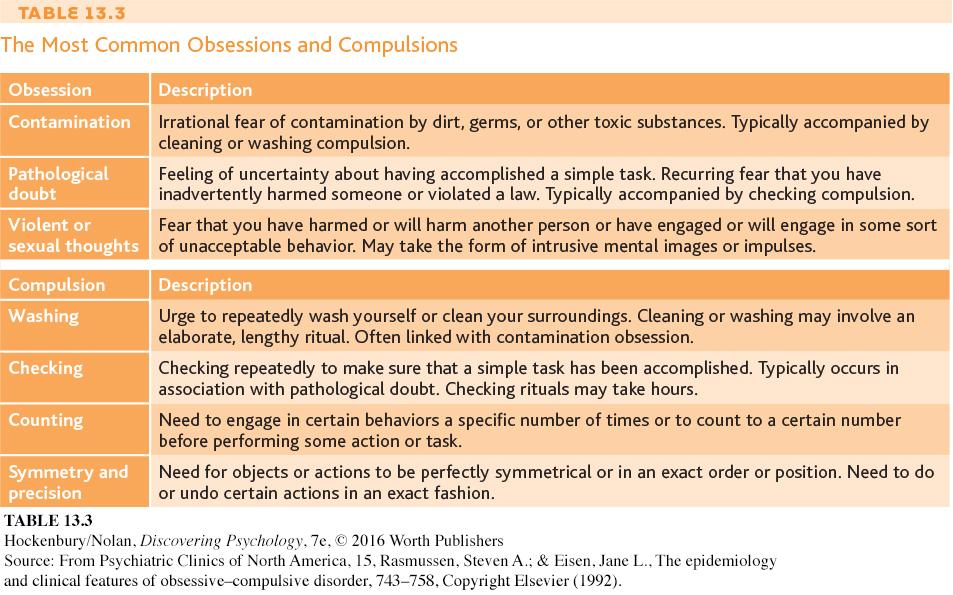

Obsessions are repeated, intrusive, uncontrollable thoughts or mental images that cause the person great anxiety and distress. Obsessions are not the same as everyday worries. Normal worries typically have some sort of factual basis, even if they’re somewhat exaggerated. In contrast, obsessions have little or no basis in reality and are often extremely far-

A compulsion is a repetitive behavior that a person feels driven to perform. Typically, compulsions are ritual behaviors that must be carried out in a certain pattern or sequence. Compulsions may be overt physical behaviors, such as repeatedly washing your hands, checking doors or windows, or entering and reentering a doorway until you walk through exactly in the middle. Or they may be covert mental behaviors, such as counting or reciting certain phrases to yourself. But note that the person does not compulsively wash his hands because he enjoys being clean. Rather, he washes his hands because to not do so causes extreme anxiety. If the person tries to resist performing the ritual, unbearable tension, anxiety, and distress result (Mathews, 2009).

Obsessions and compulsions tend to fall into a limited number of categories. About three-

Many people with obsessive–

People may experience either obsessions or compulsions. More commonly, obsessions and compulsions are both present. Often, the obsessions and compulsions are linked in some way. For example, a man who was obsessed with the idea that he might have lost an important document felt compelled to pick up every scrap of paper he saw on the street and in other public places.

Other compulsions bear little logical relationship to the feared consequences. For instance, a woman believed that if she didn’t get dressed according to a strict pattern, her husband would die in an automobile accident. In all cases, people with obsessive–

Interestingly, obsessions and compulsions take a similar shape in different cultures around the world. However, the content of the obsessions and compulsions tends to mirror the particular culture’s concerns and beliefs. In the United States, compulsive washers are typically preoccupied with obsessional fears of germs and infection. But in rural Nigeria and rural India, compulsive washers are more likely to have obsessional concerns about religious purity rather than germs (Rapoport, 1989; Rego, 2009).

EXPLAINING OBSESSIVE–

Although the causes of obsessive–

In addition, obsessive–

The anxiety, posttraumatic stress, and obsessive–

Test your understanding of Anxiety Disorders with  .

.