Depressive and Bipolar Disorders

DISORDERED MOODS AND EMOTIONS

KEY THEME

In the depressive and the bipolar disorders, disturbed emotions cause psychological distress and impair daily functioning.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the symptoms and course of major depressive disorder, persistent depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and cyclothymic disorder?

How prevalent are depressive and bipolar disorders?

What factors contribute to the development of depressive and bipolar disorders?

Let’s face it, we all have our ups and downs. When things are going well, we feel cheerful and optimistic. When events take a more negative turn, our mood can sour. We feel miserable and pessimistic. Either way, the intensity and duration of our moods are usually in proportion to the events going on in our lives. That’s completely normal.

In the depressive disorders and the bipolar and related disorders, however, emotions violate the criteria of normal moods. In quality, intensity, and duration, a person’s emotional state does not seem to reflect what’s going on in his or her life. A person may feel a pervasive sadness despite the best of circumstances. Or a person may be extremely energetic and overconfident with no apparent justification. These mood changes persist much longer than the normal fluctuations in moods that we all experience.

Because disturbed moods and emotions are core symptoms in both the depressive and bipolar disorders, they are sometimes called mood disorders or affective disorders. The word “affect” is synonymous with “emotion” or “feelings.” In DSM-

Major Depressive Disorder

MORE THAN ORDINARY SADNESS

The intense psychological pain of major depressive disorder is hard to convey to those who have never experienced it. Several patients described their struggles with depression to researchers (Smith & Rhodes, 2015). Ravi explained, “You get into a state I think mentally where, you’re just like out on an island. And . . . you can see from that island another shore and all these people are there, but there’s no way that you can get across.” Sally described it as “like part of you gone, your heart. . . . Perhaps half my heart has gone away.”

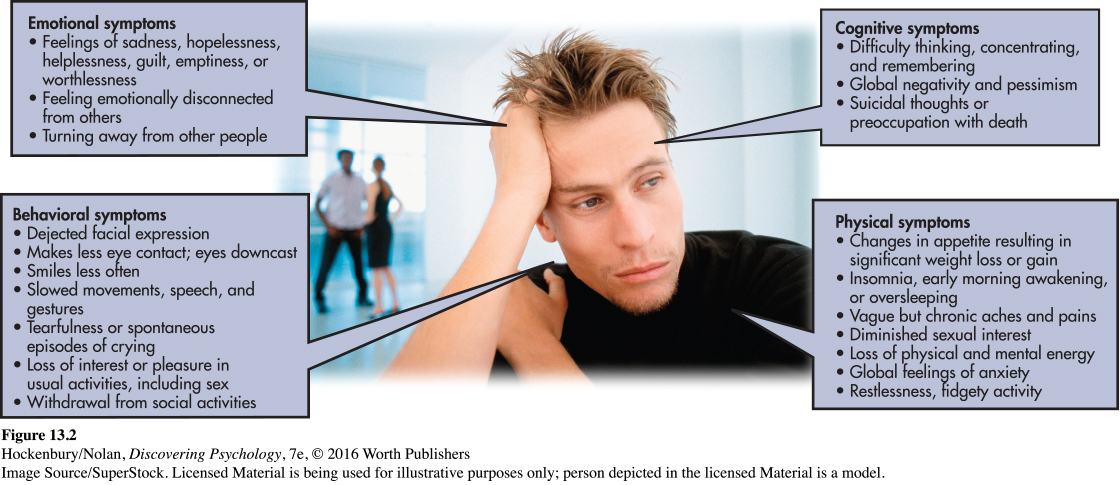

THE SYMPTOMS OF MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER

The patient quotes above give you a feeling for how the symptoms of depression affect the whole person—

Suicide is always a potential risk in major depressive disorder (Brådvik & Berglund, 2010). Thoughts become globally pessimistic and negative about the self, the world, and the future (Beck & others, 1979; Possel & Winkeljohn Black, 2014). This pervasive negativity and pessimism are often manifested in suicidal thoughts or a preoccupation with death. Approximately 10 percent of those suffering from major depressive disorder attempt suicide (McGirr & others, 2007). Grammy award–

Abnormal sleep patterns are another hallmark of major depressive disorder. The amount of time spent in nondreaming, deeply relaxed sleep is greatly reduced or absent (see Chapter 4). Rather than the usual 90-

To be diagnosed with major depressive disorder, a person must display most of the symptoms described for two weeks or longer (DSM-

One significant negative event deserves special mention: the death of a loved one. Previous editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual stated that depression-

Although major depressive disorder can occur at any time, some people experience symptoms that intensify at certain times of the year. For people with seasonal affective disorder (SAD), repeated episodes of major depressive disorder are as predictable as the changing seasons, especially the onset of autumn and winter when there is the least amount of sunlight. Seasonal affective disorder is more common among women and among people who live in the northern latitudes (Partonen & Pandi-

Some people experience a chronic form of depression called persistent depressive disorder that is often less severe than major depressive disorder. Persistent depressive disorder may develop after some stressful event or trauma, such as the death of a parent in childhood (DSM-

THE PREVALENCE AND COURSE OF MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER

Major depressive disorder is often called “the common cold” of psychological disorders, and for good reason: It is among the most prevalent psychological disorders. And in terms of its physical, psychological, and economic impact, it’s one of the most devastating of any illness worldwide (Ledford, 2014). In any given year, about 7 percent of Americans are affected by major depressive disorder (Kessler & others, 2005b). In terms of lifetime prevalence, many researchers have estimated that about 15 percent of Americans will be affected by major depressive disorder at some point in their lives. However, some researchers suspect that number is too low. In a longitudinal study following more than 800 people for 30 years—

Women are about twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with major depressive disorder (Hyde & others, 2008). Why the striking gender difference in the prevalence of major depressive disorder? Research by psychologist Susan Nolen-

There also are cultural differences related to major depressive disorder. Although depression occurs globally with similar symptom presentation across different countries, people often talk about it differently (Ferrari & others, 2013; Simon & others, 2002). For example, people in Cambodia refer to their experience with depression as “the water in my heart has fallen” (Singh, 2015). And the Haitian word for depression translates to “thinking too much” (Singh, 2015). Such differences in the language and understanding of depression must be taken into account when diagnosing and treating this disorder.

Many people who experience major depressive disorder try to cope with the symptoms without seeking professional help (Edlund & others, 2008; Farmer & others, 2012). Left untreated, the symptoms of major depressive disorder can easily last six months or longer. When not treated, depression may become a recurring mental disorder that becomes progressively more severe. More than half of all people who have been through one episode of major depressive disorder can expect a relapse, usually within two years. With each recurrence, the symptoms tend to increase in severity and the time between major depressive episodes decreases (Hammen, 2005; Roca & others, 2011). However, it’s important to note that several effective treatments for depression are available. We will describe many of these treatments in Chapter 14.

Bipolar Disorder

AN EMOTIONAL ROLLER COASTER

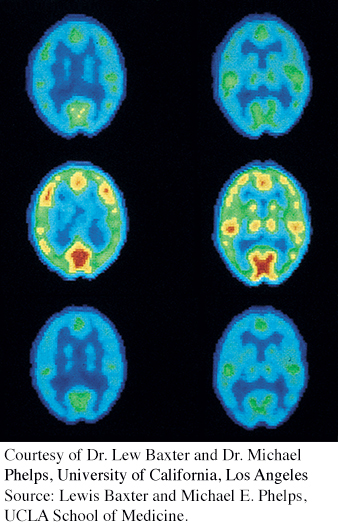

Source: Lewis Baxter and Michael E. Phelps, UCLA School of Medicine.

Years ago, your author Susan worked as a therapist in a community mental health center. She had been treating a client, a man in his fifties named Henry, who was experiencing symptoms of depression. After several months of appointments, he failed to show up for two weekly appointments in a row. When he returned, he was buoyant. He walked quickly with a bounce to his step, and greeted everyone in the waiting room and at the front desk as if they were old friends. Henry entered Susan’s office grinning, his eyes wild.

Henry’s new mood was not just a decrease in his symptoms of depression. It was a swing in the opposite direction. Henry excitedly told Susan that he had quit his job as an engineer at a small radio station and was putting his savings into an investment scheme that involved medical equipment. He soon changed topics. “I won’t be here next week because I’m going to Mexico! I’m staying at a famous resort in Tulum!” He explained that he would connect with Hollywood stars there, and would soon be working on a movie project, maybe as a producer.

Henry spoke loudly and so rapidly that his words often got tangled up with each other. His arms and legs looked as if they were about to get tangled up, too—

THE SYMPTOMS OF BIPOLAR DISORDER

Henry displayed classic symptoms of the mental disorder that used to be called manic depression and is today called bipolar disorder. In contrast to major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder almost always involves abnormal moods at both ends of the emotional spectrum. Episodes of incapacitating depression alternate with shorter periods of extreme euphoria, called manic episodes. For the vast majority of people with bipolar disorder, a manic episode immediately precedes or follows a bout with major depressive disorder. However, a small percentage of people with bipolar disorder experience only manic episodes (DSM-

Many people use the term “manic” informally to describe people who are in a more energetic mood than normal. But a true manic episode is much more extreme than what we often mean in casual conversation. Manic episodes typically begin suddenly, and symptoms escalate rapidly. During a manic episode, people are uncharacteristically euphoric, expansive, and excited for several days or longer. Although they sleep very little, they have boundless energy. The person’s self-

Henry’s fast-

Not surprisingly, the ability to function during a manic episode is severely impaired. Hospitalization is usually required, partly to protect people from the potential consequences of their inappropriate decisions and behaviors. During manic episodes, people can also run up a mountain of bills, disappear for weeks at a time, become sexually promiscuous, or commit illegal acts. Very commonly, the person becomes agitated or verbally abusive when others question her grandiose claims (Miklowitz & Johnson, 2007).

Some people experience a milder but chronic form of bipolar disorder called cyclothymic disorder. In cyclothymic disorder, people experience moderate but frequent mood swings for two years or longer. These mood swings are not severe enough to qualify as either bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder. Often, people with cyclothymic disorder are perceived as being extremely moody, unpredictable, and inconsistent.

THE PREVALENCE AND COURSE OF BIPOLAR DISORDER

As in Henry’s case, the onset of bipolar disorder typically occurs in the person’s early 20s. The extreme mood swings of bipolar disorder tend to start and stop much more abruptly than the mood changes of major depressive disorder. And while an episode of major depression can easily last for six months or longer, the manic and depressive episodes of bipolar disorder tend to be much shorter—

Bipolar disorder is far less common than major depressive disorder. Unlike major depressive disorder, there are no differences between the sexes in the rate at which bipolar disorder occurs. For both men and women, the lifetime risk of developing bipolar disorder is about 1 percent (Merikangas & others, 2007). Bipolar disorder is rarely diagnosed in childhood.

In the vast majority of cases, bipolar disorder is a recurring mental disorder (Jones & Tarrier, 2005). A small percentage of people with bipolar disorder display rapid cycling, experiencing four or more manic or depressive episodes every year (Marneros Goodwin, 2005). More commonly, bipolar disorder tends to recur every couple of years. Often, bipolar disorder recurs when the individual stops taking lithium, a medication that helps control the disorder. Susan later learned that this was what had happened with Henry.

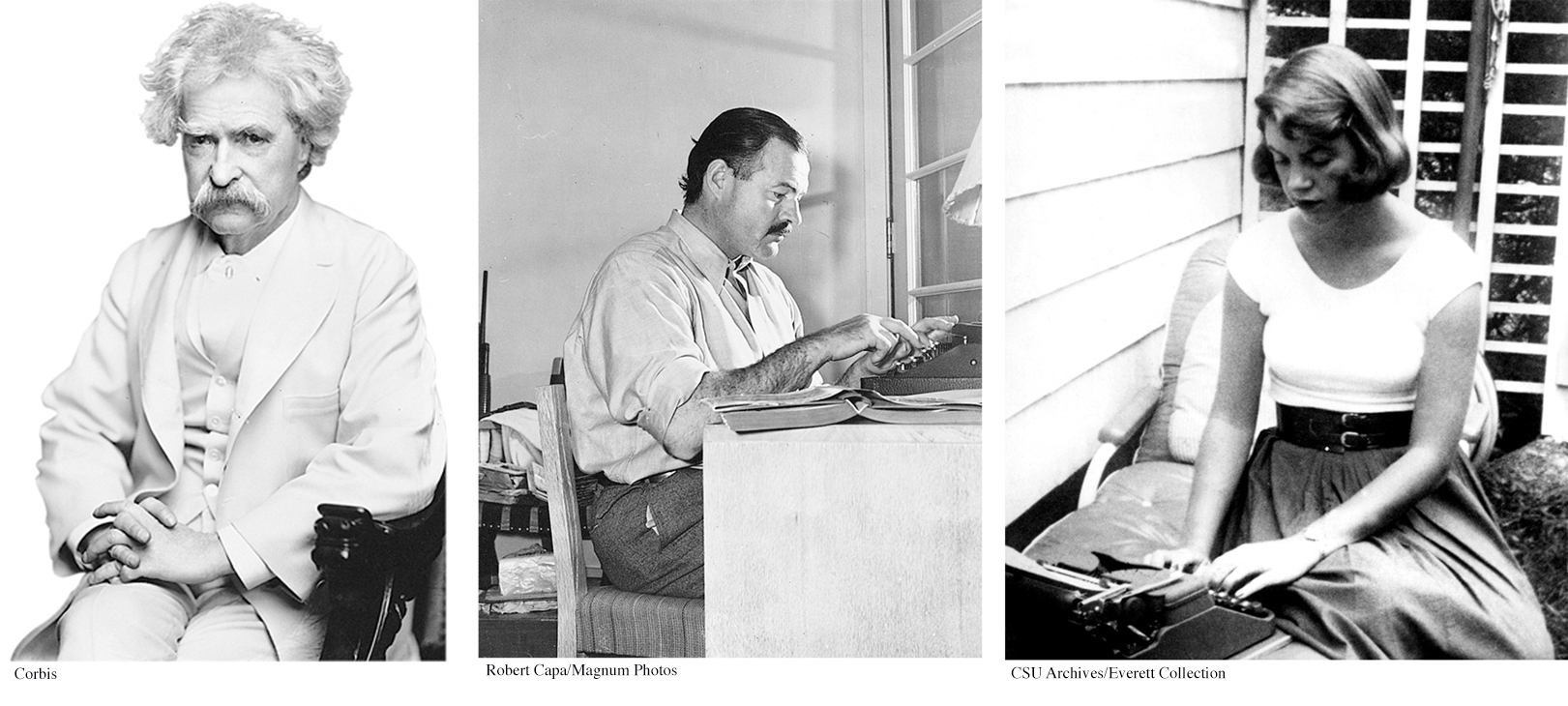

Explaining Depressive Disorders and Bipolar Disorders

Multiple factors appear to be involved in the development of depressive and bipolar disorders. First, family, twin, and adoption studies suggest that some people inherit a genetic predisposition, or a greater vulnerability, to depressive and bipolar disorders (Kendler & others, 2006; Levinson, 2009; Smoller & Finn, 2003). Researchers have consistently found that both major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder, like most psychological disorders, tend to run in families, although bipolar disorder has much stronger genetic roots than major depressive disorder (Moore & others, 2013; Sullivan & others, 2012). Personality characteristics associated with these disorders have also been found to have a genetic component, even in children who do not share a parent’s diagnosis (Murray & others, 2007). For example, nondepressed children of parents with depressive disorders show the kind of biased thinking and the patterns of brain activity often seen in people who are depressed (Gotlib & others, 2014).

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that many psychological disorders run in families?

A second factor that has been implicated in the development of depressive and bipolar disorders is differences in the activation of structures in the brain. For example, one study found that people who were depressed showed increased activation in certain parts of the brain when trying to get rid of negative words in their working memory (Foland-

Another important factor is disruptions in brain chemistry. Since the 1960s, several medications, called antidepressants, have been developed to treat major depressive disorder. Some researchers believe that increased levels in the brain of some neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine and serotonin, accompany an improvement in the symptoms of depression among people taking antidepressants. Antidepressant medications will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 14.

Abnormal levels of another neurotransmitter may also be involved in bipolar disorder. For decades, it’s been known that the drug lithium effectively alleviates symptoms of both mania and depression. Apparently, lithium regulates the availability of a neurotransmitter called glutamate, which acts as an excitatory neurotransmitter in many brain areas (Dixon & Hokin, 1998). By normalizing glutamate levels, lithium helps prevent both the excesses that may cause mania and the deficits that may cause depression.

Stress is also implicated in the development of depressive and bipolar disorders (Quinn & Joormann, 2015). First, major depressive disorder and chronic stress lead to remarkably similar changes in the neurochemistry of the brain (Hill & others, 2012). Second, major depressive disorder is often triggered by traumatic and stressful events (Gutman & Nemeroff, 2011). Exposure to recent stressful events is one of the best predictors of episodes of major depressive disorder. This is especially true for people who have experienced previous episodes of depression and who have a family history of depressive disorders or mood disorders. And this is especially true for exposure to stress in relationships with other people (Vrshek-

Finally, research has uncovered some intriguing links between cigarette smoking and the development of major depressive disorder and other psychological disorders (Munafo & others, 2008). We explore the connection between cigarette smoking and mental illness in the Critical Thinking box “Does Smoking Cause Major Depressive Disorder and Other Psychological Disorders?”

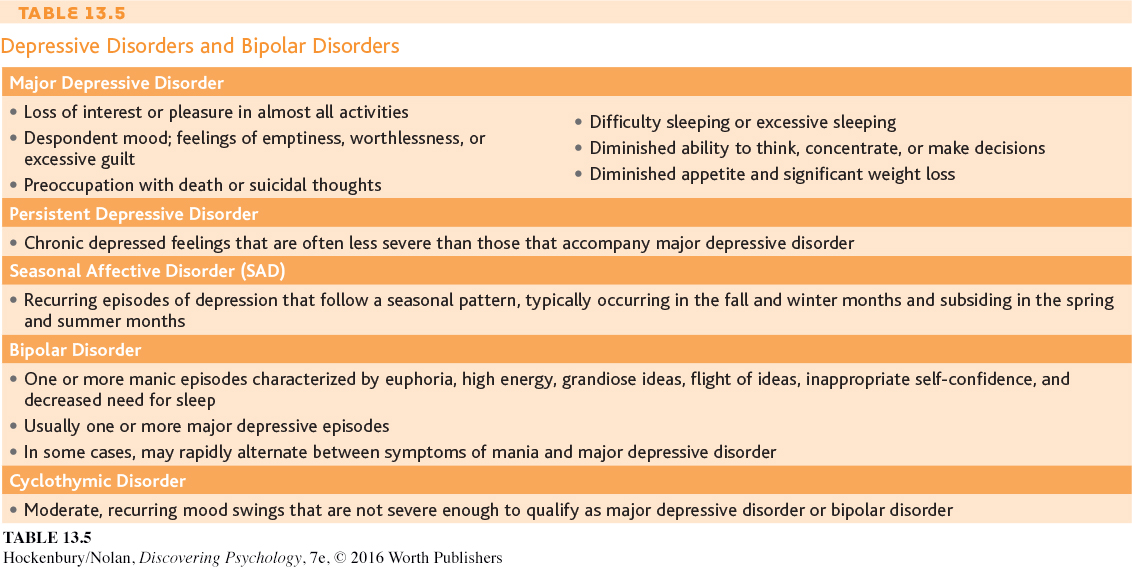

In summary, considerable evidence points to the role of genetic factors, biochemical factors, and stressful life events in the development of both depressive disorders and bipolar disorders (Feliciano & Areàn, 2007). However, exactly how these factors interact to cause these disorders is still being investigated. Table 13.5 summarizes the symptoms of the most important depressive disorders and bipolar disorders.

CRITICAL THINKING

Does Smoking Cause Major Depressive Disorder and Other Psychological Disorders?

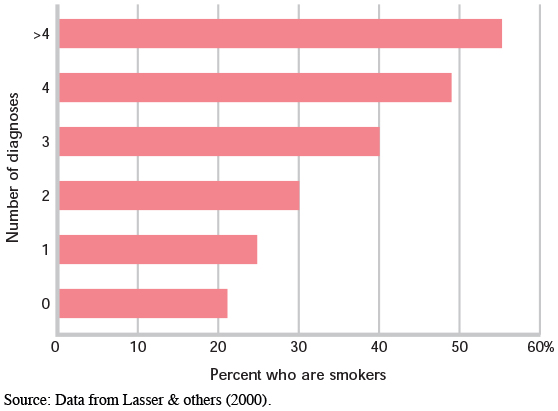

Are people with a mental disorder more likely to smoke than other people? Researcher Karen Lasser and her colleagues (2000) assessed smoking rates in American adults with and without psychological disorders. Lasser found that people with mental illness are twice as likely to smoke cigarettes as people with no mental illness. Here are some of the specific findings from Lasser’s study:

Forty-

one percent of individuals with a current psychological disorder are smokers, as compared to 22 percent of people who have never been diagnosed with a mental disorder. People with a psychological disorder are more likely to be heavy smokers, consuming a pack of cigarettes per day or more.

People who have been diagnosed with many psychological disorders have higher rates of smoking than people with fewer mental disorders (see the graph below).

What can account for the correlation between smoking and psychological disorders? Subjectively, smokers often report that they experience better attention and concentration, increased energy, lower anxiety, and greater calm after smoking, effects that are probably due to the nicotine in tobacco. So, one possibl explanation is that people a mental illness smoke as of self-

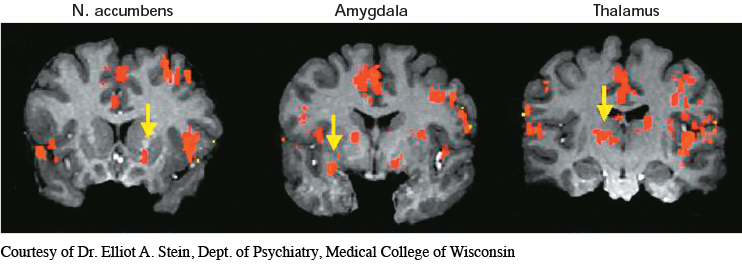

Nicotine, of course, is a powerful psychoactive drug. It triggers the release of dopamine and stimulates key brain structures involved in producing rewarding sensations, including the thalamus, the amygdala, and the nucleus accumbens (Berrendero & others, 2010; Le Foll & Goldberg, 2007; Stein & others, 1998). Nicotine receptors on different neurons also regulate the release of other important neurotransmitters, including serotonin, acetylcholine, GABA, and glutamate (McGehee & others, 2007). In other words, nicotine affects multiple brain structures and alters the release of many different neurotransmitters. These same brain areas and neurotransmitters are also directly involved in many different psychological disorders.

Although the idea that mental illness causes smoking seems to make sense, some researchers now believe that the arrow of causation points in the opposite direction. In the past decade, many studies have suggested that smoking triggers the onset of symptoms in people who are probably already vulnerable to the development of a mental disorder, especially major depressive disorder. Consider just a few studies:

Several studies focusing on adolescents found that cigarette smoking predicted the onset of depressive symptoms, rather than the other way around (Beal & others, 2013; Boden & others, 2010; Windle & Windle, 2001).

In studies of people with bipolar disorder, daily cigarette smokers had worse symptoms and lengthier hospitalizations than nonsmoking patients with bipolar disorder (Dodd & others, 2010; Saiyad & El-

Mallakh, 2012). A positive association was found between smoking and the severity of symptoms experienced by people with anxiety disorders (McCabe & others, 2004).

In a study of people with schizophrenia, 90 percent started smoking before their illness began (Kelly & McCreadie, 1999). In addition, among adolescent boys, smokers were almost twice as likely as nonsmokers to later develop schizophrenia (Weiser & others, 2004). These studies suggest that smoking may precipitate an initial schizophrenic episode in vulnerable people.

Further research may help disentangle the complex interaction between smoking and mental disorders, but one fact is known: Mentally ill cigarette smokers, like other smokers, are at much greater risk of premature disability and death. So, along with the psychological and personal suffering that accompanies almost all psychological disorders, those with mental illness carry the additional burden of consuming nearly half of all the cigarettes smoked in the United States.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

Is the evidence sufficient to conclude that there is a causal relationship between cigarette smoking and the onset of mental illness symptoms? Why or why not?

Should tobacco companies be required to contribute part of their profits to the cost of mental health treatment and research?