Eating Disorders

ANOREXIA, BULIMIA, AND BINGE-EATING DISORDER

Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder are psychological disorders characterized by severely disturbed, maladaptive eating behaviors.

What are the symptoms, characteristics, and causes of anorexia nervosa?

What are the symptoms, characteristics, and causes of bulimia nervosa?

What are the symptoms, characteristics, and causes of binge-eating disorder?

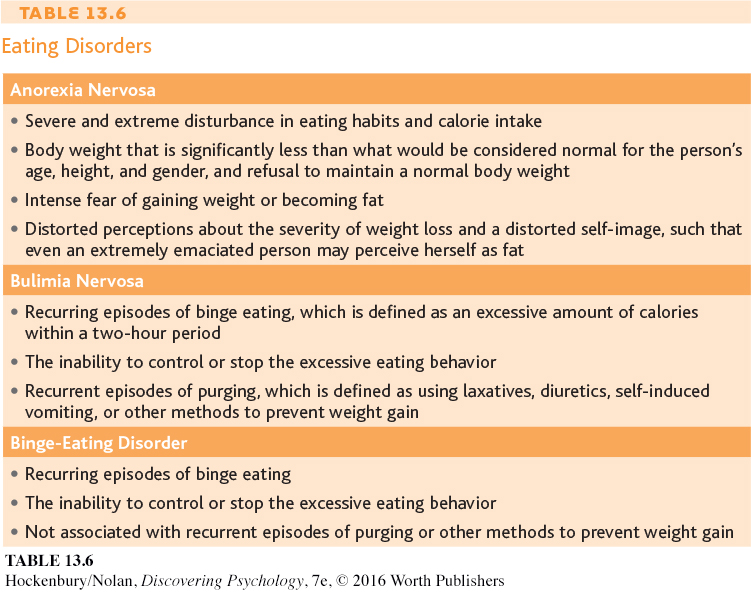

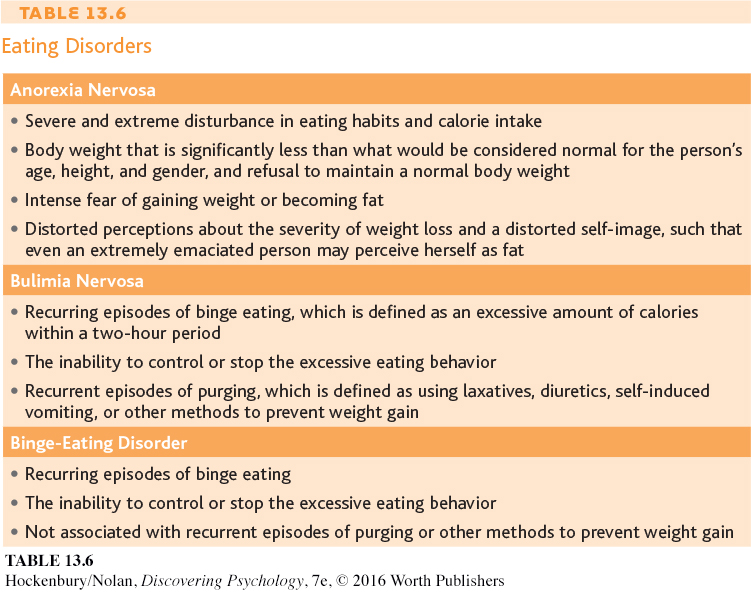

Eating disorders involve serious and maladaptive disturbances in eating behavior. The DSM-5 category in which eating disorders are included is technically called “Eating and Feeding Disorders,” which includes disorders of infancy and childhood. But here we will focus on disorders that tend to begin in adolescence or early adulthood. Eating disorders can include extreme reduction of food intake, severe bouts of overeating, and obsessive concerns about body shape or weight (DSM-5, 2013). The three main types of eating disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder, which usually begin during adolescence or early adulthood (see Table 13.6). Ninety to 95 percent of the people who experience an eating disorder are female (Støving & others, 2011). Despite the 10-to-1 gender-difference ratio, the central features of eating disorders are similar for males and females.

Hear the story of one man’s struggle with an eating disorder. Watch Video Activity: Overcoming Anorexia Nervosa.

Video material is provided by BBC

Worldwide Learning and CBS News

Archives and produced by Princeton Academic Resources

LIFE-THREATENING WEIGHT LOSS

Three key features define anorexia nervosa. First, the person refuses to maintain a minimally normal body weight. With a body weight that is significantly below normal, body mass index can drop to 12 or lower. Second, despite being dangerously underweight, the person with anorexia is intensely afraid of gaining weight or becoming fat. Third, she has a distorted perception about the size of her body. Although emaciated, she looks in the mirror and sees herself as fat or obese, denying the seriousness of her weight loss (DSM-5, 2013).

Page 559

The severe malnutrition caused by anorexia disrupts body chemistry in ways that are very similar to those caused by starvation. Basal metabolic rate decreases, as do blood levels of glucose, insulin, and leptin. Other hormonal levels drop, including the level of reproductive hormones. In women, reduced estrogen may result in the menstrual cycle stopping. In males, decreased testosterone disrupts sex drive and sexual function (Pinheiro & others, 2010). Because the ability to retain body heat is greatly diminished, people with severe anorexia often develop a soft, fine body hair called lanugo.

BULIMIA NERVOSA AND BINGE-EATING DISORDER

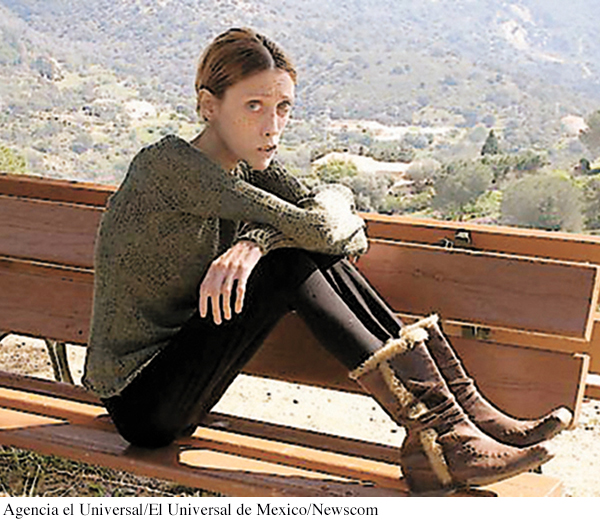

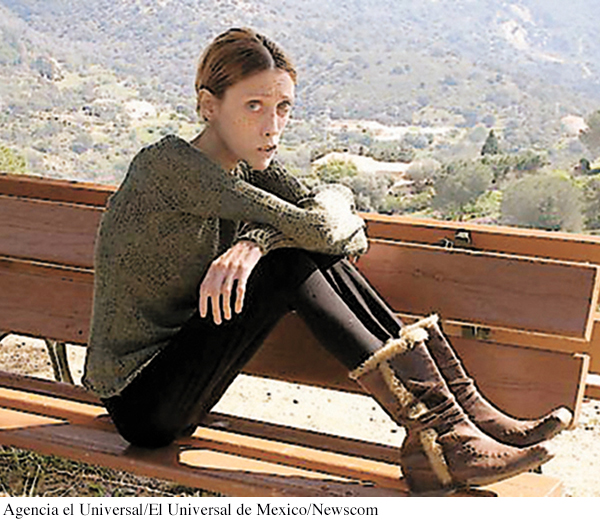

Size 0: An Impossible Cultural Ideal? Isabelle Caro, a famous French fashion model, died in 2010 after a decade-long struggle with anorexia. After the anorexia-related deaths of Caro and a Brazilian model, Ana Carolina Reston, France, Germany, and Spain proposed bans on ultra-thin models. But despite periodic outcries, the emaciated, skin-and-bones look continues to be the fashion industry norm. Eating disorders are most prevalent in developed, Western countries, where a slender body is the cultural ideal, especially for women and girls. Many psychologists believe that such unrealistic body expectations contribute to eating disorders (Hawkins & others, 2004; Treasure & others, 2008).

Agencia el Universal/El Universal de Mexico/Newscom

Like people with anorexia, people with bulimia nervosa fear gaining weight. Intense preoccupation and dissatisfaction with their bodies are also apparent. However, people with bulimia stay within a normal weight range or may even be slightly overweight. Another difference is that people with bulimia usually recognize that they have an eating disorder.

People with bulimia nervosa experience extreme periods of binge eating, consuming as many as 50,000 calories on a single binge. Binges typically occur twice a week and are often triggered by negative feelings or hunger. During the binge, the person usually consumes sweet, high-calorie foods that can be swallowed quickly, such as ice cream, cake, and candy. Binges typically occur in secrecy, leaving the person feeling ashamed, guilty, and disgusted by his own behavior. After bingeing, he compensates by purging himself of the excessive food by self-induced vomiting or by misuse of laxatives or enemas. Once he purges, he often feels psychologically relieved. Some people with bulimia don’t purge themselves of the excess food. Rather, they use fasting and excessive exercise to keep their body weight within the normal range (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; DSM-5, 2013).

Like anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa can take a serious physical toll on the body. Repeated purging disrupts the body’s electrolyte balance, leading to muscle cramps, irregular heartbeat, and other cardiac problems, some potentially fatal. Stomach acids from self-induced vomiting erode tooth enamel, causing tooth decay and gum disease. Over time, frequent vomiting can damage the gastrointestinal tract (Powers, 2009).

Like people with bulimia, people with binge-eating disorder engage in bingeing behaviors (DSM-5, 2013). Unlike people with bulimia, they do not engage in purging or other behaviors that rid their bodies of the excess food. People with binge-eating disorder experience the same feelings of distress, lack of control, and shame that people with bulimia experience.

Page 560

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

At several points in this chapter, we’ve noted ways in which culture shapes the symptoms of psychological disorders. Psychological disorders do not always look the same in every culture. And further, some disorders, called culture-specific disorders or culture-bound syndromes, appear to be found only in a single culture.

Shutting Themselves In Nineteen-year-old Dai Hasebe has lived as a hikikomori or shut-in since he was 11 years old, rarely leaving his family’s Tokyo apartment. Like other hikikomori, he does not attend school or hold a job. Although hikikomori has some features in common with social anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder, the specific constellation of symptoms appears to be unique to Japanese culture.

Stuart Isett/Polaris Images

For example, hikikomori is a syndrome first identified in Japan in the 1970s in adolescents and young adults (Kato & others, 2011; Teo, 2010). Hikikomori involves a pattern of extreme social withdrawal. People suffering from hikikomori become virtual recluses, often confining themselves to a single room in their parents’ home, sometimes for years. They refuse all social interaction or engagement with the outside world and, in some cases, do not speak even to family members who care for them. Locked away from the world, they spend their time alone in their room, preoccupied with watching television, playing video games, or surfing the Internet.

Most hikikomori are young males, but the syndrome has also been identified in women and middle-aged adults (Kato & others, 2012). Once rare, hikikomori has become a social phenomenon. Some estimates are that a million or more young Japanese live as hikikomori (Watts, 2002).

Is it true that the types of psychological disorders are pretty much the same in every culture?

Hikikomori has symptoms in common with several Western disorders, including social anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and agoraphobia. However, its specific features are uniquely Japanese, reflecting social pressures and values. Some researchers believe that hikikomori is an extreme reaction to the pressure to succeed in school and to conform to social expectations that characterizes Japanese culture (Teo, 2010; Teo & Gaw, 2010). Also implicated is the close, almost symbiotic relationship that is encouraged between mothers and children, especially sons, in Japan. Japanese parents, apparently, are more tolerant of the hikikomori’s continuing dependency into adulthood than parents in other cultures might be (Wong & Ying, 2006).

Western cultures have culture-bound syndromes, too. Consider the case of anorexia nervosa, discussed on pages 558–559. Isolated cases of self-starvation have been reported throughout history and in many cultures. For the most part, though, these cases of anorexia nervosa were rare and seem to have been associated with religious motives or a desire for spiritual purification (Banks, 2009; Keel & Klump, 2003).

The most common form of anorexia nervosa today has a distinctly different look. Its incidence is highest in the United States, Western Europe, and other “westernized” cultures, where an unnaturally slender physique is the cultural ideal (Anderson-Fye, 2009). In these cultures, self-starvation is associated with an intense fear of becoming fat (DSM-5, 2013). There is also a much higher incidence in women than in men, reflecting cultural beliefs about the importance of thinness for women (Keel & Klump, 2003).

Interestingly, researchers are seeing that the global transmission of social trends and information about psychological disorders appear to be contributing to the spread of syndromes that were once limited to a particular culture. For example, Chinese psychiatrist Sing Lee only learned about eating disorders during his training in the United Kingdom in the 1980s. Upon his return home to Hong Kong, he combed through hospital records and interviewed colleagues but could find very few occurrences of anorexia nervosa or other eating disorders in his native country. And, these few cases looked remarkably different from what he had observed in the United Kingdom. In Hong Kong, young women with anorexia did not express a fear of being fat. Instead they attributed their extreme thinness to physical problems such as a bloated stomach or a poor appetite (Lee & others, 1993). Also, unlike patients in the West, Hong Kong patients tended to be from less privileged backgrounds and were less likely to follow fashion and beauty trends.

But that all changed in 1994, when fourteen-year-old school-girl Charlene Hsu Chi-Ying, emaciated and weighing only 75 pounds, collapsed and died on a busy street in the heart of Hong Kong (Watters, 2010). The dramatic nature of her death led to breathless media coverage. “Girl Who Died in Street Was a Walking Skeleton” read one headline. Within hours, many people in Hong Kong read about anorexia nervosa for the first time. With no traditional framework for understanding why an honor student would deliberately starve herself to death, the Hong Kong media sought out Western explanations, blaming images of women in the media and the fashion industry. Soon, celebrities were announcing their own battles with anorexia, and reports of anorexia became increasingly common. Over the next decade, eating disorders in Hong Kong, Japan, and other Asian countries skyrocketed, and patients were much more likely to report a fear of being fat (S. Lee & others, 2010; Pike & Borovoy, 2004).

Slimming—A Global Pursuit? Taiwanese pop star Jolin Tsai is widely admired for her singing talent—and for her slender build. The author of a best-selling diet book, Tsai often shares her weight-loss secrets with interviewers. The incidence of eating disorders in many Asian countries has skyrocketed in recent decades. Some researchers attribute this increase to the spread of Western ideals of beauty along with publicity about anorexia nervosa, a disease previously rare in these countries (Watters, 2010). “Slimming” diets, clinics, and drugs are a growing industry across Asia.

TPG/Getty Images

Many questions about culture-bound syndromes remain unanswered. For example, it is not clear whether culture-bound syndromes like hikikomori are distinct disorders, or whether they represent a culturally influenced expression of some more universal underlying pathology. And when a disorder like anorexia nervosa appears to spread across cultures, is the increased incidence actually caused by media coverage? Or does it simply reflect an increase in the diagnosis of cases that already existed? These questions are complex and unlikely to have simple answers. As we’ve seen throughout this chapter, psychological disorders reflect the complex interaction of biological predispositions and psychological factors and are always expressed within a particular social and cultural context. So, it’s unlikely that any single factor is responsible for the rate or symptoms of a particular psychological disorder.

CAUSES OF EATING DISORDERS

Anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder involve decreases in brain activity of the neurotransmitter serotonin (Bailer & Kaye, 2011; Kuikka & others, 2001). Disrupted brain chemistry may also contribute to the fact that eating disorders frequently co-occur with other psychiatric disorders, such as major depressive disorder, substance abuse disorder, personality disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and anxiety disorders (Thompson & others, 2007; Swanson & others, 2011). While chemical imbalances may cause eating disorders, researchers are also studying whether they can result from eating disorders as well (Smolak, 2009).

Family interaction patterns may also contribute to eating disorders. For example, critical comments by parents or siblings about a child’s weight, or parental modeling of disordered eating, may increase the odds that an individual develops an eating disorder (Quiles Marcos & others, 2013; Thompson & others, 2007). There also is evidence that other psychological characteristics may be risk factors. For example, having negative beliefs about oneself is associated with having an eating disorder (Yiend & others, 2014). Also, researchers have found that a tendency toward perfectionism in childhood—traits like needing to complete schoolwork perfectly and feeling a need to obey rules without question—was associated with a later diagnosis of anorexia (Halmi & others, 2012). Girls actor Zosia Mamet explained that her experience with an eating disorder “. . . has never really been about weight or food—that’s just the way the monster manifests itself. Really these diseases are about control: control of your life and of your body” (Mamet, 2014).

Page 561

Although cases of eating disorders have been documented for at least 150 years, contemporary Western cultural attitudes toward thinness and dieting probably contribute to the increased incidence of eating disorders today. This seems to be especially true with anorexia, which occurs predominantly in Western or “westernized” countries (Anderson-Fye, 2009; Cafri & others, 2005). We discuss this issue and the more general topic of culture’s effects on psychological disorders in the Culture and Human Behavior box “Culture-Bound Syndromes.”

Test your understanding of Mood Disorders and Eating Disorders with  .

.

.

.