The Dissociative Disorders

FRAGMENTATION OF THE SELF

KEY THEME

In the dissociative disorders, disruptions in awareness, memory, and identity interfere with the ability to function in everyday life.

KEY QUESTIONS

What is dissociation, and how do normal dissociative experiences differ from the symptoms of dissociative disorders?

What are dissociative amnesia, dissociative amnesia with dissociative fugue, and dissociative identity disorder (DID)?

What is thought to cause DID?

Despite the many changes you’ve experienced throughout your lifetime, you have a pretty consistent sense of identity. You’re aware of your surroundings and can easily recall memories from the recent and distant past. In other words, a normal personality is one in which awareness, memory, and personal identity are associated and well integrated.

In contrast, a dissociative experience is one in which a person’s awareness, memory, and personal identity become separated or divided. While that may sound weird, dissociative experiences are not inherently pathological. Mild dissociative experiences are quite common and completely normal (Dalenberg & others, 2009; Wieland, 2011). For example, you become so absorbed in a book or movie that you lose all track of time. While driving, your author Susan is occasionally so preoccupied with her thoughts—

Clearly, then, dissociative experiences are not necessarily abnormal. But in the dissociative disorders, the dissociative experiences are much more extreme or more frequent and they severely disrupt everyday functioning. Awareness, or recognition of familiar surroundings, may be completely obstructed. Memories of pertinent personal information may be unavailable to consciousness. Identity may be lost, confused, or fragmented (Dell & O’Neil, 2009).

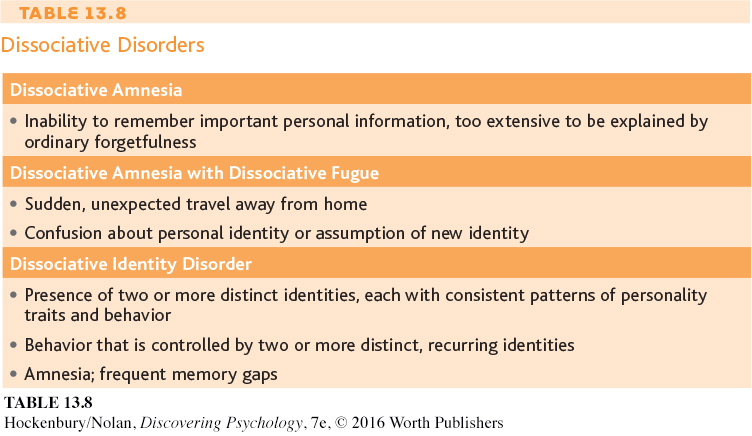

The category of dissociative disorders consists of two basic disorders: (1) dissociative amnesia, which can occur either with or without dissociative fugue, and (2) dissociative identity disorder, which was previously called multiple personality disorder. Until recently, the dissociative disorders were thought to be extremely rare. How rare? An extensive review conducted in the 1940s uncovered a grand total of 76 reported cases of dissociative disorders since the beginnings of modern medicine in the 1700s (Taylor & Martin, 1944). Although a few more cases were reported during the 1950s and 1960s, the clinical picture changed dramatically in the 1970s when a surge of dissociative disorder diagnoses occurred (Kihlstrom, 2005). Later in this discussion, we’ll explore some of the possible reasons as well as the controversy surrounding the “epidemic” of dissociative disorders that began in the 1970s.

Dissociative Amnesia and Dissociative Fugue

FORGETTING AND WANDERING

Dissociative amnesia refers to the partial or total inability to recall important information that is not due to a medical condition, such as an illness, an injury, or a drug. Usually the person develops amnesia for personal events and information, rather than for general knowledge or skills. That is, the person may not be able to remember his wife’s name but does remember how to read and who Martin Luther King, Jr., was. In most cases, dissociative amnesia is a response to stress, trauma, or an extremely distressing situation, such as combat, marital problems, or physical abuse (McLewin & Muller, 2006).

Some cases of dissociative amnesia involve a condition called dissociative fugue. In amnesia with dissociative fugue, the person outwardly appears completely normal. However, the person is confused about her identity. While in the fugue state, she suddenly and inexplicably travels away from her home, wandering to other cities or even countries. In some cases, people in a fugue state adopt a completely new identity.

As is true with other cases of amnesia, dissociative fugues are thought to be associated with traumatic events or stressful periods. However, it’s unclear as to how a fugue state develops, or why a person experiences a fugue state rather than other sorts of symptoms, such as simple anxiety or depression. Interestingly, when the person “awakens” from the fugue state, she may remember her past history but have amnesia for what occurred during the fugue state (DSM-

Dissociative Identity Disorder

MULTIPLE PERSONALITIES

Among the dissociative disorders, none is more fascinating—

Typically, each personality has her or his own name and is experienced as if it has her or his own personal history and self-

Symptoms of amnesia and memory problems are reported in virtually all cases of DID (Dorahy, 2014). There are frequent gaps in memory for both recent and childhood experiences. Commonly, those with dissociative identity disorder “lose time” and are unable to recall their behavior or whereabouts during specific time periods.

In addition to their memory problems, people with DID typically have numerous psychiatric and physical symptoms, along with a chaotic personal history (Cardena & Gleaves, 2007). Symptoms of major depressive disorder, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, sleep disorders, and self-

Not all mental health professionals are convinced that dissociative identity disorder is a genuine psychological disorder (Cardena & Gleaves, 2007; Lynn & others, 2006 a). One reason for skepticism is that reported cases sharply increased in the early 1970s shortly after books, films, and television dramas about multiple personality disorder became popular. As psychologist John Kihlstrom (2005) noted, not only the number of cases but also the number of “alters” showed a dramatic increase. To some psychologists, such findings suggest that patients with DID learned “how to behave like a multiple” from media portrayals of sensational cases or by responding to their therapists’ suggestions (Gee & others, 2003; Lynn & others, 2012). People with another mental illness or other vulnerability might be particularly susceptible to such influences (Lynn & others, 2012). And there is research to support this conclusion. Guy Boysen and Alexandra VanBergen reviewed many studies of people with dissociative identity disorder, and concluded that “in terms of key symptoms of the disorder, people taught to simulate DID are largely indistinguishable from people actually diagnosed with DID” (2014).

On the other hand, DID is not the only psychological disorder for which prevalence rates have increased over time. For example, rates of obsessive–

EXPLAINING DISSOCIATIVE IDENTITY DISORDER

According to one explanation, dissociative identity disorder represents an extreme form of dissociative coping (Moskowitz & others, 2009). A very high percentage of patients with DID report having suffered extreme physical or sexual abuse in childhood—

Over time, alternate personalities are created to deal with the memories and emotions associated with intolerably painful experiences. Feelings of anger, rage, fear, and guilt that are too powerful for the child to consciously integrate can be dissociated into these alternate personalities. In effect, dissociation becomes a pathological defense mechanism that the person uses to cope with overwhelming experiences.

Although widely accepted among therapists who work with patients with DID, the dissociative coping theory is difficult to test empirically. One problem is that memories of childhood are notoriously unreliable. Since DID is usually diagnosed in adulthood, it is very difficult, and often impossible, to determine whether the reports of childhood abuse are real or imaginary.

Another problem with the “traumatic memory” explanation of dissociative identity disorder is that just the opposite effect occurs to most trauma victims—

Test your understanding of Personality and Dissociative Disorders with  .

.