Psychoanalytic Therapy

KEY THEME

Psychoanalysis is a form of therapy developed by Sigmund Freud and is based on his theory of personality.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the key assumptions and techniques of psychoanalytic therapy?

How do short-

term dynamic therapies differ from psychoanalysis, and what is interpersonal therapy?

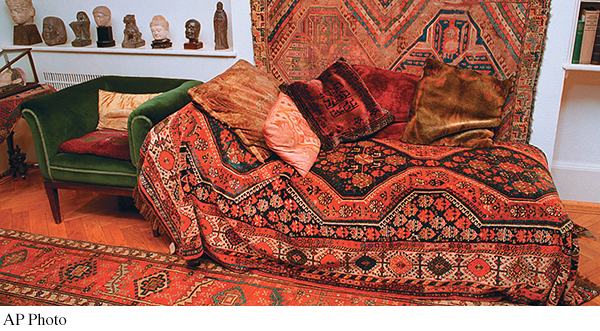

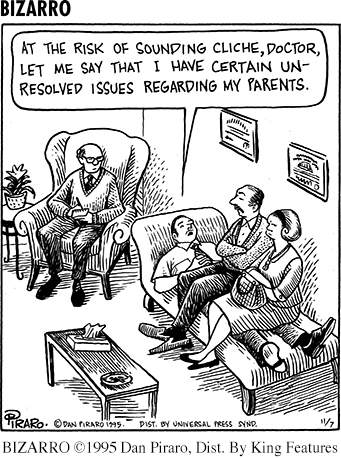

When cartoonists portray a psychotherapy session, they often draw a person lying on a couch and talking while a bearded gentleman sits behind the patient, passively listening. This stereotype reflects some of the key ingredients of traditional psychoanalysis, a form of psychotherapy originally developed by Sigmund Freud in the early 1900s. Although psychoanalysis was developed a century ago, its assumptions and techniques continue to influence many psychotherapies today (Borden, 2009; Lerner, 2008; Luborsky & Barrett, 2006).

Sigmund Freud and Psychoanalysis

The resistance accompanies the treatment step by step. Every single association, every act of the person under treatment must reckon with the resistance and represents a compromise between the forces that are striving towards recovery and opposing ones.

—Sigmund Freud (1912)

As a therapy, traditional psychoanalysis is closely interwoven with Freud’s theory of personality. As you may recall from Chapter 10 on personality, Freud stressed that early childhood experiences provided the foundation for later personality development. When early experiences result in unresolved conflicts and frustrated urges, these emotionally charged memories are repressed, or pushed out of conscious awareness. Although unconscious, these repressed conflicts continue to influence a person’s thoughts and behavior, including the dynamics of his relationships with others.

Psychoanalysis is designed to help unearth unconscious conflicts so that the patient attains insight into the real source of her problems. Through the intense relationship that develops between the psychoanalyst and the patient, long-

Freud developed several techniques to coax long-

Blocks in free association, such as a sudden silence or an abrupt change of topic, were thought to be signs of resistance. Resistance is the patient’s conscious or unconscious attempts to block the process of revealing repressed memories and conflicts (Luborsky & Barrett, 2006). Resistance is a sign that the patient is uncomfortably close to uncovering psychologically threatening material.

Dream interpretation is another important psychoanalytic technique. Because psychological defenses are reduced during sleep, Freud (1911) believed that unconscious conflicts and repressed impulses were expressed symbolically in dream images. For example, Freud (1900) suggested that a lion in a woman’s dream referred to her father who had a “beard which encircled his face like a Mane.” Often, the dream images were used to trigger free associations that might shed light on the dream’s symbolic meaning.

More directly, the psychoanalyst sometimes makes carefully timed interpretations, explanations of the unconscious meaning of the patient’s behavior, thoughts, feelings, or dreams. The timing of such interpretations is important. If an interpretation is offered before the patient is psychologically ready to confront an issue, he may reject the interpretation or respond defensively, increasing resistance (Prochaska & Norcross, 2014).

One of the most important processes that occurs in the relationship between the patient and the psychoanalyst is called transference. Transference occurs when the patient unconsciously responds to the therapist as though the therapist were a significant person in the patient’s life, often a parent. The psychoanalyst encourages transference by purposely remaining as neutral as possible. In other words, the psychoanalyst does not reveal personal feelings, take sides, make judgments, or actively advise the patient. This therapeutic neutrality is designed to produce “optimal frustration” so that the patient transfers and projects unresolved conflicts onto the psychoanalyst (Magnavita, 2008). These conflicts are then relived and played out in the context of the relationship between the psychoanalyst and the patient.

All of these psychoanalytic techniques are designed to help the patient see how past conflicts influence her current behavior and relationships, including her relationship with the psychoanalyst. Once these kinds of insights are achieved, the psychoanalyst helps the patient work through and resolve long-

The intensive relationship between the patient and the psychoanalyst takes time to develop. The traditional psychoanalyst sees the patient three times a week or more, often for years (Schwartz, 2003; Zusman & others, 2007). Freud’s patients were on the couch six days a week (Liff, 1992). Obviously, traditional psychoanalysis is a slow, expensive process that few people can afford. For those who have the time and the money, traditional psychoanalysis is still available.

Short-Term Dynamic Therapies

Most people entering psychotherapy today are not seeking the kind of major personality overhaul that traditional psychoanalysis is designed to produce. Instead, people come to therapy expecting help with specific problems. People also expect therapy to provide beneficial changes in a matter of weeks or months, not years.

Many different forms of short-

As in traditional psychoanalysis, the therapist uses interpretations to help the patient recognize hidden feelings and transferences that may be occurring in important relationships in her life (Kush, 2009)

One particularly influential short-

Interpersonal therapy may be brief or long-

IPT is used to treat eating disorders and substance use disorders as well as major depressive disorder. It is also effective in helping people deal with interpersonal problems, such as marital conflict, parenting issues, and conflicts at work (Bleiberg & Markowitz, 2008). In one innovative application, IPT was successfully used to treat symptoms of major depressive disorder in villagers in Uganda, demonstrating its effectiveness in a non-

Even though traditional, lengthy psychoanalysis is uncommon today, Freud’s basic assumptions and techniques continue to be influential. Contemporary research has challenged many of Freud’s original ideas. However, modern researchers continue to study the specific factors that seem to influence the effectiveness of basic Freudian techniques, such as dream analysis, interpretation, transference, and the role of insight in reducing psychological symptoms (Glucksman & Kramer, 2004; Luborsky & Barrett, 2006).