Biomedical Therapies

KEY THEME

The biomedical therapies are medical treatments for the symptoms of psychological disorders and include medication and electroconvulsive therapy.

KEY QUESTIONS

What medications are used to treat the symptoms of schizophrenia, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder, and how do they achieve their effects?

What is electroconvulsive therapy, and what are its advantages and disadvantages?

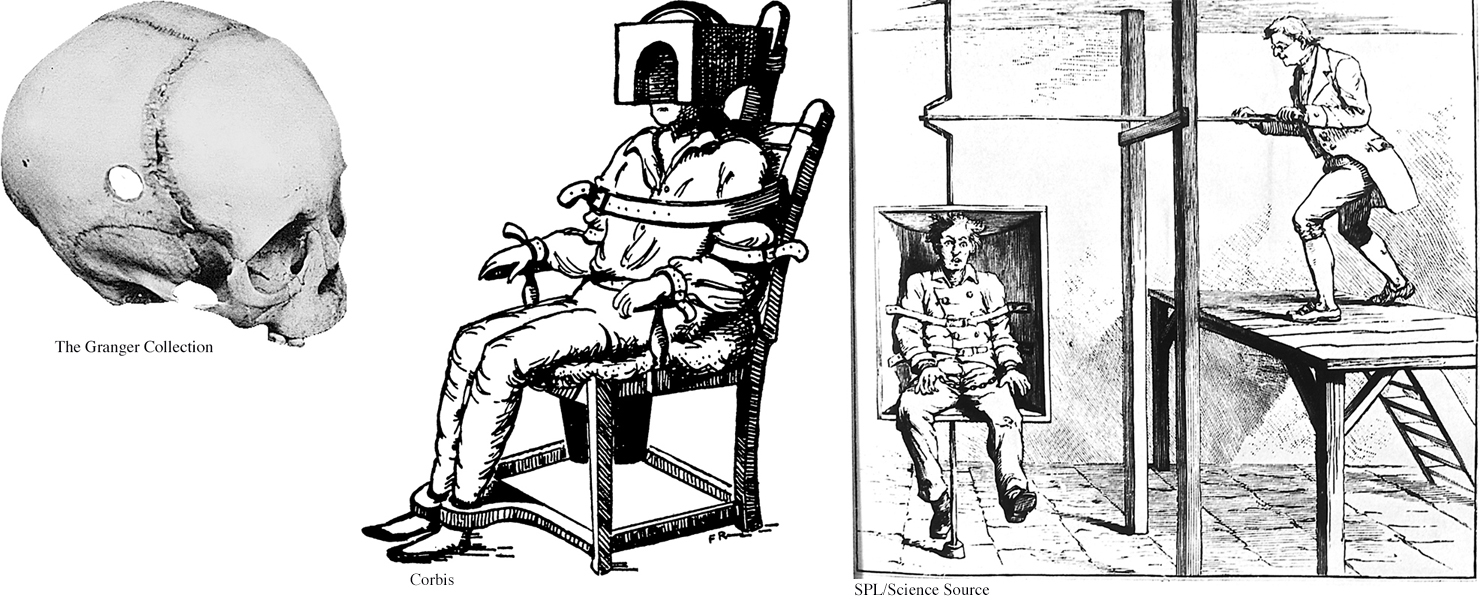

Medical treatments for psychological disorders actually predate modern psychotherapy by hundreds of years. In past centuries, patients were whirled, soothed, drenched, restrained, and isolated—

For the most part, it was not until the twentieth century that effective biomedical therapies were developed to treat the symptoms of mental disorders. Today, the most common biomedical therapy is the use of psychotropic medications—prescription drugs that alter mental functions and alleviate psychological symptoms. You can see how medications affect neurotransmitter functioning in the synapses between neurons in Figure 2.7 on page 52. Although often used alone, psychotropic medications are increasingly combined with psychotherapy (Kaut & Dickinson, 2007; Sudak, 2011).

Antipsychotic Medications

For more than 2,000 years, traditional practitioners of medicine in India used an herb derived from the snakeroot plant to diminish the psychotic symptoms commonly associated with schizophrenia: hallucinations, delusions, and disordered thought processes (Bhatara & others, 1997). The same plant was used in traditional Japanese medicine to treat anxiety and restlessness (Jilek, 1993). In the 1930s, Indian physicians discovered that the herb was also helpful in the treatment of high blood pressure. They developed a synthetic version of the herb’s active ingredient, called reserpine.

615

Reserpine first came to the attention of American researchers as a potential treatment for high blood pres sure. But it wasn’t until the early 1950s that American researchers became aware of research in India demonstrating the effectiveness of reser-

It was also during the 1950s that French scientists began investigating the psychoactive properties of another drug, called chlorpromazine. Like reserpine, chlorpromazine diminished the psychotic symptoms commonly seen in schizophrenia. Hence, reserpine and chlorpromazine were dubbed antipsychotic medications. Because chlorpromazine had fewer side effects than reserpine, it nudged out reserpine as the preferred medication for treating schizophrenia-

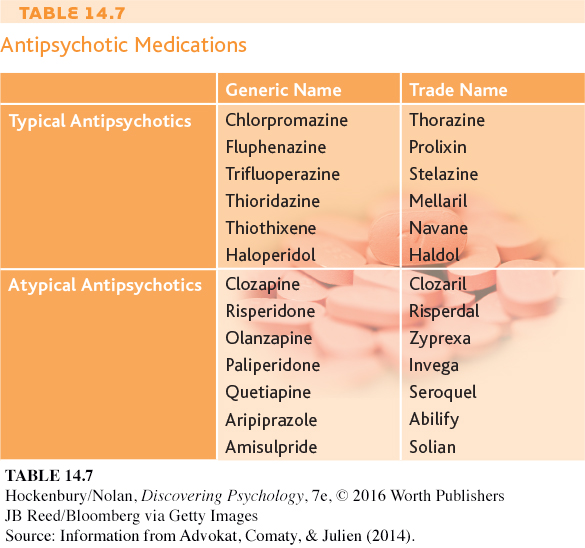

How do these drugs diminish psychotic symptoms? Reserpine and chlorpromazine act differently on the brain, but both drugs reduce levels of the neurotransmitter called dopamine. Since the development of these early drugs, more than 30 other antipsychotic medications have been developed (see Table 14.7). These antipsychotic medications also act on dopamine receptors in the brain (Abi-

The first antipsychotics effectively reduced the positive symptoms of schizophrenia—

616

DRAWBACKS OF ANTIPSYCHOTIC MEDICATIONS

Even though the early antipsychotic drugs allowed thousands of patients to be discharged from hospitals, these drugs had a number of drawbacks. First, they didn’t actually cure schizophrenia. Psychotic symptoms often returned if a person stopped taking the medication.

Second, the early antipsychotic medications were not very effective in eliminating the negative symptoms of schizophrenia—

Third, the antipsychotics often produced unwanted side effects, such as dry mouth, weight gain, constipation, sleepiness, and poor concentration (Stahl, 2009).

Fourth, the fact that the early antipsychotics globally altered brain levels of dopamine turned out to be a double-

Even more disturbing, the long-

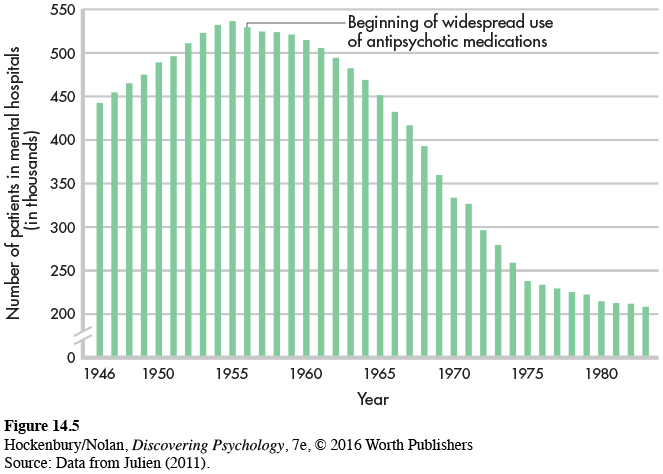

Closely tied to the various side effects of the first antipsychotic drugs is a fifth problem: the “revolving door” pattern of hospitalization, discharge, and rehospitalization. Schizophrenic patients, once stabilized by antipsychotic medication, were released from hospitals into the community. But because of either the medication’s unpleasant side effects or inadequate medical follow-

617

THE ATYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS

Beginning around 1990, a second generation of antipsychotic drugs began to be introduced. Called atypical antipsychotic medications, these drugs affect brain levels of dopamine and serotonin. The first atypical antipsychotics were clozapine and risperidone. More recent atypical antipsychotics include olanzapine, sertindole, and quetiapine.

The atypical antipsychotics have several advantages over the older antipsychotic drugs (Advokat, Comaty, & Julien, 2014). First, the new drugs are less likely to cause movement-

The atypical antipsychotic medications also appear to lessen the incidence of the “revolving door” pattern of hospitalization and rehospitalization. As compared to discharged patients taking the older antipsychotic medications, patients taking risperidone or olanzapine are much less likely to relapse and return to the hospital (Bhanji & others, 2004).

The atypical antipsychotic medications sparked considerable hope for better therapeutic effects, fewer adverse reactions, and greater patient compliance. Although they were less likely to cause movement-

Antianxiety Medications

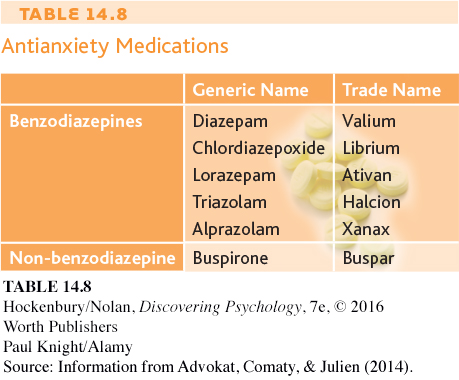

Anxiety that is intense and persistent can be disabling, interfering with a person’s ability to eat, sleep, and function. Antianxiety medications are prescribed to help people deal with the problems and symptoms associated with pathological anxiety (see Table 14.8).

The best-

618

Taken for a week or two, and in therapeutic doses, the benzodiazepines can effectively reduce anxiety levels. However, the benzodiazepines have several potentially dangerous side effects. First, they can reduce coordination, alertness, and reaction time. Second, their effects can be intensified when they are combined with alcohol and many other drugs, including over-

Third, the benzodiazepines can be physically addictive if taken in large quantities or over a long period of time. If physical dependence occurs, the person must withdraw from the drug gradually, as abrupt withdrawal can produce life-

An antianxiety drug with the trade name Buspar has fewer side effects. Buspar is not a benzodiazepine, and it does not affect the neurotransmitter GABA. In fact, exactly how Buspar works is unclear, but it is believed to affect brain dopamine and serotonin levels (Davidson & others, 2009). Regardless, Buspar relieves anxiety while allowing the individual to maintain normal alertness. It does not cause the drowsiness, sedation, and cognitive impairment that are associated with the benzodiazepines. And Buspar seems to have a very low risk of dependency and physical addiction.

However, Buspar has one major drawback: It must be taken for two to three weeks before anxiety is reduced. While this decreases Buspar’s potential for abuse, it also decreases its effectiveness for treating acute anxiety.

Another new medication that has been explored as a treatment for anxiety disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder is MDMA, short for methylenedioxy-

Lithium

In Chapter 13, on psychological disorders, we described bipolar disorder, previously known as manic depression. The medication most commonly used to treat bipolar disorder is lithium, a naturally occurring substance. Lithium counteracts manic symptoms, and to a lesser degree depressive symptoms, in bipolar patients (Nivoli & others, 2010; Nivoli & others, 2012). Its effectiveness in treating bipolar disorder has been well established since the 1960s (Preston & others, 2008).

As a treatment for bipolar disorder, lithium can prevent acute manic episodes over the course of a week or two. Once an acute manic episode is under control, the long-

Like all other medications, lithium has potential side effects. If the lithium level is too low, manic symptoms persist. If it is too high, lithium poisoning may occur, with symptoms such as vomiting, muscle weakness, and reduced muscle coordination. Consequently, the patient’s lithium blood level must be carefully monitored.

How lithium works was once a complete mystery. Lithium’s action was especially puzzling because it prevented mood disturbances at the manic end of the emotional spectrum and to some degree at the depressive end as well. It turns out that lithium affects levels of an excitatory neurotransmitter called glutamate, which is found in many areas of the brain. Apparently, lithium stabilizes the availability of glutamate within a narrow, normal range, preventing both abnormal highs and abnormal lows (Keck & McElroy, 2009; Malhi & others, 2013).

619

Bipolar disorder can also be treated with an anticonvulsant medicine called Depakote. Originally used to prevent epileptic seizures, Depakote seems to be especially helpful in treating those who rapidly cycle through bouts of bipolar disorder several times a year. It’s also useful for treating bipolar patients who do not respond to lithium (Davis & others, 2005).

Antidepressant Medications

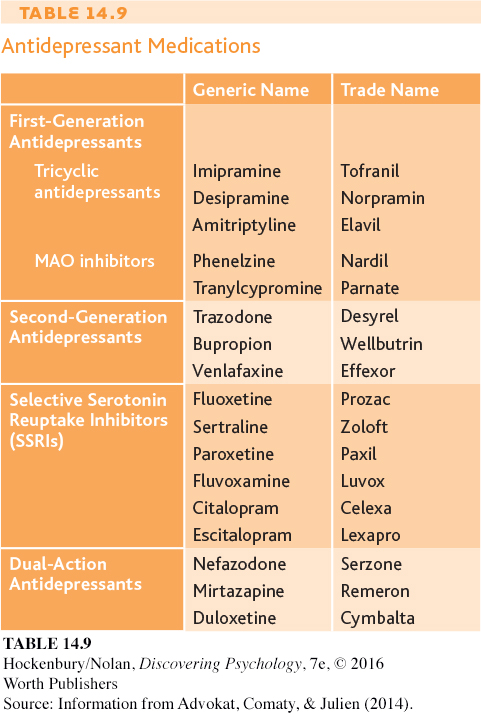

The antidepressant medications counteract the classic symptoms of major depressive disorder—

Tricyclics and MAO inhibitors can be effective in reducing depressive symptoms, but they can also produce numerous side effects (Holsboer, 2009). Tricyclics can cause weight gain, dizziness, dry mouth and eyes, and sedation. And, because tricyclics affect the cardiovascular system, an overdose can be fatal. As for the MAO inhibitors, they can interact with a chemical found in many foods, including cheese, smoked meats, and red wine. Eating or drinking these while taking an MAO inhibitor can result in dangerously high blood pressure, leading to stroke or even death.

The search for antidepressants with fewer side effects led to the development of the second generation of antidepressants. Second-

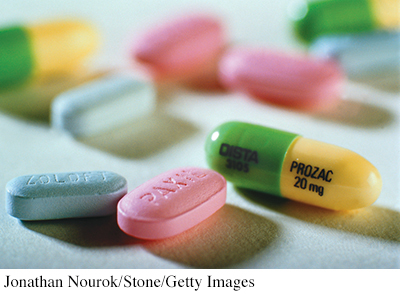

In 1987, the picture changed dramatically with the introduction of a third group of antidepressants, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, abbreviated SSRIs. Rather than acting on multiple neurotransmitter pathways, the SSRIs primarily affect the availability of a single neurotransmitter—

620

Prozac was specifically designed to alleviate depressive symptoms with fewer side effects than earlier antidepressants. It achieved that goal with considerable success. Although no more effective than tricyclics or MAO inhibitors, Prozac and the other SSRI antidepressants tend to produce fewer, and milder, side effects. But no medication is risk-

Partly because of its relatively mild side-

Since the original SSRIs were released, several new antidepressants have been developed, including Serzone and Remeron. These antidepressants, called dual-

One promising new treatment is an experimental drug called ketamine (Larkin & Beautrais, 2011). As discussed in Chapter 4, ketamine is used in high doses as an anesthetic, and called Special K when sold as a street drug. In one study, 71% of severely depressed patients who received intravenous ketamine saw a decrease in depressive symptoms within just one day, as compared with 0% of those taking placebo (Zarate & others, 2006). There were some serious side effects from ketamine, such as hallucinations, but none that lasted more than two hours.

Despite its impressive effectiveness, ketamine is likely to be used only in emergency situations, in large part because its effects tend to last no more than a week. However, ketamine’s fast response time means that seriously depressed people who visit the ER might be able to forgo inpatient treatment. During the time it takes for ketamine to wear off, more traditional antidepressants and psychotherapy might have time to start working. There also is evidence that the use of ketamine reduces suicide rates (DiazGranados & others, 2010).

Think Like a SCIENTIST

How would a “party drug” end up being prescribed for depression? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Ketamine.

Antidepressants are often used in the treatment of disorders other than depression, sometimes in combination with other drugs. For example, the SSRIs are commonly prescribed to treat anxiety disorders, obsessive–

With so many antidepressants available today, which should be prescribed? Many factors, including previous attempts with antidepressants, possible interactions with other medications, and personal tolerance of side effects, can influence this decision. Currently, medications are typically prescribed on a “trial-

Many researchers believe that genetic differences may explain why people respond so differently to antidepressants and other psychotropic medications (Crisafulli & others, 2011). The new field of pharmacogenetics is the study of how genes influence an individual’s response to drugs (Nurnberger, 2009). As this field advances, it may help overcome the trial-

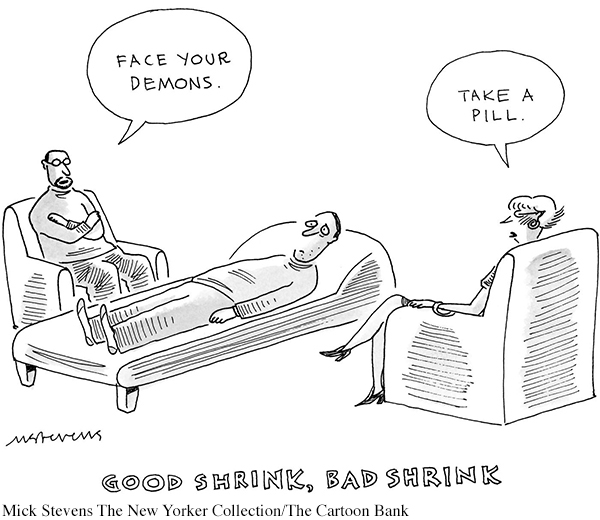

How do antidepressants and psychotherapy compare in their effectiveness? Several large-

621

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

Psychotherapy and the Brain

As we discussed in Chapter 13, major depressive disorder is characterized by a variety of physical symptoms and includes changes in brain activity (Abler & others, 2007; Kempton & others, 2011). Antidepressants are assumed to work by changing brain chemistry and activity. Does psychotherapy have the same effect?

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that, for some disorders, psychotherapy and medications lead to similar changes in brain activity?

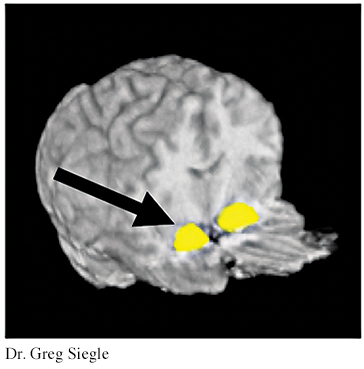

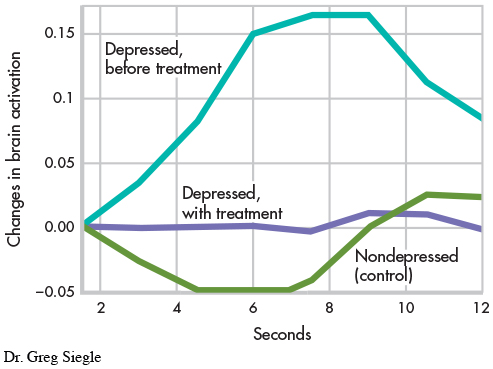

To address this question, fMRI scans were done on 27 people with major depressive disorder and compared to a matched group of 25 normal control subjects who were not depressed (Siegle & others, 2007). Compared with the nondepressed adults, the depressed individuals showed altered brain activity following an emotional task and a cognitive task. These tasks were chosen because major depressive disorder tends to affect both people’s emotional responses and their thought processes.

For the emotional task, both groups were asked to briefly view negative emotional words that they perceived to be relevant for them personally. The depressed people showed increased activity in the amygdala. The control group, made up of people who were not depressed, did not exhibit activity in the amygdala following this task. In addition, after completing a cognitive task in which they were asked to mentally sort a short list of numbers, depressed people showed less activity in the prefrontal cortex than did those in the control group.

A sample of nine of the depressed people in this study then completed 14 weeks of cognitive therapy (DeRubeis & others, 2008). After treatment, the brain activity of the people treated for depression resembled that of the control group. The posttreatment brain scan shown here displays the activity in the amygdala in response to viewing the negative emotional word “ugly” for people in the control group or for people treated for depression. The graph highlights the differences among these two groups and a third group, people who have not yet been treated for depression. People who do not suffer from depression are indicated in green; people with depression who have been treated with cognitive therapy are indicated in purple; and people with depression who have not been treated are indicated in turquoise. There is increased brain activation only among the third group, the depressed people before treatment.

Interestingly, the changes in brain activation that result from psychotherapy are similar to changes that result from medications. For example, in a study of people with major depressive disorder, PET scans revealed that patients who took the antidepressant Paxil and patients who completed interpersonal therapy (discussed earlier in this chapter) showed a trend toward more normalized brain functioning (Brody & others, 2001). Activity declined significantly in brain regions that had shown abnormally high activity before treatment began. Similar results were found in a study comparing a different antidepressant, Effexor, and a different type of psychotherapy, cognitive-

As these findings emphasize, psychotherapy—

622

CRITICAL THINKING

Do Antidepressants Work Better Than Placebos?

Are antidepressants just fancy placebos? Consider this statement by psychologist Irving Kirsch on a 2012 episode of the TV news show 60 Minutes: “The difference between the effect of the placebo and the effect of an antidepressant is minimal for most people.” Interviewer Lesley Stahl was astounded: “So, you’re saying if they took a sugar pill, they’d have the same effect?”

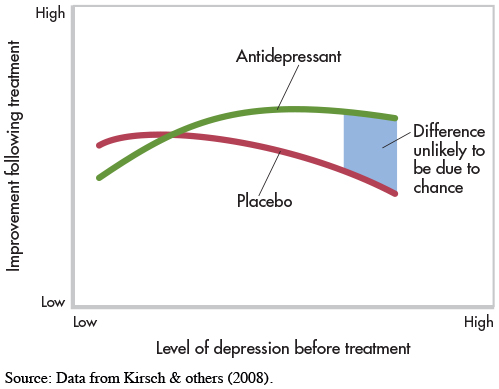

Kirsch’s surprising statement is based on meta-

Kirsch and his colleagues found that most patients improved with either antidepressants or placebos (see graph below). Antidepressants were found to work better than placebos for some patients—

The placebo effect, as discussed in Chapter 1 on page 29 and Chapter 12 on page 512, has been well documented and is not limited to psychological disorders. Placebos have been demonstrated to lead to improvements in a range of health problems, including the management of pain and the treatment of symptoms related to the gastrointestinal, endocrine, cardiovascular, respiratory, and immune systems (Price & others, 2008). For example, in one study, patients with Parkinson’s disease experienced improved movement after taking a placebo. In another study, people who simply held a bottle of ibuprofen reported lower levels of pain than people who did not hold the bottle (Price & others, 2008; Rutchick & Slepian, 2013).

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that antidepressants are a much more effective treatment than placebos for the vast majority of cases of depression?

You may now be thinking that the placebo effect means that any improvements are just imaginary. But as described in Chapter 12 on page 512, brain imaging shows that placebos lead to real biological changes (Meissner & others, 2011). In response to a placebo, patients with Parkinson’s disease experience increased dopamine activation, pain patients saw less neural activity in the parts of the brain associated with pain, and depressed patients experienced metabolic increases in the same parts of the brain that respond to antidepressants (Price & others, 2008). Interestingly, another study found that the effect of a placebo on Parkinson’s symptoms was stronger when patients thought the placebo was expensive than when they thought it was cheap (Espay & others, 2015). Either way, improvements tend to come without the side effects and potentially high costs of “real” medication.

Kirsch argues that we should question whether it’s worth the risk of giving a “real” drug when a placebo is just as effective for some people. But this may be a hard sell to physicians and patients who believe that antidepressants are the most effective treatment for depression. Other researchers view the pharmaceutical industry, which has immense resources, as contributing to exaggerated reports of the effects of medications (Cuijpers & others, 2010). Pharmaceutical companies have billions of dollars at stake in convincing physicians and patients that their medications are effective, and they spend more than $25 billion each year just in the United States marketing their drugs (Kornfield & others, 2013).

While acknowledging concerns about the influence of the pharmaceutical industry, other researchers have found that anti-

As more is known about the effects of placebos, there is more discussion about how to harness their power. Researchers suggest that clinicians should receive training on ethical ways to openly and successfully prescribe placebos by educating patients about their effectiveness (Brody & Miller, 2011). In the past, clinicians believed that successful treatment with placebos required that the patients believe the placebo was real, but recent research questions this premise. One study on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) observed improvement in patients even after they were told they were receiving “placebo pills made of an inert substance, like sugar pills, that have been shown in clinical studies to produce significant improvement in IBS symptoms through mind–

Research on the placebo effect continues to accumulate. However, despite Kirsch’s argument, it’s important to remember that many people have been and continue to be helped by antidepressant medication. Other treatment options, such as psychotherapy, may be unavailable. So, if antidepressants are helping you, you should continue to take them as directed by your physician. It can be dangerous to stop taking antidepressant medications without guidance from a physician.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

Why do you think studies that found differences are more likely to be published than studies that found no differences?

What is the ethical problem with giving a patient a placebo and saying it is an antidepressant?

Why might simply giving a patient a placebo openly not work without additional education?

Electroconvulsive Therapy

As we have just seen, millions of prescriptions are written for antidepressant medications in the United States every year. In contrast, a much smaller number of patients receive electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT, as a medical treatment for severe cases of major depressive disorder. Also known as electroshock therapy or shock therapy, electroconvulsive therapy involves using a brief burst of electric current to induce a seizure in the brain, much like an epileptic seizure. Although ECT is most commonly used to treat major depressive disorder, it is occasionally used to treat mania, schizophrenia, and other severe mental disorders (Nahas & Anderson, 2011).

ECT is a relatively simple and quick medical procedure, usually performed in a hospital. The patient lies on a table. Electrodes are placed on one or both of the patient’s temples, and the patient is given a short-

623

While the patient is unconscious, a split-

MYTH SCIENCE

Is it true that electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), once called “shock therapy,” causes permanent brain damage and memory loss?

In the short term, ECT is a very effective treatment for severe cases of major depressive disorder: About 80 percent of patients improve (Rasmussen, 2009). ECT also relieves the symptoms of depression very quickly, typically within days. Author Donald Antrim once described his experience with ECT as “the color came back on” (Sullivan, 2014). And as the symptoms of depression decrease, ECT patients’ quality of life tends to increase to a level similar to that in people without depression (McCall & others, 2013). Because of its rapid therapeutic effects, ECT can be a lifesaving procedure for extremely suicidal or severely depressed patients (Nahas & Anderson, 2011). Such patients may not survive for the several weeks it takes for antidepressant drugs to alleviate symptoms. Antrim, for example, credits ECT with saving his life (Sullivan, 2014).

624

Typically, ECT is used only after other forms of treatment, including both psychotherapy and medication, have failed to help the patient, especially when depressive symptoms are severe. For some people, such as elderly individuals, ECT may be less dangerous than antidepressant drugs. In general, the complication rate from ECT is very low.

Nevertheless, inducing a brain seizure is not a matter to be taken lightly. ECT has potential dangers. Serious cognitive impairments can occur, such as extensive amnesia and disturbances in language and verbal abilities. However, fears that ECT might produce brain damage have not been confirmed by research (Eschweiler & others, 2007; McDonald & others, 2009).

Perhaps ECT’s biggest drawback is that its antidepressive effects can be short-

At this point, you may be wondering why ECT is not in wider use. The reason is that ECT is considered controversial (Dukart & others, 2014; Shorter, 2009). Not everyone agrees that ECT is either safe or effective.

Some have been quite outspoken against it, arguing that its safety and effectiveness are not as great as its supporters have claimed (Andre, 2009). The controversy over ECT is tied to its portrayal in popular media over time. The use of ECT declined drastically in the 1960s and 1970s when it was depicted in many popular books and movies, including One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, as a brutal treatment with debilitating side effects (Swartz, 2009). Its use has increased greatly since that time, especially in the past decade or two, with ECT now available in most major metropolitan areas in the United States (Shorter, 2009).

How does ECT work? Despite many decades of research, it’s still not known exactly why electrically inducing a convulsion relieves the symptoms of major depressive disorder (Michael, 2009). One theory is that ECT seizures may somehow “reboot” the brain by depleting and then replacing important neurotransmitters (Swartz, 2009).

Some new, experimental treatments suggest that those seizures may not actually be necessary. That is, it may be possible to provide lower levels of electrical current to the brain than traditional ECT delivers and still reduce severe symptoms of depression and other mental illnesses. For example, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is similar to ECT, but uses a small fraction of the electricity (Brunoni & others, 2012; Shiozawa & others, 2014). Another, related treatment is transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which involves stimulation of certain regions of the brain with magnetic pulses of various frequencies. Unlike ECT, both tDCS and TMS require no anesthetic, induce no seizures, and can be conducted in a private doctor’s office rather than a hospital (Dell’Osso & Altamura, 2014; Janicak & others, 2010; Rosenberg & Dannon, 2009).

Yet another experimental treatment, vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), involves the surgical implantation of a device about the size of a pacemaker into the left chest wall. The device provides brief, intermittent electrical stimulation to the left vagus nerve, which runs through the neck and connects to the brain stem (McClintock & others, 2009). Finally, deep brain stimulation (DBS) utilizes electrodes surgically implanted in the brain and a battery-

Keep in mind that tDCS, TMS, VNS, and DBS are still experimental, and some of the research findings are mixed (Dougherty & others, in press). And like ECT, the specific mechanism by which they may work is not entirely clear. Still, researchers are hopeful that these techniques will provide additional viable treatment options for people suffering from severe psychological symptoms (McDonald & others, 2009).

625

Test your understanding of Biomedical Therapies with  .

.