REGION

11.1

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Describe the possible futures of place and region, and explain their driving forces.

Is it possible to use maps to detect future trends related to culture regions? Some geographers look at maps and do indeed see regional homogenization. David Nemeth, for example, expresses the view that regions are “being crushed and recycled into a bland, ambiguous amalgam,” producing “something akin to a vast parking lot of global scale.” Without question, people in all parts of the world must confront the choice between their traditional attachment to place and local culture on the one hand and the attractions of globalization-driven cosmopolitanism on the other. Indeed, the fear of losing the distinctiveness of place—and with it, the associated cultural diversity— seems to be a recurring and longstanding theme in modern life. Geographer Wilbur Zelinsky observed that the lament over placelessness and vanishing diversity can be traced back in time for decades if not centuries.

459

Zelinsky argued that although there has been a long-expressed fear of homogenization, it is difficult to find the empirical evidence to demonstrate that it has yet come to pass. He sought to answer the question “Over the past few centuries what effects has the enormous process of modernization—and globalization in particular—had on the character, life, and durability of all places and regions?” Focusing on the United States, he first undermines the assumption that the country was historically a disparate collection of diverse regional cultures. In fact, standardizing and homogenizing practices have been widespread since the eighteenth century, addressing language, communications, transportation, and land registry to name just a few. During the same historical period, however, one can also find identifiable culture areas, such as New England and Dutch-Flemish New York.

Building on this historical insight, Zelinsky assesses the contemporary status of a variety of cultural-geographic phenomena, from architectural forms to food preferences. His findings show that the present parallels the past; while homogenizing forces have grown stronger and more pervasive, differentiation is evident everywhere. He concludes that place-making and regionalization in the United States are increasing and “promises to do so indefinitely” into the future. In other words, he found, paradoxically, that convergence and divergence are both occurring. If we extend Zelinsky’s U.S. study to other parts of the world, it appears that the future homogenization of regional and cultural difference is far from predetermined, because the forces of globalization operate to simultaneously standardize and diversify cultural practices and meanings.

THE UNEVEN GEOGRAPHY OF DEVELOPMENT

Most cultural geographers expect that regional diversity will persist. In particular, the familiar core-periphery concept is just as relevant as ever, especially where development is concerned. Some regions—forming the core—are moving ahead and prospering, while many others—the periphery—fall further and further behind. Global interdependence has not evened out the differences between the haves and have-nots; in many ways, it increases them. What do we mean by falling behind or moving ahead? One clear measure is global wealth distribution. There is now a transnational class of the super-rich, the 0.25 percent of the world’s population that owns as much wealth as the other 99.75 percent. Most of them live in a First World core consisting of Anglo America, the European Union (EU), the coastal zone of East Asia, and Australia-New Zealand. As the greatest beneficiaries of globalizing processes, these regions are moving ahead of the remaining Third World peripheral lands.

Not all observers, however, agree that the global income gap is widening. In The New Geography of Global Inequality, Glenn Firebaugh argues that world core-periphery differences are not actually increasing. He points out that if one takes into account only the fact that the incomes of the richest nations are increasing at a greater rate than those of the poorest, it does look as if the rich are becoming richer faster, while the poor remain poor. Yet, this overlooks another fact: the many poorer countries contain only 10 percent of the world’s population, while those that are developing very rapidly (mostly Asian countries) contain more than 40 percent. Taking national population numbers into account, we see that global income gaps are, in fact, decreasing.

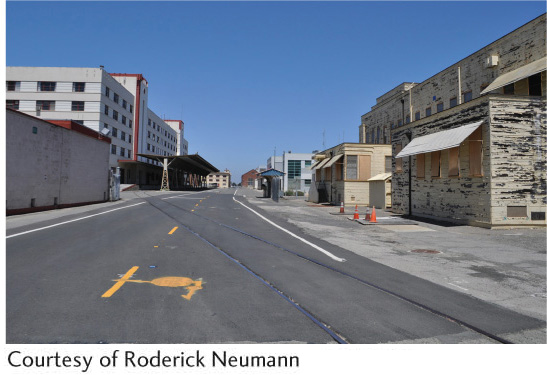

In the meantime, income gaps within nation-state boundaries are growing rapidly. Instead of core-periphery, another way to think about the unevenness of development is in terms of “fast” and “slow” worlds. In many ways, economic development speeds up daily life. The fast world is at the forefront of instantaneous global communication, where one can download the latest music and films from around the world or play the Tokyo stock market from one’s home computer in Seattle. The fast world is connected to high-speed broadband Internet; based in the world’s megacities; adaptable to rapid shifts in global trends of investment, trade, production, and consumption; and home to the transnational super-rich. The slow world consists of the hollowed-out rural landscapes, declining or abandoned manufacturing zones, and slums and shantytowns (Figure 11.2). Computers and Internet broadband service, even if available, are priced out of reach of most of the inhabitants of the slow world. Pieces of the periphery that lie adjacent to the core, such as Mexico’s northern border, scramble to join the privileged part of the world, to be fast rather than slow. As Mexican border cities’ recent experience with job loss to China demonstrates, for such regions, membership in the fast world can be fleeting.

460

British geographer Rob Shields, in Places on the Margin, concentrates on an array of places and regions of varying size that have been “left behind in the modern race for progress.” He finds peripheries even within the core. Often these places and regions become sites of illicit or stigmatized activities, such as the international trades in sex and illegal drugs. Says Shields, such “margins become signifiers of everything centers deny or repress.”

Tragically, places on the margin have also become key sites in the international trafficking of slave labor. Slavery, it turns out, is not a shameful practice consigned to the distant past, but an increasingly common phenomenon under globalization. Some believe that as many as 27 million people live in slavery worldwide, on every continent in the world save Antarctica. Traffickers prey on the most desperate and powerless of society’s castoffs. In the United States, California, Texas, and Florida lead the way in the increase in slave labor cases. Some of Florida’s famous orange juice, for example, was recently found to be harvested by illegal Mexican immigrants held against their wills in remote rural camps (Figure 11.3). The insatiable international demand for Brazil’s timber and beef has been met through the labor of captive workers held deep in the Amazon. Labor recruiters in Brazilian cities lure jobless workers to cut remote forestlands through false promises of good wages and housing. Once there, workers’ wages are withheld and they are prevented from leaving. Some are forced to work for years clearing forests to make way for cattle ranching. According to one Brazilian labor official, “Slave labor in Brazil is directly linked to deforestation.” The example of slavery shows how illicit activities can thrive in peripheries, such as rural Florida and the Brazilian Amazon.

ONE EUROPE OR MANY?

Looking at just one region of the world, geographer Ray Hudson echoes our question: “One Europe or many?” Local identities are asserting themselves within states at the same time that supranationalism is touted as the path to “one Europe.” He opts decidedly for “many,” saying that one main role of the European Union should be to promote “complex geographies of identities.” Hudson also concludes that power and wealth will not be evenly distributed geographically in Europe, contributing to the maintenance of many cultural regions.

A similar outlook leads geographer Michael Keating to speak of a “new regionalism” in Europe, and David Hooson went so far as to suggest that globalization actually strengthens people’s bond between place and identity. This strengthening is suggested by the rise of ethnic separatism in countries as diverse as Spain, the United Kingdom, and Serbia and Montenegro. As people find that the forces of globalization are eroding cultural norms, customs, and practices, local political movements that seek to reinvigorate ethnic identities rooted in place may arise in reaction. Major political-geographic events such as the disintegration of the Soviet Union or the creation and expansion of the EU can have complex effects on cultural identities. The recent expansion of the EU is likely to bring a host of unintended and surprising outcomes for culture regions. In some newly independent former Soviet territories, such as Estonia, ethnic Russian immigrants have become a disadvantaged minority group. New post-Soviet states have used their membership in the EU to reassert national ethnic heritage and redefine themselves culturally as “Western.”

461

Moreover, globalization means that local economies are linked more tightly with the economic fortunes of distant countries. Global economic downturns can thus produce powerful centrifugal forces. This was brought home to EU citizens everywhere in the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2008-2009. A 2013 Pew Research poll of EU citizens found that the economic crisis has become a political crisis for the future of the EU. Public support for EU integration plummeted since its highs in the first decade of the twenty-first century (Figure 11.4). In addition, attitudes toward the EU project are diverging among member states, with Germans showing strong support and a French majority expressing dissatisfaction. Most worrisome for future EU unity are the results that show support for the EU dropping among 18- to 29-year-olds in all countries. While few observers expect the EU to split up, these results make clear that national cultural differences remain strong and that the transition to a single European identity remains somewhere in the distant future.

GLOCALIZATION

The theme of region, then, seems to suggest that a new human mosaic is forming in the age of globalization. Rapid change is pervasive, but its direction differs from one location to the next. The future will not be like the past, but it will also not be monochromatic.

462

The interaction between global and local prompted geographer Erik Swyngedouw to promote the term glocalization to describe the consequences. In brief, he argues that the outcome of this interaction involves change both in the regional way of life and in the globalizing force. For example, transnational corporations often have to adapt their product lines to local norms and preferences or adjust their production practices to local labor and environmental laws. Put differently, glocalization is a process that ensures the survival of culture regions and places in the future. These considerations, prompted by the culture region theme, lead us to conclude that a planetary culture is almost certainly illusory and that potent forces are at work to prevent homogenization.

glocalization

The process by which global forces of change interact with local cultures, altering both in the process.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE INTERNET

Has the Internet reduced the importance of geography or the viability of regions? Journalist Thomas Friedman makes exactly that claim in The World Is Flat, his international best-selling book on globalization’s effects. He singles out the Internet as a key technology that allows the global interconnectivity of individuals and institutions. Once place-bound human activities now occur on the Internet almost instantaneously on a global scale. The Internet can cross borders, both political and cultural; it breaks down barriers; it eliminates the effects of distance. According to Friedman, the Internet, among other globalizing phenomenon, is leveling the differences among nations and their citizens.

463

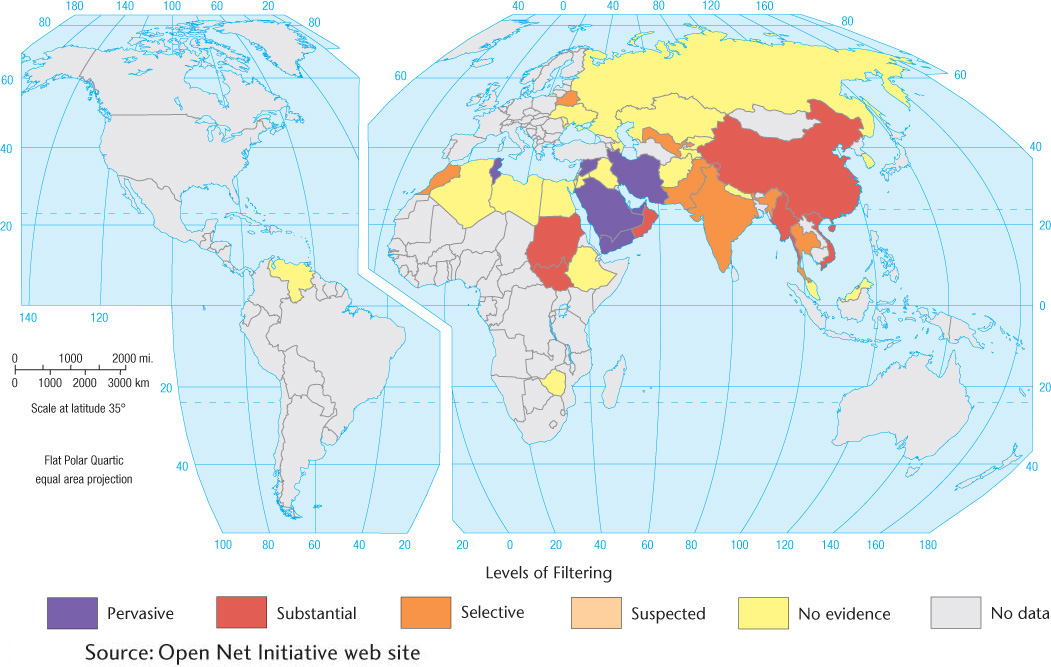

Many observers disagree with Friedman’s assessment. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz suggests that “in many ways the world is getting less flat” under globalization. The reality of the Internet’s influence is very complex and ultimately leaves culture regions intact. We must remember that—like many technological innovations—the Internet is a tool with many, often unanticipated, uses. From al-Qaeda to French ultra-nationalists to First Nations in Canada, the Internet is used as a tool to emphasize and defend geographies of cultural difference. Rather than making national borders irrelevant, the Internet can sometimes highlight differences between different countries. For example, governments can monitor, censor, regulate, and block access to the Internet (Figure 11.5; see Subject to Debate). Ironically, Friedman’s home paper, the New York Times, is periodically edited or blocked when it publishes articles unfavorable to Chinese government figures.

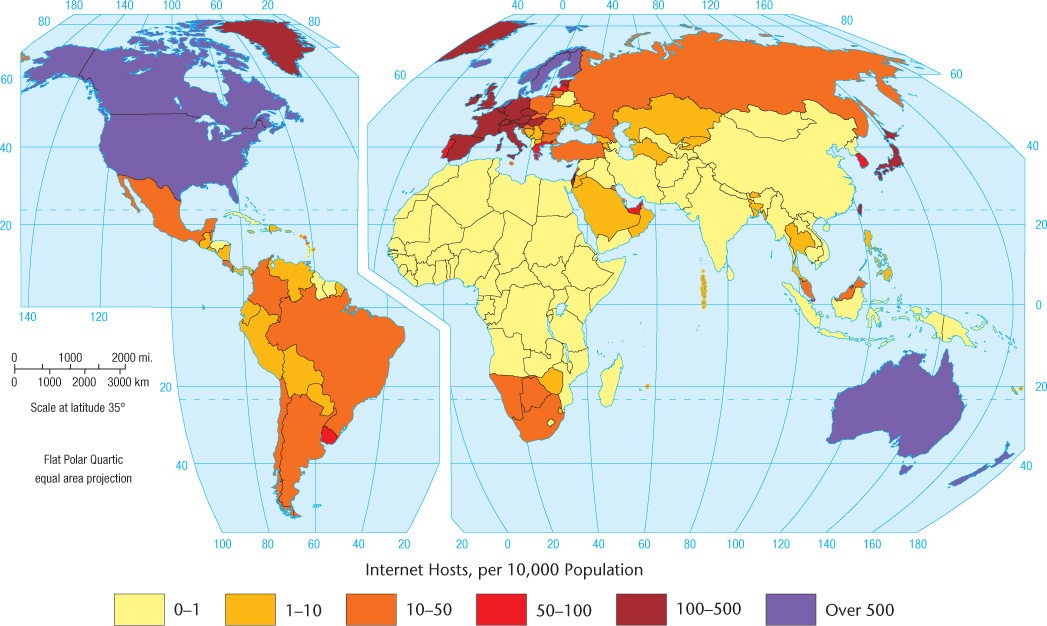

Although the constraints of geography are increasingly recognized, there is no question that the Internet has been very effective in creating new forms of social interaction, including the creation of virtual communities. We might ask, as John Barlow does, “Is there a there in cyberspace?” Does the Internet contain a geography at all? Certainly, places—at least as understood by cultural geographers—cannot be created on the Internet. For starters, these “virtual places” lack a cultural landscape and a cultural ecology. In the broader context, on a worldwide scale, human diversity is poorly portrayed in cyberspace. “Old people, poor people, the illiterate, and the continent of Africa” seem not to be “there,” as Barlow notes (Figure 11.6). Users usually end up “meeting” others much like themselves on the Internet. More important, the breath and spirit of place cannot exist in cyberspace. Barlow, resorting to a Hindu term, calls this missing essence prana. These are not real places, nor can they ever be.

464

Subject To Debate: THE INTERNET: Global Tool for Democracy or Repression

Subject To Debate

THE INTERNET: Global Tool for Democracy or Repression

In a few short years, the Internet has become the most important medium for the global exchange of information and ideas. Many argue that the expansion of this global network will spread democratic ideals of citizen participation in government, freedom of expression, and individual liberty. Others suggest that the Internet, like other technologies of mass communication, can be used for any number of political and cultural ends, including the repression of public dissent.

The case of China illustrates the debate over the global expansion of the Internet. China represents the largest and fastest-growing market for Western-based Internet companies, and industry giants such as Google and Yahoo! have established subsidiaries there. These and other Western companies stress the power of the Internet to promote freedom of thought, creativity, and social equity through the widespread dissemination of information. The companies argue that their very presence and the access they provide to more information for increasing numbers of Chinese citizens are in and of themselves politically and culturally liberating.

There are signs, however, that the Internet in China can also function as an effective government tool to suppress dissent. In 2004 Yahoo! provided personal information to the Chinese government about a journalist’s online pro-democracy writings. The government courts sentenced the journalist to 10 years in prison. Google was allowed to establish a subsidiary in China in 2006 only by complying with the government’s censorship policies. The company developed a Chinese version of its search engine that automatically blocks results from searches on terms such as Tibet or Tiananmen Square. Cisco Systems designed the software behind the “Great Firewall of China,” the feature of the Internet in China that filters all online information as it crosses the country’s borders. The Great Firewall can block access to web sites as well as individual pages from a site. Terms such as democracy and human rights tend to trigger the Firewall.

In 2008, the Chinese government used its control of the Internet to suppress information on its military crackdown on Tibetan protests and simultaneously foment nationalistic outrage among Han Chinese against the Tibetans. Then, in 2010, Google announced that it would no longer cooperate with China’s Internet censorship program. Google had discovered that a cyberattack on its computers originating from China was an attempt to access the accounts of Gmail users who were advocates of human rights in China. For the time being, the Chinese government has allowed Google to continue operating in China.

Continuing the Debate

What does the case of Google in China tell us about the power of the Internet? Consider these questions:

•Is China a unique case or just an extreme example of repressive uses of the Internet?

•Do private corporations have an ethical responsibility to citizens living under authoritarian governments? If so, what form should corporate action take?

•Should Internet companies agree to the Communist Party’s censorship policies? Is such an agreement balanced by the benefits of greater access to the Internet by Chinese citizens?

•How can companies limit the harm done through the provision of Internet services?

465

China’s Web Junkies

![]() China’s Web Junkies

China’s Web Junkies

In Chapter 11, we note the central role that the Internet will play in our global future and raise questions about the local social and cultural effects. This video describes one way that China views those effects. In 2008, reports the video, China declared the prolonged recreational use of the Internet to be a clinical disorder similar to other behavioral addictions, such as gambling. The video examines a Chinese bootcamp-like center outside Beijing where youth are confined for treatment of “Internet addiction.” Teenagers (predominantly male) are brought to the center by their parents; there, they are subjected to a combination of therapy and military-like discipline for up to four months.

Thinking Geographically:

One scene in the video shows hundreds of Chinese youth gaming in an expansive, warehouse-sized Internet café. A camp patient describes how on one occasion he “stayed there for three days” before he was forced into treatment. How would you describe the geography of recreational Internet use shown in China in comparison with what you are familiar with in the United States? Think in terms of domestic versus public spaces. How might the geography of Internet access in China versus the United States influence the tensions between children and parents over excessive Internet use? If in the future China’s Internet access becomes more individualized (i.e., more domestic, less public), how might that alter Chinese perceptions of Internet addiction?

We have often emphasized the complexities of geographic variation under globalization. In the case of China’s approach to prolonged Internet use, what differences can you identify in comparison to other countries and regions? For example, no global medical consensus exists on Internet addiction as there is for, say, opium addiction. Do you think similar teenage behavior (e.g., anger toward parents, prolonged absence from the house) in Europe or the United States will be blamed in the future on Internet addiction as has happened in China? How would you account for the regional differences that can be identified?

Other critics point out that virtual communities do not have the defining qualities of geographic communities: communion among citizens, shared responsibilities, and civic duty. Communication across the Internet does not a community make. Nevertheless, people can use virtual communities to establish bonds that carry over into the real world. To keep things in historical perspective, we should remember that throughout the modern period, families and individuals have left their geographic communities and dispersed widely. However, these people have constructed social networks to maintain cultural and emotional ties with their geographic communities of origin. From this perspective, we might view the Internet as just another vehicle for maintaining those ties and preserving cultural identities (see Subject to Debate).