CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

11.5

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Identify likely future landscapes.

We can get some clue about the kind of cultural landscapes we might expect in the future and the future of existing cultural landscapes by observing the cultural landscape under globalization. Philip Kelly even speaks of “landscapes of globalization.” He is referring mostly to the urban, corporate architecture that has sprung up on every continent, replicating itself in city after city. Such homogenization is often resisted by local communities that hope to preserve existing cultural landscapes.

GLOBALIZED LANDSCAPES

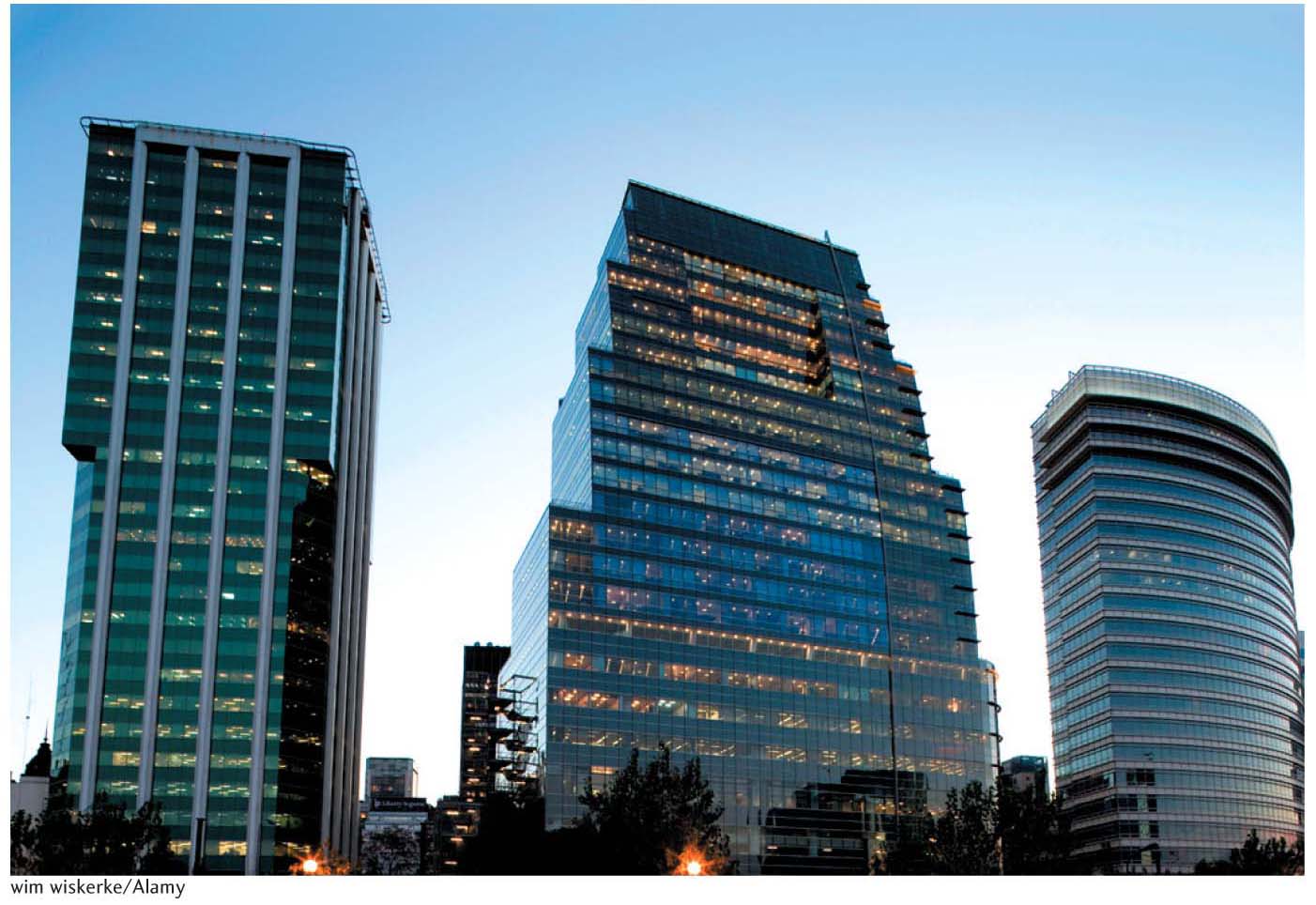

Geographer David Keeling sought visible evidence of globalization in the landscape of Buenos Aires, Argentina—the capital of a country that desperately wants to become enmeshed in the world economy but struggles, perhaps in vain, against its peripheral location. He found abundant evidence of “a homogenized landscape” of glass-and-steel corporate office towers, of luxury hotels and conference centers for the corporate power brokers of the world economy (Figure 11.21).

Clearly, urban landscapes—cityscapes—can serve as an index to the level and type of engagement with the globalization process. We have now begun witnessing the diffusion of California-style suburban housing tracts to affluent regions of India. Still, Keeling notes, these homogenizing processes are neither omnipresent nor omnipotent. Certain other Latin American capitals—such as Quito, Ecuador; La Paz, Bolivia; and Havana, Cuba—reveal minimal global influences in their cityscapes. Given the improbability of a global culture, visible differences among cities seem likely to persist. Moreover, people all over the world value their cultural landscapes, whether as visual reminders of their heritage or as lucrative attractions in the global tourism industry, and will thus want to preserve them. Landscape and place still matter in a globalizing world.

STRIVING FOR THE UNIQUE

Urban landscapes in the age of globalization reveal another element: the enduring spirit of place. One city after another has preserved or erected some building or monument so unique as to be a symbol or icon of that particular city. When you see a photograph of this structure, you know at once where it is located (Figure 11.22). Television journalists often stand in front of such visible icons to prove to viewers that they are actually reporting on location. Examples would include the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, the arch linking east and west in St. Louis, the Space Needle in Seattle, and the Eiffel Tower in Paris. True, many or most of these icons predate the era of globalization, but that is not the issue. Rather, their retention and protection offer the relevant message. In the 1960s, the city of Copenhagen restored Nyhavn (New Harbor), then a derelict seventeenth-century canal, into one of the most visually striking and instantly recognizable historical ports in the world (Figure 11.23). The Kremlin walls in Moscow may retain few if any of their original red bricks, as they fall victim to weathering and are replaced, but the structure is renewed and endures as a symbol of the city.

482

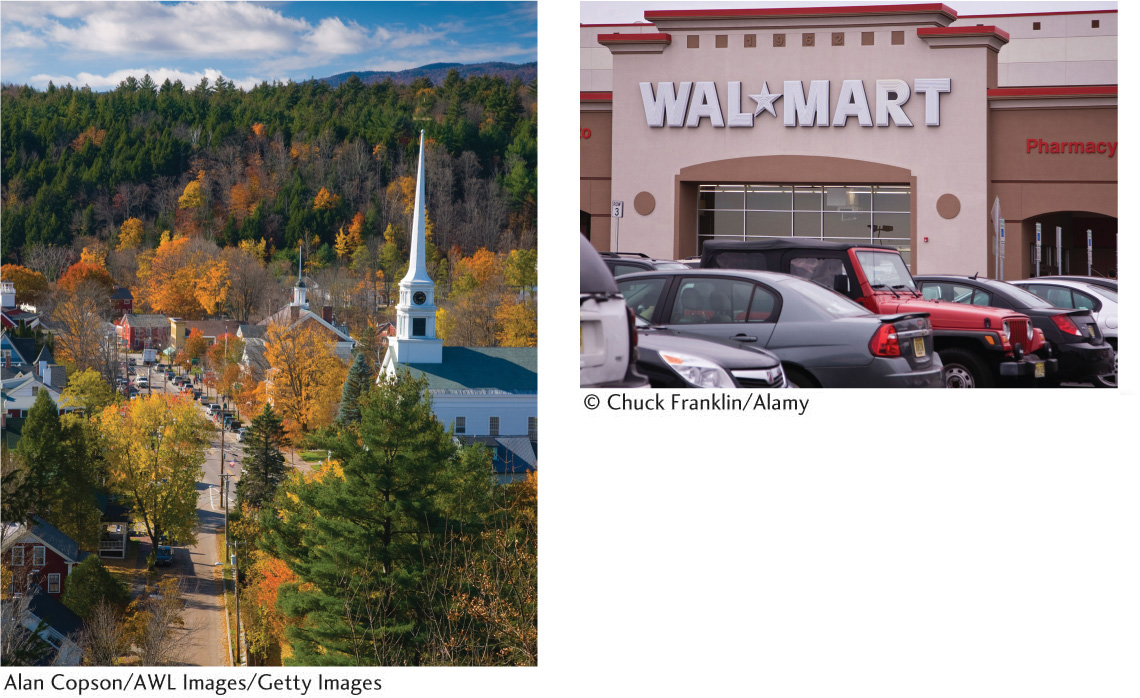

Neolocalism is the desire evident in many local communities to embrace the uniqueness and authenticity of place. Governments and electorates at all levels—from local to national—have a far greater say about globalization than one might imagine. A backlash against chain stores and conformity can find strength in local ordinances. A community can actually prevent McDonald’s or Walmart from establishing outlets. Neolocalism, then, pits the cultural power of place against the economic power of globalization.

neolocalism

The desire to re-embrace the uniqueness and authenticity of place, in response to globalization.

WAL-MARTIANS INVADE TREASURED LANDSCAPE!

Local communities and their governments attempt to preserve cultural landscapes in numerous ways. Zoning laws, architectural guidelines, minimum lot-size requirements, building codes, and conservation easements can all be used to maintain the distinct character of landscapes. At the global scale, we have World Heritage Sites, places that the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has deemed to be of such cultural significance that they should be given international protection. The temples at Angkor Wat in Cambodia (Figure 11.24) and the “Old Stone Town” on Zanzibar Island, Tanzania, are two examples of the hundreds of UNESCO World Heritage Sites worldwide.

483

Globalizing processes are putting new pressures on cultural landscapes. Often small community groups and town governments are pitted against powerful transnational corporations whose investment choices can profoundly transform a landscape. The phenomenal expansion of Walmart Stores, Inc., is an often cited example of how small-town landscapes are transformed by corporate investment. The biggest impact is the “hollowing out” of small-town main streets. Owner-run small businesses cannot compete with the giant retailer and soon have to lock their doors. Since “big box stores” such as Walmart are typically located outside of city centers, the old downtowns are turned into empty shells.

Some communities have welcomed Walmart and others have tried hard to keep out the chain. Perhaps the most novel opposition campaign was conducted in Vermont. In a confrontation that author Barbara Ehrenreich labeled “Earth People vs. Wal-Martians,” the National Trust for Historic Preservation declared the entire state of Vermont to be an endangered landscape. Vermont is the only state ever to make the list of endangered historic places, which generally comprise individual buildings and historic urban districts. According to the National Trust, building more supersized Walmart stores in Vermont would degrade the state’s “sense of place.” The National Trust had employed a similar strategy in 1993, which forced Walmart to build stores more appropriate to Vermont’s landscape (Figure 11.25).

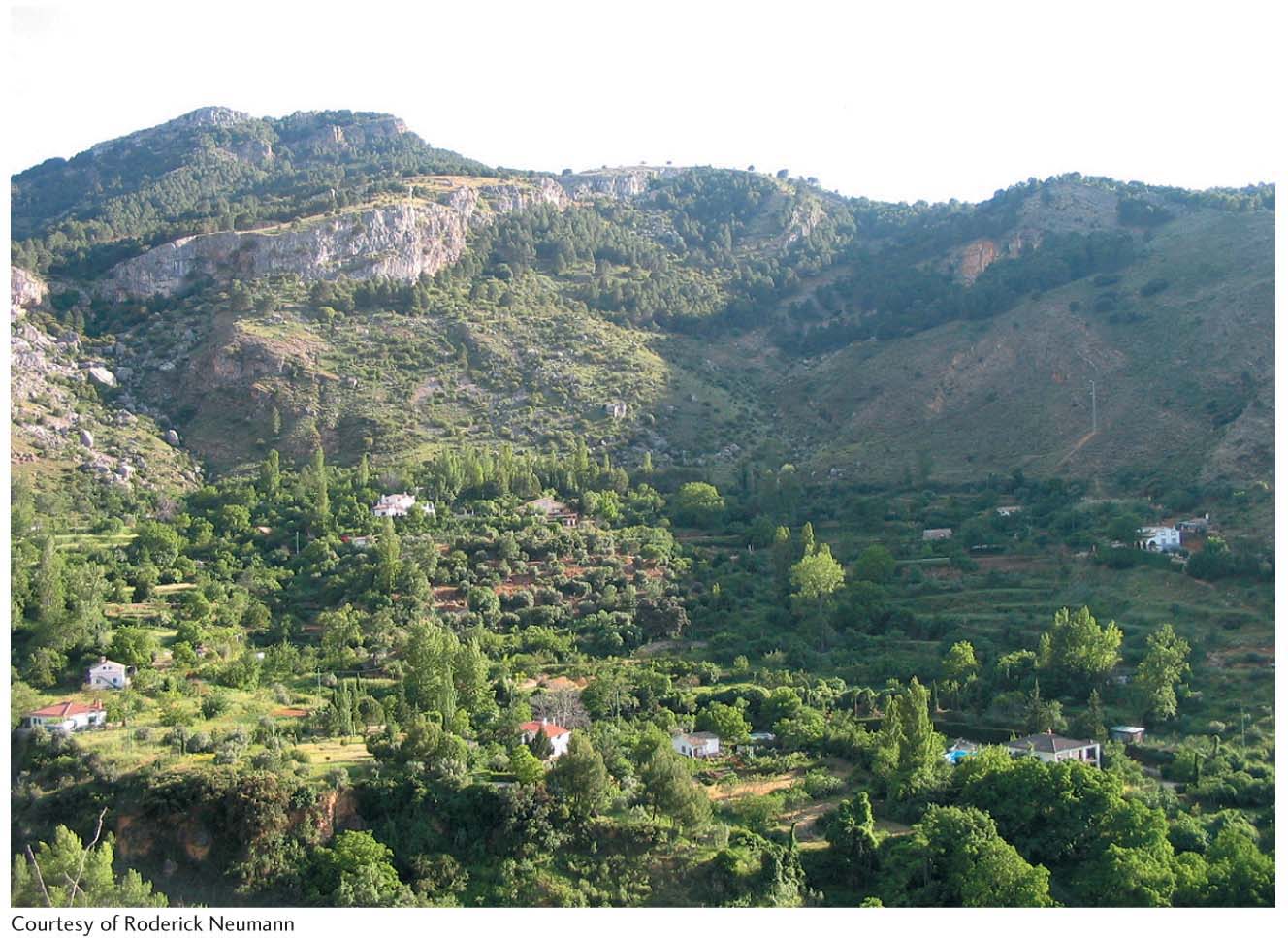

PROTECTING EUROPE’S RURAL LANDSCAPE

Another aspect of globalization, the drive to eliminate territorial barriers to the free trade of commodities, threatens rural landscapes in Europe. The fear is that cheap food imports will put small farmers out of business, which in turn will lead to the demise of treasured rural landscapes (Figure 11.26). European farmers and their national and EU representatives have argued that agriculture is not solely about food production—that it performs multiple functions, such as maintaining cultural landscapes and providing environmental services. Geographer Gail Hollander has observed that farmers and their advocates are using what they call agriculture’s “multifunctionality” to gain exemptions from the WTO’s strict rules on free trade. The exemptions are warranted, they argue, in order to preserve the character of cultural landscapes that agriculture supports. Hollander concludes that multifunctionality could be used to preserve the landscapes of a few communities in Europe or, in stronger form, to challenge the very logic of the WTO’s rules on the global trade of agricultural products. Given their symbolic value, the preservation of cultural landscapes may be a key tool used to slow or mitigate globalization’s homogenizing effects.

NO ANALOG LANDSCAPE FUTURES

The trends in fossil fuel consumption all point to a global atmosphere with carbon dioxide concentrations far beyond what the human species has ever experienced. The consensus among physical geographers and other climate scientists is that higher carbon dioxide concentrations are closely correlated with rising global temperatures. How high and how fast of a temperature rise remains subject to debate, but the effects on cultural landscapes are already observable. From these observations, we can speculate about landscape futures, albeit with no analogs in past landscapes to guide us.

484

Rural geographer Michael Woods surveyed a range of studies in an effort to forecast rural futures under conditions of global warming. Perhaps the most straightforward impact will be a latitudinal movement of agricultural landscapes northward in the Northern Hemisphere. As temperatures rise, growing seasons will lengthen, so we will see a movement of the various belts—Wheat Belt, Corn Belt, Cotton Belt—northward. More complex climate effects imply more complex outcomes. For example, climate models show local and regional rainfall patterns shifting under global warming. Increased drought occurrence may lead to the spread of irrigation, but only where local cultural and political institutions can manage the needed levels of organization and cooperation. Woods observes that in some cases climate change is exacerbating land abandonment and accelerating rural-to-urban urban migration, leading to an emptying out of rural landscapes. Efforts to expand wind power and reduce fossil fuel consumption have produced local conflicts over the placement of wind generators that disrupt the vision of idyllic rural landscapes. These examples merely hint at the complexity of forces shaping rural landscape futures.

485

Urban landscape futures are similarly confronted by the environmental changes wrought by global warming. Most critically for cities will be sea-level rise. Superstorm Sandy provided a glimpse of what the future holds for coastal cities when it hit lower Manhattan on October 28, 2012, bringing a record tidal surge of nearly 14 feet. The current trend indicates that sea level is rising faster than in past centuries and the rate of rise appears to be accelerating. In 2013 geographers Susan Cutter and William Soleki convened a panel of experts to report on the urban impacts of climate change for the U.S. National Climate Assessment and Development Advisory Committee. Sea-level rise, they observe, has the direct effect of coastal flooding, but the indirect effects, such as power outages and damaged sewer and water systems, extend well beyond flooded areas. A team of researchers recently projected the likely exposure to sea-level rise in 2070 of the world’s largest port cities. Worldwide, they expect that 150 million people and over $3000 billion in property will be exposed to damaging storm surges. A wide range of responses to sea-level rise will drastically alter coastal urban landscape futures. Most dramatic will be population migration inland. In the wake of Sandy, for example, state governments are considering the abandonment of coastal zones for housing and the implementation of open-space green belts at the seashore to reduce the exposure of life and property. A wide variety of floating structures are now appearing on urban development plans. Infrastructure changes, including raised roadways, elevated power systems, and coastal protection structures such as breakwaters, dikes, and floodgates, are in the works (Figure 11.27). The future landscapes of coastal cities will no doubt include a wide variety of new visual elements.