A Cultural Approach

xx

CHAPTER 1

HUMAN GEOGRAPHY

A Cultural Approach

Why is it difficult for most of us to interpret this image as a map?

Navigational chart representing a portion of the Marshall Islands in Micronesia.

(Courtesy of Roderick Neumann)

Go to “Seeing Geography” to learn more about this image.

1

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

▪1.1

Identify and define different types of regions.

▪1.2

Define mobility and name five types of diffusion.

▪1.3

Describe globalization and explain its importance to cultural geography.

▪1.4

Define the different models of nature-culture relations.

▪1.5

Explain the concept of cultural landscape.

Most of us are born geographers. We are curious about the distinctive character of places and peoples. We think in terms of territory and space. Take a look outside your window right now. The houses and commercial buildings, streets and highways, gardens and lawns all tell us something interesting and profound about who we are as a culture. If you travel down the road, or on a jet to another region or country, that view outside your window will change, sometimes subtly, sometimes drastically. Our geographical imaginations will push us to look and think and begin to make sense of what is going on in these different places, environments, and landscapes. It is this curiosity about the world—about how and why it is structured the way it is, what it means, and how we have changed it and continue to change it—that is at the heart of human geography. You are already geographers; we hope that our book will make you better ones.

If all places on Earth were identical, we would not need geography, but each is unique. Every place, however, does share characteristics with other places. Geographers define the concept of region as a grouping of similar places or of places with similar characteristics. The existence of different regions endows the Earth’s surface with a mosaiclike quality. Geography as an academic discipline is an outgrowth of both our curiosity about lands and peoples other than our own and our need to come to grips with the place-centered element within ourselves. When professional, academic geographers consider the differences and similarities among places, they want to understand what they see. They first find out exactly what variations exist among regions and places by describing them as precisely as possible. Then they try to decide what forces made these areas different or alike. Geographers ask what? where? why? and how?

region

A grouping of like places or the functional union of places to form a spatial unit.

2

Our natural geographical curiosity and intrinsic need for identity were long ago reinforced by pragmatism, the practical motives of traders and empire builders who wanted information about the world for the purposes of commerce and conquest. This concern for the practical aspects of geography first arose thousands of years ago among the ancient Greeks, Romans, Mesopotamians, and Phoenicians, the greatest traders and empire builders of their times. They cataloged factual information about locations, places, and products. Indeed, geography is a Greek word meaning literally “to describe the Earth.” Not content merely to chart and describe the world, these ancient geographers soon began to ask questions about why cultures and environments differ from place to place, initiating the study of what today we call geography.

geography

The study of spatial patterns and of differences and similarities from one place to another in environment and culture.

WHAT IS A CULTURAL APPROACH TO HUMAN GEOGRAPHY?

Human geography forms one part of the discipline of geography, complementing physical geography (which deals with the natural environment). Human geography examines the relationships between people and the places and spaces in which they live using a variety of scales ranging from the local to the global. Human geographers explore how these relationships create the diverse spatial arrangements that we see around us, arrangements that include homes, neighborhoods, cities, nations, and regions. A cultural approach to the study of human geography implies an emphasis on the meanings, values, attitudes, and beliefs that different groups of people around the world lend to and derive from places and spaces. To understand the scope of a cultural approach to human geography, we must first discuss the various meanings of culture.

human geography

The study of the relationships between people and the places and spaces in which they live.

culture

A total way of life held in common by a group of people, including such learned features as speech, ideology, behavior, livelihood, technology, and government; or the local, customary way of doing things — a way of life; an ever-changing process in which a group is actively engaged; a dynamic mix of symbols, beliefs, speech, and practices.

Culture is a very complex term and there are many different definitions. In this book, we think of culture in two ways. In one sense, we use culture to refer to a variety of human behavioral traits and beliefs (e.g., marriage rites), which we define as learned, as opposed to innate, or inborn.

Defined in this way, culture involves a means of communicating these learned beliefs, practices, memories, perceptions, and values that serves to shape individual and collective behaviors. As geographers, we tend to be interested in how these various aspects of culture shape, and take shape in, particular places, environments, and landscapes.

Culture is not a static, fixed phenomenon, and it does not always govern its members. Rather, as geographers Kay Anderson and Fay Gale put it, “Culture is a process in which people are actively engaged.” Individuals can and do change cultural practices, those social activities and interactions—ranging from religious rituals to food preferences to clothing—that collectively distinguish group identity. This understanding of culture recognizes that ways of life constantly change and that tensions between opposing views are usually present.

cultural practices

The social activities and interactions— ranging from religious rituals to food preferences to clothing—that collectively distinguish group identity.

3

Throughout the book, we will also use culture in the second sense to refer to a distinctive group identity (e.g., Navaho culture). By this we mean that collectively shared beliefs, practices, language, technologies, and so forth produce characteristic ways of life for groups of people. Thus, we speak of cultures in the plural. Geographers have historically thought in terms of both categories of cultures (e.g., tribal, urban) and also specific cultures associated with specific places and regions (e.g., Tuareg camel pastoralists). There are an almost infinite number of ways of defining human groups in cultural terms or of creating categories of cultures. Today we are accustomed to hearing about not only Tuareg culture or Navaho culture, but also hip-hop culture or gay culture. The now-familiar appeals to multiculturalism and cultural diversity reflect a growing appreciation of the complex, ongoing processes of cultural differentiation that are characteristic of human society.

Cultures, however we may categorize and label them, are never internally homogeneous because individual humans never think or behave in exactly the same manner. Sometimes internal differences can be so great that groups experience a fission that results in the formation of new and distinct cultures. Historically, such fissions were often associated with mass human migrations to new lands and environments. Neither are cultural groups consistent across time and space. Cultures are defined as much by dynamism and change as by fixity and stability. In short, we follow Anderson and Gale in taking the view of culture as a process rather than as a thing.

A cultural approach to human geography, then, studies the relationships among space, place, environment, and culture. It examines the ways in which culture is expressed and symbolized in the landscapes we see around us, including homes, commercial buildings, roads, agricultural patterns, gardens, and parks. It analyzes the ways in which language, religion, the economy, government, and other cultural phenomena vary or remain constant from one place to another, and provides a perspective for understanding how people function spatially and identify with place and region (Figure 1.1).

4

In seeking explanations for cultural diversity and place identity, geographers consider a wide array of factors that cause this diversity. Some of these involve the physical environment: terrain, climate, natural vegetation, wildlife, variations in soil, and the pattern of land and water. Because we cannot understand a culture removed from its physical setting, human geography offers not only a spatial perspective but also an ecological one.

physical environment

All aspects of the natural physical surroundings, such as climate, terrain, soils, vegetation, and wildlife.

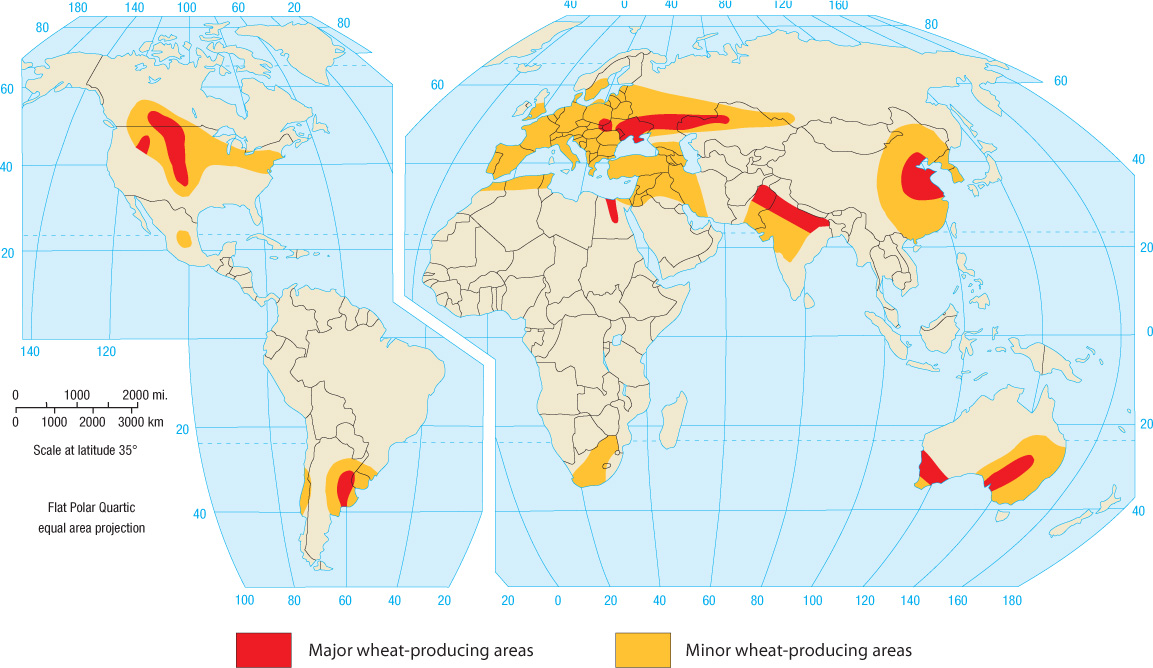

Many complex forces are at work on cultural phenomena, and all of them are interconnected in very complicated ways. The complexity of the forces that affect culture can be illustrated by an example drawn from agricultural geography: the distribution of wheat cultivation in the world. If you look at Figure 1.2, you can see important areas of wheat cultivation in Australia but not in Africa, in the United States but not in Chile, in China but not in Southeast Asia. Why does this spatial pattern exist? Partly, it results from environmental factors such as climate, terrain, and soils. Some regions have always been too dry for wheat cultivation. The land in others is too steep or infertile. Indeed, strong correlation exists between wheat cultivation and midlatitude climates, level terrain, and good soil.

Still, we should not place exclusive importance on such physical factors. People can modify the effects of climate through irrigation; the use of hothouses; or the development of new, specialized strains of wheat. They can conquer slopes by terracing, and they can make poor soils productive with fertilization. For example, farmers in mountainous parts of Greece traditionally wrested an annual harvest of wheat from tiny terraced plots where soil had been trapped behind hand-built stone retaining walls. Even in the United States, environmental factors alone cannot explain the curious fact that major wheat cultivation is concentrated in the semiarid Great Plains, some distance from states such as Ohio and Illinois, where the climate for growing wheat is better. Human geographers know that wheat has to survive in a cultural environment as well as a physical one.

5

Ultimately, agricultural patterns cannot be explained by the characteristics of the land and climate alone. Many factors complicate the distribution of wheat, including people’s tastes and traditions. Food preferences and taboos, often backed by religious beliefs, strongly influence the choice of crops to plant. Where wheat bread is preferred, people are willing to put great efforts into overcoming physical surroundings hostile to growing wheat. They have even created new strains of wheat, thereby decreasing the environment’s influence on the distribution of wheat cultivation. Other factors, such as public policies, can also encourage or discourage wheat cultivation. For example, tariffs protect the wheat farmers of France and other European countries from competition with more efficient American and Canadian producers.

This is by no means a complete list of the forces that affect the geographical distribution of wheat cultivation. The distribution of all cultural elements is a result of the constant interplay of diverse factors. Human geography is the discipline that seeks such explanations and understandings.

HOW TO UNDERSTAND HUMAN GEOGRAPHY

Generally speaking, geographers have adopted three different perspectives in studying and understanding the complexity of the human mosaic. Each of these perspectives brings a different emphasis to studying the diversity of human patterns on the Earth.

Spatial Models Some geographers seek patterns and regularities amid the complexity and apply the scientific method to the study of people. Emulating physicists and chemists, they devise theories and seek regularities or universal spatial principles that apply across cultural lines, explaining all of humankind. These principles ideally become the basis for laws of human spatial behavior. Space—a term that refers to an abstract location on a map—is the word that perhaps best connotes this approach to cultural geography (see Doing Geography, in the Conclusion).

space

Connotes the objective, quantitative, theoretical, modelbased, economics-oriented type of geography that seeks to understand spatial systems and networks through application of the principles of social science.

Social scientists face a difficult problem because, unlike physical scientists, they cannot limit the effects of diverse factors by running experiments in controlled laboratories. One solution to this problem is the technique known as model building. Aware that many causal forces are involved in the real world, they set up artificial situations to focus on one or more potential factors. That is, they abstract a limited set of factors from the complexities of social life in an effort to uncover fundamental spatial patterns and forms.

model

An abstraction, an imaginary situation, proposed by geographers to simulate laboratory conditions so they can isolate certain causal forces for detailed study.

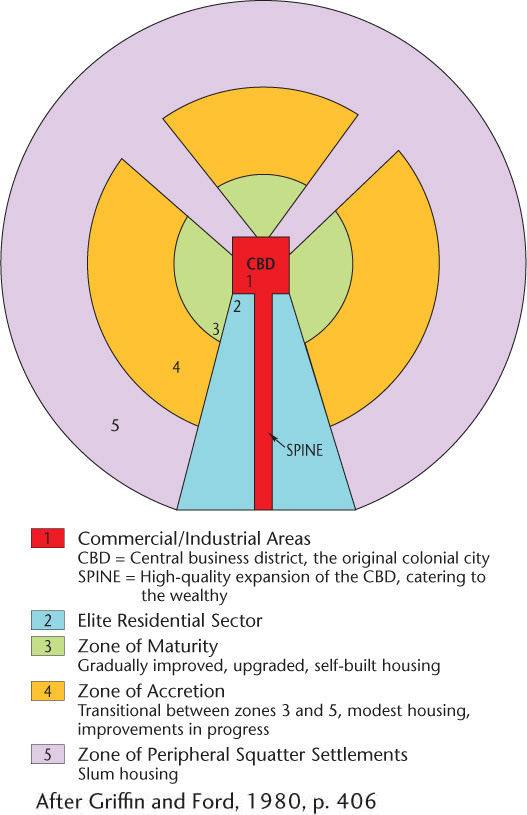

Torsten Hägerstrand’s diagrams of different ways in which ideas and people move from one place to another are examples of spatial models. Some model-building geographers devise culture-specific models to describe and explain certain facets of spatial behavior within specific cultures. They still seek regularities and spatial principles but within the bounds of individual cultures. For example, several geographers proposed a model for Latin American cities in an effort to stress similarities among them and to understand why cities are formed the way they are (Figure 1.3). Obviously, no actual city in Latin America conforms precisely to their uncomplicated geometric plan. Instead, as in all model building, they deliberately generalized and simplified so that an urban type could be recognized and studied. The model will look strange to a person living in a city in the United States or Canada, for it describes a very different kind of urban environment, based in another culture.

Sense of Place Other geographers seek to understand the uniqueness of each region and place. Just as space identifies the perspective of the model-building geographer, place is the key word connoting this more humanistic view of geography. The geographer Yi-Fu Tuan coined the word topophilia, literally “love of place,” to describe the characteristic of people who exhibit a strong sense of place and the geographers who are attracted to the study of such places and peoples. Geographer Edward Relph tells us that “to be human is to have and know your place” in the geographical sense. This perspective on cultural geography values subjective experience over objective scientific observation. It focuses on understanding the complexity of different cultures and how those cultures give meaning to and derive meaning from particular places. Many geographers are interested in understanding how and why certain places continue to evoke strong emotions in people, even though those people may have little direct connection with those places.

place

Connotes the subjective, idiographic, humanistic, culturally oriented type of geography that seeks to understand the unique character of individual regions and places, rejecting the principles of science as flawed and unknowingly biased.

6

Denis Cosgrove, for example, studied why Venice, Italy, continues to stir people’s imaginations—people as diverse as tourists from Japan and farmers from Iowa—despite the fact that the city hasn’t held any political or economic power in hundreds of years and that the cultures out of which it was formed have long since ceased to exist. Such is the symbolic importance of Venice that in the 1960s millions of dollars came from all around the world in a massive international campaign to save the city from decay and flooding. Similar successful campaigns in other places led the United Nations in 1975 to establish a program to coordinate efforts to identify, catalog, and protect sites of worldwide significance. Known as World Heritage Sites, these are places (e.g., buildings, cities, forests, lakes, deserts, archeological ruins) that the UN’s International Heritage Programme judges to possess outstanding cultural or natural importance to the common heritage of humanity. Venice was among the earliest of the UN’s additions to its list, which numbered 981 sites in 2014. The designation has served to draw even more international tourists to Venice, which now receives roughly 50 times as many visitors per year as the number of permanent residents in the historic city.

World Heritage Sites

Places (e.g., buildings, cities, forests, lakes, deserts, archeological ruins) that the UN’s International Heritage Programme judges to possess outstanding cultural or natural importance to the common heritage of humanity.

Some cultural geographers, however, are interested in the opposite kind of places—ordinary places. They ask how and why people become attached to and derive meaning from their local neighborhoods or communities, and explore how those meanings can often come into conflict with each other. Many of the debates that you learn about in newspapers or online—debates on the construction of a new high-rise building or the location of a highway, for example—can only be understood by examining the meanings and values different groups of people give to and derive from particular places.

7

Power and Ideology Cultures are rarely, if ever, homogeneous. Often certain groups of people have more power in society, and their beliefs and ways of life dominate and are considered the norm, whereas other groups of people with less power may participate in alternative cultures. These divisions are often based on gender, economic class, racial categories, ethnicity, or sexual orientation. The social hierarchies that result are maintained, reinforced, and challenged through many means. Those means can include such things as physical violence, but often social hierarchies are maintained in ways far more subtle.

For example, some geographers study ideology—a set of dominant ideas and beliefs—in relationship to place, environment, and landscape in order to understand how power works culturally. For instance, most nations maintain a set of powerful beliefs about their relationships to the land, some holding to the idea that a deep and natural connection exists between a particular territory and the people who have inhabited it. These ideas often form part of a national identity and are expressed so routinely in poems, music, laws, and rituals that people accept these ideas as truths. Many American patriotic songs, for example, express the idea that the country naturally spreads from “sea to sea.” Yet, immigrants to that culture and country, and people who have been marginalized by that culture, may hold very different ideas of identity with the land. Native Americans have claims to land that far predate those of the U.S. government, and they would argue against an American national identity that includes a so-called natural connection to all the land between the Atlantic and the Pacific. Uncovering and analyzing the connections between ideology and power, then, are often integral to the geographer’s task of understanding the diversity within a culture.

These different approaches to thinking about human geography are both necessary and healthy. These groups ask different questions about place and space; not surprisingly, they often obtain different answers. The model-builders tend to minimize diversity through their search for universal causal forces; the humanists examine diversity among cultures and strive to understand the unique; those who look to power and ideology focus on diversity and contestation within cultures. All lines of inquiry yield valuable findings. We present all these perspectives throughout Contemporary Human Geography.

THEMES IN HUMAN GEOGRAPHY

Our study of the human mosaic is organized around five geographical concepts or themes: region, mobility, globalization, nature-culture, and cultural landscape. We use these themes to organize the diversity of issues that confront human geography and have selected them because they represent the major concepts that human geographers discuss. Each of them stresses one particular aspect of the discipline, and even though we have separated them for purposes of clarity, it is important to remember that the concepts are related to each other. When discussing the theme of mobility, for example, we will inevitably bring up issues related to globalization, and vice versa. These themes give a common structure to each chapter and are stressed throughout the book.