REGION

1.1

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Identify and define different types of regions.

Phrased as a question, the theme of region could be “How are people and their traits grouped or arranged geographically?” Places and regions provide the essence of geography. How and why are places alike or different? How do they mesh together into functioning spatial networks? How do their inhabitants perceive them and identify with them? These are central geographical questions. A region, then, is a geographical unit based on characteristics and functions of culture. Geographers recognize three types of regions: formal, functional, and vernacular.

8

FORMAL REGIONS

A formal region is an area inhabited by people who have one or more traits in common, such as language, religion, or a system of livelihood. It is an area, therefore, that is relatively homogeneous with regard to one or more cultural traits. Geographers use this concept to map spatial differences throughout the world. For example, an Arabic-language formal region can be drawn on a map of languages and would include the areas where Arabic is the native language of the majority of the population. Similarly, a wheat-farming formal region would include the parts of the world where wheat is a predominant crop (look again at Figure 1.2).

formal region

A cultural region inhabited by people who have one or more cultural traits in common.

The examples of Arabic speech and of wheat cultivation represent the concept of formal region at its simplest level. Each is based on a single cultural trait. More commonly, formal regions depend on multiple related traits (Figure 1.4). Thus, an Inuit (Eskimo) culture region might be based on language, religion, economy, social organization, and type of dwellings. The region would reflect the spatial distribution of these five Inuit cultural traits. Districts in which all five of these traits are present would be part of the culture region.

Formal regions are the geographer’s somewhat subjective creations. No two cultural traits have the same distribution, and the territorial extent of a culture region depends on what and how many defining traits are used. Why five Inuit traits, not four or six? Why not foods instead of (or in addition to) dwelling types? Consider, for example, Greeks and Turks, who differ in language and religion. Formal regions defined on the basis of speech and religious faith would separate these two groups. However, Greeks and Turks hold many other cultural traits in common. Both groups are monotheistic, worshipping a single god. In both groups, male supremacy and patriarchal families are the rule. Both enjoy certain traditional foods, such as shish kebab. Whether or not Greeks and Turks are placed in the same formal region or in different ones depends entirely on how the geographer chooses to define the region. That choice, in turn, depends on the specific purpose of research or teaching that the region is designed to serve. Thus, an infinite number of formal regions can be created. It is unlikely that any two geographers would use exactly the same distinguishing criteria or place cultural boundaries in precisely the same location.

9

The geographer who identifies a formal region must locate borders. Because cultures overlap and mix, such boundaries are rarely sharp, even if only a single cultural trait is mapped. For this reason, we find border zones rather than lines. These zones broaden with each additional trait considered because no two traits have the same spatial distribution. As a result, instead of having clear borders, formal regions reveal a center or core where the defining traits are all present. Moving away from the central core, the characteristics weaken and disappear. Thus, many formal regions display a core-periphery pattern. This refers to a situation where a region can be divided into two sections: one near the center where the particular attributes that define the region (in this case, language and religion) are strong, and other portions of the region farther away from the core, called the periphery, where those attributes are weaker.

border zones

The areas where different regions meet and sometimes overlap.

core-periphery

The tendency of both formal and functional culture regions to consist of a core or node, in which defining traits are purest or functions are headquartered, and a periphery that is tributary and displays fewer of the defining traits.

In a real sense, then, the human world is chaotic and undergoing constant change. No matter how closely related two elements of culture seem to be, careful investigation always shows that they do not cover exactly the same area. This is true regardless of the degree of detail involved. What does chaos and change mean to the human geographer? First, it tells us that every cultural trait is spatially unique and that the explanation for each spatial variation differs in some degree from all others. Second, it means that culture changes continually throughout an area and that every inhabited place on Earth has a unique combination of cultural features. No place is exactly like another.

Does this cultural uniqueness of each place prevent geographers from seeking explanatory theories? Does it doom them to explaining each locale separately? The answer must be no. The fact that no two hills or rocks, no two planets or stars, no two trees or flowers are identical has not prevented geologists, astronomers, and botanists from formulating theories and explanations based on generalizations. So it is with human geography.

FUNCTIONAL REGIONS

The hallmark of a formal region is cultural homogeneity. By contrast, a functional region need not be culturally homogeneous; instead, it is an area that has been organized to function politically, socially, or economically as one unit. A city, an independent state, a precinct, a church diocese or parish, a trade area, a farm, and a Federal Reserve Bank district are all examples of functional regions. Functional regions have nodes, or central points where the functions are coordinated and directed. Examples of such nodes are city halls, national capitals, precinct voting places, parish churches, factories, and banks. In this sense, functional regions also possess a core-periphery configuration, in common with formal regions.

functional region

A cultural area that functions as a unit politically, socially, or economically.

node

A central point in a functional culture region where functions are coordinated and directed.

Many functional regions have clearly defined borders. A metropolitan area is a functional region that includes all the land under the jurisdiction of a particular urban government (Figure 1.5). The borders of this functional region may not be so apparent from a car window, but they will be clearly delineated on a regional map by a line distinguishing one jurisdiction from another. Similarly, each state in the United States and each Canadian province is a functional region, coordinated and directed from a capital, with government control extended over a fixed area with clearly defined borders.

10

Not all functional regions have fixed, precise borders, however. A good example is a daily newspaper’s circulation area. The node for the paper would be the plant where it is produced. Every morning, trucks move out of the plant to distribute the paper throughout the city and surrounding suburbs and countryside. The sales territory of one newspaper may thus overlap with the sales territories of other city newspapers, making boundaries difficult to define. Take, for example, the Kansas City Star, which is distributed in 33 counties in Kansas and Missouri. To the east, the paper’s distribution overlaps with that of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, which has a much larger distribution area including Kansas City itself.

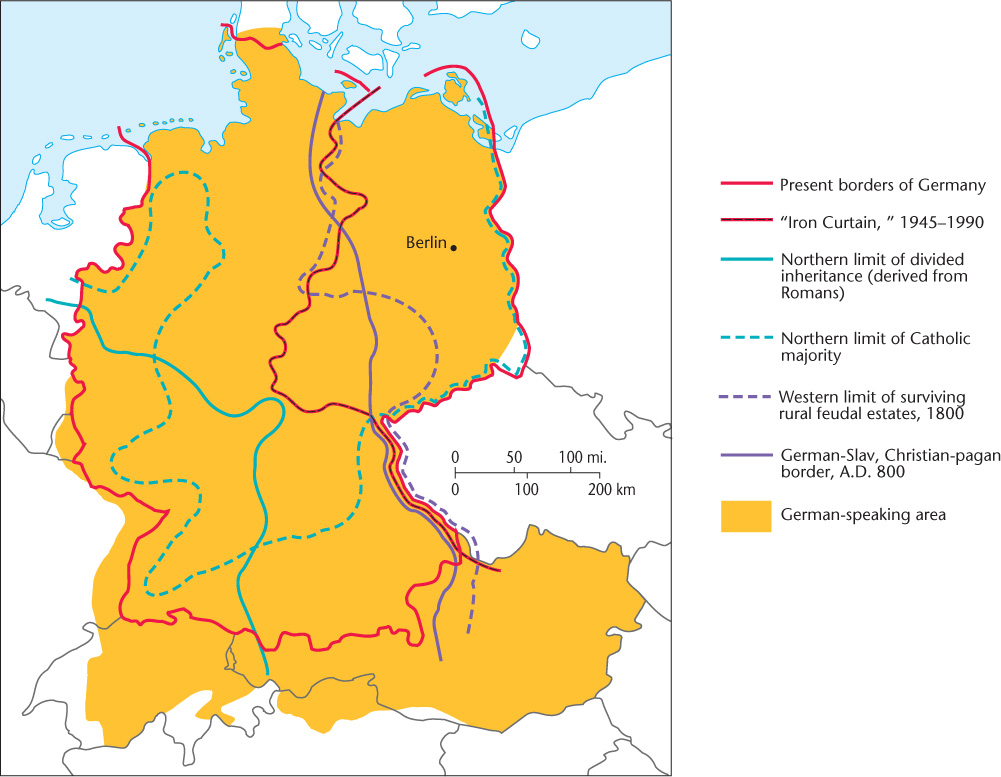

Functional regions generally do not coincide spatially with formal regions, and this disjuncture often creates problems for the functional region. Germany provides an example (Figure 1.6). As an independent state, Germany forms a functional region. Language provides a substantial basis for political unity. However, the formal region of the German language extends beyond the political borders of Germany. It includes part or all of eight other independent states. More important, numerous formal regions have borders cutting through German territory. Some of these have endured for millennia, causing differences among northern, southern, eastern, and western Germans. These contrasts make the functioning of the German state more difficult and help explain why Germany has been politically fragmented more often than unified.

VERNACULAR REGIONS

A vernacular region is one that is perceived to exist by its inhabitants, as evidenced by the widespread acceptance and use of a special regional name. We might think of vernacular regions as the most democratic type of all. Vernacular regions are named and their boundaries imagined through popular consensus. (Indeed, the term “popular region” is sometimes used in a similar way.) Like old gospel or folk songs passed down over the years from one musician to another, it is often difficult to trace the precise origins of a vernacular regional designation. Typically, the name of a vernacular region first becomes widely known through a local newspaper column, popular song, blog site, or some other form of popular mass communication. The vernacular name then “sticks.” That is, it becomes widely adopted in everyday speech, if not in official documents.

vernacular region

A culture region perceived to exist by its inhabitants, based in the collective spatial perception of the population at large and bearing a generally accepted name or nickname (such as “Dixie”).

Some vernacular regions are based on physical environmental features. For example, there are many regions called simply “the valley.” Wikipedia lists more than 30 different regions in the United States and Canada referred to as such, places as varied as the Sudbury Basin in Ontario and the Lehigh Valley in Pennsylvania. In the 1980s, “the valley” became synonymous with the San Fernando Valley in Southern California and became associated with a type of landscape (suburban), person (a white, teenage girl, called the “valley girl”), and way of speaking (“valspeak”).

11

Other vernacular regions find their basis in economic, political, or historical characteristics. “Redneck Riviera” is a popular designation for the coastal area of the Florida panhandle, running from Panama City in the east to Pensacola and beyond in the west. “Redneck” is a term referring to politically conservative, working-class, rural culture in the United States. “Riviera” refers, ironically, to the affluent resort area of the French Mediterranean coast. Historically, the numerous military bases strung up and down the panhandle coastline propelled the region’s economy. The bases provided jobs, while the gentle climate, inexpensive real estate, and white sand beaches encouraged retired military personnel to put down roots. The politically conservative culture of military retirees combined with the remnants of rural southern vernacular speech and cuisine creates a distinctive beach vacation destination (Figure 1.7). In 1996 country-and-western singer Tom T. Hall released a song entitled “Redneck Riviera” that included the lyrics: “They got beaches of the whitest sand / Nobody cares if gramma’s got a tattoo.” The region’s local governments and chambers of commerce created an alternative designation for it, “Emerald Coast,” and have worked hard to eliminate all references to the Redneck Riviera. In 2010 the Gulf Shores, Alabama, city government even passed a prohibitive ordinance when a television production company scouted the town as a location for a proposed reality TV show to be called Redneck Riviera. City ordinances aside, we would be willing to wager a week’s salary that far more Floridians can identify the vernacular Redneck Rivera than can identify the officially sanctioned Emerald Coast.

12

Vernacular regions, like most regions, generally lack sharp borders, and the inhabitants of any given area may claim residence in more than one such region. They vary in scale from city neighborhoods to sizable parts of continents. At a basic level, a vernacular region grows out of people’s sense of belonging to and identification with a particular region. By contrast, many formal or functional regions lack this attribute and, as a result, are often far less meaningful for people. You’re more likely to hear people say “we’re fighting to preserve ‘the valley’ from further urban development” than to see people rally under the banner of “wheat-growing areas of the world”! Self-conscious regional identity can have major political and social ramifications.

Vernacular regions often lack the organization necessary for functional regions, although they may be centered around a single urban node, and they frequently do not display the cultural homogeneity that characterizes formal regions.