MOBILITY

1.2

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Define mobility and name five types of diffusion.

The concept of regions helps us see that similar or related sets of elements are often grouped together in space. Equally important in geography is understanding how and why these different cultural elements move through space and locate in particular settings. Regions themselves, as we have seen, are not stable but are constantly changing as people, ideas, practices, and technologies move around in space. Are there some patterns to these movements? These questions define our second theme, mobility.

mobility

The relative ability of people, ideas, or things to move freely through space.

One important way to study mobility is through the concept of diffusion. Diffusion can be defined as the movement of people, ideas, or things from one location outward toward other locations where these items are not initially found. Through the study of diffusion, the human geographer can trace how spatial patterns in culture emerged and evolved. After all, any culture is the product of almost countless innovations that spread from their points of origin to cover a wider area. Some innovations occur only once, and geographers can sometimes trace a cultural element back to a single place of origin. In other cases, independent invention occurs: the same or a very similar innovation is separately developed at different places by different peoples.

diffusion

The movement of people, ideas, or things from one location outward toward other locations.

independent invention

A cultural innovation developed in two or more locations by individuals or groups working independently.

13

TYPES OF DIFFUSION

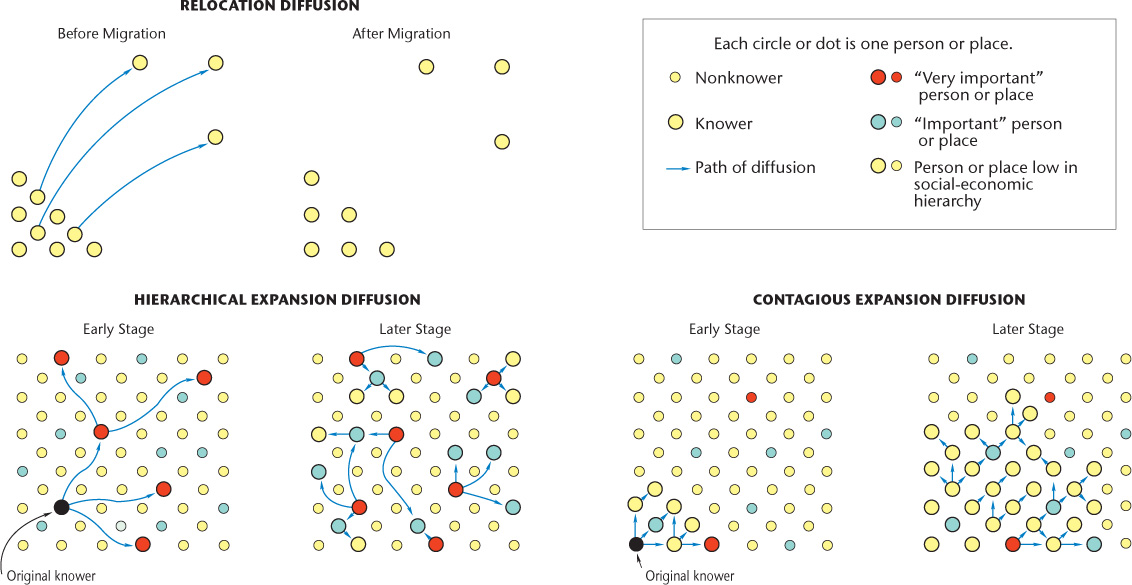

Examining spatial models developed by Hägerstrand, geographers recognize several different kinds of diffusion (Figure 1.8). Relocation diffusion occurs when individuals or groups with a particular idea or practice migrate from one location to another, thereby bringing the idea or practice to their new homeland. Religions frequently spread this way. An example is the migration of Christianity with European settlers who came to America. In expansion diffusion, ideas or practices spread throughout a population, from area to area, in a snowballing process, so that the total number of knowers or users and the areas of occurrence increase.

relocation diffusion

The spread of an innovation or other element of culture that occurs with the bodily relocation (migration) of the individual or group responsible for the innovation.

expansion diffusion

The spread of innovations within an area in a snowballing process, so that the total number of knowers or users becomes greater and the area of occurrence grows.

14

Expansion diffusion can be further divided into three subtypes. In hierarchical diffusion, ideas leapfrog from one important person to another or from one urban center to another, temporarily bypassing other persons or rural territories. We can see hierarchical diffusion at work in everyday life by observing the acceptance of new modes of dress or foods. For example, sushi restaurants originally diffused from Japan in the 1970s very slowly because many people were reluctant to eat raw fish. In the United States, the first sushi restaurants appeared in the major cities of Los Angeles and New York. Only gradually throughout the 1980s and 1990s did eating sushi become more common in the less urbanized parts of the country. By contrast, contagious diffusion involves the wavelike spread of ideas in the manner of a contagious disease, moving throughout space without regard to hierarchies.

hierarchical diffusion

A type of expansion diffusion in which innovations spread from one important person to another or from one urban center to another, temporarily bypassing other persons or rural areas.

contagious diffusion

A type of expansion diffusion in which cultural innovation spreads by person-to-person contact, moving wavelike through an area and population without regard to social status.

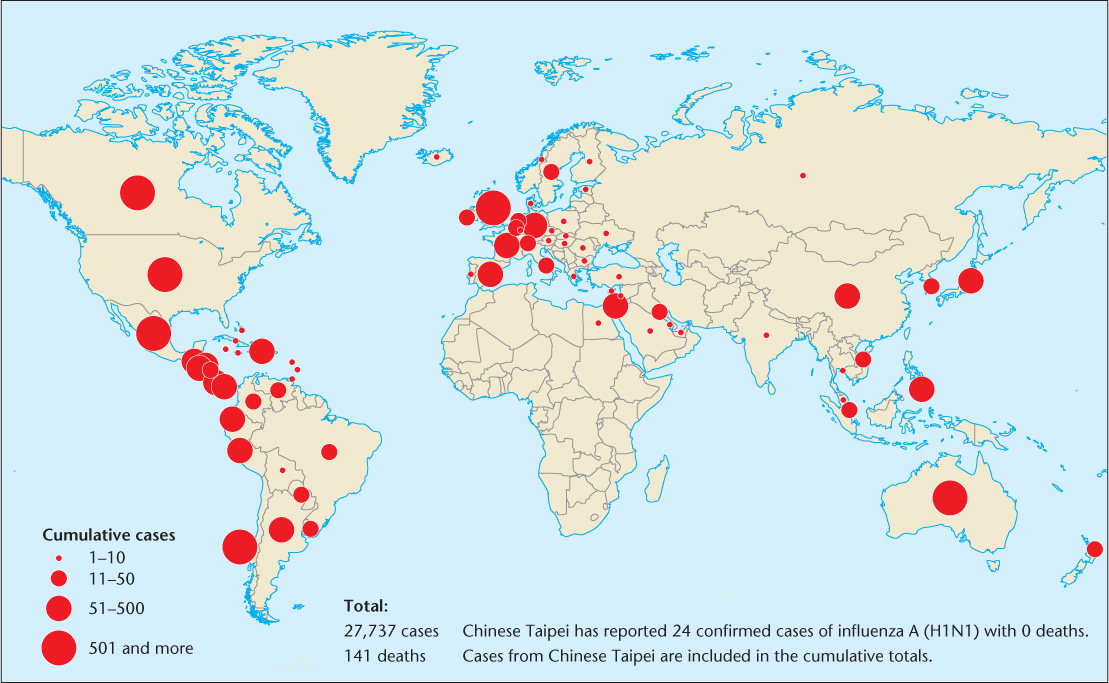

Hierarchical and contagious diffusion often work together. The 2009 influenza pandemic provides a sobering example of how these two types of diffusion can reinforce each other. A pandemic is a worldwide disease epidemic. In March 2009 Mexico announced that a new influenza virus strain, known as H1N1, had reached epidemic proportions in Mexico City. Many countries cut off airline traffic to Mexico in an attempt to inhibit the spread of H1N1. However, the virus had already been carried out of the country by air travelers. Through hierarchical diffusion it began to appear in major cities worldwide, and from there it spread through contagious diffusion to the countryside. China offers a clear example of this process. Chinese authorities first detected the virus in May 2009 in cities with international airports, where it remained confined for the next four months. Four to six months after the initial cases, H1N1 experienced its greatest geographic expansion as it spread across all of China (Figure 1.9).

Sometimes a specific trait is rejected but the underlying idea is accepted, resulting in stimulus diffusion. For example, early Siberian peoples domesticated reindeer only after exposure to the domesticated cattle raised by cultures to their south. The Siberians had no use for cattle, but the idea of domesticated herds appealed to them, and they began domesticating reindeer, an animal they had long hunted.

stimulus diffusion

A type of expansion diffusion in which a specific trait fails to spread but the underlying idea or concept is accepted.

If you throw a rock into a pond and watch the spreading ripples, you can see them become gradually weaker as they move away from the point of impact. In the same way, diffusion becomes weaker as a cultural innovation moves away from its point of origin. That is, diffusion decreases with distance. An innovation will usually be accepted most thoroughly in the areas closest to where it originates. Because innovations take increasing time to spread outward, time is also a factor. Acceptance generally decreases with distance and time, producing what geographers call time-distance decay. Modern mass media, however, along with relatively new technologies like the Internet and cell phones, have greatly accelerated diffusion, diminishing the impact of time-distance decay.

time-distance decay

The decrease in acceptance of a cultural innovation with increasing time and distance from its origin.

In addition to the gradual weakening or decay of an innovation through time and distance, barriers can retard its spread. Absorbing barriers completely halt diffusion, allowing no further progress. For example, many of us have become accustomed to using Google’s “Street View” mapping function that provides panoramic and zoom-in views from positions along many streets in the world. This technology allows users to plan everything from dining out to purchasing real estate. Street View, however, has raised privacy questions worldwide. Austria and Greece have chosen to prohibit the use of Street View technology within their borders because of privacy concerns. Among other effects on these countries, the ban will likely slow or halt the innovative uses of Street View now being explored in the visual arts.

absorbing barrier

A barrier that completely halts diffusion of innovations and blocks the spread of cultural elements.

15

Such examples aside, few absorbing barriers are effective or persist for long. More commonly, barriers are permeable, allowing part of the innovation wave to diffuse through them but acting to weaken or retard its continued spread. When a school board objects to students with tattoos or body piercings, the principal of a high school may set limits by mandating that these markings be covered by clothing. However, over time, those mandates may change as people get used to the idea of body markings. More likely than not, though, some mandates will remain in place. In this way, the principal and school board act as a permeable barrier to cultural innovations.

permeable barrier

A barrier that permits some aspects of an innovation to diffuse through it but weakens and retards continued spread; an innovation can be modified in passing through a permeable barrier.

Although all places and communities hypothetically have equal potential to adopt a new idea or practice, diffusion typically produces a core-periphery spatial arrangement. Hägerstrand offered an explanation of how diffusion produces such a regional configuration. The distribution of innovations can be random, but the overlap of new ideas and traits as they diffuse through space and time is greatest toward the center of the region and least at the peripheries. As a result of this overlap, more innovations are adopted in the center, or core, of the region.

16

Some other geographers, most notably James Blaut and Richard Ormrod, regard the Hägerstrandian concept of diffusion as too narrow and mechanical because it does not give enough emphasis to cultural and environmental variables and because it assumes that information automatically produces diffusion. They argue that nondiffusion—the failure of innovations to spread— is more prevalent than diffusion, a condition Hägerstrand’s system cannot accommodate. Similarly, the Hägerstrandian system assumes that innovations are equally beneficial to all people throughout geographical space. In reality, susceptibility to an innovation is far more crucial, especially in a world where communication is so rapid and pervasive that it renders the friction of distance almost meaningless. The inhabitants of two regions will not respond identically to an innovation, and the geographer must seek to understand this spatial variation in receptiveness to explain diffusion or the failure to diffuse. Within the context of their culture, people must perceive some advantage before they will adopt an innovation. As with most human-geographic models, diffusion helps us recognize persistent or recurring spatial patterns, but does not offer universally valid explanations.

MIGRATION

Increasingly, we see many other examples of mobility, such as the almost instant global communication about new ideas and technologies through computers and other digital media, the rapid movement of goods from the place of production to that of consumption, and the seemingly nonstop movement of money worldwide through digital financial networks. These types of movements through space do not necessarily follow the pattern of core-periphery but instead create new and different types of patterns. The term circulation might better fit many of these forms of mobility because this term implies an ongoing set of movements with no particular center or periphery.

circulation

An ongoing set of movements of people, ideas, or things that have no particular center or periphery.

Other types of mobilities, such as mass movements of people between different regions, can be best thought of as migrations from one region or country to another through particular routes. The spatial characteristics of human migrations have long been of interest to geographers, some of whom attempted to establish quantitative models. Hägerstrand, for example, used regression analysis to quantify the effects of distance decay on migration patterns. More recently, geographers have become interested in explaining the social and economic causes and consequences of migration. For example, geographers have analyzed how migrations are linked to changing conditions in labor markets, noting a general pattern of migration from areas of low employment or low wages to areas of higher employment or higher wages. Geographers are also increasingly interested in probing the subjective experience of migrants, both in places of origin and places of destination. Jeremy Foster, for example, studied the experiences of European migrants in colonial South Africa to reveal how painting, photography, poetry, and other forms of artistic expression are being used to transform a foreign land into a homeland. That is, Foster is interested in how migrants come to feel “at home” (or not) in a foreign land through engagement with certain kinds of cultural practices.

migrations

The large-scale movements of people between different regions of the world.

Migration implies the crossing of boundaries of some sort. Migration that crosses country borders is considered international migration. All residents of the United States, with the exception of Native Americans, can trace their presence in the country to international migration, often multiple migrations from different points of origin, via different routes, and at different times. One’s “American” ancestry might easily involve early-eighteenth-century migration from western Europe, nineteenth-century migration from North Africa, and twentieth-century migration from East Asia. This example illustrates some of the primary characteristics geographers use to categorize migration, including spatial scale (regional/global), time (temporary/permanent), and distance (long/short).

international migration

Human migration across country borders.

17

Migration that occurs within the borders of a country is classified as internal migration. A classic example of internal migration from the United States is the Great Migration. It refers to the twentieth-century movement of 6 million African Americans from the rural southern states to the cities of the midwestern and northeastern states. Such mass migrations have deep, long-lasting impacts on social, economic, and cultural conditions in both the places of origin and of destination. We can view the Great Migration as a significant, but relatively small, part of a global-scale pattern of mass migration from rural to urban areas sparked by the Industrial Revolution. In 2007 the United Nations determined that for the first time in human history, the majority of the world’s population lived in cities. This historic urbanization is primarily the result of rural to urban migration now experienced by nearly every country in the world.

internal migration

Human migration that occurs within the borders of a country.

Great Migration

The twentieth-century movement of 6 million African Americans from the rural southern states to the cities of the midwestern and northeastern states.

Whether international or internal, geographers have a system for categorizing types of migration. Stepwise migration is migration conducted in a series of stages. Migration might begin with a move from the countryside to a provincial capital. From there the migration continues to a country’s capital city and then might proceed across international borders to another country. Such stepwise migrations can take place over the course of one or more generations. Return migration refers to the phenomenon of migrants going back to their place of origin after long-term residency elsewhere. For example, it is not uncommon for migrants to return to their home countries upon reaching retirement age, even after spending most of their adult lives working abroad. Finally, seasonal migration refers to annual cycles of movement based on the time of year. Agricultural workers are often seasonal migrants because labor demand is seasonally variable and highly concentrated during the harvest periods of particular crops in particular places.

stepwise migration

Human migration conducted in a series of stages.

return migration

The phenomenon of migrants returning to their place of origin after long-term residency elsewhere.

seasonal migration

Usually associated with crop harvest periods, migrants move according seasonal changes in weather.

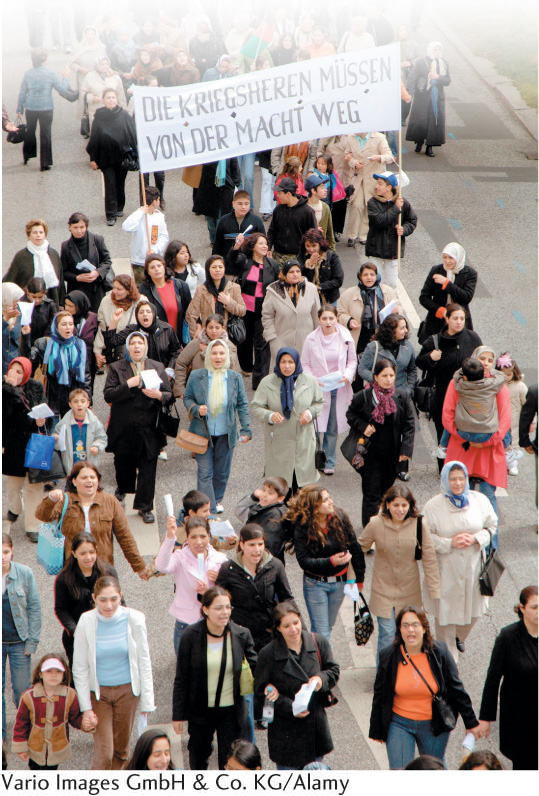

In today’s globalizing world, with better and faster communication and transportation technologies, many migrants more easily maintain ties to their homelands even after they have migrated, and some may move back and forth between their home countries and those to which they have migrated. Scholars refer to this kind of migration as transnational migration (Figure 1.10). We will discuss these different patterns of mobility in greater detail throughout the rest of the book.

transnational migration

The movement of groups of people who maintain ties to their homelands after they have migrated.

18

An Attack on Equality

![]() West Virginia, Still Home

West Virginia, Still Home

This video focuses on McDowell County, West Virginia, describing the recent decline of the region’s coal industry and resulting outmigration of most of its population. Despite the economic hardship and social upheaval, many remaining residents cannot imagine living elsewhere and remain deeply attached to the landscape. One resident tells the camera, “We are very connected to these mountains,” a sentiment that reveals a strong sense of place, belonging and regional identity. As we have learned in this chapter, the relationship between people and the places and landscapes in which they live is a main topic of study for human geographers. Quite a few other basic ideas in human geography are expressed by the video as well.

Thinking Geographically:

The video shows how social and economic forces operate across geographic scales— the global slump in the demand for coal and mechanization in the coal industry nationwide have led to the decline of once prosperous and well-populated towns in a southern corner of West Virginia. Can you think of similar examples in the area where you live or with which you are familiar?

One of the residents in the video spoke of a “brain drain” and another of her hopes that some of those people will “have the desire to come back to this community” How do these and other statements about the town’s population relate to the discussion of migration in this textbook? How many types of migration are illustrated in the video?

Recall the various ways that the concept of region was discussed in the chapter. How many of those concepts are illustrated by the case of McDowell County?

How does this video illustrate the concepts of place and topophilia? Think about the personal histories of some of the residents interviewed and their onscreen statements about the town and surrounding landscape. What sorts of emotions and sentiments do people express when discussing their home?