NATURE-CULTURE

1.4

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Define the different models of nature-culture relations.

The themes of region, mobility, and globalization help us understand patterns, movements, and interconnections that characterize the ways in which people create spatial patterns on the Earth. Our fourth theme, nature-culture, adds a different dimension to this analysis; it focuses our attention literally on how people inhabit the Earth, their relationships to the physical environment. This theme helps us investigate how groups of people interact with the Earth’s biophysical environment and examine how the culture, politics, and economies of those groups affect their ecological situation and resource use. Human geographers view the relationship between people and nature as a two-way interaction. People’s cultural values, beliefs, perceptions, and practices have ecological impacts, and ecological conditions, in turn, influence cultural perceptions and practices. The human geographer must study the interaction between culture and environment to understand spatial variations in culture.

nature-culture

Refers to the complex relationships between people and the physical environment, including how culture, politics, and economies affect people’s ecological situation and resource use.

The term ecology was coined in the nineteenth century to refer to a new biological science concerned with studying the complex relationships among living organisms and their physical environments. Geographers borrowed this term in the mid-twentieth century and joined it with the term culture to identify a field of study—cultural ecology—that dealt with the interaction between culture and physical environments. Later, another concept, the ecosystem, was introduced to describe a territorially bounded system consisting of interacting organic and inorganic components. Plant and animal species were said to be adapted to specific conditions in the ecosystem and to function so as to keep the system stable over time.

cultural ecology

Broadly defined, the study of the relationships between the physical environment and culture; narrowly (and more commonly) defined, the study of culture as an adaptive system that facilitates human adaptation to nature and environmental change.

It soon became clear, however, that human cultural interactions with the environment were far too complex to be analyzed with concepts borrowed from biology. Furthermore, the idea that groups of people interacted with their ecosystems in isolation from larger-scale political, economic, and social forces was difficult to defend. We can readily observe, for example, that trade goods come into communities, agricultural commodities flow out, money circulates, taxes are collected, and people migrate in and out for work. So, geographers now use the term nature-culture to refer to the complex interactions among all these variables and to reflect the fact that studies of local human-environment relations need to include political, economic, and social forces operating on national, and even global, scales.

The theme of nature-culture, the meeting ground of cultural and physical geographers, has traditionally provided a focal point for the academic discipline of geography. In fact, some geographers have proposed that the theme of geography is nature-culture: that the study of the intricate relationships between people and their physical environments unites cultural and physical geography to form the entire academic discipline. Although few accept this narrow definition of geography, most will agree that an appreciation of the complex people-environment relationship is necessary for concerned citizens of the twenty-first century.

Through the years, human geographers have developed various perspectives on the interaction between humans and the land. Four schools of thought have developed: environmental determinism, possibilism, environmental perception, and humans as modifiers of the Earth.

22

Mona’s Notebook: Early-Twentieth-Century Globalization Versus Contemporary Globalization in Russia

Mona’s Notebook

Early-Twentieth-Century Globalization Versus Contemporary Globalization in Russia

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I took the photo below during my second research trip to Moscow in 2006, when I hoped to spend my time in archives hunting down information about how and in what ways U.S.-based corporations had expanded into Russia in the early twentieth century. Russia was America’s largest foreign market at the time, so I knew it held one of the keys to figuring out my primary research question: how and why early globalization was different from and similar to contemporary globalization. The archives were indeed filled with information (though extremely difficult to access), but I soon understood that I could learn almost as much from walking the streets as I could from sitting, squinting, and typing in closed-off archival rooms. What I saw was a city in the midst of a huge consumer revolution, funded with money from Russian natural gas and oil, and capitalized by global corporations. Construction cranes were everywhere because large, globally based development companies saw profitable opportunities in the skyrocketing demand for housing, entertainment, and shopping spaces.

One hundred years earlier, as I found out in the archives, Moscow was in a similar situation, though the scale and pace of globalization was much smaller and slower. In addition to German, French, and British companies, U.S.-based companies sought out Russia as a market because of its large population and relatively underdeveloped industrial sector. Parts of downtown Moscow in 1915 began to resemble Wall Street and Broadway: a landscape filled with corporate headquarters, bank and insurance buildings, department stores, and even a stock exchange. Of course, as we all know from our history classes, all of this came to an abrupt halt in 1917, when those not benefiting from globalization (or the czar’s government!) changed the entire system. Today the outcome seems markedly different. If what I learned from walking the streets of Moscow today is indicative, twenty-first-century globalization is there to stay.

23

ENVIRONMENTAL DETERMINISM

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many geographers accepted environmental determinism: the belief that the physical environment is the dominant force shaping cultures and that humankind is essentially a passive product of its physical surroundings. Humans are clay to be molded by nature. Similar physical environments produce similar cultures.

environmental determinism

The belief that cultures are directly or indirectly shaped by the physical environment.

For example, environmental determinists believed that peoples of the mountains were predestined by the rugged terrain to be simple, backward, conservative, unimaginative, and freedom loving. Desert dwellers were likely to believe in one God but to live under the rule of tyrants. Temperate climates produced inventiveness, industriousness, and democracy. Coastlands pitted with fjords produced great navigators and fishers. Environmental determinism had serious consequences, particularly during the time of European colonization in the late nineteenth century. For example, many Europeans saw Latin American native inhabitants as lazy, childlike, and prone to vices such as alcoholism because of the tropical climates in much of this region. Living in a tropical climate supposedly ensured that people didn’t have to work very hard for their food. Europeans were able to rationalize their colonization of large portions of the world in part along climatic lines. Because the natives were “naturally” lazy and slow, the European reasoning went, they would benefit from the presence of the “naturally” stronger, smarter, and more industrious Europeans who came from more temperate lands.

24

Determinists overemphasize the role of environment in human affairs. This does not mean that environmental influences are inconsequential or that geographers should not study such influences. Rather, the physical environment is only one of many forces affecting human culture and is never the sole determinant of behavior and beliefs.

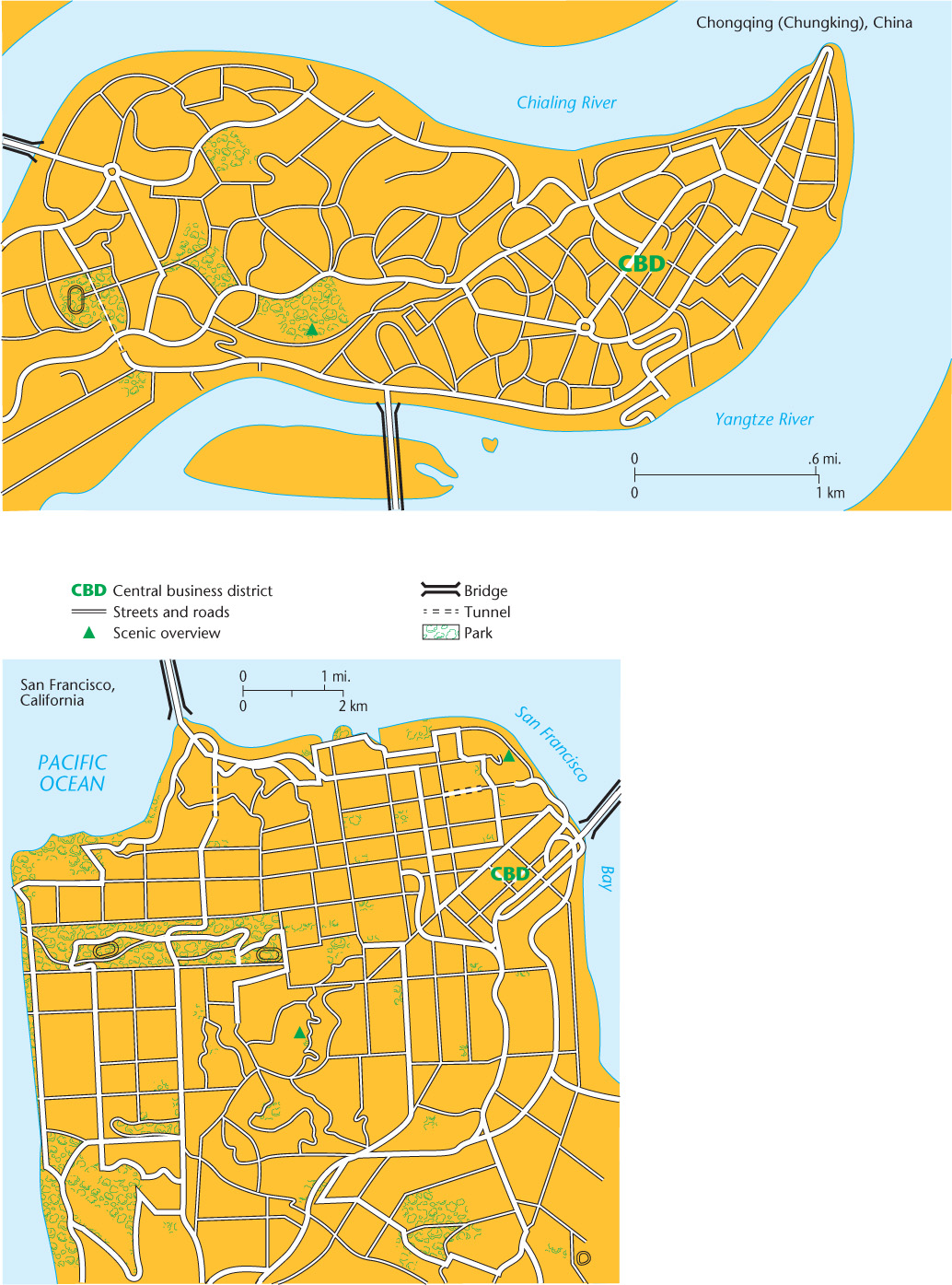

POSSIBILISM

After the 1920s, possibilism became a prominent view among geographers. Possibilists claim that any physical environment offers a number of possible ways for a culture to develop. In this way, the local environment helps shape its resident culture. However, a culture’s way of life ultimately depends on the choices people make among the possibilities offered by the environment. These choices are guided by cultural heritage and are shaped by a particular political and economic system. Possibilists see the physical environment as offering opportunities and limitations; people make choices among these to satisfy their needs. Figure 1.12 provides an interesting example: the cities of San Francisco and Chongqing both were built on similar physical terrains that dictated an overall form, but differing cultures lead to very different street patterns, architecture, and land use. In short, local traits of culture and economy are the products of culturally based decisions made within the limits of possibilities offered by the environment.

possibilism

A school of thought based on the belief that humans, rather than the physical environment, are the primary active force; that any environment offers a number of different possible ways for a culture to develop; and that the choices among these possibilities are guided by cultural heritage.

Most possibilists believe that the higher the technological level of a culture, the greater the number of possibilities and the weaker the influences of the physical environment. Technologically advanced cultures, in this view, have achieved some mastery over their physical surroundings. Geographers Jim Norwine and Thomas Anderson, however, warn that even in these advanced societies “the quantity and quality of human life are still strongly influenced by the natural environment,” especially climate. They argue that humankind’s control of nature is anything but supreme and perhaps even illusory. One only has to think of the devastation caused by the January 2010 earthquake in Haiti or the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan to underscore the often-illusory character of the control humans think they have over their physical surroundings.

ENVIRONMENTAL PERCEPTION

Another approach to the theme of nature-culture focuses on how humans perceive nature. Each person and cultural group has mental images of the physical environment, shaped by knowledge, ignorance, experience, values, and emotions. To describe such mental images, human geographers use the term environmental perception. Whereas the possibilist sees humankind as having a choice of different possibilities in a given physical setting, the environmental perceptionist declares that the choices people make will depend more on what they perceive the environment to be than on the actual character of the land. Perception, in turn, is colored by the teachings of culture.

environmental perception

The belief that culture depends more on what people perceive the environment to be than on the actual character of the environment; perception, in turn, is colored by the teachings of culture.

Some of the most productive research done by geographers who are environmental perceptionists has been on the topic of natural hazards, such as floods, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, insect infestations, and droughts. Natural hazards are sometimes called “acts of God,” to highlight that such disasters are beyond human control. A closer look, however, reveals that there is usually some human input into the making of disasters. Hazards are often well known, but economic interests, poverty, or political problems inhibit proper planning. For example, towns in the upper Mississippi River drainage basin were built close to the riverbanks to facilitate commerce, but were then vulnerable to the flooding common in the region. Sometimes hazards are known, but collectively forgotten because the time between disastrous occurrences is great and people become complacent. And sometimes human-made hazards combine with natural hazards to create even worse disasters. Human-made hazards include such things as pollution and contamination from industrial production. Thus, it is often difficult and even misguided to attempt to separate the natural from the human in understanding vulnerability to hazards.

natural hazard

An inherent danger present in a given habitat, such as floods, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, or earthquakes; often perceived differently by different peoples.

25

26

Japan’s so-called triple disaster illustrates the extent and complexity of nature-culture coupling inherent in natural hazards (Figure 1.13). On the afternoon of March 11, 2011, a strong earthquake occurred in the northwestern Pacific Ocean near Japan’s coast. The resulting shock waves were felt in major cities across Japan, but government planning minimized the impacts. Because the country is prone to earthquakes, the government has invested in new construction technologies, enforced some of the world’s strictest building codes, and installed an early earthquake warning system. These initiatives prevented property damage and saved many lives in Tokyo and other cities.

The earthquake, however, produced an 8-meter displacement in the seafloor, resulting in a tsunami (a wave produced by the displacement of a large volume of water). Within an hour of the initial earthquake, the tsunami began flooding coastal areas at heights ranging from 3 to 7 meters. Though the government also had installed a tsunami warning system, it was inadequate to deal with the magnitude of the flooding. Indeed, dozens of government evacuation shelters, which were supposedly out of harm’s way, were flooded and destroyed. It was later revealed that previous generations of residents had marked the coastline with stone tablets warning of the tsunami hazard. Some markers were hundreds of years old and advised residents to not build below certain elevations. The Japanese government and most present-day residents did not heed these warnings, with the result that whole towns and ports were swept away by the 2011 tsunami.

The third disaster followed the tsunami, which destroyed the electrical power infrastructure and inundated nuclear power facilities along the coast. At the Fukushima Daiichi and Daini power plants, the waves swept over seawalls and destroyed the backup power systems. As a result, the plants were without electrical power and unable to maintain control of radioactive materials on site. Several explosions and radioactivity leakage followed, leading to the evacuation of over 200,000 people. As the nuclear reactors melted down, it became clear that the company in charge had failed to adequately plan for the tsunami hazard. The releases of radioactivity left many areas uninhabitable, caused the closure of local fisheries, and spurred the government to abandon nuclear power as an energy source for the nation. Japan’s triple disaster demonstrates how labeling a hazard “natural” or an “act of God” masks the human component present in all disasters.

27

In virtually all cultures, people knowingly inhabit hazard zones, especially floodplains, exposed coastal sites, drought-prone regions, and the environs of active volcanoes. In the United States, for example, every year more people live in areas subject to frequent hurricanes along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico and atop earthquake faults in California. How accurately do they perceive the hazard involved? Why have they chosen to live in such places? How might we minimize the eventual disasters? Human geographers seek the answer to these questions and aspires, with other experts, to mitigate the inevitable disasters through such strategies as land-use planning.

Perhaps the most fundamental expression of environmental perception lies in the way different cultures see nature itself. We must understand at the outset that nature is a culturally derived concept that has different meanings to different peoples. In the organic view of nature, people are part of nature. In many cultures around the globe, elements of the natural environment—trees, animals, landscape features, and so forth—are believed to be animated by various types of spirits. Thus, human lives are seen as intimately intertwined with natural phenomena. Many indigenous peoples around the world hold this view, but increasingly many environmental activists in Westernized cultures have adopted similar positions. By contrast, the dominant Western philosophical tradition offers a mechanistic view of nature. Humans are separate from and hold dominion over nature. This philosophy sees nature as an integrated system of mechanisms governed by external forces that can be rendered into natural laws and understood and controlled by people.

organic view of nature

The view that humans are part of, not separate from, nature and that elements of the natural environment are animated by various types of spirits.

mechanistic view of nature

The view that humans are separate from nature and hold dominion over it, and that nature is an integrated system of mechanisms governed by external forces which humans can render into natural laws and control.

HUMANS AS MODIFIERS OF THE EARTH

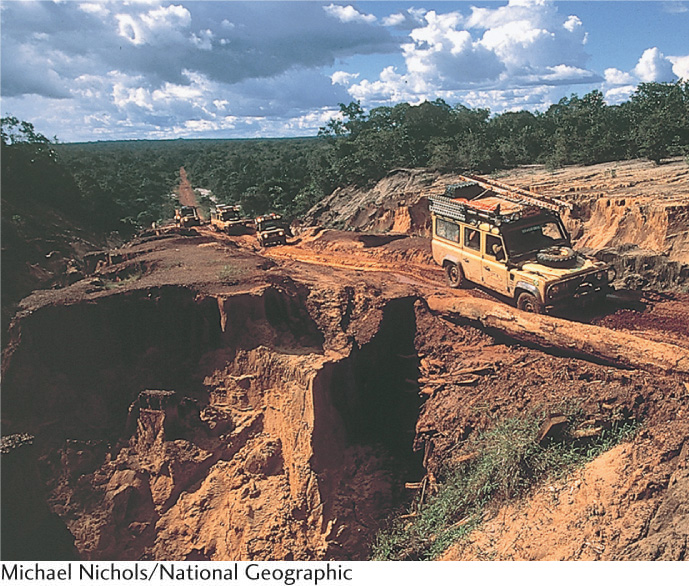

Many human geographers, observing the environmental changes people have wrought, emphasize humans as modifiers of the habitat. This presents yet another facet of the theme of nature-culture. In a sense, the human-as-modifier school of thought is the opposite of environmental determinism. Whereas the determinists proclaim that nature molds humankind, and possibilists believe that nature presents possibilities for people, those geographers who emphasize the human impact on the land assert that humans mold nature.

In addition to deliberate modifications of the Earth through such activities as mining, logging, and irrigation, we now know that even seemingly innocuous behavior, repeated for millennia, for centuries, or in some cases for mere decades, can have catastrophic effects on the environment. Plowing fields and grazing livestock can eventually denude regions (Figure 1.14). The use of certain types of air conditioners or spray cans apparently has the potential to destroy the planet’s very ability to support life. And the increasing release of fossil-fuel emissions from vehicles and factories—what are known as greenhouse gases—is leading to global warming, with potentially devastating effects on the Earth’s environment (see Subject to Debate in the next section). Clearly, access to energy and technology is the key variable that controls the magnitude and speed of environmental alteration. Geographers seek to understand and explain the processes of environmental alteration as they vary from one culture to another and, through applied geography, to propose alternative, less destructive modes of behavior.

28

Gender differences can also play a role in the human modification of the Earth. Ecofeminism, a term derived from a book by Karen Warren, maintains that because of socialization, women have been better ecologists and environmentalists than men. Traditionally, women—as childbearers, gardeners, and nurturers of the family and home—dealt with the daily chores of gathering food from the Earth, whereas men—as hunters, fishers, warriors, and forest clearers—were involved with activities more associated with destruction. Regardless of whether we agree with this rather deterministic and essentializing viewpoint (i.e., understanding gender differences as biologically determined rather than culturally constructed), we can see that in many situations through time, and around the globe, women and men have had different relationships to the natural world.

ecofeminism

A doctrine proposing that women are inherently better environmental preservationists than men because of their traditional roles of creating and nurturing life, whereas the traditional roles of men too often necessitated death and destruction.