CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

2.5

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Recognize how landscapes reflect cultural differences.

The theme of cultural landscape reveals the important differences within and between cultures.

FOLK ARCHITECTURE IN NORTH AMERICA

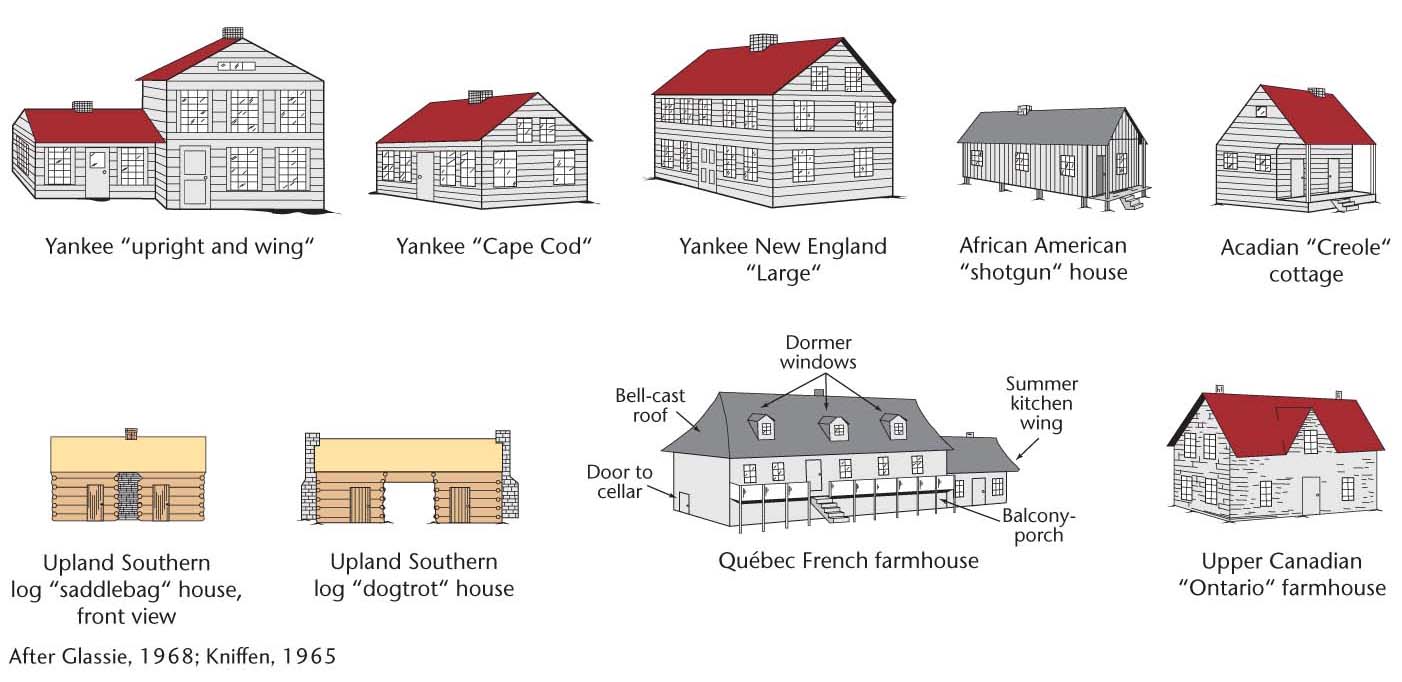

Every folk culture produces a highly distinctive landscape. One of the most visible aspects of these landscapes is folk architecture. These traditional buildings illustrate the theme of folk cultural landscape. Folk architecture springs not from the drafting tables of professional architects but from the collective memory of groups of a people (Figure 2.46). Material composition, floor plan, and layout are important ingredients of folk architecture, but numerous other characteristics help classify farmsteads and dwellings. The form or shape of the roof, the placement of the chimney, and a building’s location and orientation in the physical environment are important classifying criteria as well.

folk architecture

Structures built by members of a folk society or culture in a traditional manner and style, without the assistance of professional architects or blueprints, using locally available raw materials.

77

Rod's Notebook: Encountering Nature

Rod’s Notebook

Encountering Nature

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In popular culture, fewer and fewer of us have direct contact with what we might call wild nature. We don’t make our livings by hunting, clearing fields, or pasturing livestock in the mountains. Rather, mass media, particularly television and film documentaries, shape our understanding of nature and wild places. Wild nature has been transformed into a spectacle in popular culture, something for our amusement and entertainment.

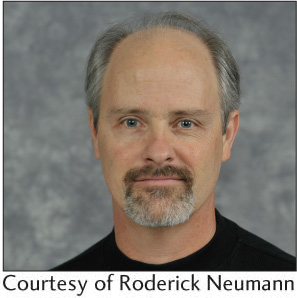

I was conducting research in the historical records of Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park when these observations were driven home to me in a very powerful way. Serengeti, like the Amazon, is one of those iconic wild places in popular culture. Who hasn’t seen a Serengeti cheetah blazing across the television screen in pursuit of a panicked wildebeest?

I spent my days looking through archived files at the park’s research headquarters and my evenings at the Seronera Wildlife Lodge, a luxury hotel in the heart of the African “wilds.” I would watch vanloads of American and European (but no African) tourists return to the lodge from their daily wildlife safaris. We would all perch on the balcony with beers or cocktails, watching the elephants, gazelles, and baboons gather at the artificial watering hole just meters away. Drawn to water in the arid landscape, these beasts daily provided us with an entertaining spectacle of wild African nature without our having to leave the bar!

After dark, people would move inside and gather around a television in the lounge and watch—wait for it!—television documentaries about wildlife in Serengeti. I was witnessing an almost surreal feedback loop in which urbanized tourists, drawn to East Africa by the television documentaries they’d viewed in their living rooms in the United States, now sat in front of a television set in the middle of Serengeti watching the wildlife they’d seen that day or hoped to see tomorrow. It seemed as if the television in the lounge was needed to reinforce the reality of the actual experience of viewing African wildlife firsthand. Such is the power of mass media in shaping human encounters with wild nature in popular culture.

78

In the United States and Canada, folk architecture today is a relic. Traces can still be found here and there and provide both a sense of past cultural landscapes and enduring symbols of cultural identity. One needs to know what to be on the lookout for in folk houses, however, in order to properly "read" the landscape. Yankee folk houses, for example, are of wooden frame construction, and shingle siding often covers the exterior walls. They are built with a variety of floor plans, including the New England "large" house, a huge two-and-a-half-story house built around a central chimney and two rooms deep. As the Yankee folk migrated westward, they developed he upright-and-wing dwelling. These particular Yankee houses are frequently massive, in part because the cold winters of the region forced most work to be done indoors.

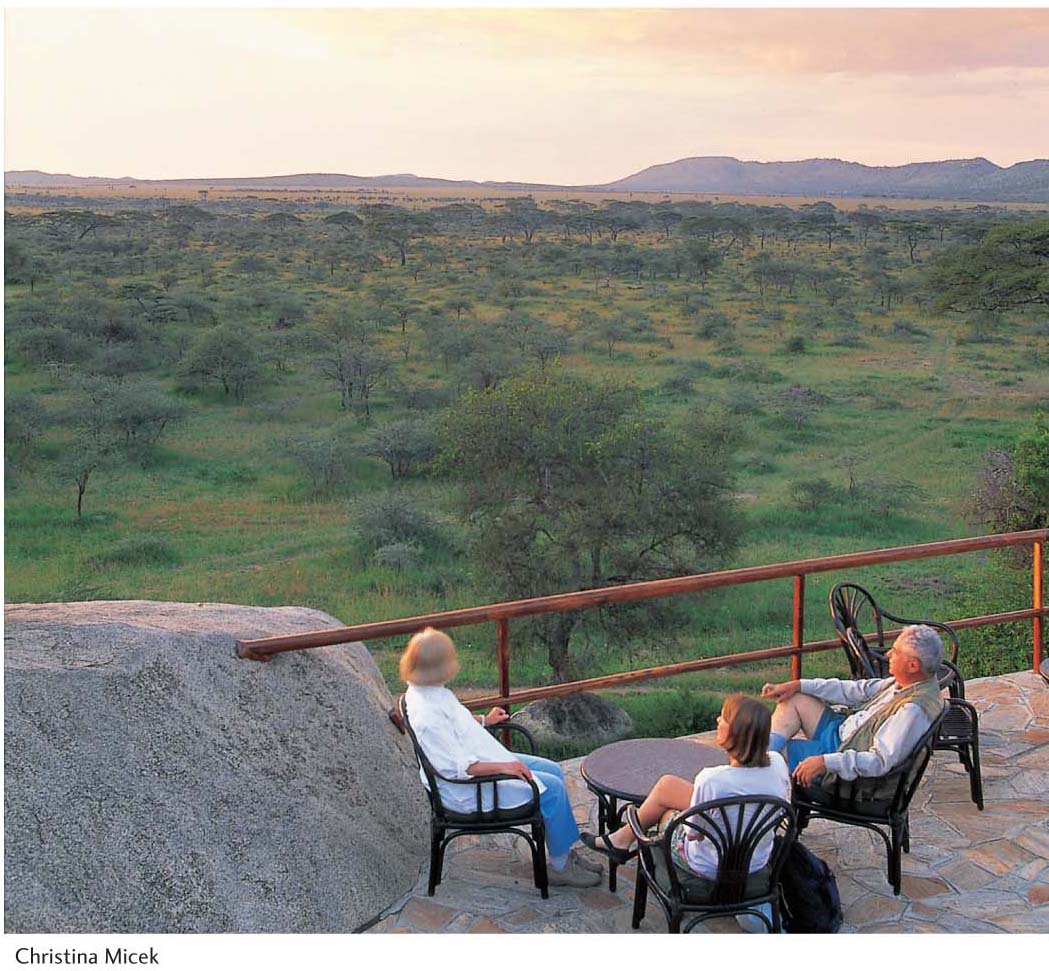

By contrast, Upland Southern folk houses are smaller and built of notched logs. Many houses in this folk tradition consist of two log rooms, with either a double fireplace between, forming the saddlebag house, or an open, roofed breezeway separating the two rooms, a plan known as the dogtrot house (Figure 2.47). An example of an African American folk dwelling is the shotgun house, a narrow structure only one room in width but two, three, or even four rooms in depth. Acadiana, a French-derived folk region in Louisiana, is characterized by the half-timbered Creole cottage, which has a central chimney and built-in porch. Scores of other folk house types survive in the American landscape, although most such dwellings are now abandoned.

Canada also offers a variety of traditional folk houses (see Figure 2.46). In French-speaking Québec, one of the common types consists of a main story atop a cellar, with attic rooms beneath a curved, bell-shaped (or bell-cast) roof. A balcony-porch with railing extends across the front, sheltered by the overhanging eaves. Attached to one side of this type of French-Canadian folk house is a summer kitchen that is sealed off during the long, cold winter. Often the folk houses of Québec are built of stone. To the west, in the Upper Canadian folk region, one type of folk house occurs so frequently that it is known as the Ontario farmhouse. One-and-a-half stories in height, the Ontario farmhouse is usually built of brick and has a distinctive gabled front dormer window. Now that we have reviewed a few of the common styles of North American folk architecture, you can test your ability to identify them in the landscape (Figure 2.48).

79

FOLK ARC HITECTURE AROUND THE WORLD

Although in North America folk architecture tends to be found only as a cultural relic of the past, it continues to thrive in regions where agriculture is the main occupation. Most construction is done with local materials such as clay, stone, wood, bamboo, leaves, and grasses. Distinctive cultural landscapes emerge from the collective use of folk architecture, just two examples of which we present here.

80

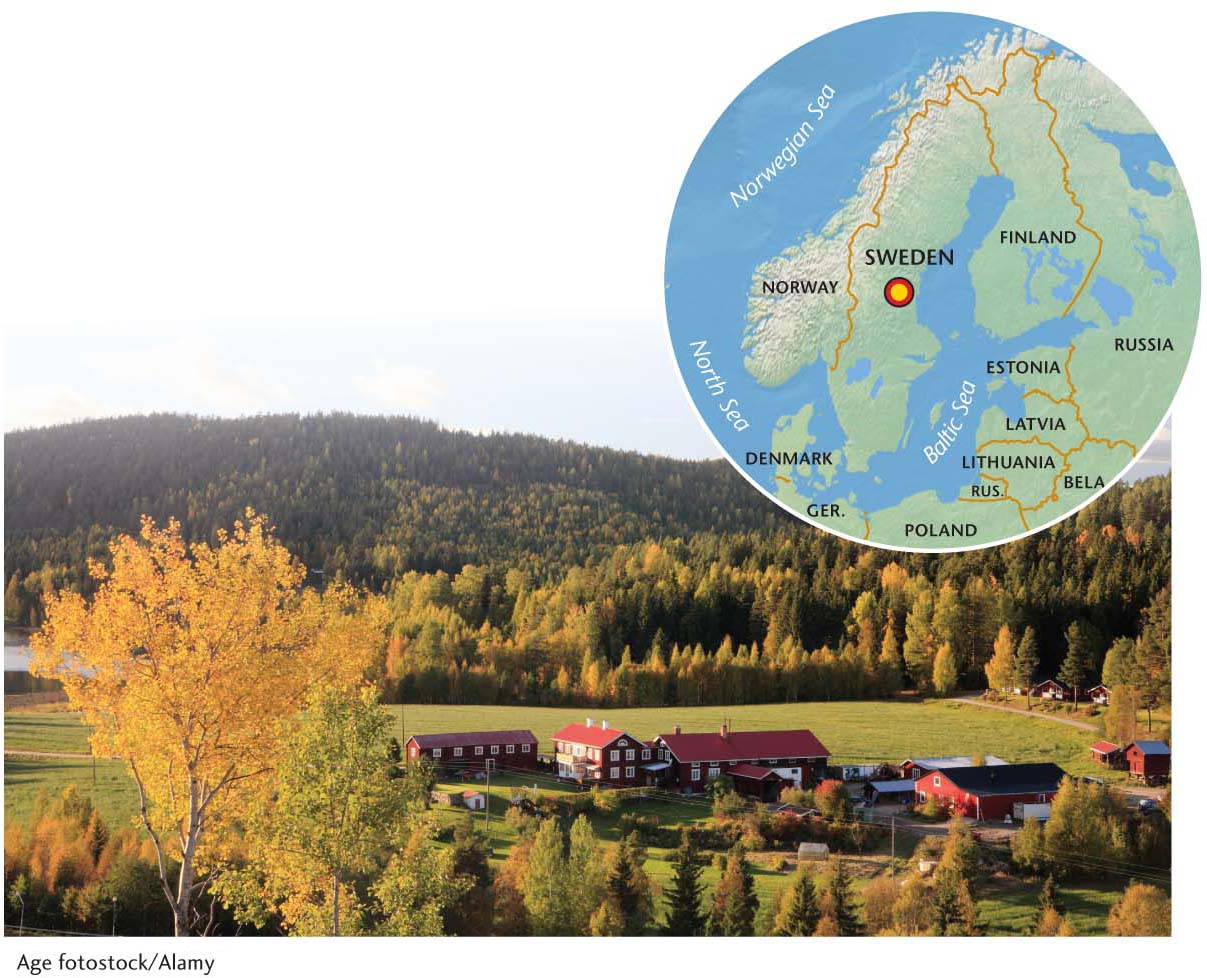

World Heritage Site: Decorated Farmhouses of Hälsingland

World Heritage Site

Decorated Farmhouses of Hälsingland

Folk architecture has given way to professionally built and mass-produced housing. Recognizing that important cultural heritage is vanishing, in 2012 UNESCO designated seven large farmhouses in northeastern Sweden’s Hälsingland region as the Decorated Farmhouses of Hälsingland World Heritage Site. Out of more than 1000 possibilities, the committee chose these seven as outstanding examples of a regional folk architecture rooted in the Middle Ages. The timber farmhouses were constructed mostly between 1800 and 1870 C.E. and are richly decorated, inside and out, following a local folk art tradition

◼ Hälsingland, a small region in Sweden bordering the Gulf of Bothnia, contains a concentration of such farmhouses. The seven UNESCO-designated farmhouses are spread over an area stretching 100 by 50 kilometers. Both they and the surrounding landscapes are protected under Swedish cultural heritage and environmental laws, reflecting their importance to that nation’s cultural identity.

◼ The Decorated Farmhouses of Hälsingland represent the final flourishing of a centuries-old local tradition of timber construction. Beginning in the early nineteenth century, farmers in the region experienced a new period of prosperity based on forestry and flax production. Farmers invested their surplus earnings into building and decorating farmhouses. Most of these structures remain under the private ownership of farmers who continue to manage the surrounding lands for agriculture.

◼ The cultural landscape of Hälsingland has evolved over centuries and bears the imprint of occupation by a population of independent farmers. The decorated farmhouses are located on active farmsteads and within a larger agrarian landscape. The mixed agrarian livelihood practices of cattle breeding, crop cultivation, forestry, and hunting have visibly shaped the land. Historically, farmers used the pastures and woodlands communally and shared cultivated fields. Changes in Swedish law in the nineteenth century led to individual privatization of lands, which brought prosperity to some farmers and a flowering of folk architecture.

81

IN THE FARMHOUSES: The seven designated farmhouses are the Kristofers farm in Stene, Järvsö; the Gästgivars farm in Vallstabyn; the Pallars farm in Långhed; the Jon-Lars farm in Långhed; the Bortom åa farm in Gammelgården; the Bommars farm in Letsbo, Ljusdal; and the Erik-Anders farm in Askesta, Söderala. Each contains a number of decorated rooms for festivities and some very prosperous farmsteads have entire houses, a herrstuga, dedicated solely to festive celebrations. The farmsteads feature numerous intact buildings that were built and elaborately painted in a manner meant to display the prosperity and social status of the farmer.

◼ The houses are made entirely of wood, most constructed in a building tradition that may be traced to the Middle Ages, which features jointed horizontal timbers of pine or spruce from nearby forests. Prosperous farmers of the nineteenth century enlarged existing houses from one to two or two and a half stories or built entirely new houses on the farmstead. The emphasis was on creating exceptionally large structures using the most talented local carpenters and craftsmen.

◼ Each farmhouse is elaborately decorated. On the outside, local craftsmen carved decorative elements around the front porch and main entrance. Inside, the houses are decorated with textile paintings hung on the walls or with paintings applied directly to the wooden walls and ceilings. The rooms dedicated solely for festivities and special occasions are typically the most highly decorated.

◼ The paintings fuse local folk art traditions with more universal styles, such as Baroque and Rococo, favored by the landed gentry of nineteenth-century Sweden. Wealthy farmers commissioned itinerant artists to paint their farmhouse interiors with depictions of landscapes and biblical characters in contemporary fashion or with detailed floral patterns. Ten of the painters who worked on the World Heritage farmhouses are known, but most remain anonymous.

TOURISM: The seven UNESCO-designated farmhouses are located in a scenic coastal region of northeastern Sweden, which has long been an attraction for both domestic and foreign tourists.

◼ Regional public and business groups, as well as individual farmers, actively collaborate to keep decorated farmhouses open to visitors. Museums in the region feature displays on the history of this folk tradition.

◼ The maintenance and conservation of Swedish cultural heritage is a popular movement in the country. Many craftsmen and women in Hälsingland carry on folk handicrafts, such as textiles, furniture making, and basketry, which draw many visitors to the region.

◼ Established between 1800 and 1870 C.E., these farmsteads in northeastern Sweden represent the final flowering of a centuries-old tradition of folk architecture.

◼ In 2012 seven farmhouses were designated as World Heritage Sites, being noteworthy examples of the elaborately decorated interiors characteristic of the Hälsingland’s region’s folk culture.

◼ Visitors are attracted to the region by its scenic beauty, agrarian landscapes, and celebration of local folk traditions and handicrafts.

82

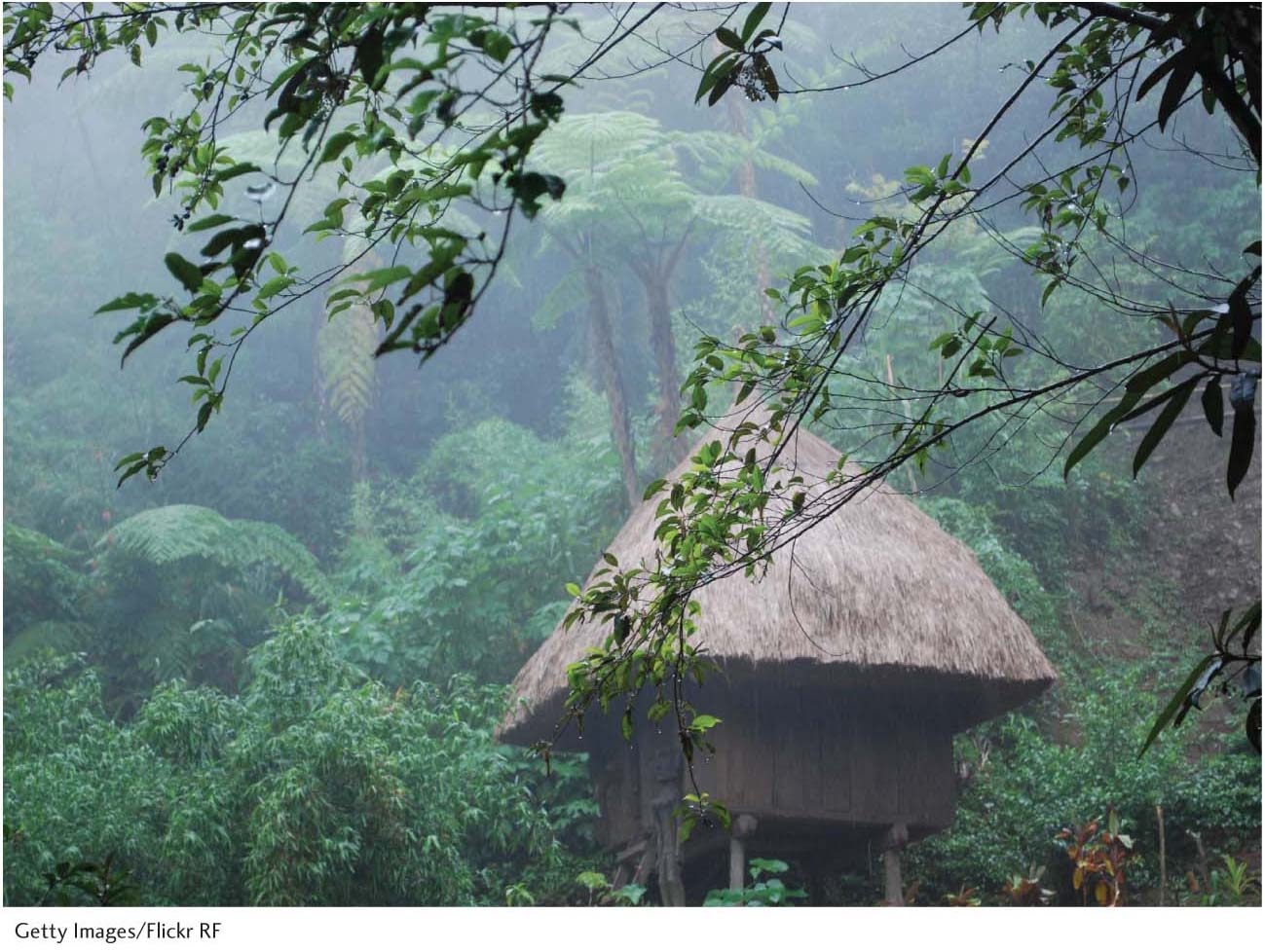

The characteristic folk housing of the Philippines is the nipa hut, still found in the countryside with many variations resulting from the mix of Malaysian, Spanish, Muslim, and American influences. Most commonly, it is constructed primarily of bamboo framing fastened and roofed with nipa leaves (Figure 2.49). Philippine folk architecture conveys a feeling of lightness (through, for example, the placement of large open-air windows) combined with a quality of warmth produced from the use of wood inside. The nipa hut is often raised on stilts, particularly in coastal areas and flood plains. The combination of large windows, wide roof eaves, and its elevated position results in the free flow of cooling breezes even during rainy weather. The nipa hut is widely considered as the Philippine national dwelling and thus is closely associated with cultural and national identity.

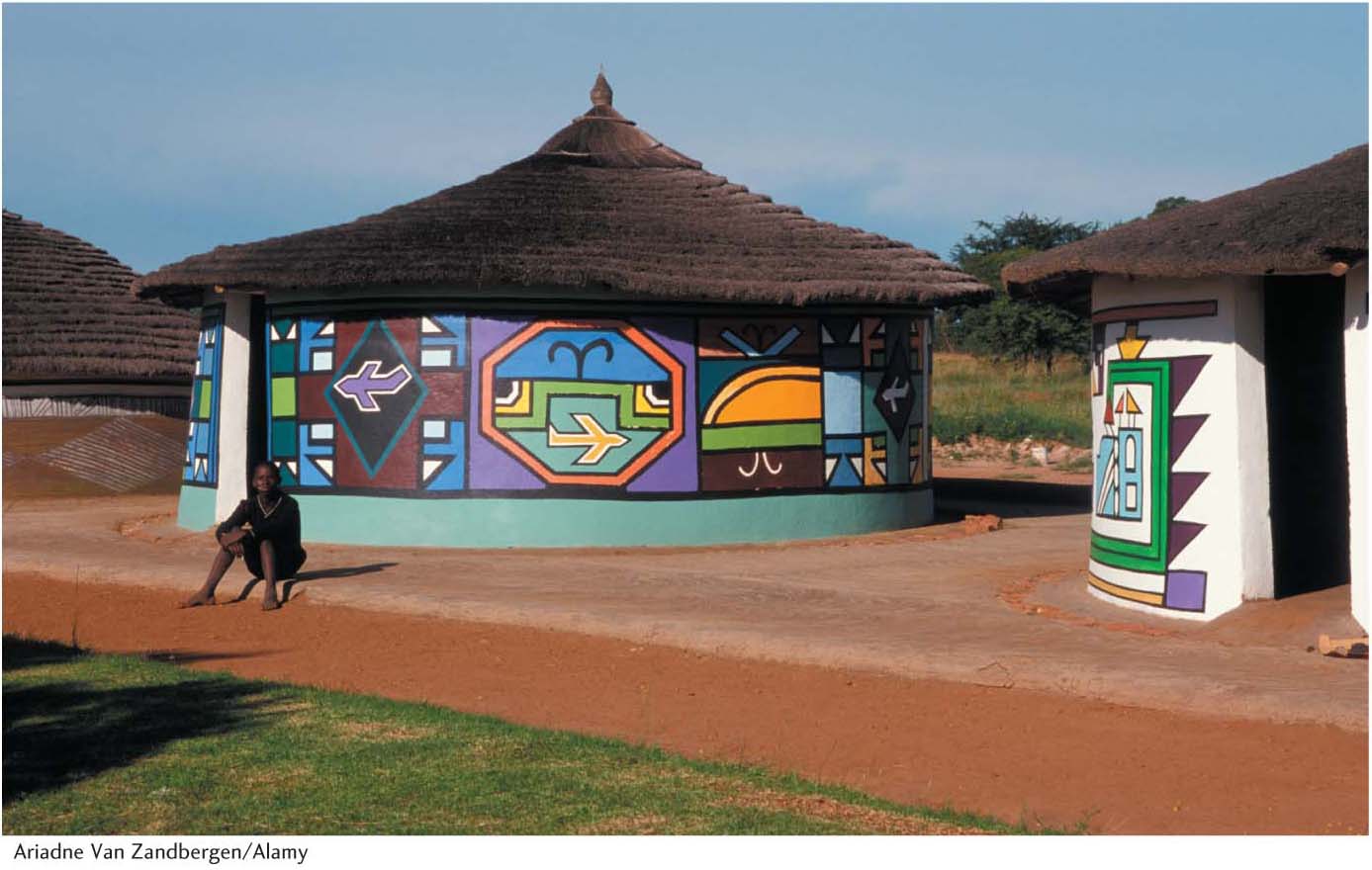

In southern Africa, one of the most distinctive house types is found in the Ndebele culture region, which stretches from South Africa north into southern Zimbabwe. In the rural parts of the Ndebele region, people are farmers and livestock keepers and live in traditional compounds. What makes these houses distinctive is the Ndebele custom of painting brightly colored designs on the exterior house walls and sometimes on the walls and gates surrounding the grounds (Figure 2.50). The precise origins of this custom are unclear, but it seems to date to the mid-nineteenth century. Some suggest that it was an assertion of cultural identity in response to local residents’ displacement and domination at the hands of white settlers. Others point to a religious or sacred role.

What is clear is that the custom has always been handled by women, a skill and practice passed down from mother to daughter. Many of the symbols and patterns are associated with particular families or clans. Initially, women used natural pigments from clay, charcoal, and local plants, which restricted their palette to earth tones of brown, red, and black. Today, many women use commercial paints-expensive, but longer lasting-to apply a range of bright colors, limited only by the imagination. Another new development is the types of designs and symbols used. People are incorporating modern machines such as automobiles, televisions, and airplanes into their designs. In many cases, traditional paints and symbols are blended with the modern to produce a synthetic design of old and new. Ndebele house painting is developing and evolving in new directions, all the while continuing to signal a persistent cultural identity to all who pass through the region.

LANDSCAPES OF CONSUMPTION

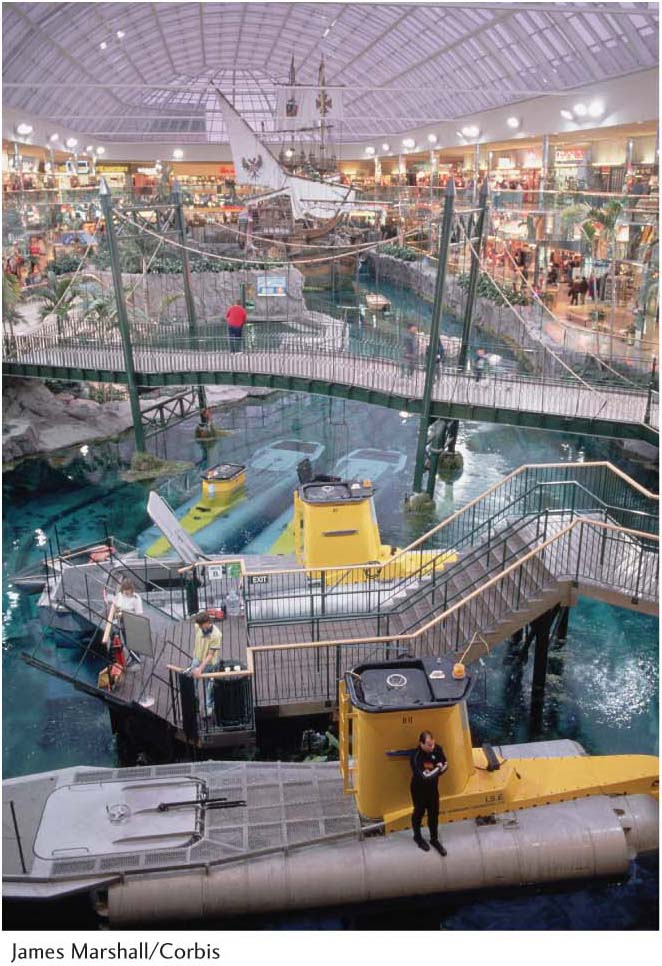

It is difficult to single out one type of popular landscape, just as it is difficult to distinguish one type of folk landscape. Popular culture has been, nonetheless, commonly associated with mass-produced suburban housing, commercial strips, and large indoor shopping malls. These latter retail districts have come to be known by geographer Robert Sack’s term, “landscapes of consumption” (refer back to Figure 2.8). Not only are such landscape features common in North America, they are now also seen in Brazil, China, India, and many other countries with rapidly growing economies increasingly linked through globalization (Figure 2.51). Indeed, the world’s ten largest (in terms of leasable area) indoor shopping malls may all be found outside of North America.

83

Of these, North America’s largest indoor mall is West Edmonton Mall in the Canadian province of Alberta (Figure 2.52). Enclosing some 5.3 million square feet (493,000 square meters) and opened in 1986, West Edmonton Mall employs 23,500 people in more than 800 stores and services, accounts for nearly one-fourth of the total retail space in greater Edmonton, earned 42 percent of the dollars spent in local shopping centers, and experienced 2800 crimes in its first nine months of operation. Beyond its sheer size, West Edmonton Mall also boasts a water park, a sea aquarium, an ice-skating rink, a miniature golf course, a roller coaster, 21 movie theaters, and a 360-room hotel. Its “streets” feature motifs from such distant places as New Orleans, represented by a Bourbon Street complete with fiberglass ladies of the evening. Jeffrey Hopkins, a geographer who studied this mall, refers to this as a “landscape of myth and elsewhereness,” a “simulated landscape” that reveals the “growing intrusion of spectacle, fantasy, and escapism into the urban landscape.”

LEISURE LANDSCAPES

Another common feature of popular culture is what geographer Karl Raitz labeled leisure landscapes. Leisure landscapes are designed to entertain people on weekends and vacations; often they are included as part of a larger tourist experience. Golf courses and theme parks such as Disney World are good examples of such landscapes. Amenity landscapes are a related landscape form. These are regions with attractive natural features such as forests, scenic mountains, or lakes and rivers that have become desirable locations for retirement or vacation homes. In much of Europe, rural regions that can no longer economically support agricultural production are increasingly viewed as leisure landscapes. Geographer Arjen Buijs and colleagues have documented in France and the Netherlands a shift in public understanding of rural landscape from one of a requirement for livelihood to one of an amenity offering comfort and convenience. Such shifts have strong implications for the future of rural life in western Europe, not least of which is the growing use of the countryside for vacation and retirement homes (Figure 2.53).

leisure landscapes

Landscapes planned and designed primarily for entertainment purposes, such as ski and beach resorts.

amenity landscapes

Landscapes prized for their natural and cultural aesthetic qualities by the tourism and real estate industries and their customers.

84

The past, reflected in surviving buildings, has also been incorporated into leisure landscapes. Most often, folk or historic buildings that cannot be preserved in place are relocated to create a sort of outdoor museum. Many small towns across North America feature such historical villages. Examples include the Heritage Historical Village of New London, Wisconsin, which features five relocated and restored historic buildings, and the Historical Museum and Village of Sanibel, Florida, which includes seven building relocated from around the island (Figure 2.54). In cases where no historical buildings exist, history parks have been entirely reconstructed—for example, at Jamestown, Virginia, or Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Some of the larger re-created historical villages feature living history, which frequently includes both actors in period costume and skilled craftspeople practicing lost arts such as blacksmithing or candle making. Such sites can play an important role in developing and maintaining connections to the historic roots in contemporary cultural identities.

ELITIST LANDSCAPES

A characteristic of popular culture is the development of social classes. A small elite group—consisting of persons of wealth, education, and expensive tastes—occupies the top economic position in popular cultures. The important geographical fact about such people is that because of their wealth, desire to be around similar people, and affluent lifestyles, they can and do create distinctive cultural landscapes, often over fairly large areas.

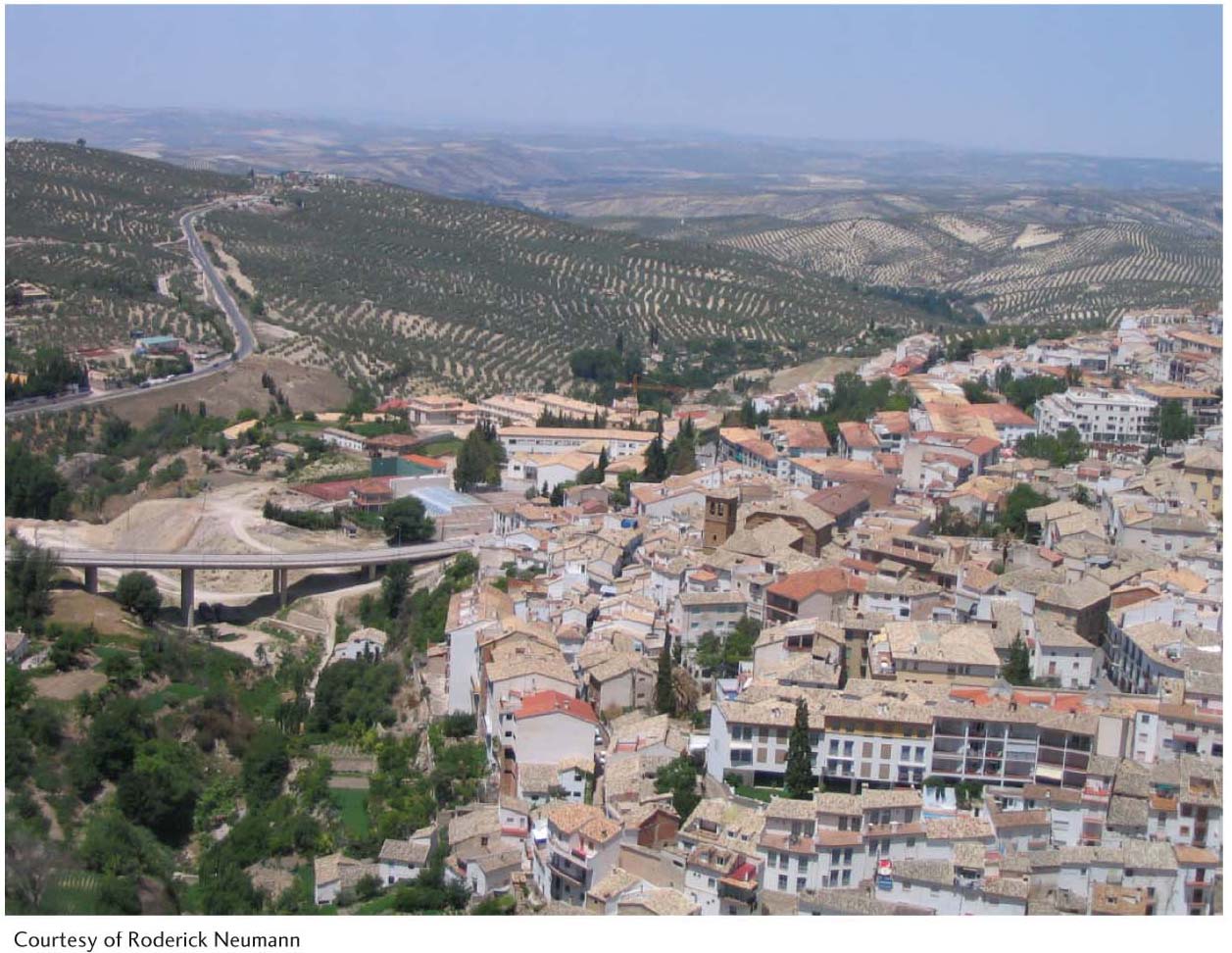

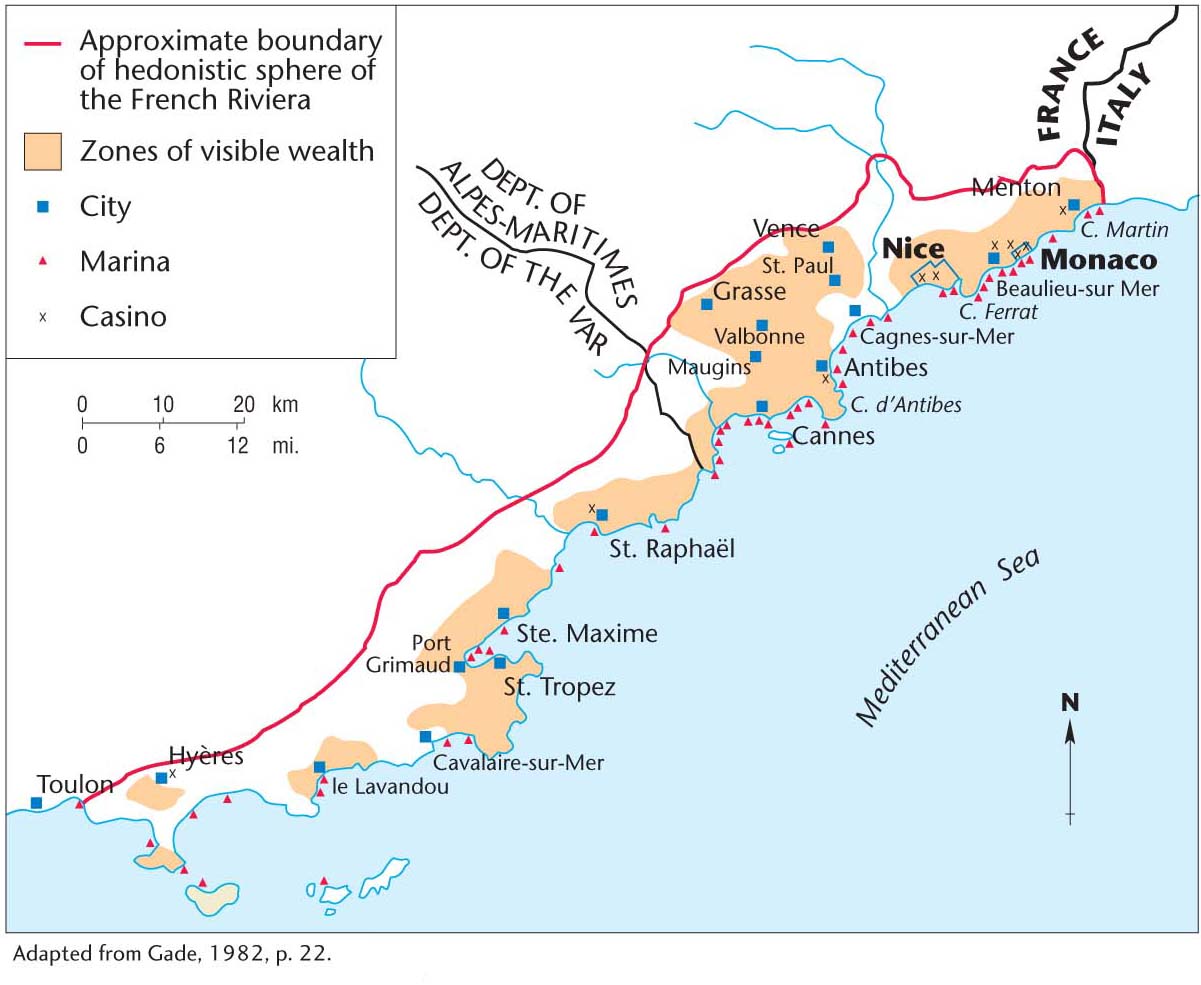

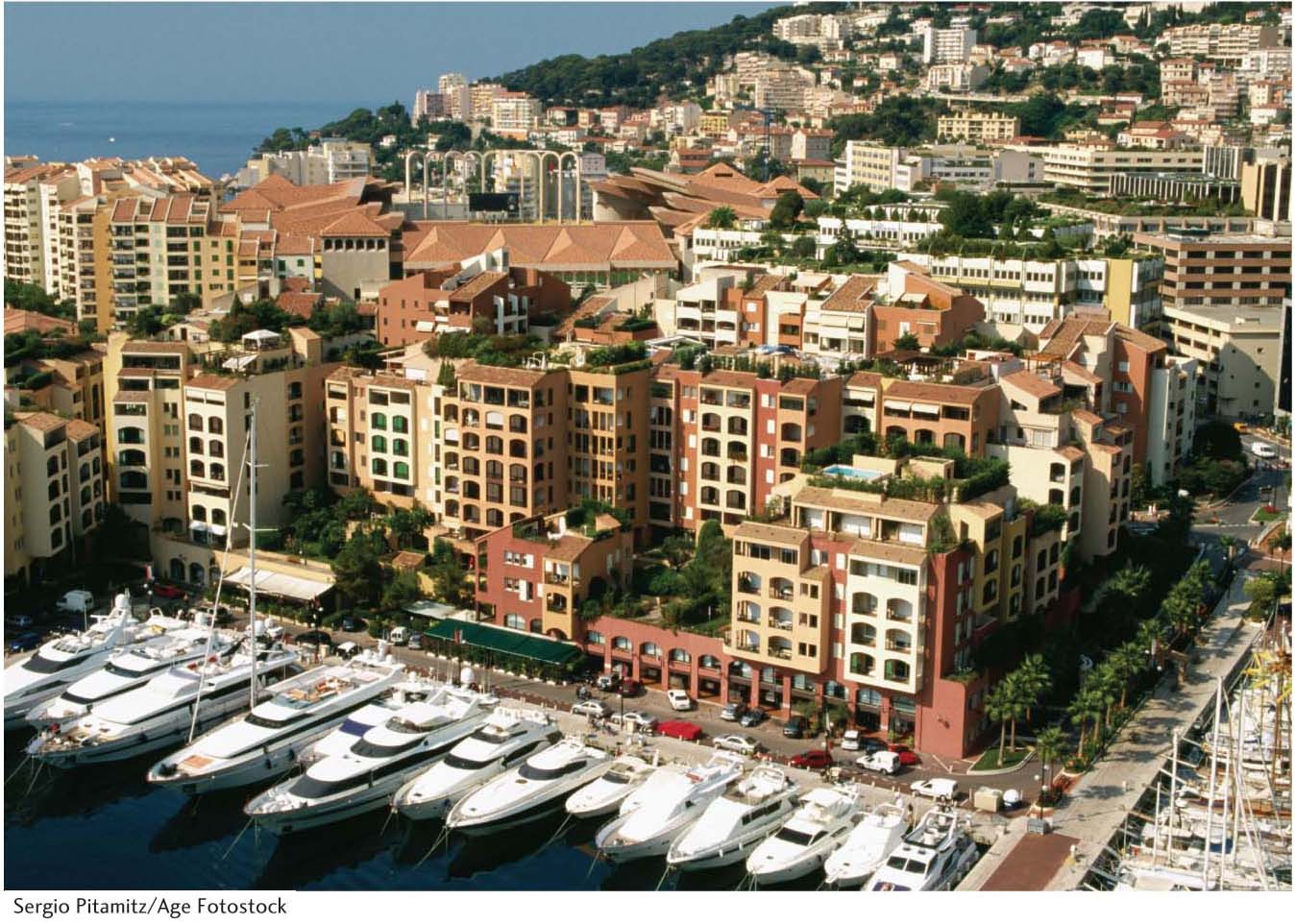

Daniel Gade, a cultural geographer, coined the term elitist space to describe such landscapes, using the French Riviera as an example (Figure 2.55). In that district of southern France, famous for its stunning natural beauty and idyllic climate, the French elite applied “refined taste to create an aesthetically pleasing cultural landscape” characterized by the preservation of old buildings and town cores, a sense of proportion, and respect for scale. Building codes and height restrictions, for instance, are strictly enforced. Land values, in response, have risen, making the Riviera ever more elitist, far removed from the folk culture and poverty that prevailed there before 1850. Farmers and fishers have almost disappeared from the region, though one need drive but a short distance, to Toulon, to find a working seaport. It seems, then, that the different social classes generated within popular culture become geographically segregated, each producing a distinctive cultural landscape (Figure 2.56).

85

The United States, too, offers elitist landscapes. The economic and cultural changes unfolding in the western part of the country offer a vivid example. This phenomenon is popularly known as the “Old West” versus the “New West.” The Old West is the historic regional economy and corresponding cultural landscapes based on cattle ranching, mining, and logging. Most Old Westerners worked as wage laborers in these extractive industries. The New West refers to an amenity-based economy that features luxury second homes, outdoor recreational resorts, and international art and film festivals. The New Westerners are affluent professionals who earned their money in distant cities and are attracted to the natural beauty of the mountainous West. They are creating elite landscapes in spaces formerly dedicated to resource extraction.

Geographers John Harner and Bradley Benz conducted a study in southern Colorado that perfectly demonstrates how New West landscapes emerge. They focused on the area surrounding Durango, a former mining town that is now a tourist mecca featuring a steam-train, gourmet restaurants, ski shops, and boutique clothing stores. There, they measured the growth of ranchettes, 35- to 70-acre private parcels of land too small to be economically productive or legally subdivided further. These new landholdings are created for wealthy New Westerners who vacation in or retire to their new luxury homes in the wide-open spaces.

86

Harner and Benz found that the number of ranchettes increased 67 percent from 1988 to 2008, which signals a huge influx of affluent migrants from the cities. Their study documented that the first ranchettes were constructed near the most desirable natural settings: streams and rivers, national parks and forests, and mountain vistas. The subdivision of large landholdings into ranchettes continued in a pattern of contiguous diffusion, gradually leveling out as the supply of amenity-rich spaces was exhausted.

Such fragmentation of landholdings and the corresponding creation of elite landscapes have been repeated across the western states many times over. Frequently, the process has led to clashes between newcomers and established residents. Geographers Peter Walker and Louise Fortmann studied the social conflicts emerging from the New West phenomenon in the foothills of California’s Sierra Nevada range. They determined that the most contentious political debates focused not on economic issues, but on cultural values expressed in landscape preferences. Affluent newcomers and established residents made different aesthetic judgments of landscape, and this was what drove efforts to gain political control over land-use decisions. The New West phenomenon highlights the relevance of cultural landscape to regional politics and economies.

THE AMERICAN POPULAR LANDSCAPE

In an article entitled “The American Scene,” geographer David Lowenthal attempted to analyze the visible impact of popular culture on the American countryside. Lowenthal identified the main characteristics of popular landscape in the United States, including the “cult of bigness”; the tolerance of present ugliness to achieve a supposedly glorious future; an emphasis on individual features at the expense of aggregates, producing a “casual chaos”; and the preeminence of function over form.

The American fondness for massiveness is reflected in structures such as the Empire State Building, the Pentagon, the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, and Salt Lake City’s Mormon Temple. Americans have dotted their cultural landscape with the world’s largest of this or that, perhaps in an effort to match the grand scale of the physical environment, which includes such landmarks as the Grand Canyon, the towering redwoods of California, and the Rocky Mountains.

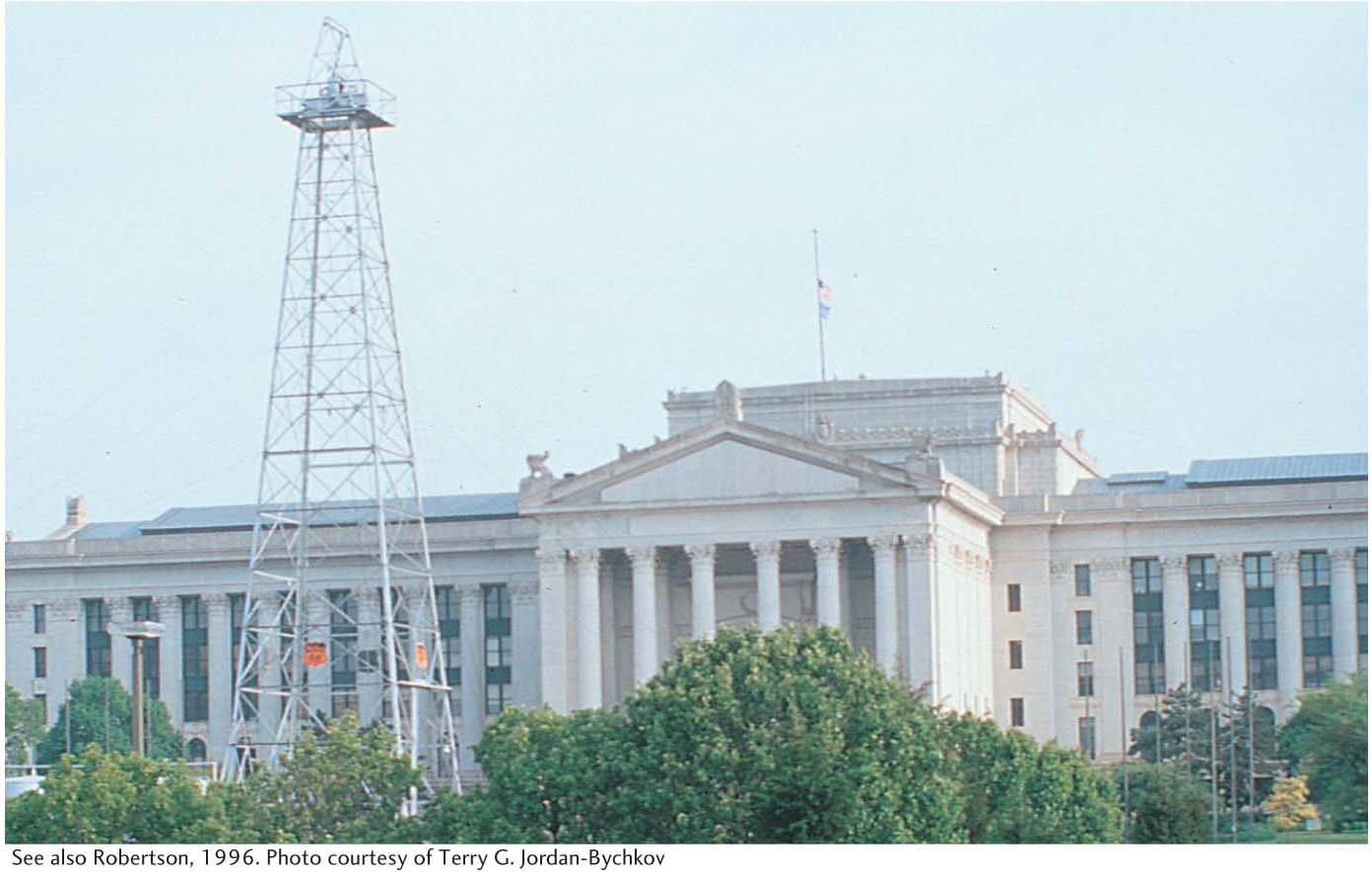

Americans, argues Lowenthal, tend to regard their cultural landscape as unfinished. As a result, they are “predisposed to accept present structures that are makeshift, flimsy, and transient,” resembling “throwaway stage sets.” Similarly, the hardships of pioneer life perhaps preconditioned Americans to value function more highly than beauty and form. The state capitol grounds in Oklahoma City are adorned with little more than oil derricks, standing above busy pumps drawing oil and the wealth that comes with it from the Sooner soil—an extreme but revealing view of the American landscape (Figure 2.57).

In summary, American popular culture seems to have produced a built landscape that stresses bigness, utilitarianism, and transience. Sometimes these are opposing trends, as in the case of many of the massive structures previously cited, which are clearly built to last. Sometimes the trends mesh, as in the recent explosion of “big box” retail chains (Figure 2.58). These giant retail buildings are no more than oversized metal sheds that one can easily imagine being razed overnight, only to be replaced by the next big thing.

87