GLOBALIZATION

3.3

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Discuss theories of population growth and control and how these have changed over time.

One of the great debates today involves the population of the Earth. How many people can the Earth support? Should humans limit their reproduction, and who should decide? There are no precise numbers involved in this debate, but these questions are so hotly contested because addressing them in a conscientious way may well determine the long-term fate of the human race.

POPULATION EXPLOSION?

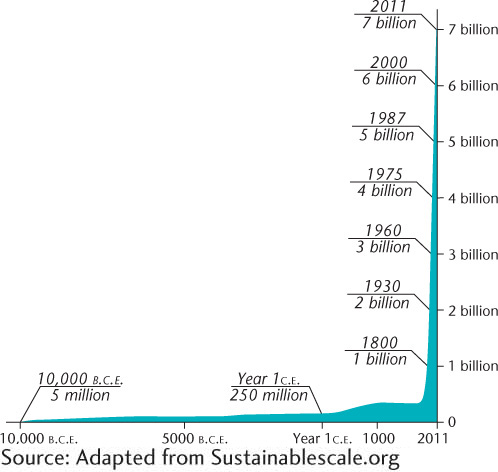

One of the fundamental issues of the modern age is the population explosion: a dramatic increase in world population since 1900 (Figure 3.20). The crucial element triggering this explosion has been a steep decline in the death rate, particularly for infants and children, in most of the world, without an accompanying universal decline in fertility. At one time in traditional cultures, only two or three offspring in a family of six to eight children might live to adulthood, but when improved health conditions allowed more children to survive, the cultural norm encouraging large families persisted.

population explosion

The rapid, accelerating increase in world population since about 1650 and especially since 1900.

Until very recently, the number of people in the world has been increasing geometrically, doubling in shorter and shorter periods of time. It took from the beginning of human history until 1800 c.e. for the Earth’s population to grow to 1 billion people. But from 1800 to 1930, it grew to 2 billion, and in only 45 more years it doubled again (Figure 3.21). The overall effect of even a few population doublings is astonishing. As an illustration of a simple geometric progression, consider the following legend. A king was willing to grant any wish to the person who could supply a grain of wheat for the first square of his chessboard, two grains for the second square, four for the third, eight for the fourth, and so on. To cover all 64 squares and win, the candidate would have had to present a cache of wheat larger than today’s worldwide wheat crop. Looking at the population explosion in another way, it is estimated that 107 billion humans have lived in the entire 200,000-year period since Homo sapiens originated. Of these, 7 billion (roughly 7 percent) are alive today.

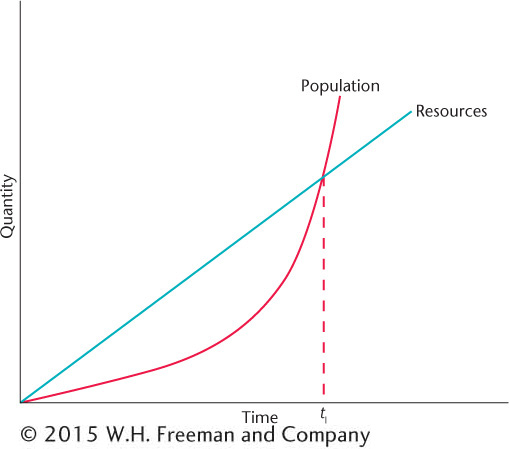

116

Some scholars foresaw long ago that an ever-increasing global population would eventually present difficulties. The most famous pioneer observer of population growth, the English economist and cleric Thomas Malthus, published An Essay on the Principle of Population—known as the “dismal essay”—in 1798. He believed that the human ability to multiply far exceeded our ability to increase food production. Consequently, Malthus maintained that “a strong and constantly operating check on population” would necessarily act as a natural control on numbers. Malthus regarded famine, disease, and war as the inevitable outcome of the human population’s outstripping the food supply (Figure 3.22). He wrote, “Population, when un-checked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence only increases in an arithmetical ratio. A slight acquaintance with numbers will show the immensity of the first power in comparison of the second.”

The adjective Malthusian entered the English language to describe the dismal future Malthus foresaw. Being a cleric as well as an economist, however, Malthus believed that if humans could voluntarily restrain the “passion between the sexes,” they might avoid their otherwise miserable fate.

Malthusian

Those who hold the views of Thomas Malthus, who believed that overpopulation is the root cause of poverty, illness, and warfare.

OR CREATIVITY IN THE FACE OF SCARCITY?

But, was Malthus right? From the very first, his ideas were controversial. The founders of communism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, blamed poverty and starvation on the evils of capitalist society. Taking this latter view might lead one to believe that the miseries of starvation, warfare, and disease are more the result of maldistribution of the world’s wealth than of overpopulation. Indeed, severe food shortages in several regions point to precisely this issue of inequitable food distribution and its catastrophic consequences.

Malthus did not consider that when faced with complex problems such as scarce food supplies, human beings are highly creative. This has led critics of Malthus and his modern-day followers to point out that although the global population has doubled three times since Malthus wrote his essay, food supplies have doubled five times. Scientific innovations such as the green revolution have led to food increases that have far outpaced population growth (see Chapter 8). Other measures of well-being, including life expectancy, air quality, and average education levels, have all improved, too. Some of Malthus’s critics, known as cornucopians, argue that human beings are, in fact, our greatest resource and that attempts to curb our numbers misguidedly cheat us out of geniuses who could devise creative solutions to our resource shortages. Modern-day followers of Malthus, known as neo-Malthusians, counter that the Earth’s support systems are being strained beyond their capacity by the widespread adoption of wasteful Western lifestyles.

cornucopians

Those who believe that science and technology can solve resource shortages. In this view, human beings are our greatest resource rather than a burden to be limited.

neo-Malthusians

Modern-day followers of Thomas Malthus.

117

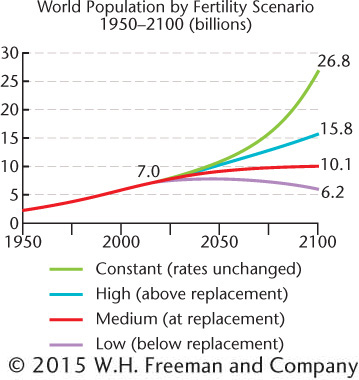

The fact is that the world’s population is growing more slowly than before. The world’s TFR has fallen to 2.47; one demographer has declared that “the population explosion is over”; and Figure 3.21 depicts a leveling-off of the global population at about 11 billion by the year 2100, suggesting that the world’s current “population explosion” is merely a stage in a global demographic transition. Relatively stable population totals worldwide, however, mask the population declines and aging of the population structure already under way in some regions of the world.

It is difficult to speculate about the state of the world’s population beyond the year 2050. What is clear, however, is that the lifestyles we adopt will affect how many people the Earth can ultimately support. In particular, whether wealthy countries continue to use the amount of resources they currently do, and whether developing countries decide to follow a Western-style route toward more and more resource consumption, will significantly determine whether we have already overpopulated the planet.

THE RULE OF 72

A handy tool for calculating the doubling time of a population is called the Rule of 72: take a country’s rate of annual increase, expressed as a percent, and divide it into the number 72. The result is the number of years a population, growing at a given rate, will take to double.

For example, the natural annual growth of the United States in 2013 was 0.6 percent. Dividing 72 by 0.6 yields 120, which means that the population of the United States will double every 120 years. This does not, however, factor in the relatively high levels of immigration experienced by the United States, which will cause its population to double faster than every 120 years.

What about countries with faster rates of growth? Consider Guatemala, which is growing at 2.1 percent per year. Doing the math, we find that Guatemala’s population is doubling every 34 years!

Percentages such as 0.6 or 2.1 don’t sound like such high rates. If we were discussing your bank account rather than the populations of countries, you would hope that your money would double more quickly than every 34 years! (Incidentally, you can apply the Rule of 72 to your bank account or to any other figure that grows at a steady annual rate.) You may be tempted to say, “Look, there are only 14 million people in Guatemala, so it doesn’t really matter if its population is doubling quickly. What really matters is that at an annual increase of 1.3 percent, India’s 1.2 billion people will double to 2.4 billion in 55 years, and China’s 1.35 billion will double almost as fast as the U.S. population—every 146 and 137 years, respectively —but that will add another 1.35 billion to the world’s population, more than four times what the United States will add by doubling!”

This assessment is partly right and partly wrong, depending on your vantage point. Viewed at the global scale, it does indeed make a significant difference when China’s or India’s population doubles. But if you are a resident of Guatemala or an official of the Guatemalan government, a doubling of your country’s population every 34 years means that health care, education, jobs, fresh water, and housing must be supplied to twice as many people every 34 years. As mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, the scale at which population questions are asked is vital for the answers that are given.

POPULATION CONTROL PROGRAMS

Though the debates may occur at a global scale, most population control programs are devised and implemented at the national level. When faced with perceived national security threats, some governments respond by supporting pronatalist programs designed to increase the population. Labor shortages in Nordic countries have led to incentives for couples to have larger families. Most population programs, however, are antinatalist: they seek to reduce fertility. Needless to say, this is an easier task for a nonelected government to carry out because limiting fertility challenges traditional gender roles and norms about family size.

118

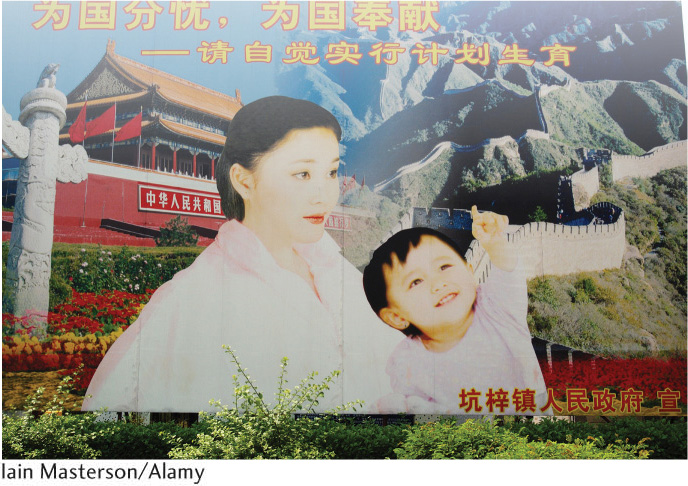

Although China certainly is not the only country that has sought to limit its population growth, its so-called one-child policy provides the best-known modern example. Mao Zedong, the longtime leader of the People’s Republic of China (1949-1976), did not initially discourage large families in the belief that “every mouth comes with two hands.” In other words, he believed that a large population would strengthen the country in the face of external political pressures. He reversed his position in the 1970s when it became clear that China faced resource shortages as a result of its burgeoning population. In 1980 the one-child-per-couple policy was adopted. With it, Chinese authorities sought not merely to halt population growth but, ultimately, to decrease the national population. All over China today one sees billboards and posters admonishing the citizens that “one couple, one child” is the ideal family (Figure 3.23). Violators face huge monetary fines, cannot request new housing, lose the rather generous benefits provided to the elderly by the government, forfeit their children’s access to higher education, and may even lose their jobs. Late marriages are encouraged. In response, between 1970 and 1980, the TFR in China plummeted from 5.9 births per woman to only 2.7, then to 2.2 by 1990, 2.0 by 1994, 1.7 by 2007, and 1.5 by 2013 (see Figure 3.3). The Chinese government claims that 400 million fewer births have occurred over the lifetime of the policy.

China achieved one of the greatest short-term reductions of birth rates ever recorded, thus proving that cultural changes can be imposed from above, rather than simply waiting for them to diffuse organically. In recent years, the Chinese population control program has been less rigidly enforced as economic growth has eroded the government’s control over the people. This relaxation has allowed more couples to have two children instead of one; however, the increase in economic opportunity and migration to cities have led some couples to have smaller families voluntarily. Because of China’s population size, its actions will greatly affect the global context as well as its own national one (see Subject to Debate for a discussion of the gender implications of strict population control policies).