CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

3.5

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Analyze the imprint of demographic factors on the cultural landscape.

Population geographies are visible in the landscapes around us. The varied densities of human settlements and the shapes these take in different places provide clues to the intertwined cultural and demographic strategies implemented in response to diverse local factors. These clues are evident wherever people have settled, be they urban, suburban, or rural locations. Less visible, but no less important, factors are also at work on and throughout the cultural landscape. In this final part of the chapter, we examine the diverse, and often creative, ways in which different places are organized spatially in order to accommodate the populations that live there.

124

DIVERSE SETTLEMENT TYPES

Human settlements range in density from the isolated farmsteads found in some rural areas to the teeming streets of megacities such as Kolkata, India (see Seeing Geography). The size and pattern of human settlements depend, in part, on the size and needs of the population to be accommodated. Small rural populations and those engaged in subsistence farming don’t inhabit large, dense cities. Nomadic peoples require dwellings that can be easily packed up and moved, and they tend to have few household possessions (Figure 3.30). On the other end of the spectrum, dense cities make more sense for populations employed in the service and information sectors. These people benefit from being as close as possible to their jobs, and higher densities—at least in theory—reduce commuting distances. People in postindustrial societies also tend to have smaller families, which can be more easily accommodated in apartments (Figure 3.31).

But, there is also a significant cultural aspect at work, such that similar populations may live in settlements that look and feel vastly different from each other. Take rural settlements, for instance. In many parts of the world, farming people group themselves together in clustered settlements called farm villages. These tightly bunched settlements vary in size from a few dozen inhabitants to several thousand. Contained in the village farmstead are the house, barn, sheds, pens, and garden. The fields, pastures, and meadows lie out in the country beyond the limits of the village, and farmers must journey out from the village each day to work the land.

farm villages

Clustered rural settlements of moderate size, inhabited by people who are engaged in farming.

farmstead

The center of farm operations, containing the house, barn, sheds, and livestock pens.

125

Farm villages are the most common form of agricultural settlement in much of Europe, in many parts of Latin America, in the densely settled farming regions of Asia (including much of India, China, and Japan), and among the sedentary farming peoples of Africa and the Middle East.

In many other parts of the world, the rural population lives on dispersed, isolated farmsteads, often some distance from the nearest neighbors (Figure 3.32). These dispersed rural settlements grew up mainly in Anglo America, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa—that is, in the lands colonized by emigrating Europeans.

Why do so many farm people settle together in villages? Historically, the countryside was unsafe, threatened by roving bands of outlaws and raiders. Farmers could better defend themselves against such dangers by grouping together in villages. In many parts of the world, the populations of villages have grown larger during periods of insecurity and shrunk again when peace returned. Many farm villages occupy the most easily defended sites in their vicinity.

Various communal ties strongly bind villagers together. Farmers linked to one another by blood relationships, religious customs, communal landownership, or other similar bonds usually form clustered villages. Mormon farm villages in the United States provide an excellent example of the clustering force of religion. Communal or state ownership of the land—as in China and parts of Israel—encourages the formation of farm villages.

The conditions encouraging dispersed settlement are precisely the opposite of those favoring village development. These include peace and security in the countryside, eliminating the need for defense; colonization by individual pioneer families rather than by socially cohesive groups; private agricultural enterprise, as opposed to some form of communalism; and well-drained land where water is readily available. Most dispersed farmsteads originated rather recently, dating primarily from the colonization of new farmland in the past two or three centuries.

LANDSCAPES AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE

Population change in a place can occur rapidly or more slowly over time. Rapid depopulation can come about as the result of sudden catastrophic events, such as natural disasters, disease epidemics, and warfare (Figure 3.33). Or depopulation can take place at a slower pace. For example, places may lose population over time because of the gradual out-migration of people in search of opportunities elsewhere, as a cumulative result of declining fertility rates, or as we saw in the previous section in response to climate change.

depopulation

A decrease in population that sometimes occurs as the result of sudden catastrophic events, such as natural disasters, disease epidemics, and warfare.

126

Populations can also grow in more or less rapid fashions. A place might experience an abrupt influx of people who have been displaced from other areas. Population increases commonly occur more gradually, as the result of demographic improvements such as longer life spans or lower infant mortality rates, or the accumulation of steady streams of immigrants to attractive areas over time.

Depopulation in one area and population increase in another are often linked processes. For instance, you could easily envision a scenario in which the environmental refugees exiting one place suddenly flood into a neighboring area. As a longer-term example, you could equally well imagine how broad economic changes or technological innovations could lead to regional population shifts whereby some areas become depopulated and others gain population.

Indeed, shifting economic and technological conditions have influenced the demographic landscape in profound ways. The process of industrialization during the past 200 years has caused the greatest voluntary relocation of people in world history. Within industrial nations, people moved from rural areas to cluster in manufacturing regions (see Chapter 10). Agricultural changes have also influenced population density. For example, the complete mechanization of cotton and wheat cultivation in mid-twentieth-century America allowed those crops to be raised by a much smaller labor force (see Chapter 8). As a result, profound depopulation occurred, to the extent that many small towns serving these rural inhabitants ceased to exist.

Regardless of the reasons, population changes must be accommodated, and these adaptations are invariably reflected in the cultural landscape.

Depopulation in History: Ancient Rome There are as many theories accounting for the decline of the Roman Empire as there are historians theorizing about it. Lead poisoning, overextension of the empire’s reach, conquest by Germanic tribes, and at least 200 other theories have been proposed.

Rome, the empire’s capital city, suffered this process acutely. For nearly a millennium, Rome had been the world’s wealthiest, most powerful, and most populous city (Figure 3.34). At the close of the first century c.e., Rome’s population surpassed 1 million. As the Roman Empire’s economic, political, and military might waned across the third, fourth, and fifth centuries, the demographic balance shifted as well. Under the emperor Constantine in 330 c.e., the empire was split into eastern and western halves, and its capital was relocated to Constantinople (now Istanbul, in modern-day Turkey).

As barbarian invasions further weakened the divided empire, Rome’s physical infrastructure—its famed roads, bridges, aqueducts, and monumental buildings—crumbled, as did its impressive administrative infrastructure. With no access to former amenities, from running water to educational opportunities, Rome’s population had shrunk to around 20,000 by 550 c.e. The Roman landscape had become a ghost of its former glory: dilapidated, uninhabited, and in ruins (see Figure 3.34).

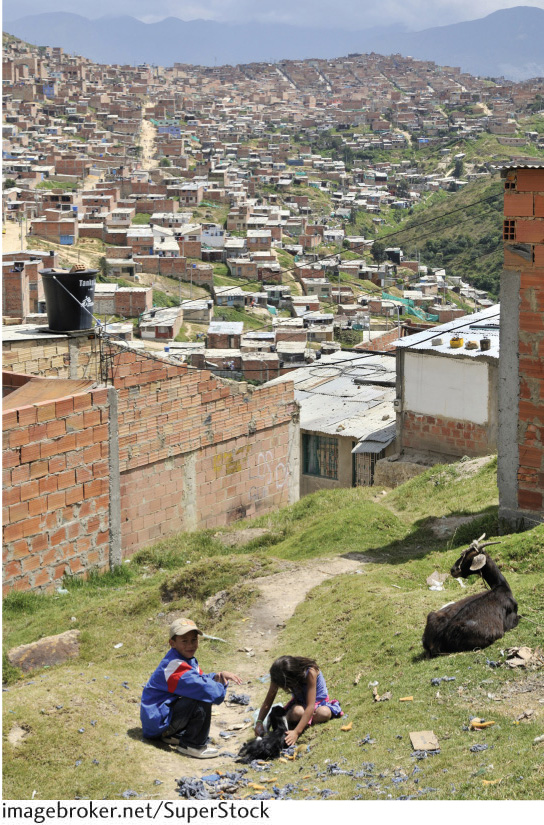

Bogotá Rising Dilapidated-looking landscapes can result from population decline, as the previous example of ancient Rome illustrates, but they can also arise from rapid population influx. Many of the world’s shantytowns exemplify the sort of chaotic landscape that can result from rapid population increases. Los Altos de Cazucá, a neighborhood in the Colombian capital of Bogotá, is but one example. In this case, the population influx comes mostly from people arriving in the capital after being displaced by armed conflict in the countryside.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that, by 2012, there were 28.8 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) due to armed conflict worldwide. Colombia is one of the globe’s hotspots for IDPs and has the highest number of IDPs of any country in the world. Colombia’s estimated 5.8 million IDPs have been uprooted largely as the result of ongoing civil warfare between the paramilitary group known as the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) and government forces bent on eradicating them. The UNHCR has identified this as the “worst humanitarian crisis in the western hemisphere.”

127

Colombia’s armed conflict has depopulated the rural areas where it occurs, forcing its victims into the cities. Terrorized, landless, and impoverished, the mainly indigenous and Afro-Colombian IDPs settle in the outskirts of cities like Colombia’s capital, Bogotá.

Los Altos de Cazucá is one of the settlements inhabited by Colombia’s internally displaced persons (Figure 3.35). Known as shantytowns, areas like Los Altos de Cazucá arise for different reasons, but they exist in all large cities throughout the developing world. Housing is constructed by the residents themselves, using found materials like cardboard, tin panels, and old tires. Some shantytowns are located far away from downtown areas where wealthy people reside and where jobs are, while others are literally pressed up against wealthier neighborhoods (Figure 3.36).

128

Most shantytowns arise spontaneously, in order to address population influx to cities that lack the resources to plan systematically for rapid growth. But, are shantytowns temporary, disappearing as their residents become incorporated into city life? Hardly. Instead, shantytowns gradually become part of the urban fabric. Indeed, most of the spatial expansion of Latin American cities like Bogotá occurs precisely thanks to growth of the shantytowns surrounding them. Over time, the dwellings are constructed of more-permanent materials such as concrete blocks. Roads are paved and running water installed. Power and phone lines are extended. The once-temporary areas slowly become visually, economically, and culturally integrated into the permanent fabric of the city. New shantytowns then arise beyond their borders, to accommodate recent arrivals.

World Heritage Site: Pico Island Vineyard

World Heritage Site

Pico Island Vineyard

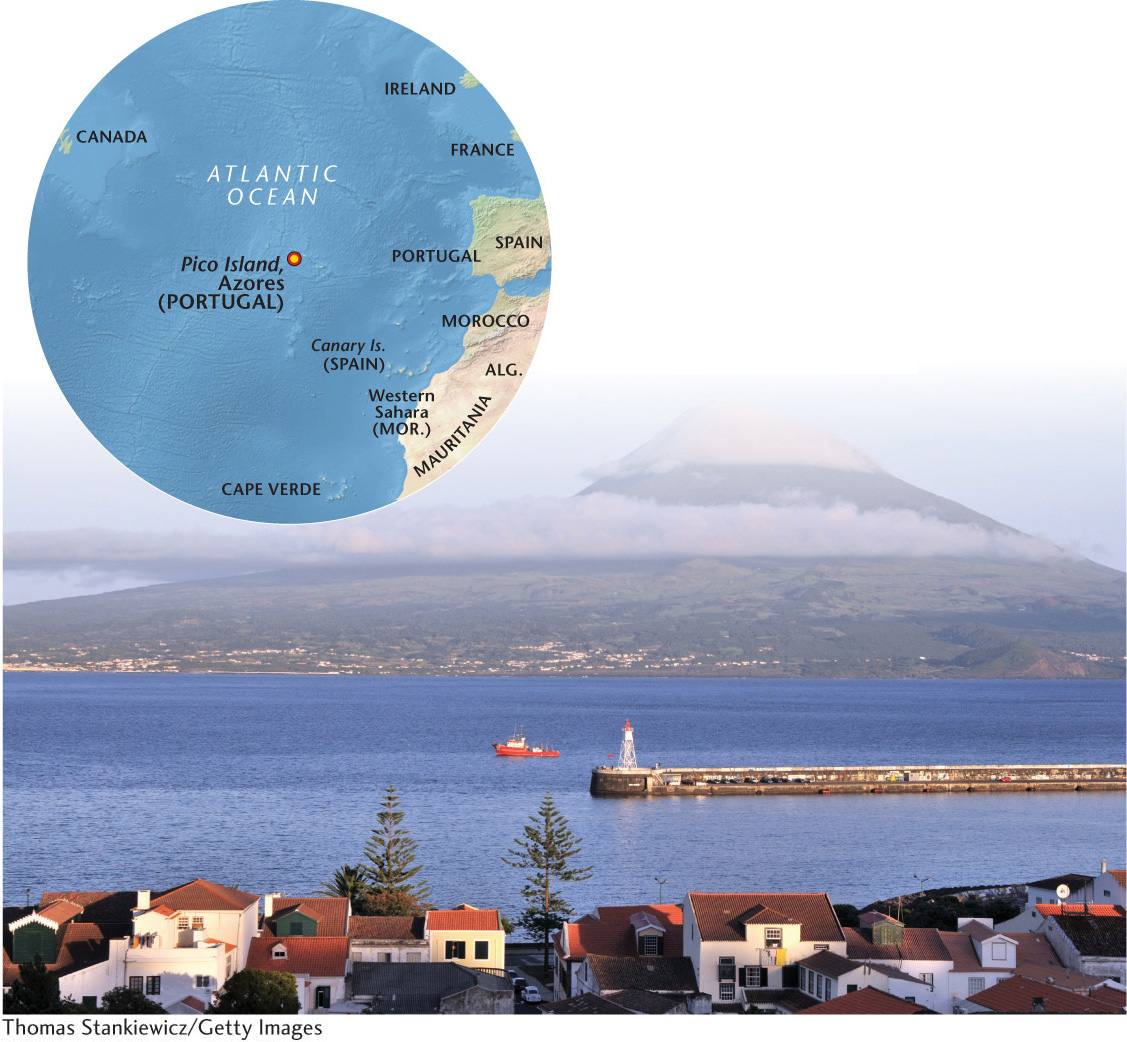

Pico Island is the second largest island in the Azores, a chain of nine volcanic islands. Politically a part of Portugal, the islands are located some 950 miles west of Portugal, in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. Pico Island is noted for its vineyard culture, established in the 1500s, which exemplifies the isolated farmstead settlement.

◼ Pico Island consists of 987 hectares (40,515 square feet) of volcanic rock whose man-made landscape has been shaped entirely for small-scale agriculture; namely, growing grapes and processing them into wine (viniculture).

◼ The island remained uninhabited until 1439, when the first Portuguese settlers arrived. Initially, they were cattle herders, but winemaking was introduced from the mainland a few decades later, with Portuguese Franciscan and Carmelite religious orders improving its techniques in the 1500s. Winemaking continued to be the island’s mainstay until the mid-1800s, when the grape vines became afflicted by grape mildew and phyllorexa (plant diseases). Today, wine production has experienced a resurgence, although the sweet Verdelho wine exported to European nobility in past centuries is hard to find because the island’s small size limits total production.

◼ With a population of just over 15,000 people, Pico Island counts some cities—the capital Madalena being the largest with 6000 inhabitants—but the majority of its population lives in small farm villages and port towns.

129

THE WALLS: The viniculture landscape of Pico Island is unique and ingenious. The island has mild year-round temperatures and adequate rain, both of which are conducive to growing wine grapes. But the island is constantly buffeted by strong winds and sea surges that are harmful to grape vines. In response, islanders used volcanic basalt rock to construct walls along the coastline, which enclose small plots of land used to grow grapes. The walls protect the fragile plants from the wind and sea water, and support them as they grow. The resulting landscape is one of many small interlocking rectangular plots, called currais, bounded by dark-colored basalt rock walls. UNESCO has deemed this an “extraordinarily beautiful man-made landscape of small, stone-walled fields.”

◼ Vine cultivation is done entirely by hand, rather than using farm machinery. This is possible because of the small scale of wine production on the island. In addition, the rocks used to construct the walls were stacked meticulously by hand: no mortar was used.

◼ Buildings constructed to support winemaking and the people engaged in it include cellars, warehouses, churches, ports, houses, and wells. The settlements are small and the architecture distinctive.

TOURISM: The island’s natural features as well as its historic industries attract a small but growing number of tourists.

◼ Pico is “the mountain island” of the Azores, dominated by a volcanic cone rising nearly 8000 feet above sea level. Hiking to the crater at the top of the dormant volcano takes a full day and is quite challenging.

◼ Whaling, officially banned by the European Union in the 1980s, was Pico Island’s main industry for a period of time. Today, whale watching is one of the island’s primary tourist activities.

◼ Pico Island has received an international award for its efforts to promote sustainable tourism (tourism that results in low impact to the environment and local culture).

◼ Pico Island is a beautiful expression of the balance forged between nature and man in isolated conditions.

◼ The small, geometric basalt-walled plots are ingenious constructions that allow for the successful cultivation of wine grapes in a harsh environment.

◼ Placed on the list of World Heritage Sites in 2004, Pico Island has a small but growing tourism industry.

130