NATURE-CULTURE

5.4

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Analyze the diverse ways in which ethnic and racial groups interact with the natural environment, and discuss how these groups may be protected, or made more vulnerable.

Ethnicity is very closely linked to the nature-culture theme. The interplay between people and physical environment is often evident in the pattern of ethnic culture regions, in ethnic migration, and in the persistence or even survival of ethnic and racialized groups. Ethnicity and race are sometimes also linked to the environment in harmful ways, particularly when the places they inhabit become the targets of pollution.

CULTURAL PREADAPTATION

For those ethnic groups created by migration or relocation diffusion, the concept of cultural preadaptation provides an interesting approach. Cultural preadaptation involves a set of adaptive traits possessed by a group in advance of migration that gives them the ability to survive and a competitive advantage in colonizing the new environment. Most often, preadaptation occurs in groups migrating to a place that is environmentally similar to the one they left behind. The adaptive strategy they had pursued before migration works reasonably well in the new home.

cultural preadaptation

A complex of adaptive traits and skills possessed in advance of migration by a group, giving it survival ability and competitive advantage in occupying the new environment.

The preadaptation may be accidental, but in some cases, the immigrant ethnic group deliberately chooses a destination area that physically resembles their former home. In Africa, the Bantu expansion mentioned in Chapter 4 was probably initially driven by climate change and expansion of the Sahara (see Figure 4.5). The Bantu spread south and west in search of forested lands similar to those they had previously inhabited. But, their progress southward was finally inhibited because their agricultural techniques and cattle were not adapted to the drier Mediterranean climate of southern Africa.

Such ethnic niche-filling has continued to the present day. Cubans have clustered in southernmost Florida, the only part of the U.S. mainland to have a tropical savanna climate identical to that in Cuba, and many Vietnamese have settled as fishers on the Gulf of Mexico, especially in Texas and Louisiana, where they could continue their traditional livelihood. Yet, historical and political patterns, as well as the factors driving chain migration discussed earlier, are also at work in these contemporary patterns of ethnic clustering. They act to temper the influence of the physical environment on ethnic residential selection, making it only one of many considerations.

This deliberate site selection by ethnic immigrants represents a rather accurate environmental perception of the new land. As a rule, however, immigrants tend to perceive the ecosystem of their new home as more like that of their abandoned native land than is actually the case. Their perceptions of the new country emphasize the similarities and minimize the differences. Perhaps the search for similarity results from homesickness or an unwillingness to admit that migration has brought them to a largely alien land. Perhaps growing to adulthood in a particular kind of physical environment inhibits one’s ability to perceive a different ecosystem accurately. Whatever the reason, the distorted perception occasionally caused problems for ethnic farming groups (for examples, see Chapter 8). A period of trial and error was often necessary to come to terms with the New World environment. Sometimes crops that thrived in the old homeland proved poorly suited to the new setting. In such cases, cultural maladaptation is said to occur.

cultural maladaptation

Poor or inadequate adaptation that occurs when a group pursues an adaptive strategy that, in the short run, fails to provide the necessities of life or, in the long run, destroys the environment that nourishes it.

HABITAT AND THE PRESERVATION OF DIFFERENCE

Certain habitats may act to shelter and protect ethnically or racially distinct populations. The high altitudes and rugged terrain of many mountainous regions make these areas relatively inaccessible and thus can provide refuge for minority populations while providing a barrier to outside influences. As we saw in the previous chapter on language, mountain dwellers sometimes speak archaic dialects or preserve their unique tongues thanks to the refuge provided by their habitat. In more general terms, the ways of life—including language—associated with ethnic distinctiveness are often preserved by a mountainous location.

206

The ethnic patchwork in the Caucasus region, for example, persists thanks in no small measure to the mountainous terrain found there. As Figure 5.22 shows, distinct groups occupy the rugged landscape of valleys, plateaus, peaks, foothills, steppes, and plains in this region. Religions and languages overlap in complex ways with ethnic identities and are made even more confounding by the geopolitical boundaries in the region. Thus, although this is one of the most ethnically diverse places on Earth, the Caucasus region has seen more than its fair share of conflict as well, much of it ethnically motivated.

207

Islands, too, can provide a measure of isolation and protection for ethnically or racially distinct groups. The Gullah, or Geechee, people are descendants of African slaves brought to the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to work on plantations. Many of their nearly 10,000 descendants today inhabit the coastal islands of South Carolina, Georgia, and north Florida. Their island location has allowed much of the original African cultural roots to be preserved, so much so that the Gullah are sometimes called the most African American community in the United States. Today, as the tourist industry sets it sights on developing these coastal islands, and as Gullah youth migrate elsewhere in search of opportunity, the survival of this unique culture is in question.

ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM

Not only people but also the places where they dwell can be labeled by society as minority. And, it is a fact that, although belonging to a racial or ethnic minority group does not necessarily lead to poverty, the two often go hand-in-hand. In spatial terms, being poor frequently equals having the last and worst choice of where to live. In cities, that means impoverished and racialized minorities often reside in run-down, ecologically precarious, or peripheral places that no one else wants to inhabit (Figure 5.23). In rural areas, racialized and indigenous minorities work the smallest and least fertile lands, or—more commonly—they work the plots of others, having become dispossessed of their own lands.

Environmental racism refers to the likelihood that a racialized minority population inhabits a polluted area. As Robert Bullard asserts, “Whether by conscious design or institutional neglect, communities of color in urban ghettos, in rural ‘poverty pockets,’ or on economically impoverished Native American reservations face some of the worst environmental devastation in the nation.” In the United States, Hispanics, Native Americans, blacks, and poor people of all races are more likely than wealthier whites to reside in places where toxic wastes are dumped, polluting industries are located, or environmental legislation is not enforced. Inner-city populations, which in many U.S. cities are disproportionately made up of minorities and the poor, occupy older buildings contaminated with asbestos and toxic lead-based paints. Farmworkers, who in the United States are disproportionately Hispanic, are exposed to high levels of pesticides, fertilizers, and other agricultural chemicals. Native American reservation lands are targeted as possible sites for disposing of nuclear waste.

environmental racism

The targeting of areas where ethnic or racial minorities, immigrants, and/or poor people live with respect to environmental contamination or failure to enforce environmental regulations.

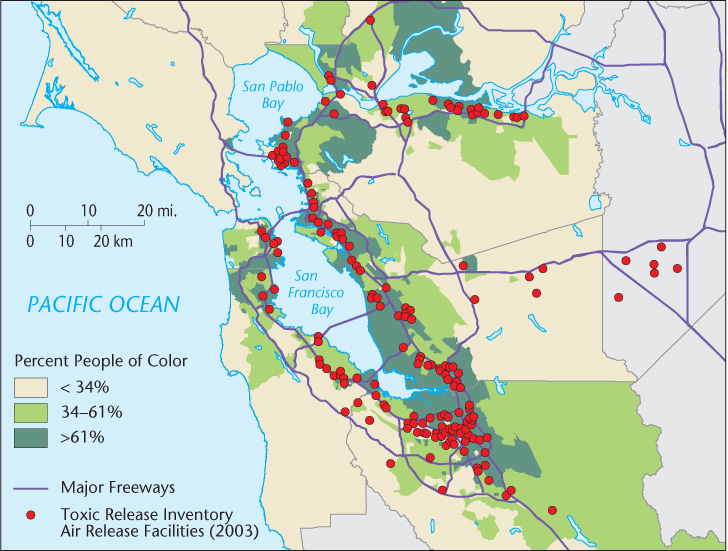

There is an overlap of nonwhite populations and toxic release facilities that is difficult to explain away as simply a random coincidence (Figure 5.24). Rather, areas such as the city of South Gate, located in Los Angeles County, have seen contaminating industries and activities purposely located in what is today a neighborhood composed of more than 90 percent Latino residents. In its early days, South Gate was inhabited mostly by white non-Hispanics. From its founding in 1923 until the 1960s, some of the largest U.S. polluters located their operations there: Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, A.R. Maas Chemical Company, Bethlehem Steel, Alcoa Aluminum, and hundreds of smaller operations were allowed to set up shop in a period when few were aware of the health consequences of their activities. These industries attracted labor arriving from Mexico. During this period, the neighborhood was encircled by four major freeways and a flight path was routed overhead. Pollution resulting from the transportation-related fossil fuels added to the industrial waste in this community. As the deleterious health impacts of these environmental factors became more evident, white residents began to move away, being replaced by Hispanics, some 30 percent of whom are believed to be recent undocumented immigrants. Although many of the industries are now closed, their contaminants remain in the soil and water.

208

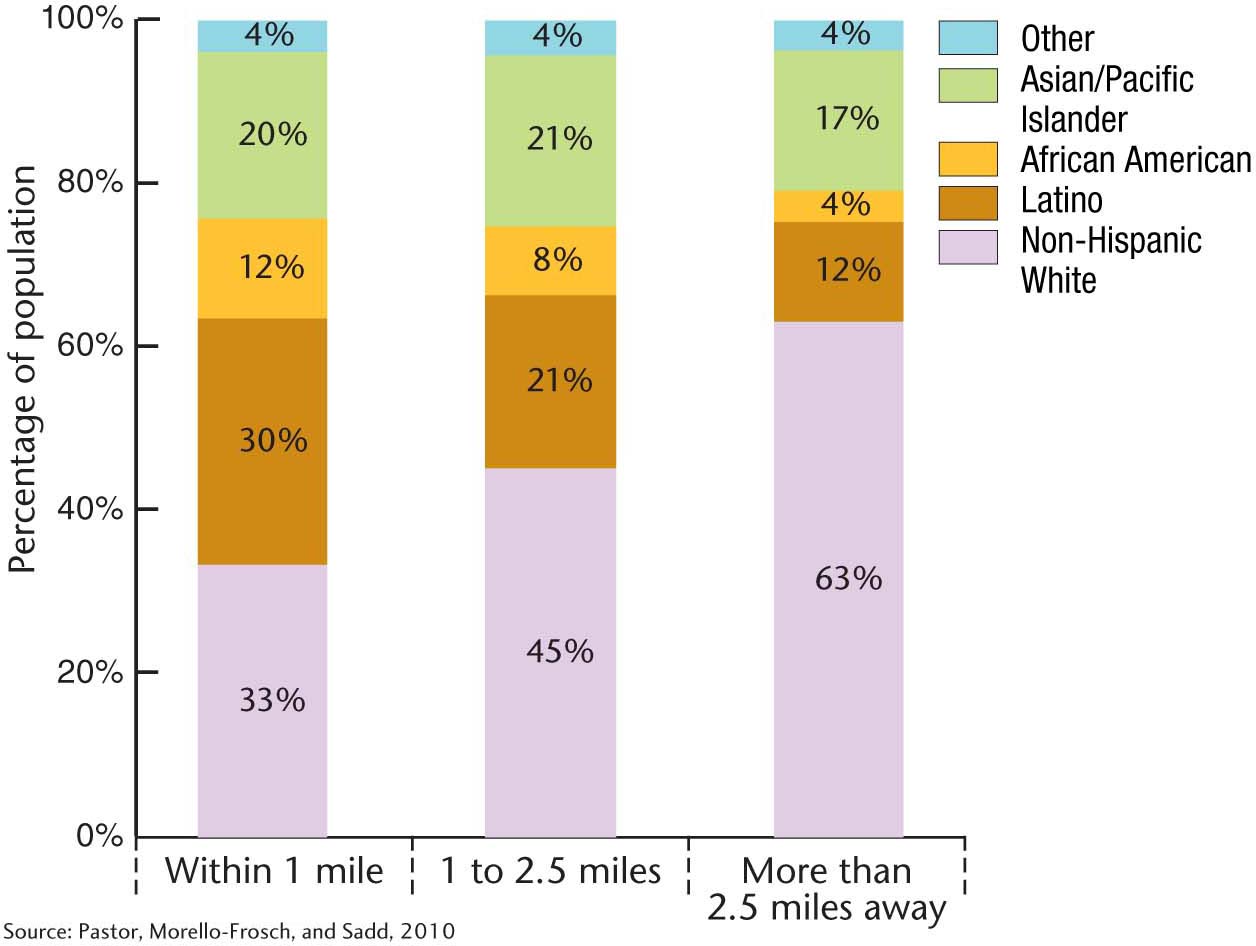

Today, as well, California’s cities continue to contaminate in discriminatory ways. A study conducted by Manuel Pastor and his colleagues demonstrated that racialized minorities are far more likely to live near active toxic release facilities that produce air pollution in the San Francisco Bay area (Figure 5.25).

Racialized minority, immigrant, and poor populations are not powerless in the face of environmental racism. Organizations such as Communities for a Better Environment work with local residents, such as those living in South Gate, to promote research, legal assistance, and activism. Environmental justice is the general term for the movement to redress environmental discrimination.

Environmental racism extends to the global scale. Industrial countries often dispose of their garbage, industrial waste, and other contaminants in poor countries. Industries headquartered in wealthy nations often outsource the dangerous and polluting phases of production to countries that do not have—or do not enforce—strict environmental legislation. Whether areas inhabited by poor, ethnic, or racialized minorities are deliberately targeted for unhealthy conditions, or whether they are simply the unfortunate recipients of the effects of larger detrimental processes, the connections among race, ethnicity, and the environment pose central questions for cultural geographers.

209