NATURE-CULTURE

6.4

LEARNING OBJECTIVE

Recognize the importance of the physical environment to political geography.

How people use the land and natural resources is profoundly influenced by politics. Whether a particular habitat is conserved or degraded often has much to do with the structures of a country’s land laws, tax codes, and agricultural policies. However, increasingly, politics is being defined by changing environmental conditions. National policies about environmental protection, guerrillas seeking a secure base for their operations, and the natural defense provided for an independent country by a surrounding sea—all reveal an intertwining of environment and politics. How governments respond to ecological crises like the loss of biodiversity, pollution, and climate change has become an important political issue. Let’s examine this complex two-way interaction between politics and the environment.

252

CHAIN OF EXPLANATION

When geographers Piers Blaikie and Harold Brookfield used the term political ecology, they were interested in trying to understand how political and economic forces affect people’s relationships to the land. They suggested that focusing on proximate or immediate causes—for example, the farmer dumping pesticides in a river or the poor peasant cutting a patch of tropical forest—provided an inadequate and misleading explanation of human-environment relations. As an alternative, they developed the idea of a “chain of explanation” as a method for identifying ultimate causes. The chain of explanation begins with the individual “land managers,” the people with direct responsibility for land-use decisions—the farmers, timber cutters, firewood gatherers, or livestock keepers. The chain of explanation then moves up in spatial scale, tracing the land managers’ economic, cultural, and political relationships from the local to the national and, ultimately, to the global scale.

One of the primary areas addressed by the chain-of-explanation approach is the character of the state, particularly the way in which national land laws, natural resource policies, tax codes, and credit policies influence land-use decision making. For example, if a state assesses high taxes on land improvements, such as terracing and channeling, its tax policies actually create disincentives for land managers to implement soil conservation measures. Conversely, if a state provides cheap loans to land managers to build such structures, its credit policies encourage soil conservation. There are many examples of state influences on individual land-use decisions, leading Blaikie and Brookfield to argue that one cannot fully explain the causes of environmental problems without analyzing the role of the state.

GEOPOLITICS

Spatial variations in politics and the spread of political phenomena are often linked to terrain, soils, climate, natural resources, and other aspects of the physical environment. The term geopolitics was originally coined to describe the influence of geography and the environment on political entities. Conversely, established political authority can be a powerful instrument of environmental modification, providing the framework for organized alteration of the landscape and for environmental protection.

geopolitics

The influence of habitat on political entities.

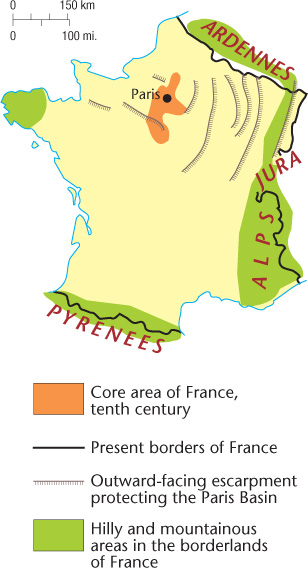

Before modern air and missile warfare, a country’s survival was often aided by some sort of natural protection, such as surrounding mountain ranges, deserts, or seas; bordering marshes or dense forests; or outward-facing escarpments. Political geographers named such natural strongholds folk fortresses. The folk fortress might shield an entire country or only its core area. In either case, it is a valuable asset. Surrounding seas have helped protect the British Isles from invasion for the past 900 years. In Egypt, desert wastelands to the east and west insulated the fertile, well-watered Nile Valley core. In the same way, Russia’s core area was shielded by dense forests, expansive marshes, bitter winters, and vast expanses of sparsely inhabited lands. France—centered on the plains of the Paris Basin and flanked by mountains and hills such as the Alps, Pyrenees, Ardennes, and Jura along its borders— provides another good example (Figure 6.23).

folk fortress

A stronghold area with natural defensive qualities, useful in the defense of a country against invaders.

Expanding countries often regard coastlines as the logical limits to their territorial growth, even if those areas belong to other peoples, as the drive across the United States from the East Coast to the Pacific Ocean in the first half of the nineteenth century has made clear. U.S. expansion was justified by the doctrine of manifest destiny, which was based on the belief that the Pacific shoreline offered the logical and predestined western border for the country. Underlying the doctrine was a racist ideology of Anglo-Saxon superiority, which held that Native Americans were savages blocking the progress of civilization and the productive use of the western lands. A similar doctrine led Russia to expand in the directions of the Mediterranean and Baltic seas and the Pacific and Indian oceans.

THE HEARTLAND THEORY

Discussions of environmental influence, manifest destiny, and Russian expansionism lead naturally to the heartland theory of Halford Mackinder. Propounded in the early twentieth century and based on environmental determinism, the heartland theory addresses the balance of power in the world and, in particular, the possibility of world conquest based on natural habitat advantage. It held that the Eurasian continent was the most likely base from which to launch a successful campaign for world conquest.

heartland theory

A 1904 proposal by Harold Mackinder that the key to world conquest lay in control of the interior of Eurasia.

253

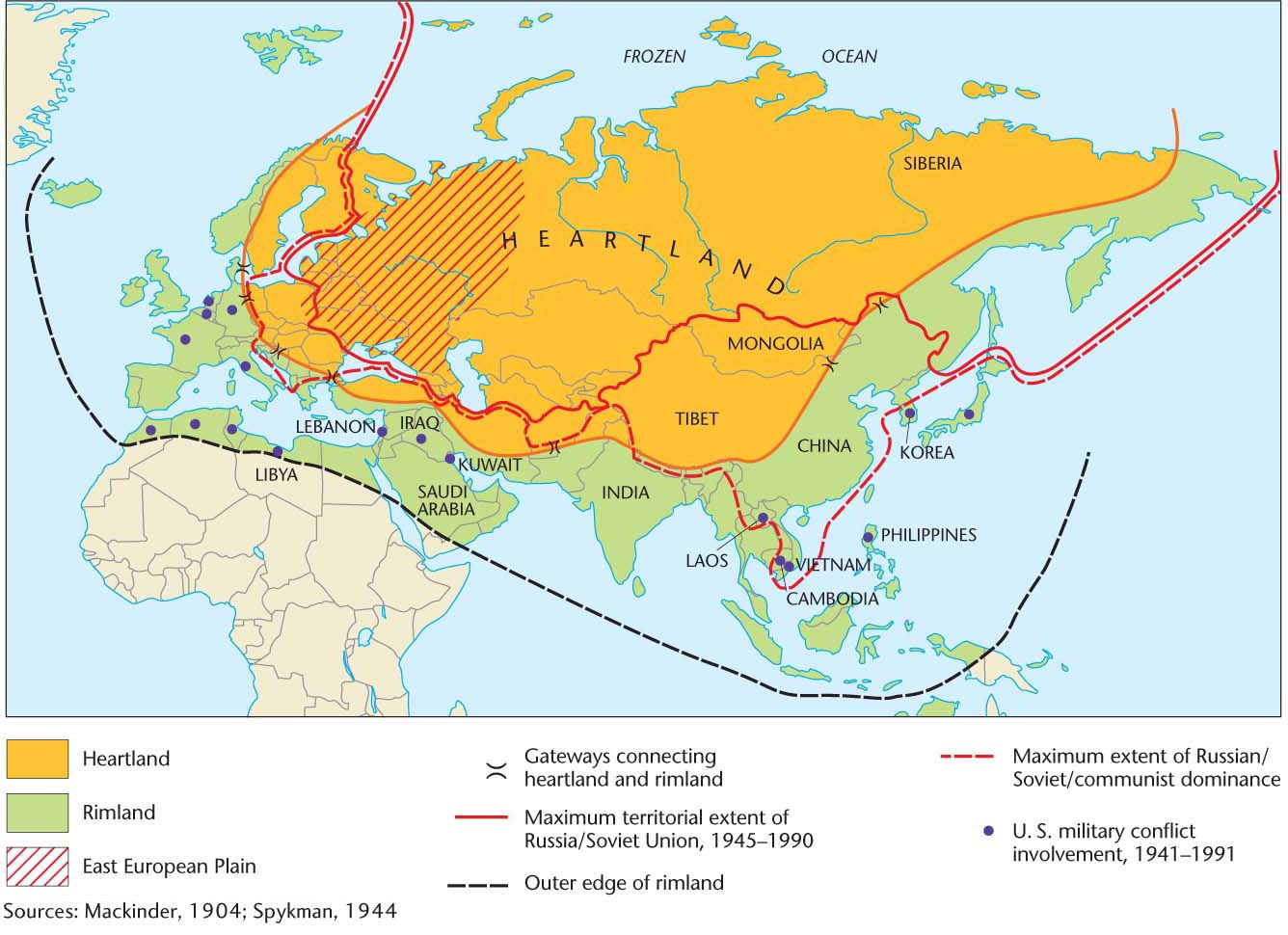

In examining this huge landmass, Mackinder discerned two environmental regions: the heartland, which lies remote from the ice-free seas, and the rimland, the densely populated coastal fringes of Eurasia in the east, south, and west (Figure 6.24). Far from the sea, the heartland was invulnerable to the naval power of rimland empires, but the cavalry and infantry of the heartland could spill out through diverse natural gateways and invade the rimland region. Mackinder thus reasoned that a unified heartland power could conquer the maritime countries with relative ease. He believed that the East European Plain would be the likely base for unification. As Russia had already unified this region at the time, Mackinder, in effect, predicted that the Russians would pursue world conquest.

heartland

The interior of a sizable landmass, removed from maritime connections; in particular, the interior of the Eurasian continent.

rimland

The maritime fringe of a country or continent; in particular, the western, southern, and eastern edges of the Eurasian continent.

Following Russia’s communist revolution in 1917, the leaders of rimland empires and the United States employed a policy of containment. This policy, in no small measure, found its origin in Mackinder’s theory and resulted in numerous wars to contain what was then considered a Russian-inspired conspiracy of communist expansion. Overlooked all the while were the fallacies of the heartland theory, particularly its reliance on the discredited doctrine of environmental determinism. In the end, Russia proved unable to hold together its own heartland empire, much less conquer the rimland and the world.

GEOPOLITICS TODAY

In the post-cold war period, geopolitics has reemerged as a dynamic field of political-geographic thought. As geographers Gerard Toal and John Agnew explain, the meaning of political geography is now reversed. Instead of focusing on the influence of geography and the environment on politics, “it now becomes the study of how geography is informed by politics.” By this they mean the ways in which political goals and ideologies, based on preconceived notions of cultural identities, regional stereotypes, and regional development hierarchies, influence the ordering of the world. How does the geopolitical outlook of a state structure the world into places of crisis or stability, regions of opportunity or danger, and states of allies or enemies? Many geographers distinguish this new focus on culture by labeling their approach “critical geopolitics.”

One of the important aspects of critical geopolitics is a concern with how geopolitics influences our understanding of human-environment relations and affects the way we transform the environment. Consider, for example, the current scientific and policy debates over global climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions. Worldwide debates must be placed in the historical geopolitical context of the global North’s political and economic domination of the global South. From the South’s perspective, according to Simon Dalby, “the North got rich by using fossil fuels for generations. Why should those in the South forgo the same possibilities just because they come on the development scene a little later?” According to advocates of the South, the North’s ideas about restricting future emissions of greenhouse gases globally will have a disadvantageous effect on the South’s economic development. Thus, questions of global environmental management are not restricted to the realm of science and technology; they also fall squarely in the realm of geopolitics.

254

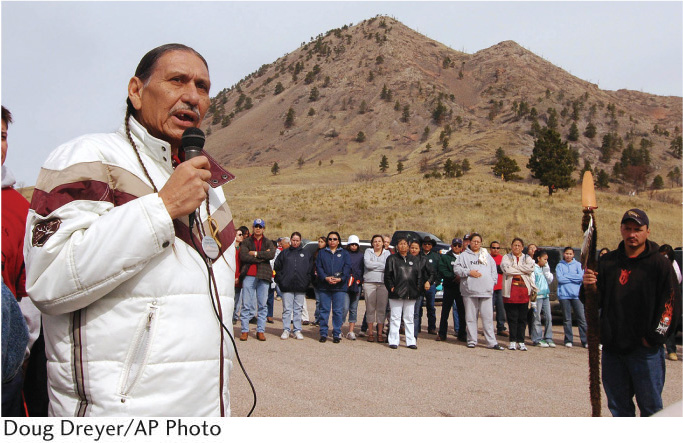

Another illustration of how geopolitics influences human-environment relations may be seen in the debates concerning the conservation of global biodiversity. Current global conservation policy suggests that the most effective way to save the world’s biodiversity is by creating protected areas such as national parks and reserves. However, Roderick Neumann has demonstrated that these protected areas, whether in the North or the South, were created in the historical context of European conquest and colonization. In the British Empire, protected areas were part of a grand economic development strategy to spatially reorder colonies into separate spheres of nature and culture. In the United States, park creation was conducted in the context of manifest destiny and the removal of Native Americans from their homelands and their placement on reservations. In both cases, the environmental management strategies of native cultures were denigrated as immoral and irrational, providing the justification for discarding local land and resource claims and practices. Today, those who have lost their land to protected areas argue bitterly that they bear the main costs of conservation (Figure 6.25). Thus, as with the case of global climate change, the North-South debates over strategies for the conservation of global biodiversity fall under the domain of geopolitics.

255

STATE MILITARIES AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Nearly every state has a military to defend its flag and territory. The ecological impact of all of these armies and navies is complex and sometimes surprising. Interstate warfare delivers perhaps the most spectacular and devastating effects. “Scorched earth” the systematic destruction of resources, has been a favored practice of retreating armies for millennia. During the Vietnam War, the U.S. military sprayed defoliants on that country’s tropical forests and croplands in an effort to deny the enemy of the cover of vegetation. Not only was vegetation destroyed, but the accompanying pollution is also blamed for 500,000 birth defects. In the 1991 Gulf War, the Iraqi military devised a scorched earth tactic of lighting over 600 oil wells on fire as it withdrew from Kuwait, thereby releasing tons of pollutants into the atmosphere and ground. People fleeing armies can have major environmental impacts. Wars create refugees and refugees tend to concentrate in encampments, sometimes comprising hundreds of thousands of people. For example, Kenya’s Dadaab camp and its immediate surroundings have been largely deforested as the growing population scavenges for fuel, wood, and building materials.

Even military exercises and tests can be devastating. Certain islands in the Pacific were rendered uninhabitable, perhaps forever, by American hydrogen bomb testing in the 1950s. The Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington State manufactured the plutonium for those bombs and many others (Figure 6.26). Now largely decommissioned, Hanford represents the single largest radioactive waste site in North America. Sited dangerously in the upper Colombia River drainage, the site’s radioactive contamination poses a long-term threat to both terrestrial and marine ecosystems over a vast territory. About a third of the underground tanks containing radioactive liquids are leaking into the soil and groundwater. It is hoped that the U.S. military and other agencies can clean up the site before contaminants enter the Colombia River drainage.

Militaries and wars have less visible and dramatic effects on the environment, some of which may actually be ecologically beneficial. During the civil war in Nicaragua, stretches of tropical forests became “no-person’s lands” as people did not enter out of fear of both the army and insurgents who used the forests as hideouts. As a result, wildlife populations recovered under the decreased hunting pressure. U.S. military bases have made vast areas off-limits to civilians and thereby inadvertently protected habitats for hundreds of endangered plant and animal species from commercial exploitation. When these bases are decommissioned (permanently closed), they are sometimes converted to conservation areas so that protection continues. For instance, part of the decommissioned Fort McClellen in Alabama became the 9,000-acre Mountain Longleaf Wildlife National Refuge in 2004, thereby continuing protection of one of the last remaining longleaf pine forests. Part of the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in San Francisco Bay was similarly passed to the San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge when it was decommissioned (Figure 6.27).

256

Clearly, warfare—especially modern high-tech warfare—can be environmentally catastrophic. Yet ecological destruction is not always the only result of war or preparation for war. As with many nature-culture phenomena, the interactions are complex and have unpredictable and unintended outcomes.